A bilingual novelist’s family saga plumbs the allure and the menace of ‘L.A. Weather’

- Share via

When author María Amparo Escandón moved to New York from Los Angeles in 2014, she’d often hear New Yorkers claim L.A. has no weather.

“What do you mean there’s no weather in L.A.?!” she’d exclaim, before countering with the Santa Ana winds, fires, drought and — yes — rain. “It’s not always 72 and sunny.”

Contemplating L.A. from 2,800 miles away, Escandón had a revelation. “This is actually a city that depends so much on the weather,” she recalled on a recent afternoon in her Brentwood home. “Think about how many people immigrate to L.A. because of it. Once they get here they realize you have to take three-minute showers and you probably shouldn’t water the lawn.”

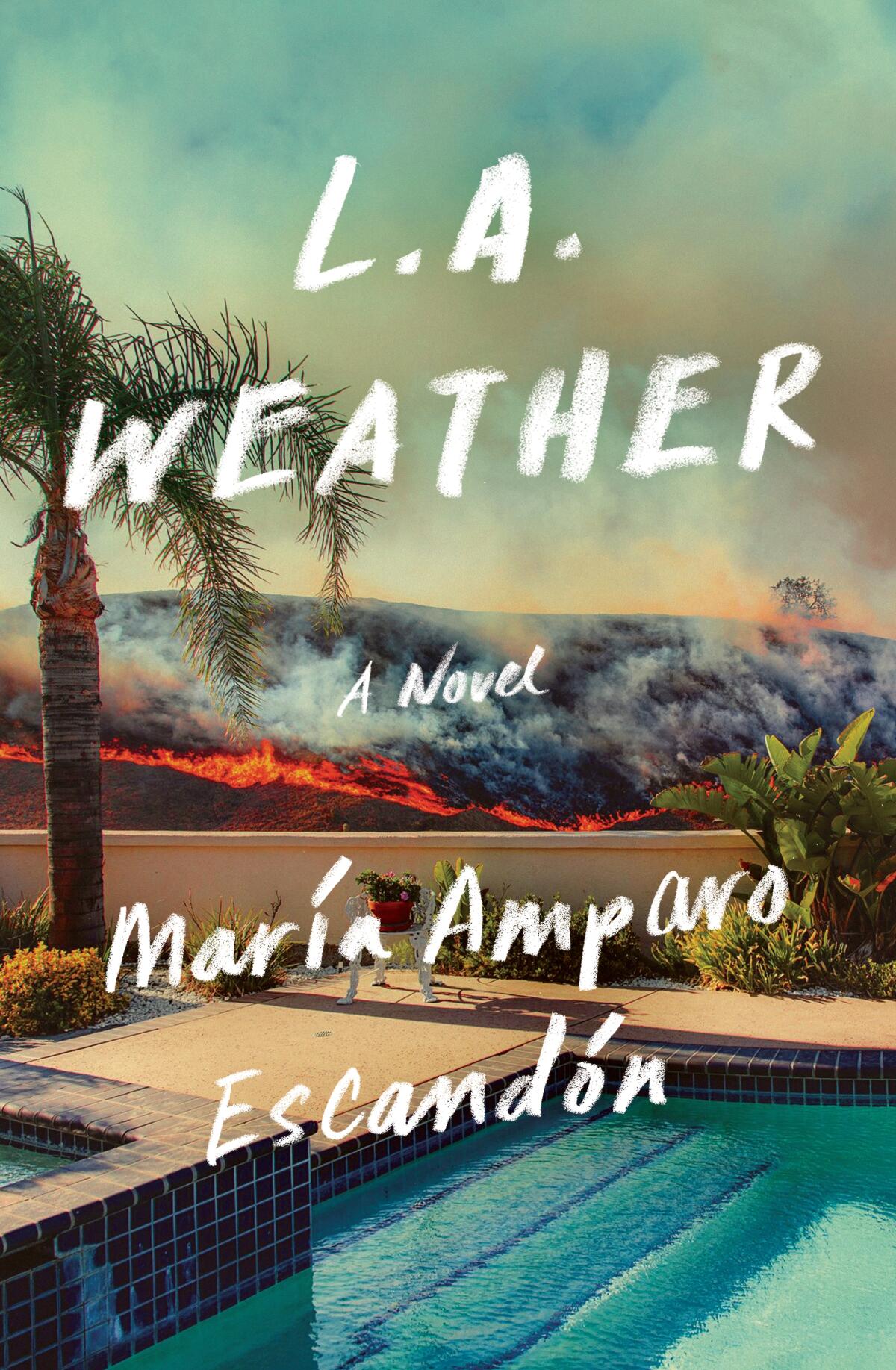

The fuse was lit for Escandón’s third novel. Out Sept. 7, “L.A. Weather” follows the Alvarados, an affluent Mexican American family grappling with secrets, betrayals, close calls with death and climate disasters.

Set during the tail end of one of California’s driest periods on record, the story unfolds over the calendar year of 2016. All the weather events in the book — every fire, rain and full moon — actually happened. Except for one: “Toward the end, there’s a rain that wasn’t,” she said, laughing. “I really needed it to rain that day.”

Put plainly, there’s drama — lots of it. “I think the narrative of the telenovela is so ingrained in my head that whatever I write comes out as a telenovela,” she said. But at its core, the book is an ode to the adopted hometown with which she’s had a passionate on-and-off relationship for nearly 40 years.

“L.A. is a high-risk, high-reward place, which makes it a perfect backdrop for her characters,” said Betsy Amster, Escandón’s literary agent. “I love her ability — or her determination — to find the humor in life’s risks,” she added.

Like the Alvarados and many Angelenos, Escandón lives in a wildland-urban interface — a transitional zone in which wilderness and built environment collide. “That’s the most dangerous area when there’s a fire because it’s not the mountain burning, it’s homes burning. It’s people evacuating,” she said. But when it isn’t on fire, it’s beautiful and serene.

Oscar, the patriarch of the Alvarado family, plagued by recurring nightmares of homes engulfed in flames, describes the zone as a place “where your surveillance camera can spot a mountain lion roaming in your backyard while you sleep … where you could discover a deer and her fawn just a few feet away from the eight-lane 405 Interstate freeway,” a place “both awesome and terrifying.”

Like her characters, Escandón has been evacuated from her home. The first occasion was the Skirball fire of 2017, on the day she returned from that four-year stay in New York. (“Some welcome!” she said.)

“This should be a year-round enterprise, now that fires are year-round as well,” Los Angeles Mayor Eric Garcetti said.

The second was the Getty fire two years later. She pulls out her phone and finds a photo taken from her dining room window at 2:46 a.m. that October day in 2019, just before she fled with her two cats and a friend visiting from Brazil. A giant plume of neon orange smoke rises just on the other side of the 405. The wind changed direction that night and the fire didn’t jump the highway. She got lucky.

She knows it won’t be the last time she has to flee.

Urban and rural life have always been intertwined for Escandón. She was born to a family of ranchers in Mexico City. Her father, Julio, had a raspberry farm, and she spent her youth riding horses, covered perpetually in dirt. She was 7 when she told a hurtful lie; it’s also when she began to write.

She tells the story like this: María accuses the nanny of pinching her arm and shows her mother a bruise to prove it. Furious, her mother fires the nanny. Guilt-ridden, the girl confesses: The bruise was from an immunization. She is grounded, and her grandmother explains to her the difference between lies and storytelling. She hands María a notebook, which the girl spends so much time writing in that she flunks second grade.

At 13 Escandón spent a year on a pig farm in Minnesota to learn English. Years later, she would take a creative writing class at UCLA Extension and become a bilingual writer. (She published her first two novels, “Esperanza’s Box of Saints” and “Gonzalez & Daughter Trucking Co.,” in English and translated them into Spanish.)

At 23 she moved from Mexico to L.A. — not for weather but for love. She and her then-boyfriend lived in a small room inside their friend’s pornographic theater in Pico-Union, surviving on concession-stand food and attempting to launch a Spanish ad agency “with no money, no clients, no credit, no office.”

“You know when you’re really young and you don’t know you can’t do something and so you do it?” she asked. “It was ignorance, a little bit of arrogance, a little bit of, ‘Yeah, why not?’”

But the American city quickly worked its way into her: its ever-evolving gastronomy, its culture and “fantastic” weather, its “fabulous expressions of architecture.” Many of her passions are reflected in the Alvarado family. Sisters Claudia, Olivia and Patricia are, respectively, a professional chef, an architect (who feels guilty for abetting gentrification) and a social media guru. Keila, the matriarch, is a ceramicist — another passion of Escandón’s.

Oscar, always absorbed in thought, channels Escandón’s fascinations with L.A. Walking down a street in Pacoima on a hot August morning, he ruminates on the “hundreds of cities” contained within one.

“People who knew little about L.A. imagined everyone walking around with a screenplay soggy with sweat underneath their armpit,” Oscar thinks. “This was the birthplace of Hollywood, after all. But in truth, Los Angeles was whatever you wanted it to be, and that was thanks to the constant influx of immigrants arriving with their dreams...”

During the pandemic, book sales rose across the U.S. This fall, publishers are counting on major releases to keep it up — but also a return to normal.

Alex Espinoza, a writing professor at UC Riverside, was struck by Escandón’s ability to write about L.A. with nuance.

“She knows the complexities of the neighborhoods, their terrain, but also their ethnic makeups,” he said, and she “complicates our view of Latinos. She understands that Latinos’ experience is complex and not easily categorized.”

Escandón is currently busy “transcreating” “L.A. Weather” into Spanish. Self-translation is challenging and requires self-control. “I can’t do a literal translation because I get carried away.”

Writing her novels in her second language was a way, she said, to practice writing in English. This time, she believes she’s mastered it. “With ‘L.A. Weather,’ I feel like I’ve finally come home” to the English language, she said.

She also has grown alert to the precariousness of home. Between her first and third novel — as heat waves became more frequent, droughts more prolonged and wildfires deadlier — it dawned on Escandón “that this is a new reality: We’re going to be living with wildfires in the state of California.”

But like the Alvarados, she has adapted to it. “It’s there in the background all the time.” In L.A., it’s just the weather.

In 2016, Jaime Lowe read the obituary of a female inmate firefighter. Five years later, her new book opens up the world the woman lived and died in.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.