Carribean Fragoza lives the life she writes — busy, creative and slightly surreal

- Share via

2021 L.A. Times Festival of Books Preview

Carribean Fragoza

Carribean Fragoza appears April 23 on “Fiction: The Art of Short Story” with Ben Okri, Deesha Philyaw and Shruti Swamy, with Dorany Pineda moderating.

RSVP for free at events.latimes.com/festivalofbooks

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

When Carribean Fragoza was a child, she ate dirt. “Like I ate dirt a lot,” she said in a recent video interview. And her tías in Guadalajara, Mexico, really liked eating clay pots. They’d break off little pieces and hand them to her “like they were chocolate.”

During one of her first prenatal appointments decades later, the obstetrician, concerned about lead in her body, asked Fragoza if she had eaten dirt as a kid. She responded delightedly: “Oh! Why yes I did, actually!”

These tidbits of personal medical history — the odd diet and the maternal anxiety — “made their way into the story,” said the 39-year-old author, journalist and artist. That story is “Eat the Mouth That Feeds You,” about a young daughter who bites chunks of her own mother’s flesh. “It is her right,” says the mother in the short story. “She must take those things. She must take from me what she needs.”

It’s a fitting title piece for Fragoza’s debut collection, released in late March but already widely acclaimed. “Eat the Mouth That Feeds You” includes fantastical, intimate, strange and often supernatural stories set on both sides of the U.S.-Mexico border about Latinas navigating a male-dominated world — and leaning on one another for support. Fragoza will join writers Ben Okri, Deesha Philyaw and Shruti Swamy on April 23 for an L.A. Times Festival of Books panel on the art of short stories.

Reviewers have described the collection with words like “horror” and “gothic,” but Elaine Katzenberger, her editor at City Lights Books, prefers “intensely loving” and “wry.”

“Her characters are treated with a kind of maternal compassion as they struggle,” Katzenberger said in an email, “and the appeal is a veneer of straightforward, plainspoken presentation that encourages a reader’s complicity and sympathy” — the better “to accept as fact a quasi-mythological journey.”

Fragoza wrote these tales over many years; some date back to her undergraduate years at UCLA and then at CalArts, where she earned an MFA in creative writing. Like most of her writing, they started as images, emotions or voices that she’d scribble on envelopes or bills or in notebooks while writing articles or to-do lists.

But she never intended to compile them into a single book. “I really wanted my first book to be a novel,” she said, “and that kind of prevented me from seeing these stories as a collection for a book.” With the encouragement of a friend and mentor, she relented.

It’s not as though she had nothing else going on. Despite the uncertainties and stressors of a pandemic, Fragoza has had a “strangely productive year.” She co-edited and contributed to “East of East: The Making of Greater El Monte,” published in February 2020. In July, her family moved from Fresno to Claremont after her husband, historian Romeo Guzmán, was offered a teaching job. She accepted a part-time job as coordinator of the Kingsley and Kate Tufts Poetry Awards while freelancing as a journalist, preparing to publish this book and helping raise two daughters — Camila, 2, and Aura, 9. She is also codirector of the South El Monte Arts Posse; co-edits the UC Press’ acclaimed Boom California; and recently launched “Vicious Ladies,” a digital zine of cultural criticism by women and nonbinary people of color.

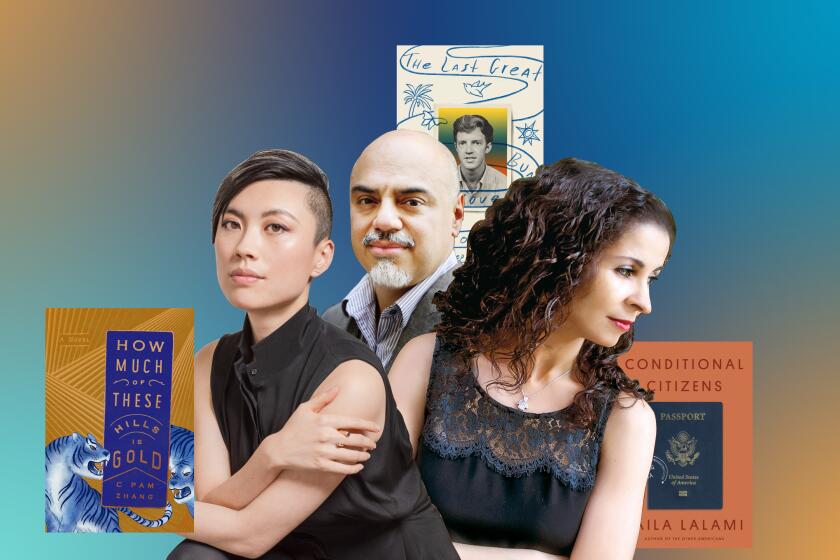

Immigrant memoirs and essays, twisty historical novels by C Pam Zhang and Rishi Reddi, celebrations of Octavia Butler and “The Last Great Road Bum.”

“That’s a lot of stuff,” she said with a sigh, as her eyes fixed on a slew of handwritten reminders taped on a wall in front of her. “I’m looking at my deadlines” — which she calls “traumatic,” “horrible” but “really useful” — “and thinking, ‘We are so off the rails right now.’”

The daughter of Mexican immigrants, Fragoza was raised in a small back house in South El Monte. Her mother, a homemaker, believed the home is the center of a woman’s life. But she also supported Fragoza’s early love of books and “quirky, artsy interests.”

“I have a lot of memories, especially lately since the pandemic started, of spending a lot of time at home, in a small house, very close to my family and trying to find spaces within my imagination to grow,” Fragoza said.

Today, free to explore every interest via her patchwork of creative gigs, Fragoza sometimes finds herself struggling to find a balance between parenthood and creativity. Not that she’d do it differently. “I feel like in a lot of ways I’m trying to reinvent what it means to be a mother,” she said. “And I think that pushing back on the patriarchy is so key. Like we gotta tear that s— down.”

Yet in her writing, her upbringing is never far from the surface. One story in “Eat the Mouth That Feeds You,” “Sábado Gigante,” was inspired by the variety television show of the same name — a big part of her childhood.

Other inspirations are more ethereal. In the collection’s final story, “Me Muero,” a woman unexpectedly dies during a family party and narrates the experience of feeling her body decompose. “I hate to admit it but I’m going to admit it anyway,” Fragoza said. “That story came to me in a dream.”

Yes, the story is about dying, but it’s really about figuring life out without much help.

“As the child of immigrants, I often felt like, especially being the oldest daughter, there was no real road map. I didn’t always know what I was doing and my parents didn’t speak English for a long long time, so I would have to translate things to them,” she said. “Going to college — which I knew was really important — they didn’t know how to help me with things like that, so I had to figure it out on my own.”

The role models she learned and read about in school never appealed to her. Like Benjamin Franklin, whom she thinks about a lot. “He’s supposed to be a cool guy and he did something great, but I just felt like, ‘Gosh, these people are so boring. I don’t want to do that.’ ... If I was going to be a doctor or a lawyer or something like that, I would know what those steps are, but if you wanted to be a gender-nonconforming-tomboy-writer-artist person, then how do you do that? I didn’t know. So I just sort of fumbled my way through it and got help whenever I could.”

The festival will be virtual for the second year in a row, but expanded from 2020, hosting close to 150 writers over seven days beginning April 17.

It worked out for her. Despite a busy year, Fragoza has been hard at work on two novels. One is about a girl gone missing who joins a “group of radicalized bird watchers” to protect a natural space in her community. It’s set in a place not unlike El Monte.

The other novel was inspired by the construction of Fragoza’s grandmother’s house in Mexico over the course of 50 years. “It wasn’t completed until after she died,” she said.

Before all that, she hopes the stories in “Eat the Mouth That Feeds You” destabilize readers’ sense of reality.

“I want them, and I want me and I want everybody, to imagine a new world” — to envision a place where readers can “wiggle out of gravity a little bit and find new ways to be, to fly off in other directions.”

That kind of experience might make it easier to imagine the world Fragoza has spent a lifetime constructing for herself.

“I have an arts collective and I have all these things,” she said, “and they don’t always make sense to people but I feel like I need to shift away from the demands and restrictions of reality. And I just hope people will give themselves that freedom.”

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.