The working-class Belfast-born author trying to reinvent the post-Troubles novel

- Share via

On the Shelf

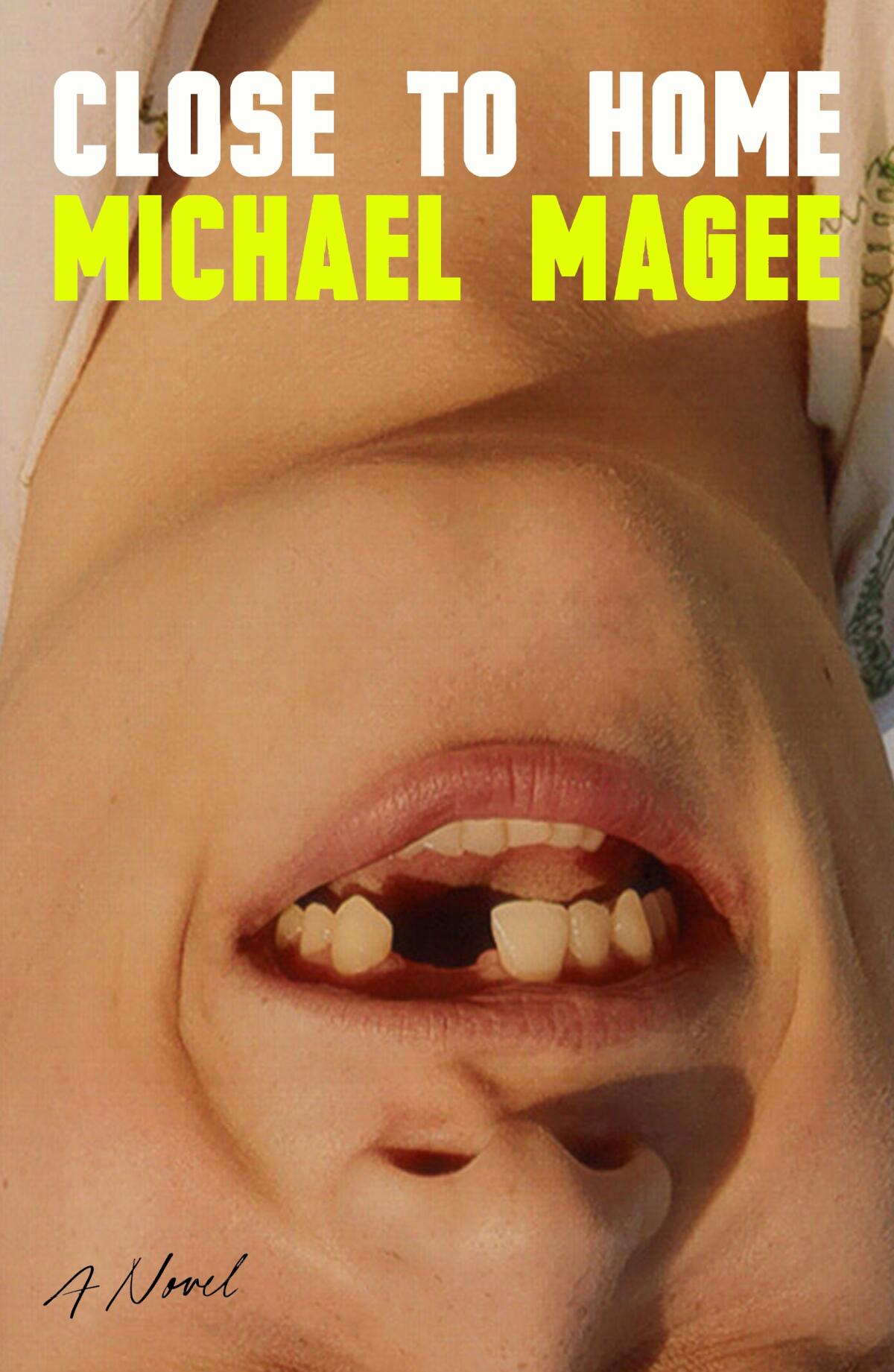

Close to Home

By Michael Magee

FSG: 288 pages, $28

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

Michael Magee was feeling lost.

He’d earned a degree in English in 2011, the peak of the global financial crisis. After “five years in the wilderness” he began pursuing his doctorate in creative writing at Queen’s College in Belfast. Magee soon discovered he came from an altogether different reality than the one his classmates knew — and he struggled to find his voice.

But after a night of drinking with a mentor from Dublin, he had an epiphany that resulted in his magnificent debut novel. “Close to Home” opens with a punch and follows its reckless protagonist through the aftermath of that violence, but unlike most Belfast novels it turns on inner conflict.

Paradoxically, that interiority opens up the external class divisions Magee faced in his life — and those that still mark Belfast today. “Close to Home” heralds a fresh and necessary new voice in Irish fiction. Magee spoke to the Times over the phone about his novel’s inspiration, Northern Ireland’s national PTSD and why he’ll take French autofiction over Belfast noir any day.

More than 20 years after the official end of Northern Ireland’s civil war, conflicts still simmer — and a potent, page-turning genre takes stock.

Let’s start with where you’re from.

I was born in West Belfast. I grew up in a housing estate in Poleglass on the very edges of West Belfast.

What were your models for writing a contemporary Belfast novel?

There are a few good Belfast novelists, but not a lot where I’m from. There are a lot of very good novelists like Glenn Patterson and Lucy Caldwell. I think Glenn Patterson’s early books, in particular, were quite good, because he was preoccupied with class. I guess that’s something I’ve sort of picked up on a lot of contemporary fiction is that money doesn’t seem to exist.

The novels that would have influenced me were American novels by writers like Denis Johnson and the French autofictional writers Annie Ernaux and Édouard Levé.

Why is it so challenging for American readers to find a Belfast novel that isn’t a crime story?

A lot of the novels that are written about Belfast or are set during the Troubles are almost like parodies. West Belfast is either written about as a ghetto or a no-go zone. So you get these characters that are caricatures of gangsters. They all have stupid accents and they’re all kind of burly guys who beat people up. It’s a very uncomplicated picture of what this place is. I was trying to write against that.

What was the genesis of “Close to Home”?

I’d published a few short stories and an essay or two, but nothing substantial. There was a weird inhibition hanging over me. I couldn’t open up in the way that I would have liked. I was so preoccupied with the idea of being published that the work kind of fell by the wayside. I think being in a hurry stymied me.

Then a friend of mine, Thomas Morris, came up for a visit. We sat up all night drinking and had that night where friendships are made. A couple of days later, he emailed me and suggested that I write a letter, and the stipulation was that I start at any point in my life, and just go from there. The letter had to be addressed to a person I respect and admire. So I did that. Of course, the letter became 20, 30, 40, 50, 60,000 words and by the end of a couple of months, I had this manuscript. It took me another five years then to mold it into a novel.

Yes, awarding the Nobel Prize in literature to Ernaux, a chronicler of illegal abortion, is a political move. But it’s also a victory for literature

Was the punch at the beginning something that emerged during the revising process?

It always opened with the punch. Those lines stayed the same throughout the process as I worked through what that punch meant, where it came from, and the conditions that led to it. A lot of it has to do with the intersection between violence, masculinity and the trauma that overhangs the generation of young people here.

Just as Sean has to navigate the repercussions of an act of violence he’s responsible for, “Close to Home” considers the Troubles from a place of trauma.

Yeah, absolutely. The thing is a lot of people suffered. There’s a lot of research now into mental health here. The proportion of the population that’s been affected by PTSD and trauma is massive. There is a reticence to talk about it but in my parents’ generation there was a feeling that they had to articulate what happened, what they lived through. This thing happened and they couldn’t rely on the education system or media to represent the truth. So there was a degree of political education happening in the domestic space.

But not everywhere?

I have friends who are the same age as me who have very little knowledge of what happened, which kind of baffles me because in the community that I grew up in it’s everywhere. It’s on the walls. You cannot not see it. For people in other parts of Belfast it’s not part of the fabric of the community.

Can you talk about Sean’s struggle in relation to your own?

I was the first person in my family to go to university. And so I had expectations about what education would give me and then it very suddenly dawned on me that I’m walking into an economy that didn’t have any use for me. The same thing happened to my mates. They were all tradesmen and suddenly they were all unemployed. That’s why the book is about that point in Sean’s life where he can go either way.

How close was this to your own experience?

I remember walking into Queen’s and everybody spoke differently than me, and everybody acted differently, had a different sense of humor, cultural references that went clean over my head. That’s how class works. You don’t really experience class until you move into a social space that isn’t the one that aligns with your background. Then you suddenly hear your voice. You hear how you talk. As the layers are peeled back, you start to realize that your moral barometer is different. I think that’s probably why the dropout rate for working-class people in prestigious universities is very high.

Northern Ireland wants to move forward. But 25 years after the Good Friday accord celebrated by Clinton and Biden, many are mired in a painful past.

Sean is constantly putting himself in positions where the specter of violence looms. Those moments are as fraught with tension and suspense as a caper.

He’s grown up in a world where the mode of resolving conflict is to resort to violence. But he’s also performing. He’s got these intrusive thoughts constantly going on in his head, these delusions of violence, that are very much a product of the world he was socialized in.

And yet it’s not the exterior conflict that drives “Close to Home,” but the war that Sean wages within himself.

Violence manifests itself in different ways in different contexts but underneath that there’s always a person. That’s not to say that there aren’t sociopaths in the world, but I always think that people are the product of external forces. Class, gender, race, or poverty don’t make a person, but it molds them.

Ruland’s new novel, “Make It Stop,” is now available.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.