Review: The man who may have loved Lucy: A novelist imagines a love affair for Lucille Ball

- Share via

Shortly before it wrapped for good last spring, “Will & Grace” dedicated an episode to the ’50s sitcom “I Love Lucy.” The homage crashed against 2020 with a dissonant clang. The tropes the show traded in were canceled ages ago: the ditzy housewife, the Latin lover, the prudish separate beds. So the “Will & Grace” cast camped up their reboot with drag and irony. A modern tribute to “Lucy” must be run through a filter of knowing satire.

But if the conceits of “Lucy” are outdated, Lucille Ball’s brand of physical comedy is deathless: A thousand years from now we’ll still laugh at her, chipmunk-cheeked with chocolates and tanked on Vitameatavegamin. That certainly comes across in Darin Strauss’ ingenious and bittersweet fourth novel, “The Queen of Tuesday.” The author of the similarly timeless historical novel “Chang and Eng” positions Ball not as a contemporary figure, exactly, but somebody a contemporary reader can relate to: heartsick, flawed, wounded by the public glare but determined to triumph over the haters. A second-wave feminist avant la lettre.

For the record:

5:17 p.m. Aug. 19, 2020“This article refers to network skittishness over airing a show about Lucille Ball and Desi Arnaz as a mixed-race couple. Though this might have been a common perception at the time, Arnaz was Cuban American and white.”

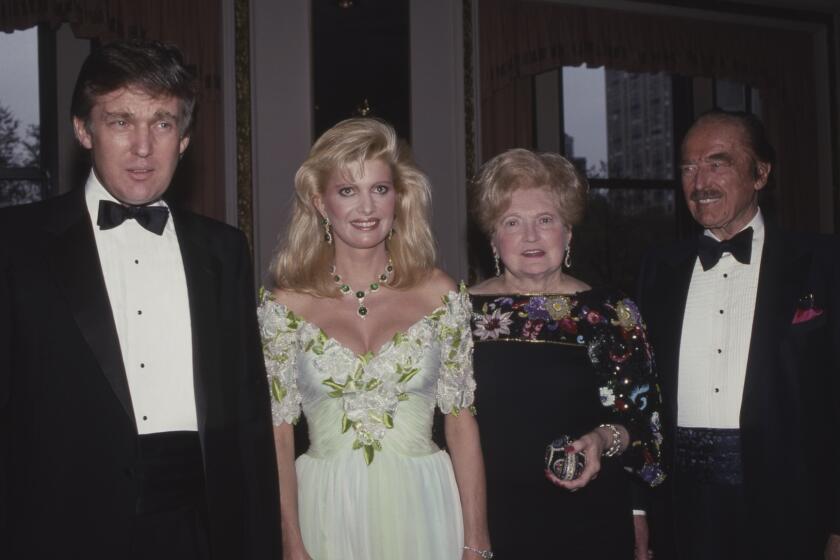

To better stress her relevance, Strauss finds a way to work in a Trump. We open on Coney Island, 1949, as the president’s developer father, Fred Trump, hosts a party on the beach. He’s clearing the way for a new project by removing an old one — a glass-enclosed amusement park called the Pavilion of Fun. Ball, her husband, Desi Arnaz, and other fancy guests are handed ceremonial bricks and invited to fling them at the doomed structure.

The President’s “only niece,” clinical psychologist Mary Trump, portrays a man warped by his family in “Too Much and Never Enough.”

Glass houses, glass ceilings, shaky ground, obsolete entertainment: The novel’s opening pages are fit to burst with metaphors for Ball’s predicament. Before “I Love Lucy,” she was a vaudevillian and out-of-work film actor barely hanging on to Hollywood’s B-list. “Lucille Ball was handy with a joke in ‘Stage Door,’ but she is no Groucho Marx,” Strauss writes. “Lucille Ball hula’d her hips in ‘Dance, Girl, Dance,’ but she is no Carmen Miranda. Lucille Ball held a tune in ‘Hey Diddle Diddle,’ but is she an Ethel Merman? No, she is not an Ethel Merman.” She has an idea for a TV show, but the network and sponsors are skittish about using the nascent medium to air a comedy about a mixed-race couple.

Ball’s career anxieties are paired with more intimate ones. That night on the beach, she meets an aspiring writer and young real estate developer named Isidore Strauss. They flirt, he steals a kiss; Arnaz slugs him. But a spark between Isidore and Lucille persists. And here’s where things get a little more 2020: Isidore was Darin Strauss’ grandfather, and though he has no evidence of an affair, this autofiction-ish novel convincingly imagines one. The fling would’ve been an escape hatch for Ball, who was frustrated with the media glare, her philandering husband and a brief but terrifying interaction with the House Un-American Activities Committee.

Isidore had frustrations to escape as well: thwarted literary dreams and a just-so existence in a Long Island Jewish enclave. “A wife, material comfort, a slice of pie after dinner,” Strauss writes from inside his grandfather’s head. “If these are all you get, what is the point of being born into this adventurous century?”

Even in Strauss’ imagination, Isidore and Lucille’s affair was just a matter of a couple of trysts. But it did result in a collaboration: a film treatment about a Black Civil War soldier. This treatment actually exists, and interludes in the novel feature Strauss himself attempting to sell an agent on the project in the ‘90s, uncertain of the pair’s relationship but figuring it could be a selling point. There’s a gentle frisson between the ’90s Darin who romanticized Isidore’s ambition and the older one writing this book now, who sees mostly missed opportunities in his grandfather’s life.

“A Star Is Bored,” by Byron Lane, may not dish all the dirt on the world of assistants, but it’s highly entertaining and surprisingly tender fiction.

But Darin takes a while to insinuate himself into the story, which makes “The Queen of Tuesday” feel somewhat off-kilter. Rather than a historical novel leavened and complicated by the novelist’s presence, the book often feels divided into segregated lumps of “auto” and “fiction.” A reader looking for a straightforward historical novel about Ball’s life might be thrown by its escalating gamesmanship. But even someone who grasps what Strauss is doing and likes it might wonder whether a novel about a comedian should be funnier. A set piece about Ball filming what would become the first “I Love Lucy” episode studies her thoughts and actions so fussily that her objective — to make people laugh — is all but lost.

Strauss finds his footing toward the end, balancing Isidore‘s and Lucille’s real lives and the romance he’s dreamed for them. In either scenario, they were kindred spirits: Isidore wanted to buck convention through Ball, who was ironically doing the same thing through her very conventional sitcom. Both craved domesticity, but with different partners.

Strauss captures the way Arnaz’s cheating made Ball quietly vengeful, all the more eager for Isidore’s attentions: She became “simply one more woman swallowing down an injustice; if suppression were torque, Lucille could lift the Sierra Nevadas right over her head.” As he shuttles between their later lives, Strauss isn’t straining so earnestly to connect them; he seems to genuinely lament a love affair that never happened.

In Emily Beyda’s debut novel, “The Body Double,” a woman is hired to replace a fallen star.

Ball was a success: She became the rare female head of a large studio in her era, divorced Arnaz and died a legend in 1989. Isadore was less successful: He struggled with both love and money before his death in 2000. If the two indeed had a fling, as Strauss imagines, it was a fleeting and damaging one, leaving two families mired in resentment and alcohol. That’s Strauss mirroring reality, which is part of the novelist’s job. But Strauss also dreams of a scenario in which the romance might have worked, which is a novelist’s job too. “Wouldn’t it be a perfect gift to my grandfather if I could write that and have it be true?” he asks toward the novel’s conclusion. It’d be a perfect ’50s screen romance. But Strauss knows what time we’re living in.

Athitakis is a writer in Phoenix and author of “The New Midwest.”

The Queen of Tuesday

Darin Strauss

Random House: 326 pages, $27

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.