Cormac McCarthy, 89, has a new novel — two, actually. And they’re almost perfect

- Share via

On the Shelf

Two New Novels by Cormac McCarthy

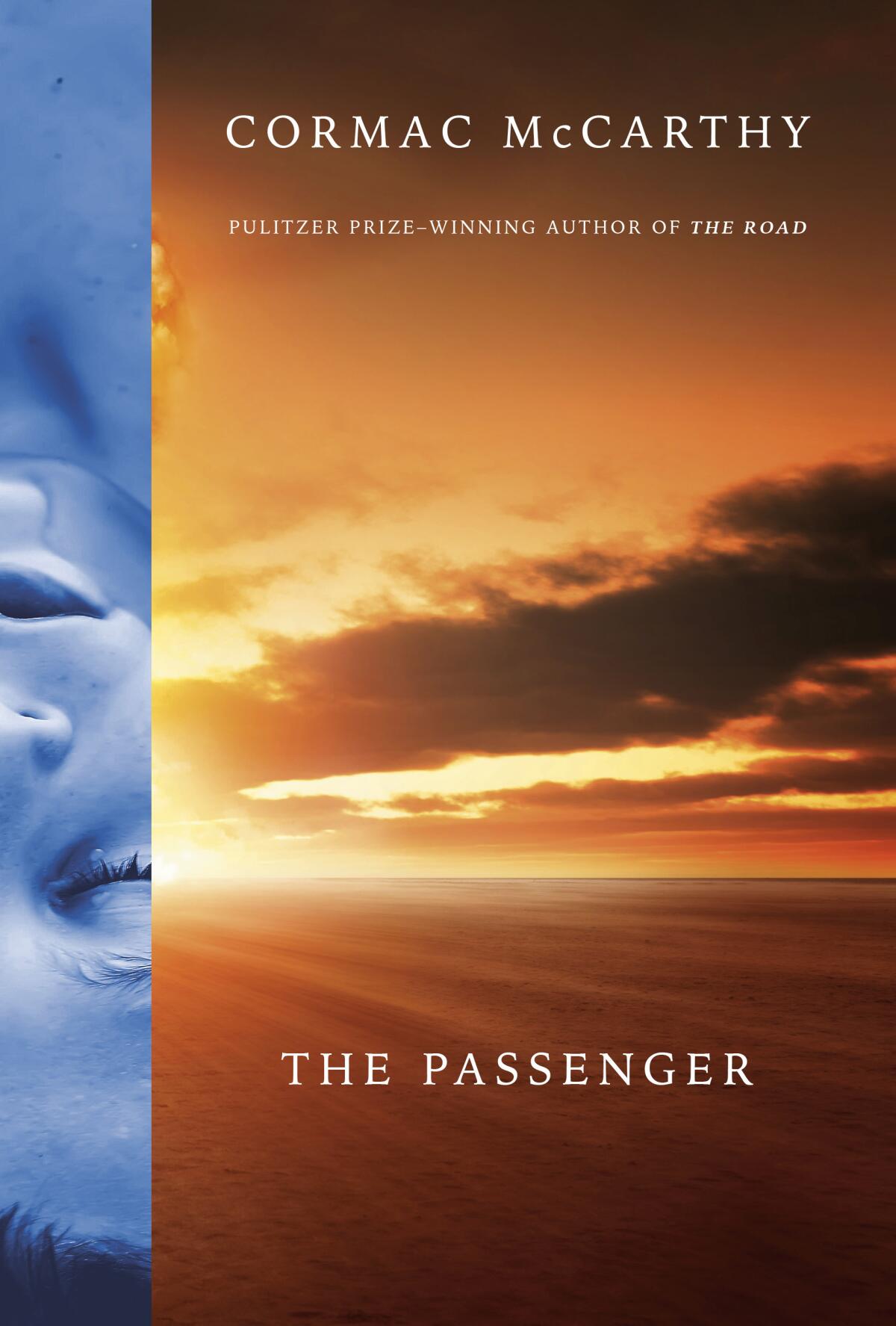

The Passenger

Knopf: 400 pages, $30

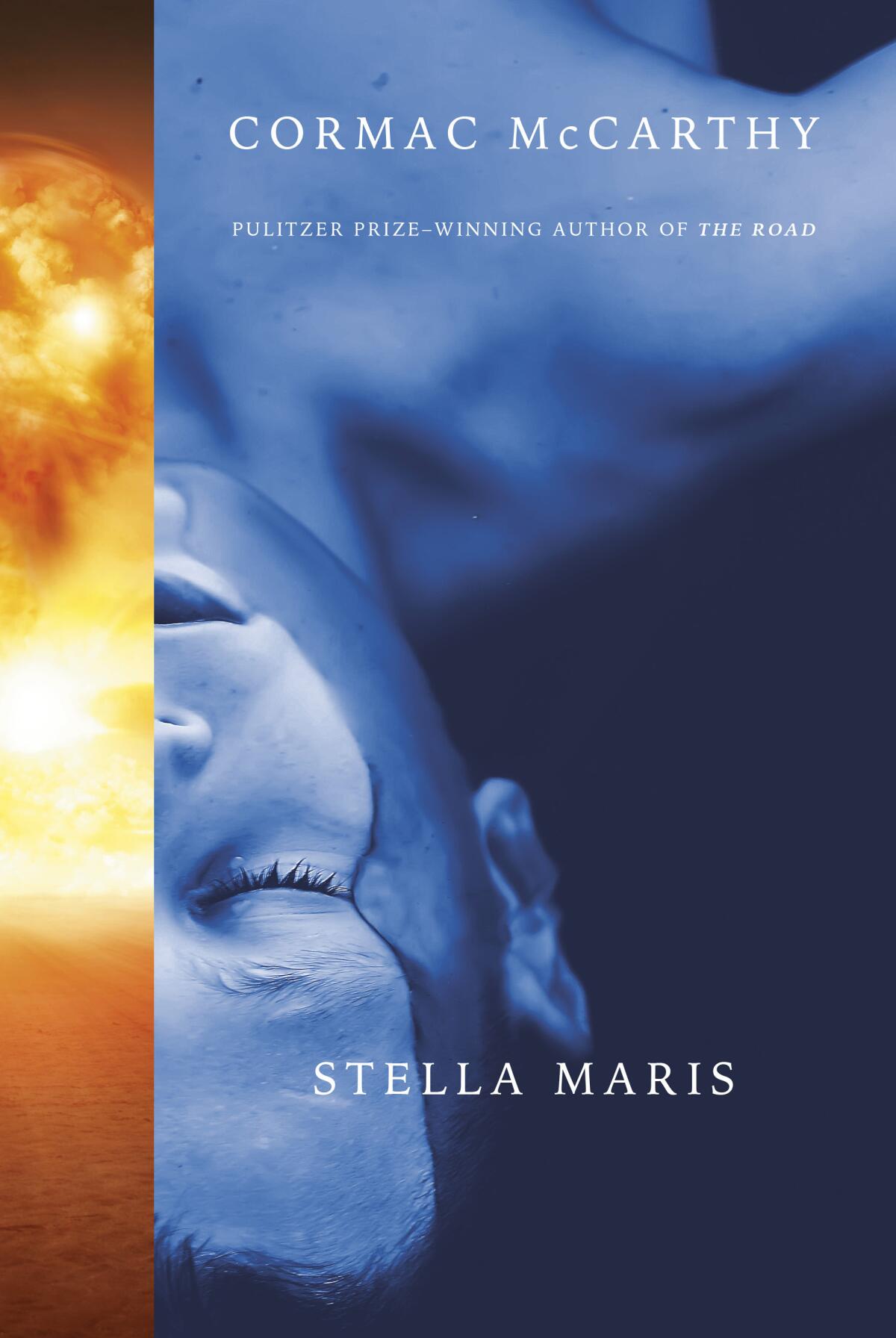

Stella Maris

Knopf: 208 pages, $26

(December 6)

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

Bobby Western is a salvage diver, a onetime physics graduate student who hangs out in dive bars with philosophically inclined roughnecks and thieves. It’s 1980 in New Orleans when Bobby’s quiet but perilous life takes a dangerous turn, sparking “The Passenger,” the new novel by Cormac McCarthy.

“The Passenger” is a brilliant book, a departure from McCarthy’s previous works that still feels of a piece. It’s set in the real world of the 20th century yet filled with the same elegiac language and drop-dead sentences of his antique “Border Trilogy” and the apocalyptic future of “The Road.” The latter book, his best-known, won the Pulitzer Prize, was made into a film and was selected by Oprah Winfrey for her book club in 2007, pulling the publicity-shy author into the spotlight. This is his first novel to be published since.

The story of a haunted man on the run, it has McCarthy’s classic linguistic flair, plus Thomas Pynchon’s wordplay and paranoia and, last but certainly not least, a sweeping history of theoretical physics. “The Passenger” is a stunning accomplishment: For McCarthy to publish a work of this scope and ambition at 89 is phenomenal. But it has a tragic flaw. Is it fatal?

One night, Bobby and his dive partner, Oiler, are sent to a small plane sunk deep in the Gulf and discover that the black box is missing. So is one of the passengers; the rest are, eerily, strapped in their submerged seats. When the crashed plane and its dead occupants fail to make the news, Bobby begins to worry they’ve seen something they shouldn’t have. He’s mildly interested in finding out about the missing passenger, but mostly he tries to lay low.

Cormac McCarthy’s rugged road to respectability

Bobby moves into a rented room above a local bar that has seen a string of occupants meet untimely ends. Bobby doesn’t mind — handsome, intelligent and possessing a secret stash of dough, he appears to move above the concerns of his barfly cohort. Or maybe he likes to court danger: Before he came to New Orleans, he was a Formula Two race car driver. He rarely reveals what’s on his mind.

It takes his friend “Long John” Sheddan to tell us plainly: “He’s in love with his sister.” This is no spoiler; it’s only 30 pages in, and Sheddan lays it bare — a slightly mythologized version of the siblings’ relationship that hangs over the rest of this novel and also “Stella Maris,” McCarthy’s companion novel, a sort of coda that will be released Dec. 6. That volume consists solely of conversations between Bobby’s sister and her psychiatrist in a mental institution. She is introduced first in “The Passenger.” She’s the corpse on the first page, sometimes called Alice and sometimes Alicia, and she occupies alternating, italicized chapters.

Alicia is searingly brilliant at mathematics, ethereally beautiful and usually in conversation with a troupe of third-rate vaudevillian hallucinations. Alicia is obsessed with death and her older brother, as in love with him as he has been with her since she was an adolescent. She’s so smart that her discussion of theoretical math drives Bobby to drop it for physics, yet her romantic obsession with him drives her to suicide.

And we’ve gotten to the flaw. Perhaps it will not bother you as it bothers me. Must the core of this book be a love story between an older brother and his younger sister? Couldn’t a writer with McCarthy’s capacious imagination conceive of an adult, independent woman who could serve as an equally powerful lost love? I realize he’s been here before — his 1968 novel “Outer Dark” was about brother-sister incest — and of course any novelist can put anything he or she likes into fiction. But it is 2022. An older brother in love with his younger sister? It’s not tragic; it’s creepy.

In our latest quarantine diary, the author of ‘These Women’ digs ‘Blood Meridian’ but can’t get enough of Laura Ingalls Wilder.

If we can ignore that for a moment — and take a look at the cover, maybe you can’t — the book follows Bobby around New Orleans, eating and drinking at still-standing classics including Tujague’s and the Old Absinthe House. He willfully ignores signals that something is wrong. A colleague dies in an underwater accident. His room is ransacked and his cat disappears. Two FBI-ish guys show up looking for him frequently — so frequently that they might instead be from the mafia or some more mysterious outfit.

McCarthy turns his substantial writerly gifts upon two distinct forces: the mechanical and the theoretical. He attends to the exquisite detail of Bobby’s physical world — the sounds and feel of an oil rig in a storm, the touch and clunk of a cigarette machine in a bar, the step-by-step process of removing a bathroom cabinet or digging up and carting off buried treasure. All the while, Bobby converses with friends who riff on time or men and women or Vietnam or failure, paragraphs and pages of disquisitions that can be funny and moving and dirty and insightful. Sometimes it feels a little like being trapped in a dorm hallway at 1 a.m. with a smart sophomore who is really, really stoned.

“You said once that a moment in time was a contradiction since there could be no moveless thing. That time could not be constricted into a brevity that contradicts its own definition,” Long John tells Bobby. “You also suggested that time might be incremental rather than linear. That the notion of the endlessly divisible in the world was attended by certain problems. While a discrete world on the other hand must raise the question as to what it is that connects it.” There are oodles of passages like this, so much to puzzle over for those who like to puzzle hard while reading their fiction.

As someone who hasn’t studied any higher math or physics, I didn’t always find a foothold in the theoretical arguments here. (I came closer to understanding this kind of math while reading Karen Olsson’s “The Weil Conjectures,” 2019.) In “The Passenger,” theoretical physics frequently comes across as a series of handoffs from one scientist to another, with entertainingly framed biographies about who proved the last guy wrong.

Let’s make this a whole lot easier.

Many of the discussions of math and physics come from Alicia’s sections, both in “The Passenger” and “Stella Maris.” Her conversations with vaudeville hallucinations are unfortunately retro — the main guy, the Thalidomide Kid, has his disabilities played for laughs; two characters dress up as blackface minstrels. The Kid — a name McCarthy also used for his protagonist in 1985’s “Blood Meridian” — began appearing to Alice during adolescence and serves as a hectoring protector. His patter is full of malapropisms and wordplay (“we got lights and chimeras”) and his turn from annoying and obnoxious to ultimately sympathetic points again to McCarthy’s copious talent.

We see Alicia and Bobby each go to visit their beloved grandmother in Tennessee, asynchronously. Their father, a scientist, worked on the Manhattan Project and met their mother, a local Tennessee beauty, when she was working at the Y-12 electromagnetic separation plant that produced enriched uranium for the first atom bombs. The marriage didn’t last. And if you’re wondering if the sins of the father are being visited upon the Western siblings, you’re getting warm.

Bobby and Alicia’s narratives move side by side in a doomed spiral. Alicia is dead on Page 1, and Bobby’s choices narrow around him almost before he can save himself. He’s pushed from the comfort of New Orleans to a near-feral existence on the road — a journey rendered in prose that can’t be equaled. “In the morning he sat with his feet crossed under him and watched the sun rise. It sat swagged and red in the smoke like a matrix of molten iron swung wobbling up out of a furnace.” It’s Cormac McCarthy writing as only Cormac McCarthy can.

With its cast of ruffians, its American sins, its contemplation of quantum physics, its low life and high ideas, “The Passenger” is almost a perfect book. If only.

BEFORE a morgue culture determined to hang a tag on every toe, Cormac McCarthy stands defiantly alive and untagged.

Kellogg is a former books editor of The Times. She can be found on Twitter @paperhaus.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.