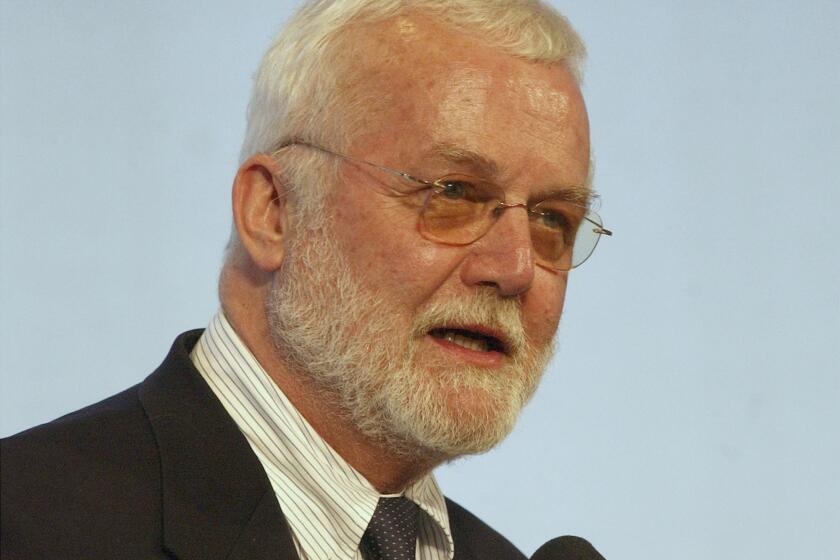

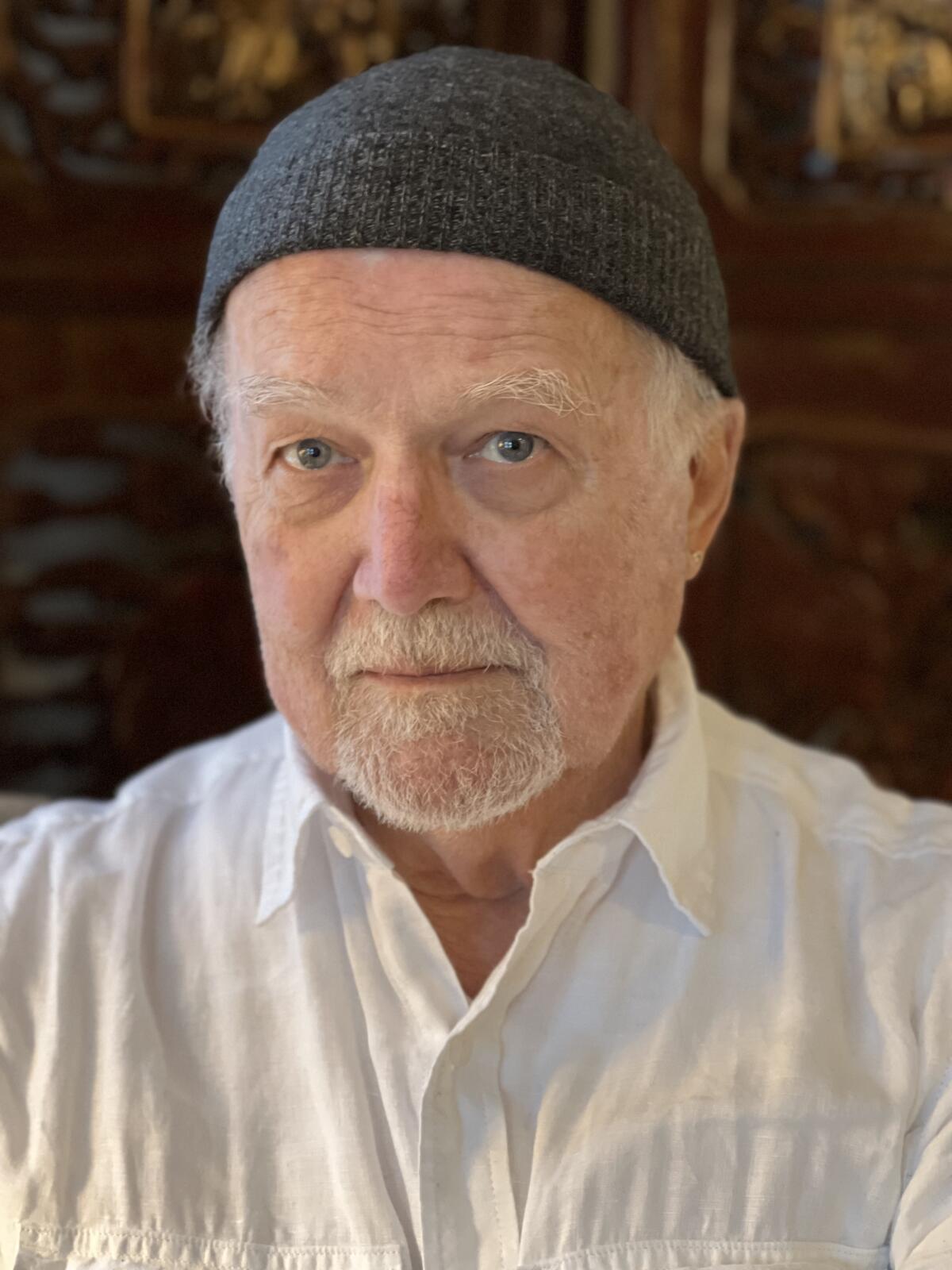

Appreciation: Russell Banks was a giant rooting for the underdogs

- Share via

Russell Banks, who died Saturday at age 82, gave me the best teaching advice I’ve ever received. This was in September 2011, at the Brooklyn Book Festival, where Banks was kicking off the tour for his 12th novel, “Lost Memory of Skin,” the story of a young man, known only as the Kid, adrift on the edges of a city that is Miami in everything but name. Like much of the writing that followed his 1980 novel “The Book of Jamaica,” “Lost Memory of Skin” blends a kind of gritty realism with allegorical and social concerns. Banks and I were chatting in the green room when he began to reminisce about a writing workshop he’d once taught at Columbia; its members included Rick Moody and Mona Simpson.

“Did you know how good they were?” I asked.

“Oh, yes,” he answered with a grin.

“What do you do when you have that kind of talent?”

“The only thing you can do,” he said, “is try to stay out of their way.”

That sense of generational engagement defined Banks’ approach to fiction, which was steeped in an awareness of himself as part of a heritage. “My life was changed by literature, almost more than anything else I can point to,” he told me in an interview for The Times. “It’s the guiding star for me. All I have is the entire body of the stories, of the poems, the plays, the literature that have existed for as long as human beings have been preserving their stories. So I can’t avoid it in my work.”

Russell Banks, who died Sunday at 82, circled similar themes across his many novels. For new readers and fans alike, here are the five most essential.

For Banks, an early gateway to this body of stories was Jack Kerouac, who, like him, was a product of working-class New England; Kerouac’s 1957 breakthrough, “On the Road,” came out when Banks was 17. Still, for all his attraction to the road novel — his own breakthrough, “Continental Drift” (1985), is built in part around a journey to Florida — Banks had more bracing ideas. These involved race and class and American mythologies, themes that continued to animate books, including the 1995 novel “Rule of the Bone,” which pays homage to “The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn,” and the prodigious “Cloudsplitter,” a fictionalized portrait of abolitionist John Brown that was a finalist for the 1999 Pulitzer Prize. Here, he was working the line of not just Twain but also Melville and Hawthorne: all those 19th century masters, Transcendentalist or otherwise.

If the road novel opened up, for Banks, an appreciation of the utility of movement, what interested him equally was what happened after one arrived. That, and — even more perhaps — the lives of those who never got to go, who were stuck or trapped by circumstances not of their choosing and yet sought not only to make do but also in some essential sense to persevere.

Let’s not pull our punches: This is heroism pure and simple, the heroism of those who despite their failings and the often numbing brutality of their situations, fight to raise children, hold down jobs, pay the bills, do what’s right. That it often doesn’t work out is part of the point or maybe the whole point. On some level, we never get to choose. Banks understood this in the blood; he was raised in rural New Hampshire, the son of an abusive alcoholic who beat him severely and left the family in 1952. “I hated my father, and I adored him,” the author told an interviewer in 1989; this tension centers the majority of his work.

I think of “Affliction” and “The Sweet Hereafter,” his most famous works because of the films that were adapted from them. I think of “Lost Memory of Skin,” with its nameless protagonist, 22 and a convicted sex offender — a kind of inverted sequel to “Rule of the Bone.” (What connected the books, Banks once said, was a shared recognition that “the structures and the bonds of society have broken down.”) More than anything, I think of his magnificent short stories, underrated only because of the acclaim bestowed, deservedly, on the novels: incisive miniatures steeped in longing, framed through the author’s ruthless and compassionate eye. In one of my favorites, “The Visit,” a man retraces the ghosts of his past, returning for one final time to the small town where his family came apart, not as an act of consolation but rather one of expiation.

This article was originally on a blog post platform and may be missing photos, graphics or links.

“I will not go back to the house in Tobyhanna,” the narrator insists, “or to the bar in town, just as — after having been there once — I have not returned to any of the other houses we lived in when I was growing up, or to the apartments and barrooms in Florida and Boston and New Hampshire, where I first learned the need to protect other people from myself, people who loved me, male and female. I go back to each, one time only, and I stand silently outside a window or a door, and I deliberately play back the horrible events that took place there. Then I move on.”

Banks’ character is not trying to hide what he has done, the sins that weigh on his soul. At the same time, what else is there for him to do but carry on? The complexity, the ambiguity, is reminiscent of Nelson Algren, an early mentor and another essential influence.

As it happens, Banks and I discussed Algren in 2009 during a centennial celebration for the author at Chicago’s Steppenwolf Theatre; the other participants included Barry Gifford and Don DeLillo. As we waited for the event to begin, the four of us, along with Algren’s publisher Dan Simon, found ourselves in another green room, going back and forth about Algren’s finest work. We were sitting in a circle on a pair of ratty couches. There was food: pizza, deli sandwiches. Was there beer, or am I just imagining that? If there wasn’t, there should have been.

“Never Come Morning,” “The Neon Wilderness,” “The Man With the Golden Arm,” a couple of others — we went through all of them. “How many writers are there,” Banks finally wondered, his face creased by an enormous smile, “about whom we could sit around and argue what’s their best book? With him, you have four or five.”

Prize-winning author known for ‘Continental Drift’ and ‘Cloudsplitter’ had just published his 14th novel, ‘The Magic Kingdom.’

Something similar might be said of Banks, who, like Algren, wrote in part to give voice to the marginalized. His oeuvre represents a record of silent battles, taking place out of sight, in homeless encampments and trailer homes and apartment living rooms, on job sites and in bars. The people here drink too much; they leave behind loved ones and must live on, with searing regret; they hit each other or restrain themselves from hitting each other; they experience yearning and despair.

“You can sense, I’m sure, my sympathies and my antipathies,” Banks told me in 2011. “It’s conventional sympathy for the underdog. Hell, what writer worth his or her salt doesn’t have sympathy for the underdog?”

Ulin is a former book editor and book critic of The Times.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.