Review: A survivor’s memoir on sickness and health — ‘we are all terminal patients on this earth’

- Share via

On the Shelf

Between Two Kingdoms: A Memoir of a Life Interrupted"

By Suleika Jaouad

Random House: 368 pages, $28

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

“Write as if you were dying,” Annie Dillard advised in her 1989 book “The Writing Life.” It’s a piece of wisdom Suleika Jaouad has taken to heart. Diagnosed at 22 with myeloid leukemia, she spent four years in the country of the sick and dying before returning to the landscape of the well. But is there really a divide between health and illness? “We are all terminal patients on this earth,” Jaouad reminds us. “[T]he mystery is not ‘if’ but ‘when’ death appears in the plotline.”

Such a conundrum sits at the center of “Between Two Kingdoms: A Memoir of a Life Interrupted,” Jaouad’s account of her sickness and recovery. The book’s title has a pair of antecedents. The first is “Life, Interrupted,” the video and text blog Jaouad began to write for the New York Times in 2012, a year after her diagnosis. The second is Susan Sontag, who in “Illness as Metaphor” wrote, “Everyone who is born holds dual citizenship, in the kingdom of the well and in the kingdom of the sick.” For Jaouad, this split asserts itself during her senior year at Princeton, when she begins to suffer from an unbearable itch.

“I itched during my part-time job at the campus film lab,” she tells us. “I itched under the big wooden desk of my library carrel. I itched while dancing with friends on the beer-soaked floors of basement taprooms. I itched while I slept.” Accompanying the itch is an all-encompassing exhaustion, and skin “so pale it was nearly translucent. My eyelids were a robin’s egg blue, as if all of the veins had floated to the surface. Even my lips looked drained of life force.”

When Jaouad is diagnosed, her first response is relief. “After the bewildering months of misdiagnosis,” she writes, “I finally had an explanation for my itch, for my mouth sores, for my unraveling. I wasn’t a hypochondriac, after all, making up symptoms. My fatigue was not evidence of partying too hard or an inability to cut it in the real world, but something concrete, something utterable that I could wrap my tongue around.”

Emily Rapp Black lost her toddler to Tay-Sachs disease. She talks to a fellow griever about ‘Sanctuary,’ her follow-up memoir about rebuilding a life.

Here is the key to “Between Two Kingdoms” — Jaouad’s disarming honesty. There is no self-pity in this telling and few of the expected pieties. Rather, what we get is a young person wrestling with a situation she would have once considered unimaginable, until it became the substance of her life. “How do you react to a cancer diagnosis at age twenty-two?” she wonders. This question functions as lodestar, something of a guiding light. “With my bald head, pallor, and port,” she admits, “illness became the first thing that people noticed about me. … But for me, for all patients, the end goal is eventually to leave the kingdom of the sick.”

But how does this happen? And what does one do after it has? The key is not so much recollection but reconciliation, which is part of the intention of the memoir. What, though, does reconciliation really mean? How do we put a piece of our lives away? “Moving on,” Jaouad reflects. “It’s a phrase I obsess over: what it means, what it doesn’t, how to do it for real. It seems so easy at first, too easy, and it’s starting to dawn on me that moving on is a myth — a lie you sell yourself on when life has become unendurable.” By way of illustration, she bifurcates her narrative, framing the memoir in two parts —the first involving the experience of her illness, and the second detailing its often unsteady aftermath.

Jaouad’s point is that we never fully get better, just as we were never fully well in the first place. Life and death, health and sickness … they overlap and blur together in the singular experience of the now. To highlight this porousness, she reveals how cancer changed her family dynamics. Her mother, an artist, worries over the past: “When you were a baby, I used to take you to my studio and I painted with you strapped to my chest. … Is it possible that exposure to the paint fumes caused this?” In the present, meanwhile, the disease profoundly transforms Jaouad’s relationships; some friends stop coming around while others rally behind her. Her boyfriend is her staunchest ally — until he can’t take it anymore.

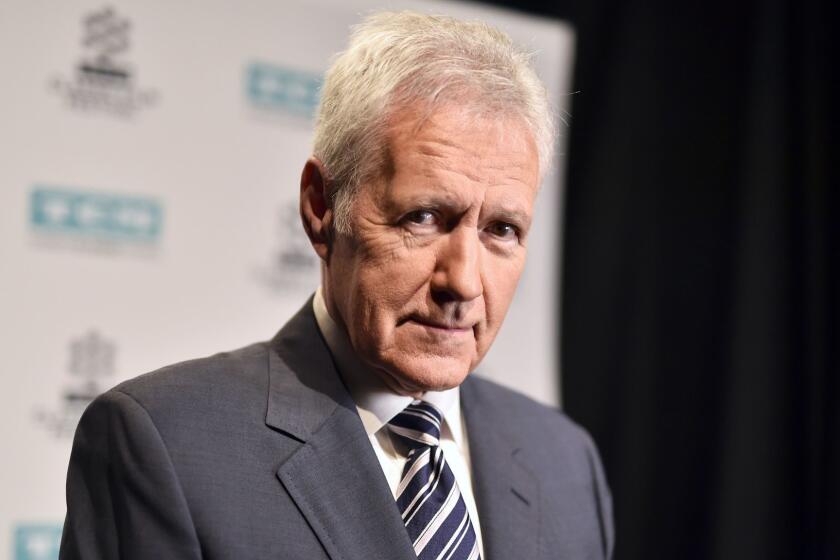

Alex Trebek is happy being an uncle figure in your life, and he’s not afraid to describe cancer’s personal toll. He sits down to talk about his memoir, “The Answer Is ... Reflections on My Life.”

She writes most movingly about her fellow travelers, the friends she made (and lost) in treatment: the poet Max Ritvo, dead at 25 from Ewing’s sarcoma; her artist friend Melissa, who “raged as death grew more imminent. ‘I’m not ready,’ she’d say.” Late in the book, Jaouad carries a vial of Melissa’s ashes to sprinkle at the Taj Mahal. “Taking Melissa’s ashes to the place she loved most doesn’t lessen the pain of losing her,” she writes, “but it has shown me a way that I might begin to engage with my grief.” Reconciliation, in other words — but of the most clear-eyed variety, with no illusions about what may be preserved.

What Jaouad is addressing is guilt and desolation; it is the experience of being left behind. “Grief is a ghost that visits without warning,” she writes. “It comes in the night and rips you from your sleep.” But “Between Two Kingdoms” is also about the struggle to remain a participant in one’s own life. Jaouad makes that explicit by shifting to present tense in the second half of the book — the part about recovery — as she travels the United States, visiting the people, many of them readers of her blog, who offered her solace during the years she was sick.

It’s a bold move, this tonal shift, and at times it can be jarring. Yet this is also, I think, part of the point. Jaouad is writing about a process, a back-and-forth. In the tension between health and sickness, past and present, a new balance must be forged. “There is no restitution for people like us,” Jaouad acknowledges, “no return to days when our bodies were unscathed, our innocence intact. Recovery isn’t a gentle self-care spree that restores you to a pre-illness state. … It is an act of brute, terrifying discovery.”

The path to Porochista Khakpour’s memoir “Sick” was not easy.

Ulin is the former book editor and book critic of the Times.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.