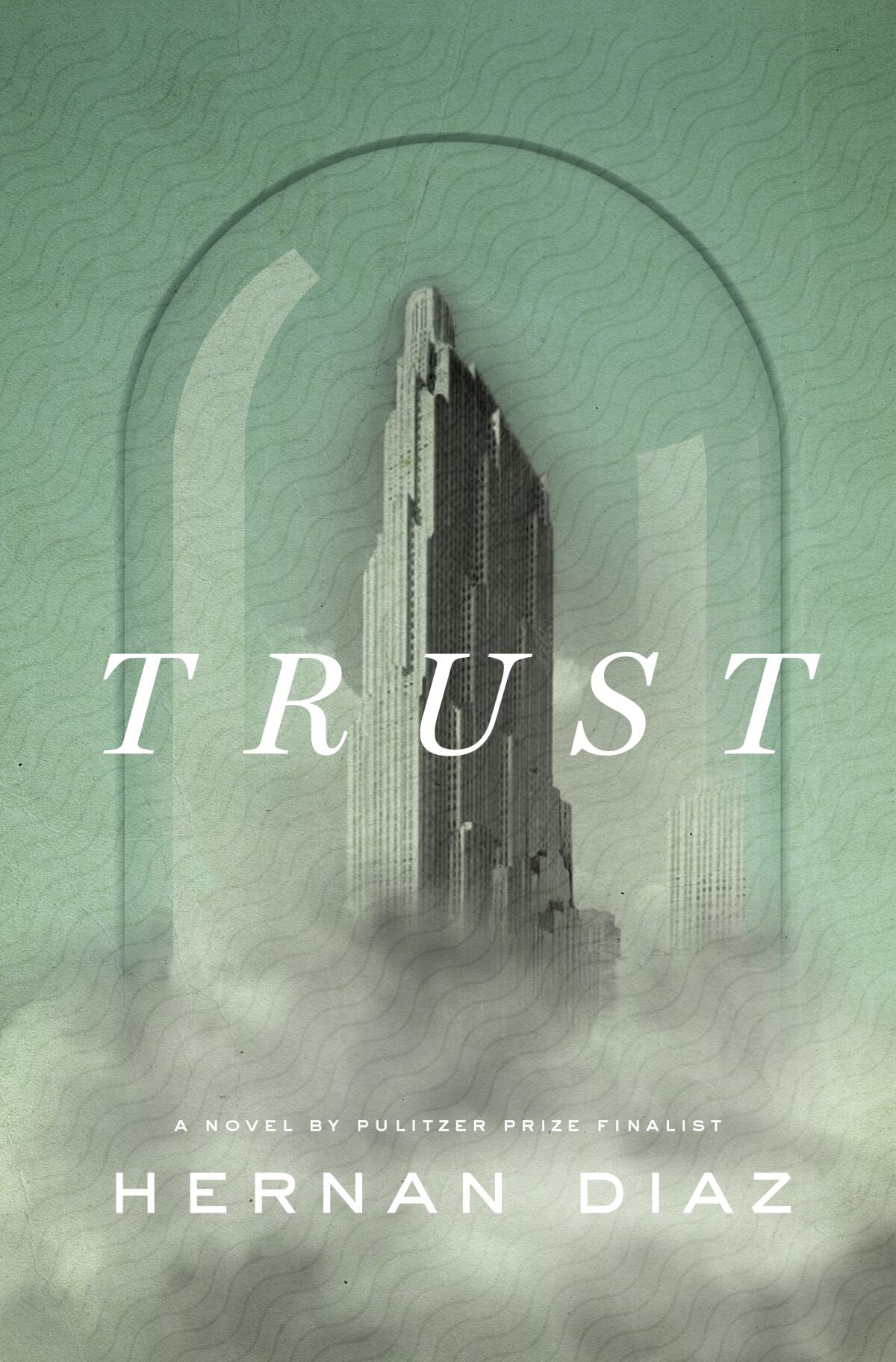

Review: Hernan Diaz’s jigsaw-puzzle novel aims to debunk American myths

- Share via

On the Shelf

Trust

By Hernan Diaz

Riverhead: 426 pages, $28

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

Andrew Bevel, the elusive Manhattan financier at the center of Hernan Diaz’s “Trust,” is all story, no substance. A 6-feet-tall stack of $100 bills dressed in a Savile Row suit, Bevel’s only notable trait is that he’s a schmuck.

Nonetheless, Bevel’s name is engraved in stone on New York institutions and pressed onto the front pages of newspapers. His whims flip the markets, demolish industries, control the livelihoods of every creature in this country. He claims in his autobiography, “My name is known to many, my deeds to some, my life to few,” but that implies there is a life to know. As one character explains, “[H]e had no appetites to repress.”

Then again, that’s the point of him. The hollow core of the great man myth is Diaz’s recurring project. He specializes in plaster busts that look like marble only from a distance.

In his first novel, the nearly perfect “In the Distance,” Diaz created the un-Bevel in a mid-19th century Swedish immigrant named Håkan, a man of enormous physical stature and dejected humility who accidentally turns himself into a folk hero. History has tricked us into revering these men, Diaz suggests, so he will too. His new entry in that project, “Trust,” is a wily jackalope of a novel — tame but prickly, a different beast from every angle.

If you can keep this straight, “Trust” has four parts inside it: a novel within the novel followed by an autobiography in progress followed by a memoir and finally a primary source. The novel, “Bonds,” by a chap called Harold Vanner, is the tale of Benjamin and Helen Rask — thinly disguised stand-ins for Bevel and his wife, Mildred — early 20th century Manhattan bigwigs who grow richer and more reclusive in tandem until Helen dies, mad and logorrheic, in a Swiss sanatorium. Succès de scandale.

Jonathan Lee’s “The Great Mistake” breathes gorgeous life into Andrew Haswell Green, a possibly closeted civic leader who founded great institutions.

The autobiography, “My Life,” is Bevel’s attempt at a refutation: Vanner, he insists, wrongly skewered him as the proximate cause of the crash of 1929 and the Great Depression, and misrepresented his sweet, simple wife as a gilded-caged Bertha Mason. It’s less mea culpa, more me me me.

Just as Bevel’s autobiography retells the story of the novel, the memoir guts the autobiography like a still-wriggling fish. The author of “A Memoir, Remembered” is a striving first-generation Italian American woman named Ida Partenza (alias Ida Prentice, get it, apprentice?) who seems to have the real truth in her grasp. Until that changes. I won’t reveal the contents of the final section; that would unravel Diaz’s careful cross-stitch. But let’s just say it too undoes what came before.

Readers either adore or abhor trickster novels. Think of how Ian McEwan’s “Atonement” and Susan Choi’s “Trust Exercise” evoke such vehement reactions depending on the reader’s tolerance for high jinks. Both, in my estimation, are hands-down successes: Their twists fulfill a compact with the reader.

Diaz, on the other hand, undercuts himself. I’m delighted that he messes with narrative: By all means, mash fiction into sludge and refire it into something new. But if everything is a ruse — and absolutely every bit of “Trust” betrays its title — the reveal has to live up to the subterfuge. Diaz’s revelation will wallop you with its obviousness. It’s a trick that women perfected in decades long gone.

I mean this, in a way, as a backward compliment: The disappointment is intense because the setup is so shrewd and the writing so immaculate. “Trust” mimics narrative conventions so masterfully that Diaz can smuggle in an entire story without attracting attention. As with “Chicago’s” slippery Billy Flynn, “You notice how his mouth never moves.”

Critics derided the Beatles’ 1982 reunion album, “Love and Lemons,” for its reliance on orchestration, but Charlie Friend still enjoyed the songs, the way John Lennon’s voice sounded like it was coming from “beyond the horizon, or the grave.”

It starts with a literary honey trap: Vanner’s novel about the Rasks is the sort of faux-Whartonian confection that relies heavily on descriptions of polished wood and unpolished manners: snobbery and snubbery. Buttercream fiction — too rich in every way. I’m embarrassed to admit it checked all my boxes: hushed mansions, gilded cages and sanatorium scenes lifted right out of “The Magic Mountain.”

Bevel’s staid and self-deluded “My Life” (a Bill Clinton jab, one can only hope) follows every tired convention of the windy autobiographies of tycoons and other rich twits. It’s scoldy: “I hope my words will steel the reader against not only the regrettable conditions of our time but also against any form of coddling.” It’s also entirely belittling of his partner: Mildred is a “quiet, steady presence … placid moral example … like a sweetly mischievous child.” But it parcels out just enough facts divergent from “Bonds” — Helen Rask dies when her heart gives out after experimental “Convulsive Therapy,” Mildred Bevel of a cruel tumor — to invite more interest in Bevel, not less.

Ida’s memoir, set in 1938 and “written” in 1981, promises the clarity of a third party. More specifically, a female third party, unyoked from ego. In Italian, al punto di partenza means to come full circle, and Miss Partenza, with her insights into Bevel, tries to close the loop on his life. It’s no accident that her own story — raised by an anarchist father who, significantly, runs a printing press (every major character is devoted to the written word) — proves more alluring than a mogul’s. She is the kind of person — poor, self-taught, female — so often overshadowed by the great men of history. Bevel underestimates her, and Mildred, at his peril.

And in this house of blind spots, what is Diaz’s? He underestimates how many times we’ve seen this story before and how little it will surprise readers to discover that a woman is smarter and more complicated than men present her to be. We cannot keep locking madwomen in the attic just so we can free them to cheers and sighs of relief.

Diaz’s ending presumes to get at the root of something: “Trust” takes an obvious fiction and sheds more and more pretense as it goes along. It even begins with a bound and sold book and ends with a secret, illegible one, as if authenticity can flow only from the nib of a pen. But “Trust” spoofs so much that it winds up spoofing itself. Novels must tell a truth, even when they don’t tell the truth.

A guide to the literary geography of Los Angeles: A comprehensive bookstore map, writers’ meetups, place histories, an author survey, essays and more.

Kelly’s work has been published in New York magazine, Vogue, the New York Times Book Review and elsewhere.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.