Review: The traumas of history blur into the present in a time-bending Korean graphic novel

- Share via

On the Shelf

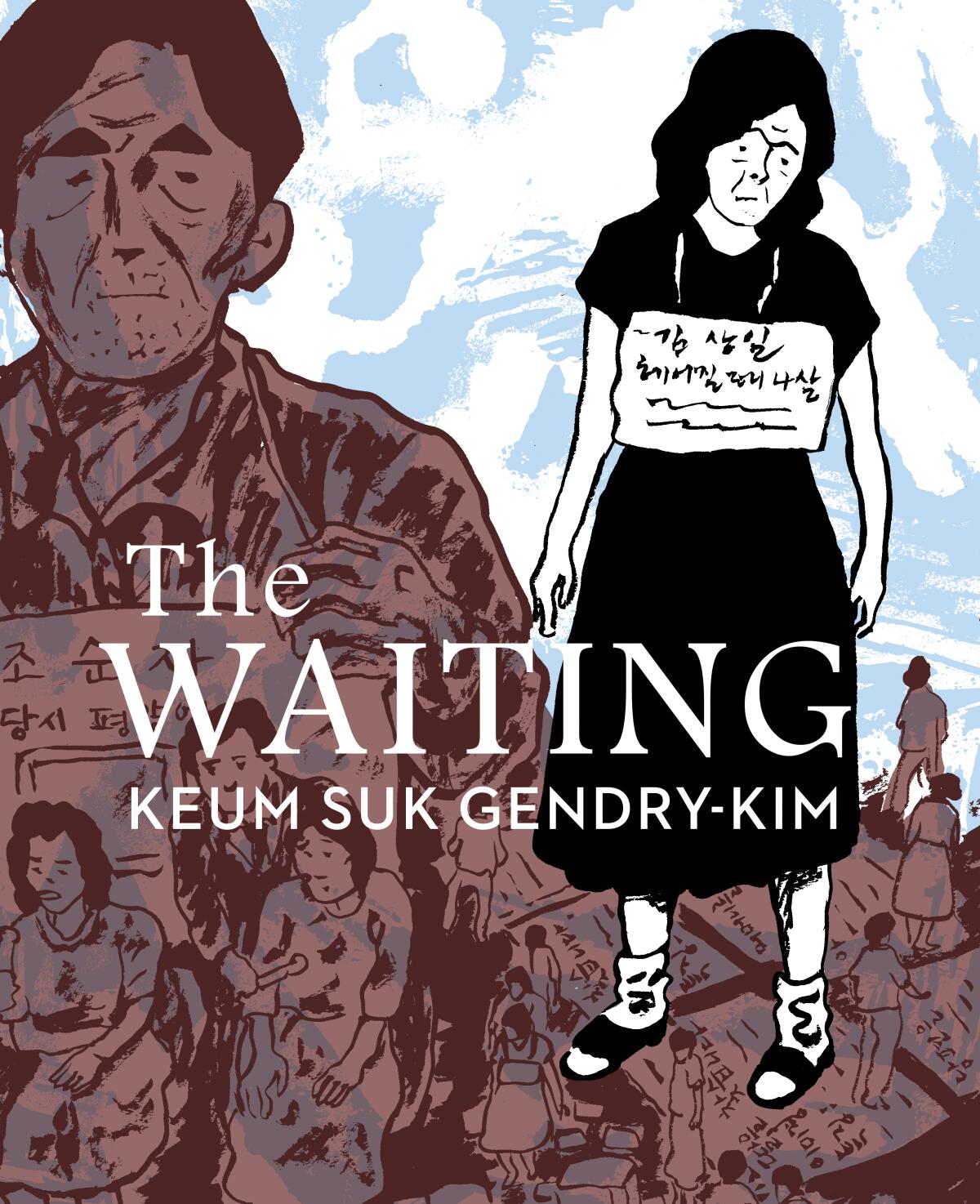

The Waiting

By Keum Suk Gendry-Kim

Translated by Janet Hong

Drawn & Quarterly: 248 pages, $25

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

The term “graphic novel” has long been a catch-all, a way to describe any long-form comic. That’s not without a certain logic in a form where even a “true story” comes filtered through the eye of its creator, in images as well as words.

I think of Art Spiegelman’s “Maus,” which recounts the Holocaust; the Jews are portrayed as mice and the Nazis as cats. Or the graphic war reportage of Joe Sacco, which juxtaposes portraiture against wide-frame panoramas to evoke the effects of armed conflict through both a personal and collective lens. In each, we are in the realm of the interpretive — neither documentary, exactly, nor fiction. This is the inherent tension of a style of storytelling that develops via sequential drawings.

Keum Suk Gendry-Kim’s second book, “The Waiting,” offers a compelling case in point; it’s vividly rendered graphic fiction with roots in autobiography. The story of a South Korean mother and daughter unfolds in present-day Seoul and in the crucible of memory. The mother, Gwija, has lived through decades of upheaval, beginning in the era of Japanese colonial rule and continuing through the Korean War. Her daughter, Jina, is an artist and a writer who, as the novel begins, has been told she must leave the rental apartment she calls home.

“I loved the city,” Jina tells us, over a panel that portrays a cozy streetscape. “I didn’t want to leave. I liked having a café, diner, supermarket, and laundromat outside my door.” Hers is the kind of longing any one of us might know. The problem — all too common in Seoul, as elsewhere — is that although some of Jina’s writing has been successful, “even at this age, I still don’t own a home.” In that sense, she is representative of the contemporary creative class: an accomplished practitioner reckoning with the economic instability that so often comes with a life in the arts.

Not only that: She has her aging mother to think about.

The graphic memoirist spirals back through his life in ‘The Loneliness of the Long-Distance Cartoonist,’ in tune with a culture in quarantine.

Gwija, however, doesn’t believe she needs looking after; in her mind, it is the other way around. “My youngest lives right around that corner,” she tells a neighbor. “She likes lettuce kimchi, so I was going to drop some off.”

The exchange offers a subtle glimpse of the mother-daughter relationship as symbiotic more than dutiful. It is also complicated by an unfulfillable promise Jina once made to her mother: to “find her oldest son.”

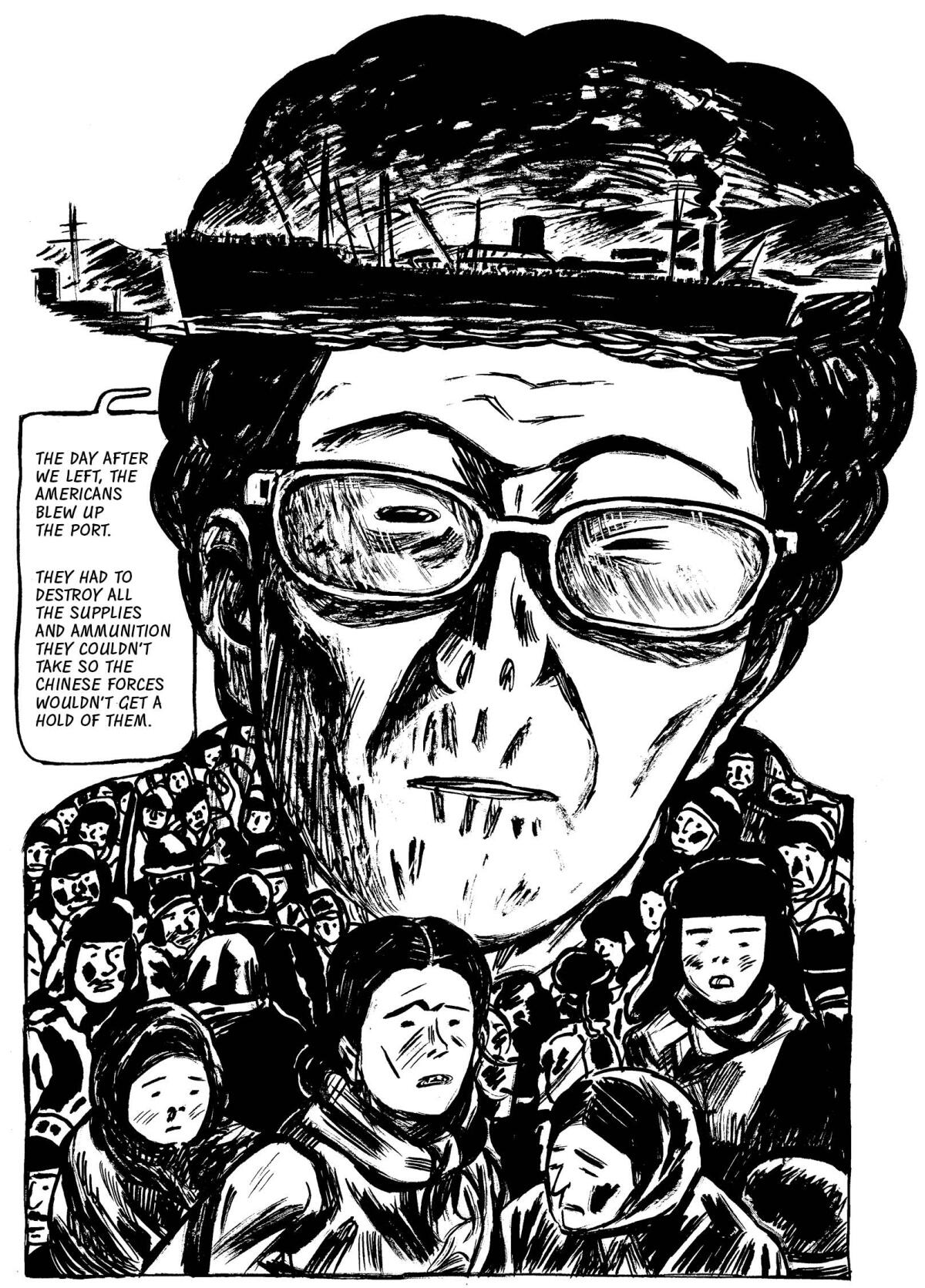

As “The Waiting” progresses, we learn that this may be impossible; Gwija was separated from her young son, Sang-Il, and her first husband as they fled south from communist forces in 1950 at the onset of the war. The circumstance echoes that of Gendry-Kim’s mother, who lost touch with her older sister at the same time.

“I had no idea she’d lived in Pyongyang, North Korea,” Gendry-Kim writes of her mother in an afterword. “When the Korean War broke out, her sister was the only one who hadn’t been able to get on the train evacuating south.”

As for the decision to recast the story, she writes, “I chose to create this work as fiction, rather than nonfiction because I didn’t want to hurt those who shared their stories so vulnerably with me.”

Gendry-Kim is referring not only to her mother but also to two elders she interviewed about reconnecting with relatives at mass family reunions organized by North and South Korea. Her sources feared government retaliation against their loved ones in the North. At the same time, she is also addressing something bigger: the issue of cultural memory.

“The generation that experienced the Korean War is dying,” she explains, “and with them, the painful memories are disappearing too. The current generation has little interest in the reunifications of the two Koreas. They dismiss the pain of separated families, since for them the Korean War is too far in the past.”

Five authors of Korean thrillers you should be reading: You-Jeong Jeong, Un-Su Kim, Young-Ha Kim, J.M. Lee and Hye-Young Pyun

“The Waiting,” then, is graphic novel as reclamation project, an attempt to preserve before it is too late not a documentary history so much as an emotional one.

At the heart of the process is Gwija, who subtly but forcefully becomes the center of the book. Her experience as a refugee operates as a spine of sorts for what turns out to be a pair of interwoven narratives: the story of Gwija’s separation from her northern family and the chronicle of her relationship with Jina in the present day. It’s a deft move because one cannot exist without the other. Had Gwija not been displaced from her son and first husband, Jina never would have been born. The situation recalls Han Kang’s 2016 novel “The White Book,” in which a woman reflects on the older sister who died during childbirth — and in so doing cleared a space in the world for her.

Gendry-Kim never makes such a point explicit; like so much here, it exists between the lines. Yet it suggests not only the traumas but also the mutability of history.

“It wasn’t until one day in 1983, when I was in fifth grade,” Jina confides late in the novel, “that I learned my parents had been separated from their families.” The observation is accompanied by three images, two of which reveal the character as she sits writing, presumably, the sentence we’ve just read.

There is an immediacy, an intimacy, that emerges from these panels, which reveal both memory and art-making as processes. Nothing is fixed, Gendry-Kim is suggesting. We know ourselves only from the bits of information we have been allowed to have. This is as true of Jina, slowly peeling back the layers of her mother’s story, as it is of Gwija, trying to live in the present even as she cannot reconcile (or even uncover) the loose ends of the past. “If we meet,” the mother conjectures in a video prepared for her long-lost offspring, “let’s hug and dance together. … Until our countries are reunified, be healthy and stay alive.”

There’s something deeply resonant about the moment, if only in the way it speaks to the tenacity of hope. A similar dynamic exists between Jina and Gwija, each of whom is living parallel timelines. For Gendry-Kim, this is the point, and the contradiction: The impossibility of life is that, even as we ponder its paths, real or imagined, we have no choice but to live it on its own terms. “My luck’s never been great,” Gwija reflects, although, of course, like all the characters here, she is a survivor. “But I have to see Sang-Il before I die.”

For novelist Steph Cha, K-pop band H.O.T. and action film “Shiri” are a few culture predecessors to this hallyu moment of global success for “Parasite” and BTS.

Ulin is a former book editor and book critic of The Times.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.