Review: In Sally Rooney’s new novel, the millennial darling bursts her own bubble

- Share via

On the Shelf

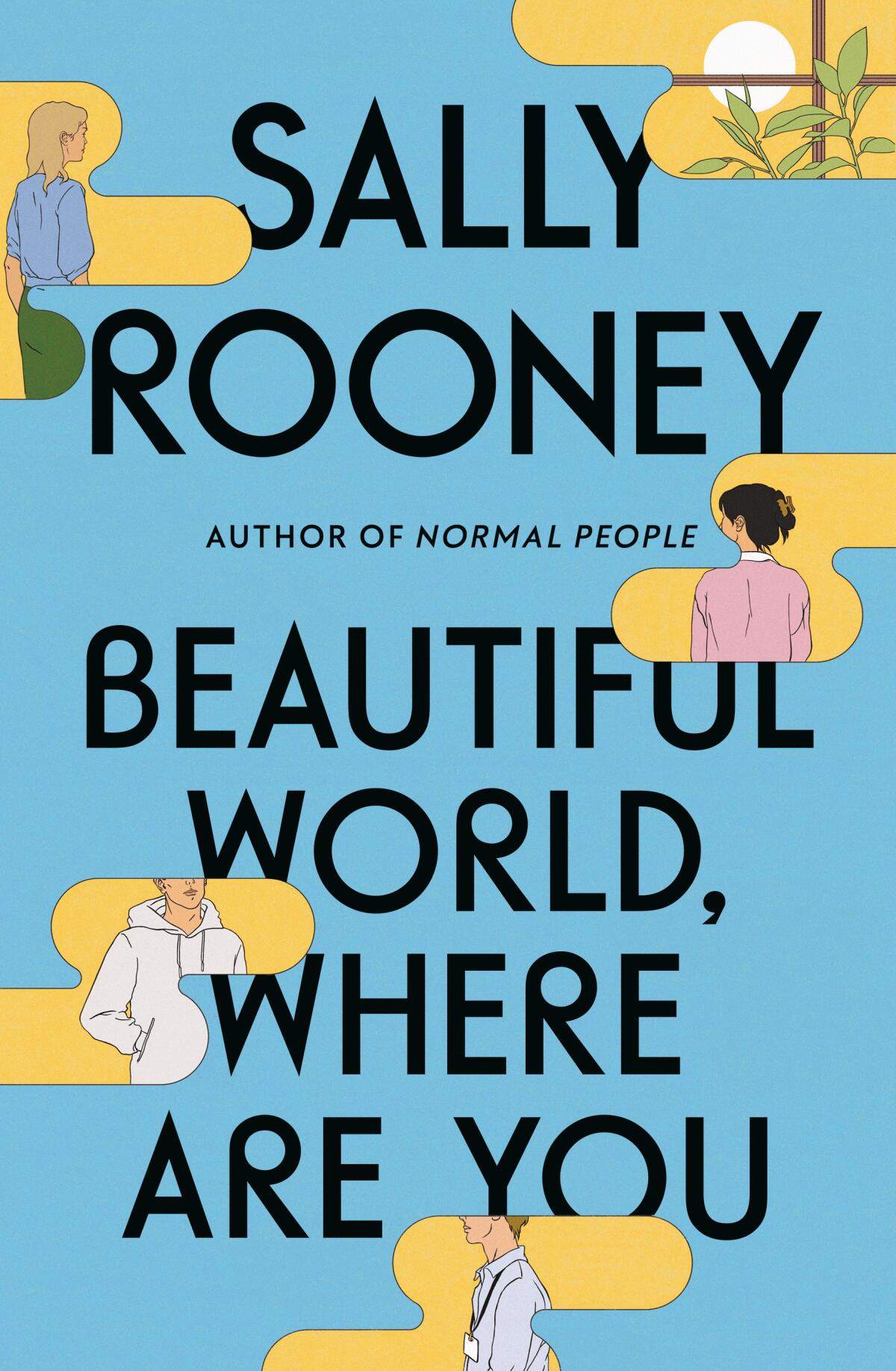

Beautiful World, Where Are You

By Sally Rooney

FSG: 368 pages, $28

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

I quit “Conversations With Friends,” Sally Rooney’s first novel, after 50 pages. Recommended by a high-ranking editor with impeccable taste, the galley had been worked over by several others before me; they’d all, she said, adored it. What didn’t I — a millennial woman and member of the chattering literary class — see in this vibey, au courant ménage à trois plus un?

For a few years, while watching critics race to come up with clever new thoughts on Rooney to borrow some of her shine, I seethed. Here was a 24-year-old scrapper sucking up all the oxygen with a simplistic riff on an age-old plot. I skipped her second novel, “Normal People.”

Then, last year, I watched some advance episodes of the “Normal People” TV series. And read the book. And restarted “Conversations With Friends.” All in about 72 hours. I didn’t merely enjoy floating through the worlds Rooney had conjured — I was enveloped by them. I’d either been wrong before, or I was wrong now, or there was no such thing as wrong. She twisted me up.

All of which is to say that the critic brings her own baggage, and that she doesn’t travel light. Rooney’s work — its Hemingway simplicity cut with jabbering “Gilmore Girls” erudition — has become, for no reason I can ascertain beyond that random spark that sets some literature aflame while so much else molders, an unofficial barometer of taste. We’ve all been making Rooney’s work about ourselves — our tastes and hopes and, mostly, our intellectual reputations — for quite a while now, and probably aren’t inclined to stop.

Well, fire up the tip-tapping critics’ fingers: Her third novel, “Beautiful World, Where Are You” (question mark conveniently left by the roadside), has arrived. Since Rooney’s name has been adopted as the signifier of millennial late-capitalist malaise, purpose-fitted by publicists to market every new book by a bright young woman, it makes sense to start there: In “Beautiful World,” younger Sally Rooney meets older Sally Rooney, and the two smash it out over whether any Sally Rooney deserves to write bestselling fiction about bright young thinkers with their hands in each other’s pants.

In adapting her novel “Normal People” for Hulu, Sally Rooney and director Lenny Abrahamson tried to “tap into the silence of the book” to capture its essence.

What do we want from our biggest novelists? What kind of novel ought someone like Rooney — burnished and then strip-mined, too famous for her own good — write now? “Beautiful World” is ostensibly about a tetrad of thirtysomethings: Simon is a beautiful do-gooder working in politics, pulled in and out of an almost-relationship with Eileen, the managing editor of a small Dublin literary magazine and once the toast of her college. Meanwhile, an irascible warehouse worker named Felix meets Alice, Eileen’s best friend and the author of two novels whose success has pushed her toward the life of a seaside recluse. Alice, by dint of her sharp tongue and her Rooney-ness, holds the reins most firmly.

Rooney recently told Vogue that she “can only” draw on her life for material; we’d be kidding ourselves if we pretended Alice is not a stand-in for Rooney, who also sold her first novel for six figures at age 24, moved from Ireland to New York and back again, and humped it around the globe on an interminable press tour.

“I can’t believe I have to tolerate these things,” Alice writes in an email to Eileen, “having articles written about me, and seeing my photograph on the internet, and reading comments about myself. When I put it like that, I think: that’s it? And so what? But the fact is, although it’s nothing, it makes me miserable, and I don’t want to live this kind of life.”

Simon, Felix and Eileen struggle to understand why they haven’t ascended beyond work as drudgery. But Alice sees that success is a trap, that it commodifies you into an objet, something to spin around and see how it catches the light. Alice would hate this review.

Her critique puts “Beautiful World” at odds with itself. The structure and plot are pure Rooney: Sentences so minimalist that they feel like literary versions of Donald Judd boxes; exquisite, tense sex scenes better than any moan-y porn; pint glasses clinking over conversation about who really constitutes the working class.

But Alice’s complaints aren’t just about her million sitting in the bank and the toady outgrowths of fame. In emails with Eileen, which make up a large portion of the novel, she explains that she can’t read contemporary novels at all — that she knows the writers now, and they “write their sensitive little novels about ‘real life’ [but] most of them haven’t so much as glanced up against the real world in decades.” Her own books, she recognizes, are “the worst culprit in this regard.”

Novelist Lynn Steger Strong on the revolutionary passivity of Rachel Cusk, Ottessa Moshfegh and Sally Rooney — how we’ve misread them and what comes next.

Of course, this is the issue with Rooney too. Her novels pump in boosts of old-world elegance via jaunts to Italy or roomy seaside rectories; her white characters inhabit the world of wine-swirlers and are often impoverished by choice. The secret of her success, for all the political angst, is that glint of sunny pleasure: money. It’s why her book jackets — bright pastel backgrounds with smoothed out figures — are so frequently imitated. Gotta glom onto that Rooney magic.

Her characters’ manic political declarations — Alice and Eileen dash off emails about what we can learn from the fall of the Bronze Age and the rise of single-use plastics — add an extra glaze of intellectual cred, and Rooney, nothing if not self-aware, knows it. “Beautiful World” is constantly trying to poke holes in itself to see if it will deflate. Sometimes it feels like a beta test in which the sales numbers and critical reception will decide which Rooney (the younger or the elder) makes an appearance in novel No. 4.

For all the talk of Rooney as a groundbreaking voice of her generation, the new novel is an old-fashioned comedy of manners — the sort of “breaking up or staying together” novel Alice and Eileen debate in their emails. There’s more than a whiff of Shirley Hazzard here, a slightly more earthbound “Transit of Venus.” And its roots in the Victorian novel grow above the ground: Rooney circumvents the problem of parents by making them all unbearable or dead, organizes the drama around a small social milieu delineated by and obsessed with class and builds up to a gathering of all its characters in one place — a reckoning.

Combine that with the composure of Rooney’s quiet, decisive voice. She writes every sentence as if it were a screenplay for an uncluttered film. On her way off a bus, Eileen “deposited her chewing gum back into its foil wrapper and threw it into a nearby waste bin.” Two ice cream dishes rest in a glimmering sink. Clothes are simple and neat, floors are swept and tidy, no detritus is permitted in her syntax. This is the language of simple pleasures, easy to digest, satisfying. Rooney’s novels make great television shows because that’s what they already are.

An Irish millennial’s first novel, “Exciting Times,” pins the touchstone generational tension between sardonicism and sincerity.

All of which is to say that “Beautiful World” is a paradox. Sally Rooney seems to be done with the cult of Sally Rooney but beholden to her style, her proclivities. She won’t be able to shake them so easily; her premises aren’t resistible enough. “Beautiful World” tries new structural gambits, but these (especially a lame, inadvisable coda) feel painstakingly collaged — unsuccessful breaks for freedom. Rooney’s first two novels read like one long exhalation, but this one sometimes requires an inhaler.

“Am I,” she seems to be asking, “a writer, or a phenomenon?” I’m not sure why she thinks they’re mutually exclusive.

Kelly’s work has been published in New York Magazine, Vogue, the New York Times Book Review and elsewhere.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.