How the SoCal coast inspired a legendary author’s feminist Kenyan epic

- Share via

On the Shelf

The Perfect Nine: The Epic of Gĩkuyu And Mumbi

By Ngugi wa Thiong’o

New Press: 240 pages, $24

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

At 82, Kenyan author Ngugi wa Thiong’o — a towering figure of contemporary African literature and theory — is as fiercely prolific as ever. For nearly six decades, he has been building a mountain of work that ranges from novels, plays and memoirs to groundbreaking essays on language and literary decolonization.

“I am driven to write,” Ngugi says as part of an extended email exchange. “I felt this from the very first day, in my second year as an undergraduate way back in 1961, when I announced I was writing a book and was met with derisive laughter.” That novel, “The River Between,” appeared in 1965, a year after Kenya attained independence, and quickly became a landmark for a new generation of postcolonial African writers.

In the years that followed, Ngugi’s writing would become politically charged, concerned with the awakening of Kenya’s underclass and its confrontation with oppressive, despotic regimes. “Petals of Blood,” published in the mid-’70s, was banned by the Kenyan government; “I Will Marry When I Want,” a play written in Gikuyu and performed by workers and peasants in the village of Kamirithu, got him arrested in 1977. (“Wrestling with the Devil,” his prison diary, recounts his year at Kamiti maximum security prison.)

Forced into exile, Ngugi continued to pillory “neocolonial” Africa in novels such as “Devil on the Cross” and “Wizard of the Crow,” dazzling mosaics that combine biting social criticism with magical flights of fancy. More recently, he has revisited his own fraught journey in a series of memoirs, including “In the House of the Interpreter.”

In ‘Transcendent Kingdom,’ Yaa Gyasi’s second novel, she focuses on America — its promise and peril — and on one Ghanaian American family in Alabama.

Now a distinguished professor of English and Comparative Literature at UC Irvine, his work remains engaged with his homeland in new and perhaps unexpected ways. His new book, “The Perfect Nine,” is a recounting of the creation myth of the Gikuyu people of Kenya — a quest novel-in-verse that explores folklore, myth and allegory through a decidedly feminist and pan-African lens. It is Ngugi writing in oracular mode, looking back at his country as if from a great distance of space and time.

It is fitting, then, that a sense of open vistas played a part in the book’s origin story. “The idea literally came to me as I sat on a raised ground overlooking the Pacific Ocean,” he says. “I live in Irvine, 10 minutes away from the ocean, and I always find its blue vastness overwhelming.” The epic form had been on his mind long before the inspiring moment. “I have been an avid reader of epics: Homer’s ‘Iliad’ and ‘Odyssey,’ the ‘Mahabharata,’ Virgil’s ‘Aeneid,’” he continues. “All these could have contributed to the revelation as well.”

It was a Catalan epic, however — “Canigó,” which revolves around the adventures of a young knight on sacred Mount Canigou — that got him thinking about the legends of Mount Kenya, “one of the mountains of the Moon that the ancient Egyptian Pharaohs reputedly visited to commune with God.” Mount Kenya is also where, according to “The Perfect Nine,” God showed Gikuyu and Mumbi, founders of the Agikuyu people, the magical land He was bequeathing them.

In Ngugi’s interpretation of the epic, the focus shifts to the 10 — a “perfect” version of nine — daughters of Gikuyu and Mumbi, who must choose partners from among the 99 suitors who have trekked across the continent to win their hands. (Their migrations are Ngugi’s own pan-African revision of the tale.) Together, they face a series of trials and tribulations — crocodiles, snakes, ogres, hunger and despair — to earn the daughters’ devotion.

The women, who will become the matriarchs of the ten Gikuyu clans, are fearless, wise, beautiful and completely independent. “The myth goes that Gikuyu and Mumbi had no male children,” Ngugi says. “So as I sat on that raised ground overlooking the Pacific, it just came to me: Wait a minute, since they had no brothers, that means the women had to rely on themselves to do everything. They were the original feminists, the voice whispered to me, as if coming from the depths of the ocean.”

Louise Glück became the first American woman to win a Nobel Prize in literature since Toni Morrison in 1993. Her work spans nearly 50 years.

While “The Perfect Nine” may seem like something of a departure for Ngugi, the book maintains his immersion in questions of African oral tradition and the politics of language. Originally written in Gikuyu and published in Kenya in 2018, the novel has been translated into English by Ngugi and embodies, in many ways, the arguments of his 1986 essay collection, “Decolonizing the Mind.” “I am gratefully humbled that the world is catching up with my fiction and theory,” Ngugi says. “I am so glad that the issues of decolonization, particularly the decolonization of institutions and even images, are being talked about everywhere. America, for instance, has never dealt with its colonization of Native Americans and the enslavement of African peoples. So ‘Decolonizing the Mind’ is also relevant here, especially now in the era of Black Lives Matter.”

Though he continues to promote writing in African languages, Ngugi is also impressed by the flourishing of African writing in English. In Kenya alone, there’s a promising new crop, including Yvonne Adhiambo Owuor and Peter Kimani, not to mention Ngugi’s own children. “It’s absolutely amazing and a far cry from 1964, the year I published ‘Weep Not, Child,’ the first Anglophone African novel in East Africa,” he says. Four of his children have published books in English: Tee (“Of Love and Despair”), Nducu (“City Murders”), Mukoma (“Nairobi Heat”) and Wanjiku (“The Fall of the Saints”). “My own family has become one of literary rivals,” he jokes, “competing for space on our shelves.”

Ngugi has been translated the world over and celebrated with multiple prizes and honorary degrees. After a lifetime of struggle — imprisonment, exile, political isolation — Ngugi has come to occupy a central, even canonical role in African writing. He is spoken of as a perennial contender for the Nobel Prize — an honor he knows would represent something larger than himself: He would be the first East African and only the second Black sub-Saharan laureate. (Nigerian Wole Soyinka won the Nobel in 1986.) But it would also be an acknowledgment of his work in Gikuyu. “Such an award would obviously help draw attention to African and other marginalized languages of our globe,” Ngugi says. “But I have also said how grateful I am for all the Nobels-of-the-hearts that I receive daily from all over the world, wherever my books are read.”

Though the Nobel committee passed him over again in 2020, Ngugi carries on with his literary projects, nourished by both his Kenyan roots and adopted surroundings. After many years living and teaching on the East Coast, he moved to California in 2002, and has forged strong bonds here. “I loved the East Coast, but for some reason, in the West I’ve found myself thinking more and more of my homeland,” he says. “Maybe it’s the Pacific waters that remind me of the Indian Ocean, or maybe it’s that California is very mixed in terms of races and culture and reminds me of Kenya.” In any case, he is just as driven as he was in 1961. “I was born to tell a story, and I will continue telling it for as long as I have the strength to press a key on the laptop.”

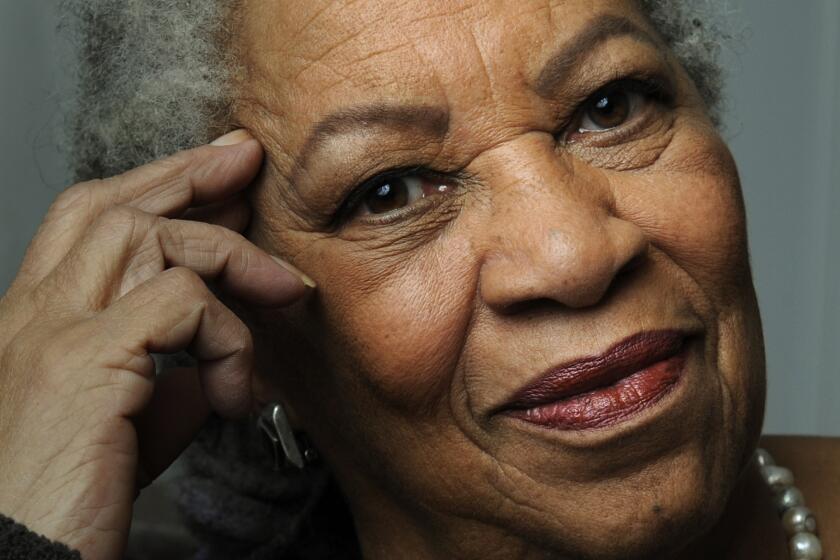

Toni Morrison, the author, essayist and winner of Nobel and Pulitzer prizes, famously encouraged would-be writers to take action.

Tepper has written for the New York Times Book Review, Vanity Fair and Air Mail, among other places.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.