Barack Obama, Bruce Springsteen talk race, reparations and the American dream in a new book

- Share via

On the Shelf

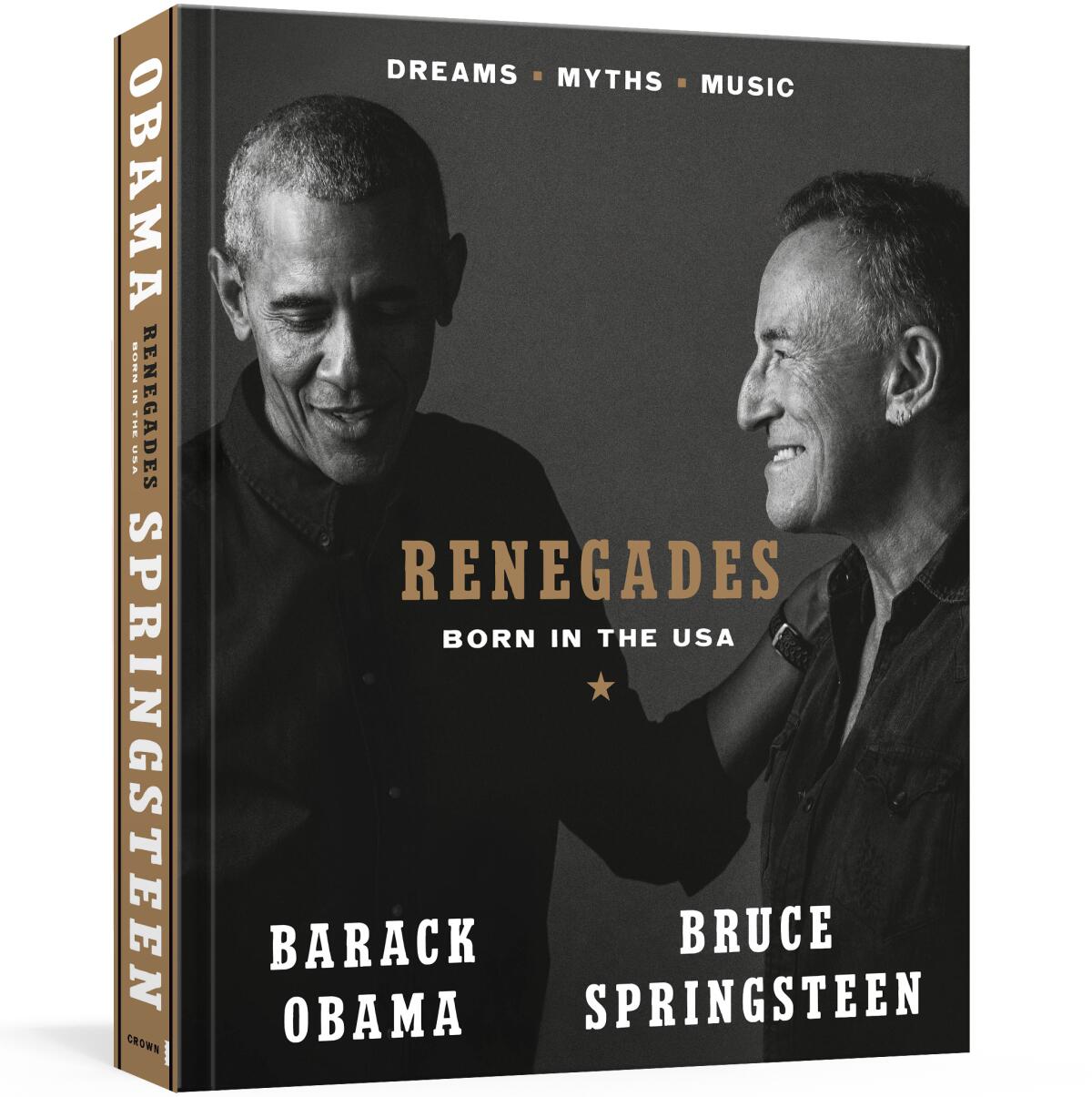

Renegades: Born in the USA

By Barack Obama, Bruce Springsteen

Crown: 320 pages, $50

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

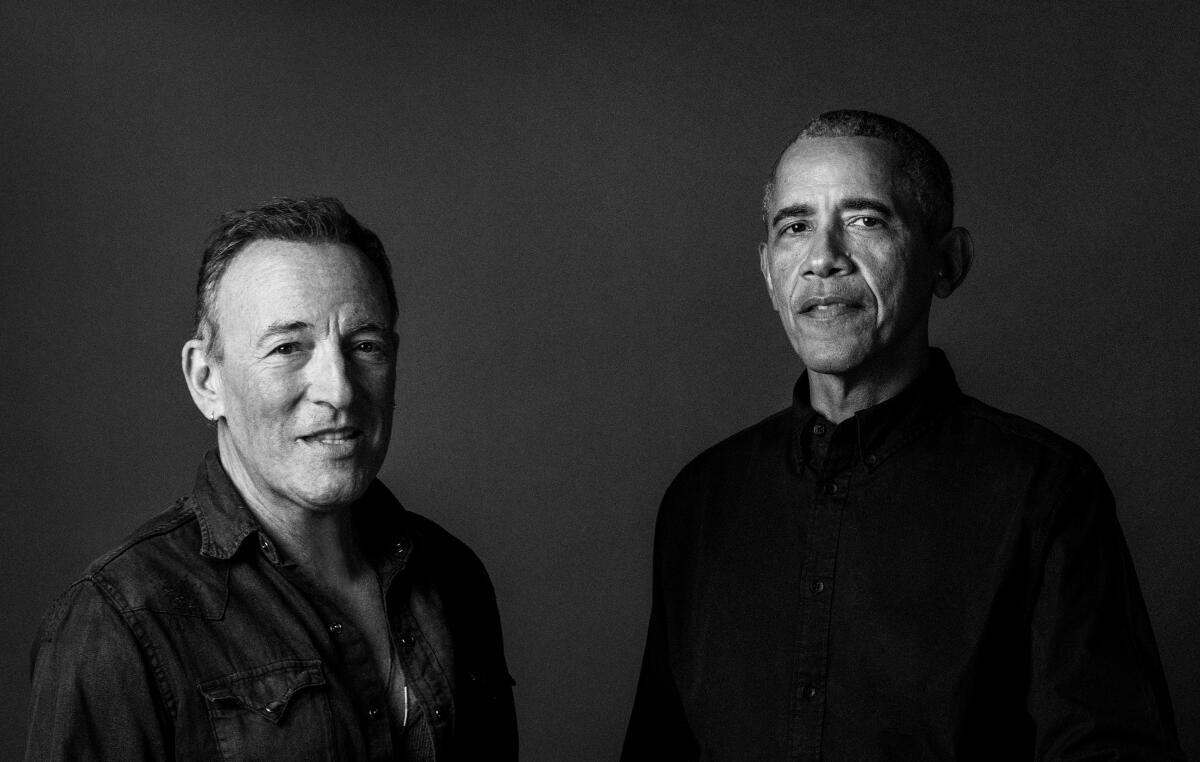

In 2008, an unlikely friendship began to flourish between a rock ’n’ roll legend and an American politician. Barack Obama was campaigning to become the first Black president of the United States, and he invited Bruce Springsteen to perform a concert at a rally in Ohio.

“I had wonderful experiences playing those rallies and those appearances with you,” Springsteen tells Obama in “Renegades: Born in the USA,” a collection of intimate and thoughtful conversations between the president and the Boss, which builds on the duo’s eight-episode podcast series of the same name, released by Spotify earlier this year.

Out this week from Crown, “Renegades” contains unpublished anecdotes along with more than 350 illustrations, photographs and historical documents, including copies of Springsteen’s handwritten lyrics and marked-up drafts of the former POTUS’ speeches.

Openly discussing race, music, masculinity, cultural appropriation and nothing less than the American dream, the pair come off as kind-hearted boomers — grateful for the changes that have marked their lifetimes but realistic about the limitations of their generation and the progress yet to come.

“[You] gave me something that I’ve never been able to give myself,” Springsteen tells Obama in the book. “And that was the diversity that was in the audience. I was playing to white faces and Black faces, old people and young people. And that’s the audience that I always dreamed of for my band.”

Obama, too, marvels at how his audience has evolved. Reflecting on last summer’s police brutality protests set off by the killing of George Floyd, he says it’s been “energizing” and made him “hopeful” to see young people on the frontlines of the movement for racial justice.

“In the sixties protest, it was a more limited band of young people who were getting involved,” Obama says. “But what you’re seeing — and it’s sustaining itself — seems to be a change in attitude that is generational or generation-wide. I am encouraged by the willingness of young people to not only put themselves out there” but to ask themselves and their parents “hard questions. To look inward and not just outward.”

The New Jersey hitmaker followed up with a question about how the former POTUS makes peace with America’s contradictions — with the fact that “the same country that sent a man to the moon is the country of Jim Crow.”

Former President Obama joined filmmaker Ava DuVernay for a conversation about “A Promised Land,” his legacy and activism during a Book Club event.

“I think that it is partly because we never went through a true reckoning,” Obama responds, “and so we just buried one huge part of our experience and our citizenry in our minds.”

Reparations could be part of an eventual reckoning, he says. But he says that “white resistance and resentment” made it unattainable during his presidency and that, while campaigning, he preferred to pursue more practical policy goals.

Progress is stymied, he adds, in a country that still struggles “to provide decent schooling for inner-city kids” — and one where “the resentments, the fears, the stereotypes, the tribal lines that are drawn out in our country remain very deep.”

These were the kinds of divisions he had meant to bridge during his life in politics. In the “beer summit” of 2009, for example, he invited Harvard scholar Henry Louis Gates Jr. and Sgt. James Crowley, the white police officer who arrested him outside his Boston home, to have a conversation with him and then-Vice President Joe Biden.

Instead, five years after leaving office, Obama finds himself confronted with the limits of gradual change, as now-President Biden’s grand agenda comes up against the hard realities of governing in 2021.

“If our criminal justice system and the way we police are broken and we have to start it from scratch,” he asks, “are we obligated to just say that, even if the country is not ready for it? Even if you lose votes, even if you forgo the possibility of making more incremental progress, is it worth it to just articulate that truth?”

Springsteen is equally torn over where the country stands: “We’ve consistently fallen too short for too many years, for too many of our citizens, and that inequality, social and economic, is a stain on our social contract.”

He’s tried to bring awareness where he could — through music. Springsteen recalls the tumultuous reception of his song “American Skin (41 shots),” a response to the 1999 killing of Amadou Diallo, an unarmed immigrant from West Africa shot by New York City police officers in the vestibule of his apartment building.

The first time Springsteen performed the song, in June 2000 in Atlanta, “people mildly applauded,” he recalls. But by the time he played it in New York’s Madison Square Garden later that month, the band was on the front page of the New York Post. “[T]here was a lot of name-calling going on,” he tells Obama.

Diallo’s parents showed up and “were really lovely. But just as the band was starting to play the song, police officers rushed the stage. We took a lot of heat from the police for several years after that, which I always felt was a result of not really listening to the song.”

Twitter can’t agree on whether Bruce Springsteen sings ‘waves’ or ‘sways’ on his 1975 classic, ‘Thunder Road.’ Turns out, Springsteen isn’t sure either.

It’s just one anecdote in a broader conversation about the deep fissures of race, class and politics that — they have to admit — continued to grow despite their efforts.

“So how do you think we can bridge those divides?” asks Obama.

Springsteen offers a few “practical” ideas: “politically connecting across party lines; rediscovering common experience, the love of the country, a new national identity that includes a multiracial picture of the United States that’s real today, rooted in common ideals.”

“Those are hard, hard things to do,” he adds — and you can almost hear his world-weary rasp. “Any way we cut it, it’s a long walk home.”

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.