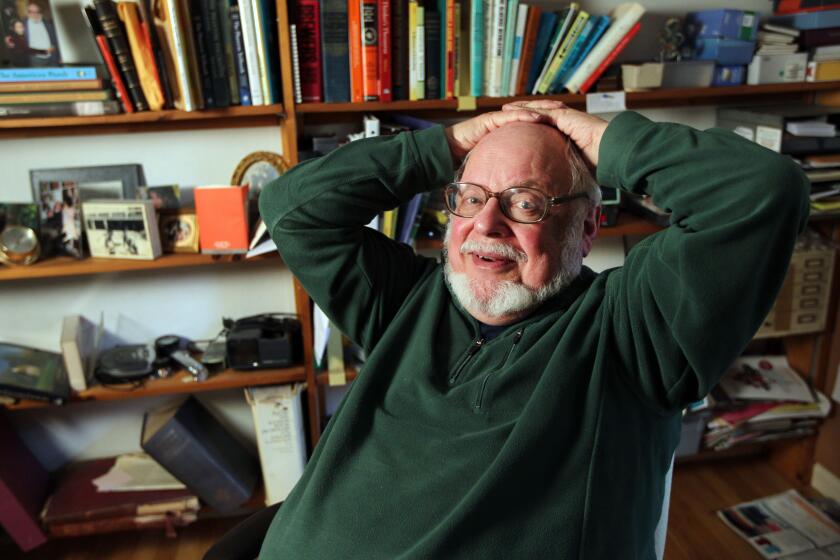

Remembering ‘The Very Hungry Caterpillar’ author Eric Carle

- Share via

Eric Carle wrote books that refuse to stay on the shelf. In bookstores, of course, his titles have vanished from shelves for decades, whisked off in the millions by parents and grandparents, by aunts and uncles and teachers. Anyone who needs a present for a young child or baby knows you cannot go wrong with “The Very Hungry Caterpillar,” “Brown Bear, Brown Bear, What Do You See?” or (my personal favorite for obvious reasons) “The Grouchy Lady Bug.”

After being tidied away, all manner of perfectly lovely and readable children’s books can be expected to remain exactly where they were put until an adult pulls them out again. Carle’s books refuse. They jump off the shelves when Mom or Dad, or Nana or Pop Pop, aren’t looking; they can be found lounging about on floor or bed or table, open and closed, their iconic splodges of color, which Carle magically turned into instantly recognizable shapes, innocently beaming up at you.

Kids cannot keep their hands off them. They love them. They love them to the point that if you have to read that damn book to them one more time, you will go smack out of your mind; and anyway, you have them completely memorized; and when you close your eyes even for a minute you can see that red bird or pickle or lady bug etched against your eyelids, possibly for the rest of your natural life.

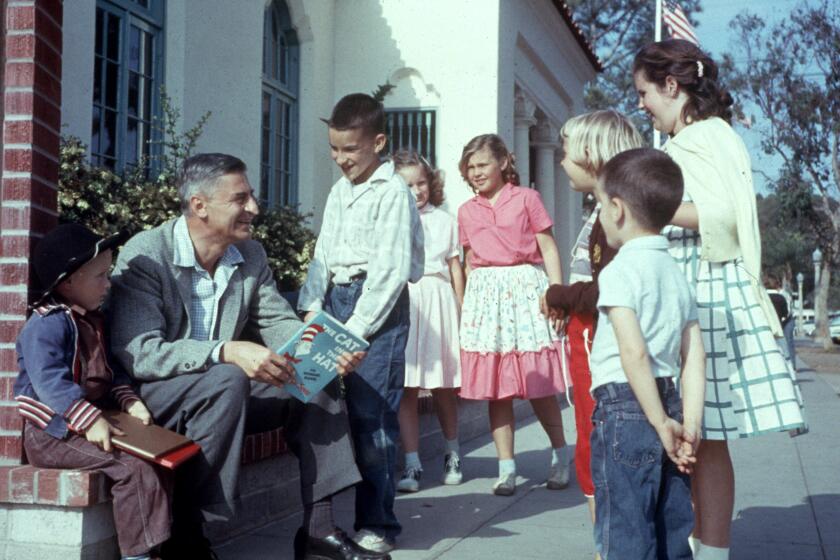

But of course you read them. Again and again and again. They are lovely, soothing, gently amusing, utterly predictable and completely comforting. Unlike “Where the Wild Things Are,” they do not require a range of vocal tones to capture language designed to mimic adventure or rile kids up. Where Dr. Seuss is rock ‘n’ roll — manic and funny, words twisting in their double meanings, all manner of crazy creatures zipping in and out of trouble — Eric Carle is simple and stately as a waltz.

He created true picture books, alive with captivating images and narratives that unfolded through repetition and mild revelation, the perfect disguise for stories that taught color, counting and the art of reading.

Kids know where they stand with an Eric Carle book: front and center. He saw the world as they did, filled with things that needed to be observed, identified, counted and connected, all of which were important enough to bear repeating.

Below are a few stories from our staff about their encounters with Carle – as kids, as parents, as families — beginning with my own.

— Mary McNamara

A beloved children’s author and illustrator whose classic “The Very Hungry Caterpillar” and other works gave millions of kids some of their earliest and most cherished literary memories, has died

Mary McNamara

My family went through at least five copies of “The Very Hungry Caterpillar,” but it was “Brown Bear, Brown Bear” that wove itself into our life, inextricably.

My son Danny has always loved books, but when he was in kindergarten he, like many boys, struggled a bit in the reading department. He was our first child and no doubt we didn’t help much — what with our nightly “homework” reading of the dreaded Bob books and our over-enthusiastic assurances that he would “get it” soon enough.

One night, as I got them into bed, his 3-year old sister, Fiona, picked up “Brown Bear” (from the table — it never seemed to make it to the bookshelf) and began to “read” it out loud. Danny burst into tears.

I would like to say Fiona did not take the opportunity to look smug, but that would be a lie — little sisters enjoy their triumphs where they can. Fortunately, she soon made the fatal error of turning two pages instead of one but continuing to “read” the book in proper order, allowing me to convince Danny that she was reciting, not reading.

That is, of course, how many of us learn how to read — memorizing sounds and attaching them to the shape of letters and words — but I didn’t feel this was the time to point that out.

Everyone calmed down, Danny soon became an insatiable reader, and over the years a well-placed “Brown Bear, Brown Bear, What do you see?” often defused those maddening “did too/did not” arguments that can force parents to wonder if their decision to quit smoking before they had kids hadn’t been a trifle hasty.

Norton Juster’s “The Phantom Tollbooth” was published in 1961, with illustrations by Juster’s roommate at the time, Jules Feiffer.

Meredith Blake

One of the most urgent but underreported challenges of being a parent is finding books you can stand enough to read aloud to your kids hundreds — potentially even thousands — of times without completely losing your mind. There are books your kids will want to hear over and over again that you will read to the point that you can recall every word, every image, every plot twist more readily than your own social Social Security number. Some of them will be so inane or irritatingly nonsensical that you will rue the day they were written, then accidentally-on-purpose misplace them behind the couch.

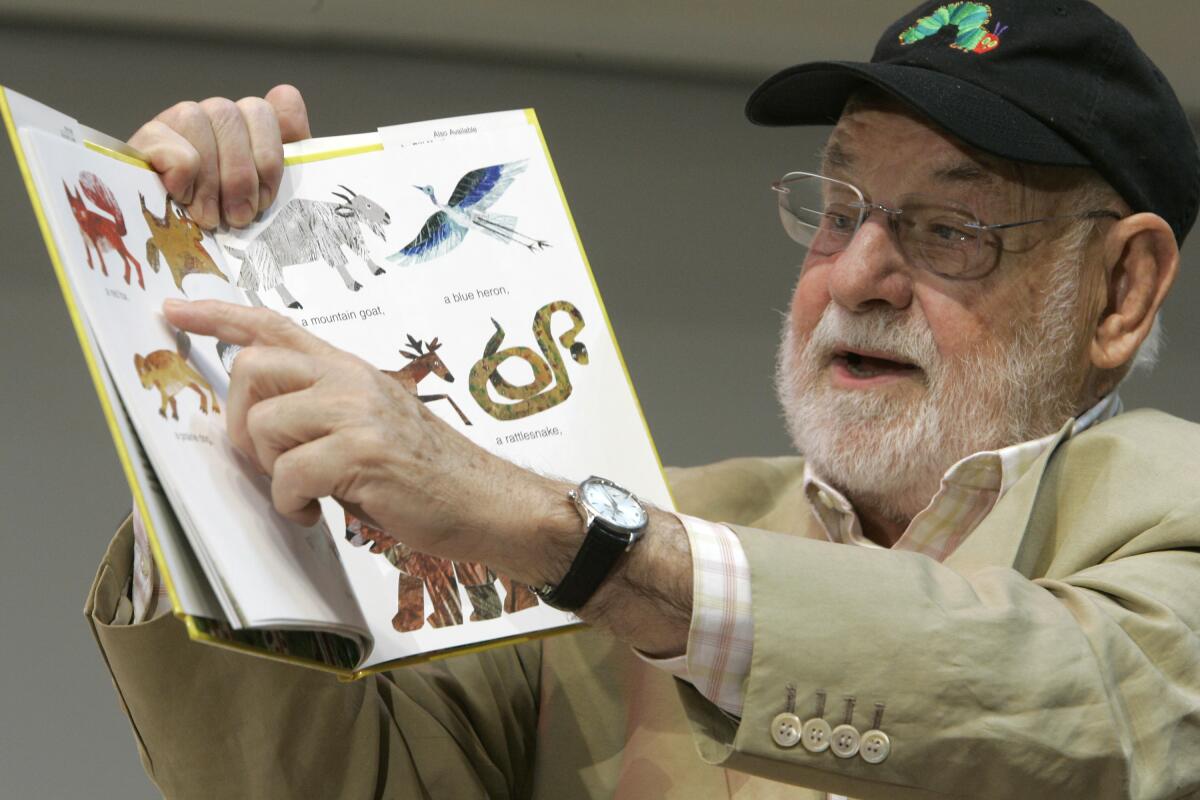

Then, mercifully, there are the books by Eric Carle, which have been beloved by multiple generations because you can’t really go wrong with the colorful collage illustrations, the whimsical designs that turned the book itself into part of the narrative (pages with holes in them!), or the gentle life lessons about kindness and patience centered on the natural world. Pretty much anyone born after 1970 grew up with “Caterpillar” on constant rotation, so for those of us who are parents now there’s the added pull of nostalgia.

While the classics — “Caterpillar” and “Brown Bear” — are staples in our house, as they have been in millions of others, my children really seem to gravitate toward a Carle deep cut, “From Head to Toe.”

In the book, one creature after another shows off its signature gesture — there’s a chest-thumping gorilla, a foot-stomping elephant — then invites the reader to do the same: Can you do it? In response, my daughters eagerly wave their arms like monkeys and kick their feet like donkeys but sometimes struggle to “raise their shoulders” like a buffalo. Figuring it out is part of the fun. It’s an engaging little book that, yes, helps toddlers expand their vocabulary and recognize an array of animals and body parts. But it also empowers them through play. Best of all, it lets you, the parent, be the audience and watch your kids ham it up.

The pivot from Dr. Seuss’ books during a national event founded to honor him seems sudden, but for the NEA and local teachers it was a long time coming.

Daric Cottingham

“The Very Hungry Caterpillar” was one of the first books my parents read to me when I was born in 1996. It was one of my favorites.

By the time I was learning to speak, the book had become my encyclopedia. I would mimic the title character, constantly exclaiming, “I’m so hungry!” The book taught me colors, days of the week and varieties of food. It also sparked my interest in metamorphosis.

It was my first exposure to creativity. I would draw and color pages from the book for my mom to hang on the fridge. Now, 25 years later, I find time each week to make art — mixed media, paintings and digital drawings. Still emulating Eric Carle, I mix and blend colors, reaching for the innocent whimsy of those first years of my life.

Carle’s ultimate gift was the idea of creation, the notion that every transformation in life is the invention of something new.

When I grew older and became an uncle, I read it to my niece and nephew, who will continue to pass it on — sparking new generations of creation and change, a gift that won’t stop giving.

Eric Carle has worked on a stack of books over the years, but his caterpillar has chewed its way to the top.

Aida Ylanan

When teaching kindergarten, the foundation for all kinds of life skills, where do you begin? For many teachers around the U.S., including my mom, it was “Brown Bear, Brown Bear, What Do You See?”

A now-retired kindergarten teacher of 34 years, mom turned to Bill Martin Jr. and Eric Carle’s picture book every year to teach the stuff of life. It taught colors, of course: At the end, students could name every shade of the rainbow, even if they would never find a blue horse in real life.

They would also learn the shapes while creating paper reproductions of each animal: a red triangle for the red bird, a purple oval for the cat. Cutting out these figures was a lesson in itself, teaching small hands clasped around safety scissors some fine motor skills.

Long after the last student went home, my mom sat in her classroom and assembled these pages of colors and shapes into a thick construction paper book -- one for every student, compiling their hand-made art -- for everyone to take home and read to their own parents. Out of one book came 30.

It’s hard to overstate the impact Eric Carle left on generations of readers, including me; his work is embedded in our first memories of learning. I’m inclined to believe more well-worn copies of “The Very Hungry Caterpillar” are read and passed down than bought new.

The copy my mom read to her students is the same one she read to me and my older brothers. All the books we read as kids were passed down to my mom’s classroom library; our last name is handwritten in Sharpie at the corner of every cover, with errant stickers or drawings inside.

Children’s books were as essential to our family as they were to my mother’s profession. On Christmas Day, 1999, both my brothers, ages 12 and 13, gave my mom a gift they thought fitting for teacher-types like her: “The Very Quiet Cricket,” complete with a chirping soundbox in the middle.

Springtime in mom’s classroom was the domain of Carle’s most famous, omnivorous creature. The book is her favorite. “The students are always amazed that the caterpillar can turn into a butterfly,” she remembered. They sing butterfly songs and make butterfly handprints fashioned after the technicolor wings of Carle’s original illustration.

Springtime also marks the culmination of the school year — nine months, a drop in the bucket to an adult but what feels like a lifetime of growth and learning to a five year old in school for the first time.

Bringing Carle’s story to life, my mom mail-ordered live caterpillars every year from the science education supply store. They lived in a mesh cage and grew bigger, much like the hero of Carle’s book, until they crawled and wiggled toward the top of the container, turning themselves into chrysalises.

Once the critters emerged, transformed, every kindergarten student gathered outside in a big circle to celebrate them. Together, they named each new friend and watched as my mom opened the cage and, one by one, let the butterflies go.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.