- Share via

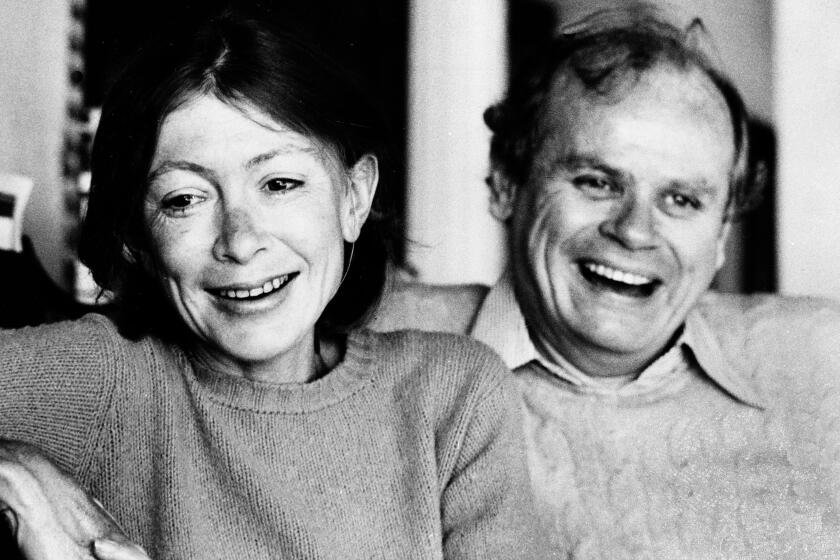

I came late, let me admit it, to the novels of Joan Didion. For too long, I considered them if not an afterthought then an ancillary line of work. Such a perception is hardly uncommon; the essays are what we think about when we think about Didion, and in more recent years, the triad of memoirs (“Where I Was From,” “The Year of Magical Thinking” and “Blue Nights”) with which she effectively concluded her career.

And yet, the novels. There is something about them, as well. “Play It as It Lays” was one of the most popular works of fiction selected by our “Ultimate Bookshelf” survey respondents. What this suggests is a certain kind of resonance, a recognition of who and where we are. This was the second of Didion’s five novels, which for more than 30 years she published pretty much in tandem with her nonfiction, alternating nearly book to book.

L.A.’s 16 essential works of literary fiction, from ‘The Day of the Locust’ to ‘If He Hollers Let Him Go,’ ‘Play it as it Lays’ to ‘Interior Chinatown.’

Her first, “Run River,” came out in 1963, when Didion was 28; it’s an unsentimental paean to the Sacramento of her childhood and adolescence, a river city defined by sprawling ranches soon to be subdivided, and a pioneer’s sense of something that might once have felt like manifest destiny. “You come from people who’ve wanted things and got them. Don’t forget it,” the protagonist, Lily Knight McClellan, hears more than once from her father. The statement marks the author’s heritage as well.

Didion, after all, was a fifth generation Californian; her great-great-great grandmother Nancy Hardin Cornwall left Arkansas in 1846. That history appears in “Where I Was From,” which four decades after “Run River” sought to rewrite the mythologies on which she’d been raised. “All that is constant about the California of my childhood,” she observes there, “is the rate at which it disappears.” It’s a theme that infuses not only the memoir but also the novel it means, in places, to deconstruct.

I’ve come to think that if “Where I Was From” had been Didion’s final book, it would have bestowed upon her career a marked circularity. Careers, though, don’t work that way. So it becomes the place where I begin to see the links between her fiction and nonfiction — in terms of theme, yes (that sense of living in a world that’s somehow fallen is a central motif throughout her oeuvre), but also in terms of execution.

“Play It as It Lays” appeared in 1970; the story of an actor, Maria Wyeth, who is in the process of decompensating, it is regarded as Didion’s “Hollywood” book. Certainly, it catalyzes key associations for her: the dislocation embodied not only by the character but also by the place. “In the first hot month of the fall,” Didion writes, “… Maria drove the freeway. … She drove it as a riverman runs a river, every day more attuned to its currents, its deceptions, and just as a riverman feels the pull of the rapids in the lull between sleeping and waking, so Maria lay at night in the still of Beverly Hills and saw the great signs soar overhead at seventy miles an hour, Normandie 1/4 Vermont 3/4 Harbor Fwy 1.”

This quality of drift has less to do with Hollywood than it does with Didion’s inner climate, the centrality in her work of atomization and narrative breakdown. The novel runs barely 200 pages but features almost 100 chapters. The fragmentation is a signature, a strategy Didion developed first in essays such as “Los Angeles Notebook” and “Slouching Towards Bethlehem,” which aspired not to closure but its opposite, a kind of jittery recognition that all stories collapse eventually — that we are always, in some essential fashion, working in the dark.

Your ultimate L.A. Bookhelf is here — a guide to the 110 essential L.A. books, plus essays, supporting quotes and a ranked list of the best of the best.

To an extent this has to do with Southern California, itself a fragmented landscape, in which, as she writes in her essay “Pacific Distances,” “a good part of any day … is spent driving, alone, through streets devoid of meaning to the driver, which is one reason the place exhilarates some people, and floods others with an amorphous unease.” At the same time, it was in her fiction that Didion first began to widen her perspective, to explore imperialism and the excesses of American power.

Her third novel, “A Book of Common Prayer,” published in 1977, takes place in the fictional Central American nation of Boca Grande; it presages the book-length nonfiction studies “Salvador” and “Miami.” Her fourth, “Democracy” (1984), comes framed as an early piece of autofiction; it is narrated by a character named Joan Didion. This is my favorite of her novels, a genre-blurring work about imperialism and politics, explored through the filter of a powerful Hawaiian family. It is also, like “Play It as It Lays” and “A Book of Common Prayer,” a book with a lost or troubled daughter at its heart. There’s a confluence here with Didion’s own history, particularly her daughter’s life and death. I don’t want to read too much into these books, which were composed over a number of years and are not (even “Democracy”) autobiographical, except to suggest that we are always writing from out of our experience, which means that the line between our fiction and nonfiction cannot help but bend.

Still, after the 1996 novel “The Last Thing He Wanted,” she seemed to disconnect from fiction. “I lost patience somewhat later with the conventions of the craft, with exposition, with transitions, with the development and revelation of ‘character,’” the narrator of that book insists. Eighteen years later, Didion would tell me she wasn’t sure if she had “the physical strength to undertake a novel.” She would say: “Nonfiction is more personal for me. It’s more personal in that it’s more direct.”

Joan Didion, who died Thursday, left a seismic impact on the literary world and her home state of California.

Even now, I can’t say I disagree with that assessment — when it comes to Didion, at any rate. But the fiction is more than an anomaly. In these five books, we see her working out the themes and structures that also animate her essays, the necessities and limitations of narrative, the utility of fragmentation, the complicated legacies of place. “Call me the author,” she writes in “Democracy.” And: “This is a hard story to tell.” Something similar might be said of all her writing, with its vision of a world where everything is conditional and we are always on our own.

Ulin, a former book critic and book editor of The Times, is the editor of the Library of America editions “Didion: The 1960 & 70s” and “Didion: The 1980s & 90s.”

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.