How free-market extremism became America’s default mode

- Share via

On the Shelf

The Big Myth: How American Business Taught Us to Loathe Government and Love the Free Market

By Naomi Oreskes and Erik M. Conway

Bloomsbury, 576 pages, $35

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

Ronald Reagan kicked off his presidency by declaring, “Government is not the solution to our problem; government is the problem.”

To many political junkies that seems like the dawn of a new antigovernment era. Economic wonks may look back further to Milton Friedman’s 1970 theory on maximizing shareholder wealth.

But Naomi Oreskes and Erik M. Conway go back even further in “The Big Myth: How American Business Taught Us to Loathe Government and Love the Free Market.” Everything from the anti-union attacks of the early 1900s to “Little House on the Prairie” comes under their purview as instruments in a concerted effort to shore up capitalism in its most extreme form.

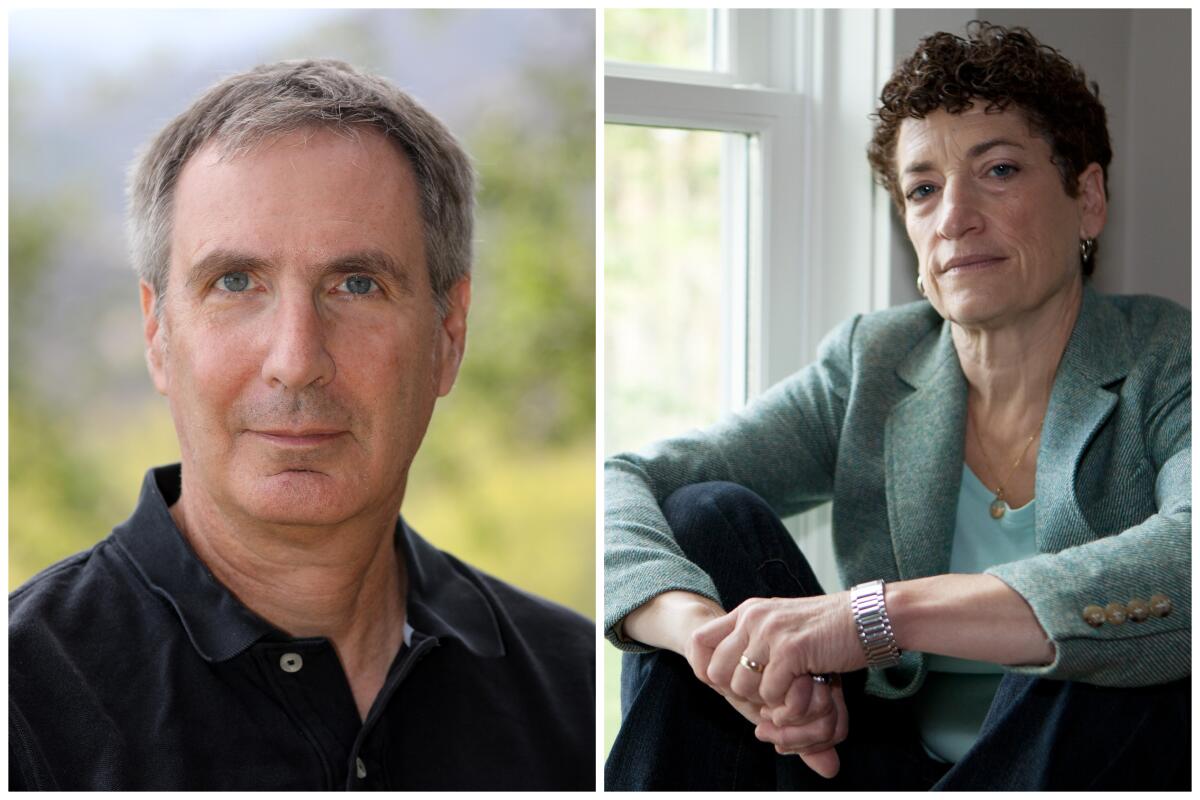

The book is a follow-up of sorts to the duo’s “Merchants of Doubt,” which pulled back the curtain on those who minimized the harms of tobacco, acid rain, climate change and much more. Conway, who works for Caltech and spoke on video from his home in Mammoth Lakes, is the more soft-spoken of the two. Oreskes, who was Zooming from Utah but teaches at Harvard, speaks faster, louder and with a sharper edge; she’s originally from New York.

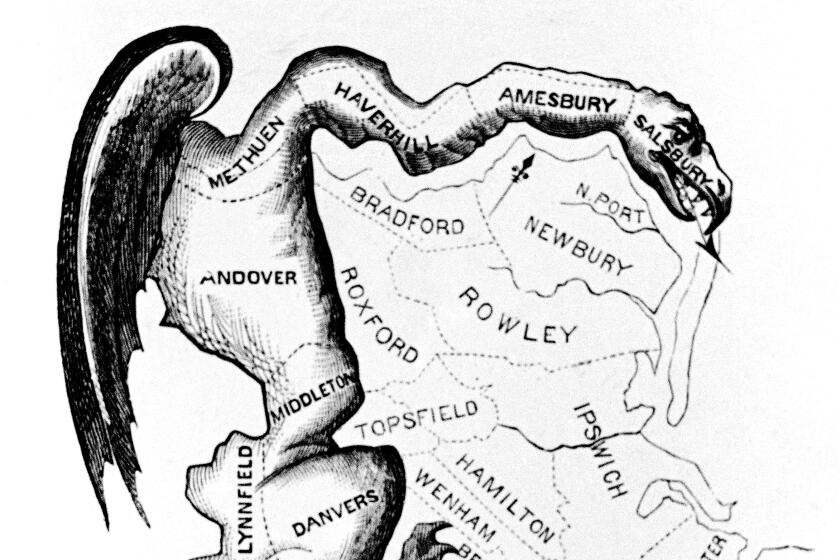

Nick Seabrook explains his new history, “One Person, One Vote,” and the way gerrymandering stymies everything from gun reform to democracy itself.

“The Big Myth” details how even as the New Deal improved millions of lives, economists, writers (like Ayn Rand), politicians and trade organizations committed to ideas aimed, as journalist John T. Flynn wrote, at building “power outside the parties so strong that the parties would be compelled to yield to its demands.”

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Market fundamentalism is an extreme idea that became mainstream. Is it possible to paint it as it really is or are we too late?

Oreskes: The point of the book is to show that these people take their point of view to an illogical extreme where they would defend child labor. Of course, there’s a spectrum of beliefs, but we’re trying to show how much of what is going on today with the Republican Party and Social Security — they would like to eliminate those programs — is part of a family of these activities.

You say you hope the book sparks conversations. Who is your target reader?

Oreskes: I hope people on the left read it. There’s a lesson for them too, that the solution is not always a giant federal program. The right wing has a point when they talk about overreach. I now believe that the best solution to any problem is the smallest solution that fixes it.

But that’s not our main target, which is people who consider themselves to be progressive but still say, “Markets, markets, markets.” The other audience for me is the guy sitting next to me on a plane when I get an upgrade to business class who says the market is going to solve climate change.

Do you think the Republicans’ MAGA turn has alienated some business leaders from the party, or is it still all about the bottom line?

Conway: There are a lot of companies that say progressive things and have progressive internal politics and yet still invest heavily in Republican politics. I don’t know how to square that circle.

Blue states fare better in most measurements of citizen success. We also give more of our tax dollars to red states, especially in the former Confederacy. Is it time for secession?

Conway: My ancestors fought for the Union, so I can’t go for that division. And the poor states would get poorer and the liberal in me doesn’t like the idea of that. I hope there’s a way to structure the laws to reduce what amounts to transfer payments of our tax dollars to them, but I don’t know what that is.

Oreskes: I have sometimes thought about a new version of states’ rights — we’d need a different term because that’s so loaded — for distributing power. It is nuts that the wealthy Democrat-led states give net money to states like Arkansas who just resent and hate us. One irony about climate change is that some states hit worst — Florida, Texas, Louisiana and Mississippi — have climate-denying leaders. But when a hurricane hits they’re at the trough demanding FEMA support.

What effect has Joe Biden had in changing the conversation?

Oreskes: Biden achieved a big breakthrough with the Inflation Reduction Act. What we have to say in our book is consistent with Biden’s moderate but FDR-ish Democratic positions — it’s not about destroying capitalism, it’s about fixing the problems the market can’t fix.

Daniel Akst discusses ‘War by Other Means,’ a portrait of four World War II pacifists, including Bayard Rustin and Dorothy Day, who changed American culture.

Conway: One thing I liked about Biden’s IRA is that it went about directing markets through subsidies, not taxes. We’re hearing that a lot of that money will go to states where the political culture is climate denialist, and that could start to change the conversation if the population comes to see it really benefits them. That can help reframe the narrative and undermine the arguments made by the trade groups and elite economists who talked about carbon trading systems that were too arcane for regular citizens to understand.

Biden’s State of the Union felt more combative in tone, arguing that the government is not the only solution but is always part of the solution. Does that kind of bully pulpit matter?

Oreskes: Liberals often think they don’t have to worry because the truth is on their side, but truth doesn’t speak for itself. You have to call out the lies and fight for truth. We’ve been bombarded with, “Government is inefficient and wasteful, there’s abuse, blah, blah, blah,” so it’s just ingrained in our culture.

Conway: Government can shape the direction of technology with its investments, but that’s the opposite of the story that people like to tell. Government investment in technology in the 20th century was enormous and enormously effective. The internet, jet engines and so forth benefited from government investment. The idea that everything the government does is bad is just ridiculous on its face. And most things the private sector invests in don’t work out.

Oreskes: There’s an incredible double standard about what we think about the private versus the public sector. Lots of businesses fail, but we don’t take that as a sign we should reject capitalism. Our book shows why that is and how it happens.

So the pro-regulation side needs to reframe its arguments and reclaim words like “freedom.”

Oreskes: The need to change the narrative about freedom is why, when I give talks about this topic, I wear my American flag pin. The right wing and free market forces have really manipulated the symbols of American freedom, as if free enterprise is somehow integral to American democracy. That’s an absolute fabrication, but they spent a lot of money and had talented people perpetuating the myth.

They’ve done tremendous damage by equating freedom with the right of anybody to do any effing thing they want. What about my freedom to not have to worry about what you or your company is dumping in my backyard, literally or metaphorically?

‘Uncertain Ground’ collects Marine and novelist Phil Klay’s essays on how we redefine citizenship and other fuzzy concepts as a nation forever at war.

Speaking of which, it feels like people are blaming the government more than big business for the East Palestine toxic chemical disaster.

Oreskes: I think this is a tragic example of what we call the high cost of the free market. There’s strong evidence that this tragedy could have been avoided with better government oversight, inspection and regulation. I understand there was a proposal to mandate electronic braking systems, which could have helped to prevent an accident like this. But there was a strong push against it from the industry, and not enough constituency pushing for it.

Is that the fault of the government or of the way society has, over decades, shifted its expectations of government and of big business?

Oreskes: Well, “the government” is us.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.