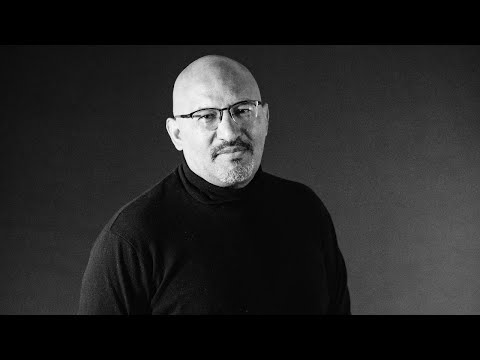

Author Roberto Lovato talks immigration and family secrets

- Share via

Roberto Lovato says he decided to write a book about his parents’ homeland of El Salvador after visiting an immigrant detention center in Texas.

That’s where he met a woman and her 6-year-old son, who shared a drawing of a white moon, blue clouds and stick-figure people. The boy said it showed how he hoped to live in the United States. Then he showed Lovato another drawing: one of a skull with razor-sharp teeth. It stood for life back home in El Salvador, where a gang shot his uncle through the teeth.

That 2015 encounter set the San Francisco journalist on a quest to explore his own family history and Salvadoran heritage.

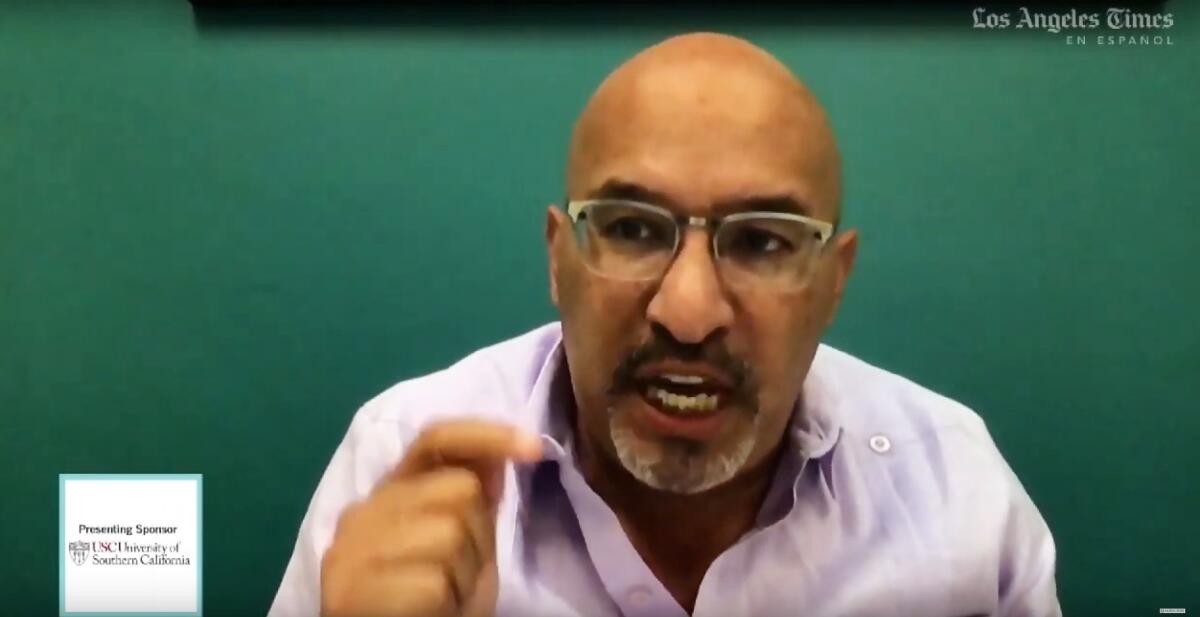

“These stories aren’t getting out there,” Lovato said Thursday during a Los Angeles Times Festival of Books virtual event. “There’s a superficial narrative.”

In September he published his debut book, “Unforgetting: A Memoir of Family, Migration, Gangs, and Revolution in the Americas.”

Lovato joined Times reporter and fellow Salvadoran Esmeralda Bermudez Thursday night for a wide-ranging conversation about family, identity and the lack of diversity in the publishing industry. “I want to be a poet warrior,” Lovato said. “I want to do like Barry Manilow but radical.”

In his memoir, Lovato entwines his experiences growing up in San Francisco in the 1970s and ’80s with his Salvadoran father’s traumatic history.

Lovato writes about state violence, gangs and the immigration crisis in the United States and El Salvador. He dives into politics and personal experiences, all while examining the history of struggle of his parents’ native land.

“I’ve always been curious about my family secrets,” he said. He described his father Ramón, 98, as a complicated man who grew up in poverty in El Salvador, conducted business in the black market and learned to survive by repressing traumatic memories of violence. “My dad also had this astonishing secret of what he lived through that he never said anything about,” he said.

After years of inquiring and researching, Lovato said he became “the memorial candle in my family that tried to light up the past, the darkness so that I could find what Carl Jung called ‘the gold that’s in the dark.’

“And I think, for myself at least, I did. Because I found the beauty and power and resilience of the Salvadoran people, and that rescued me from my previous self.”

As a young man, Lovato was studious but angry. He went on to study at UC Berkeley and became interested in the history of El Salvador.

Years later, when Lovato finished the draft of his memoir, he began to strategize how he could attract the attention of publishers while maintaining the integrity of his work and family history.

He told himself: “‘Well, I have my story, I’m not going to compromise myself, but I am going to have to titillate the industry’ … so I titillated folks with stories of gangs, violence and things of this nature. Unbeknownst to them, that was just the dark background to tell the story of our sublime power and beauty and revolutionary sensibility,” he said.

He found an agent and an editor and recalled telling them point blank: “‘Thou shalt not tropicalize my a—.’ And it worked,” said Lovato, cofounder of #DignidadLiteraria and one of the most outspoken critics of Jeanine Cummins’ controversial novel, “American Dirt.”

“I wrote it on my own terms and then negotiated my way from the integrity of my project,” he said.

In “Unforgetting: A Memoir of Family, Migration, Gangs, and Revolution in the Americas,” Roberto Lovato finally tells the full story of his rebel life.

At the end of the hourlong book talk, Bermudez asked Lovato: “So what’s next for you, Roberto? Where are you taking the revolution next?”

He responded with a smile and said, “First thing is I’m going to be with my partner ... and we’re going to take the revolution to a nice little beach house.”

After that, he’ll focus on two book projects: He’s working on “Letters to a Young Poet Warrior,” about politics and poetry from Latin America.

He’s also writing about his obsession with the scarlet macaws found in Central and South America. “I want to tell my mom’s story in relation to this bird that helped me fly out of the depths of the profound sadness that I felt when my mom died in 2013.”

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.