The summer’s best novel about the bankrupt American Dream

- Share via

If you buy books through links on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

A few years ago, one of my beloved professors invited me back to my alma mater to give an informal talk to English majors about working in book publishing. Their wide-eyed (mostly female) faces are forever emblazoned in my memory. I tried to impress upon them that unless they have a plan for financial assistance — parents, roommates, odd jobs — it is virtually impossible to pay rent on an entry-level publishing salary.

They stared back at me. “But,” one brave soul ventured, “are there other publishing jobs outside of New York?” Sure, I reassured her. The other heads at the table nodded in unison.

Lynn Steger Strong is a writer and a teacher who lives in New York. Her incredibly smart column for the Guardian lays bare, through her own experience, how precarious life can be even for people with certain privileges, especially during a recession and a raging pandemic. My personal favorite is headlined, “A Dirty Secret: You Can Only Be a Writer if You Can Afford It.” Strong and I spoke recently by phone; as writers and mothers without childcare, we reached an immediate understanding. “I’m hanging laundry on my fire escape because we’re having issues in our building and avoiding the laundromat because of COVID,” she said with a sad, exasperated laugh.

The occasion for our talk wasn’t nonfiction, but rather her new novel, “Want,” a story about motherhood, disappointment, financial disaster, regret and loneliness that book Twitter has been raving about for months. Elizabeth is a teacher in New York with two young daughters. When the novel begins, she and her husband are about to declare bankruptcy. Elizabeth is looking for a way to disappear as she reconnects with Sasha, a friend from childhood — a pursuit that turns out to be more grounded in guilt than envy. The narrative is as much about “anxiety as it is about precarity,” as Strong said.

Elizabeth talks about the lack of a safety net with poetic candor. “What’s it like,” she wonders about a wealthy young woman she encounters, “to have pain in your teeth and then go get them fixed instead of waiting it out until you’re pretty sure the nerve has died since you don’t feel it any longer?” Her own two root canals were followed by a “ten-thousand-dollar manmade tooth.” The hospital debt from her C-section is $30,000, and then there are the children. “We were ordering too much takeout because we were both working and trying not to pay for childcare.” As Elizabeth puts it, “My body almost single-handedly bankrupted us.”

Elizabeth’s story unfurls in a series of short scenes, almost like beats in a play. “This book is very strange,” Strong said. “I wrote the draft really fast, in a period of eight weeks when my kids were in school. I have since found sentences that were verbatim in the novel as much as a year and half earlier in my emails. I believe that writing is work, but that part feels a little like magic.” To readers it might feel like prophecy — or the surfacing of something invisible. “Want,” like our current crisis, exposes a system on the verge of collapse.

#PublishingPaidMe shows, in part, how arbitrary book advances are. But that guesswork isn’t the problem; it’s the executives doing the guessing.

Elizabeth’s narrative brims with the kinds of observational details we’ve come to expect from autofiction, which blurs the line between narrator and author. But despite its roots in Strong’s experience, “Want” is a traditional novel in the sense that Elizabeth is a fully developed character with her own distinctive journey.

“I’m wary of arguments,” Strong said. “If I made the same social arguments, even to my close friends, everyone nods their heads. But what do these things feel like? What does it feel like not to have a safety net? How do you feel it in your bones? I feel fiction in my bones.”

Elizabeth’s parents are no help to her in any sense of the word. Her father tells her that giving her money would be like “throwing it away.” Her mother threatens to call child services: “They’ve suggested I’m not equipped to be a mother.” When she realizes she has no other option, she finally calls them to ask for money. “At what point, says my mother, is it time to cut your losses? At what point is it time to give up on this whole dream thing?”

“What dream?!” I wanted to scream at the page. The dream of working hard at a job you love, paying your bills, taking care of your family and knowing that a health crisis or student loan won’t sink you into poverty?

“What dream?” Elizabeth responds.

This is not the kind of novel Strong originally saw herself writing. “When my first book was published,” she said, “I was trying to write a book as novels are supposed to be — they are supposed to be about wealthy white people. And then when the book came out, I was embarrassed and ashamed. So I began to read more widely. I wanted to write a novel that hadn’t been written before.”

For all of Elizabeth’s struggles, neither she nor the reader ever forgets her privilege. The other teachers at Elizabeth’s school are Black. “They don’t know that we pay extra rent to live in a neighborhood we can’t afford so that our kids can go to a school that’s said to be better than the one my co-homeroom teacher’s kid will go to.” Her students are referred to as “underserved.” They are Black. Though Elizabeth frequently skips out on the job in the middle of a school day, she’s sure she won’t get fired. “I’m a thirty-four-year-old J.Crew-cardigan-clad white woman with an Ivy-League Ph.D.” The “CEO” that runs the school “reports back to the principal that she likes the feel of me.”

Memoirs by Kiese Laymon and John Edgar Wideman; essays by Darryl Pinckney and Mikki Kendall; masterpieces from Michelle Alexander and Claudia Rankine.

Strong is conscious of the buffer that whiteness affords, especially in 2020. “Your skin tone and your education can function as money to some extent when the world is burning,” she said. “A good amount of the people that I know have an escape hatch. They’re scared and sad and empathetic, but they have an escape hatch.”

There is a homicide alluded to in the novel that did actually occur in 2011. I asked Strong why she included it in Elizabeth’s story. “She tells the story to someone else, which is this strange thing we do when we carry around violences that belong to someone else.”

As Strong spoke, I thought of all the videos of racial violence on social media over the last few weeks: George Floyd pinned to the ground; the screaming faces of protesters being beaten or tear-gassed; Ahmaud Arbery fighting for his life; the audible pain in the voice of the woman filming the killing of Rayshard Brooks. I carry these violences, but they don’t belong to me. “Elizabeth has to deal with this episode of extreme violence, and it certainly affects her,” Strong said. “But as a white privileged woman ... how quickly her life just goes on.”

Walter Mosley, Luis Rodriguez, the coiner of #BlackLivesMatter and others sketch a hopeful future for L.A. and the U.S. after George Floyd protests.

This past month has seen violence in the streets and, on pages like this one, the proliferation of lists aimed at educating readers through nonfiction. Books like “Between the World and Me” and “How to Be an Antiracist” are flying off the shelves, and rightly so. But fiction can also play a role, whether it forces a reader to confront the struggles of others or to think more deeply about what blinds us.

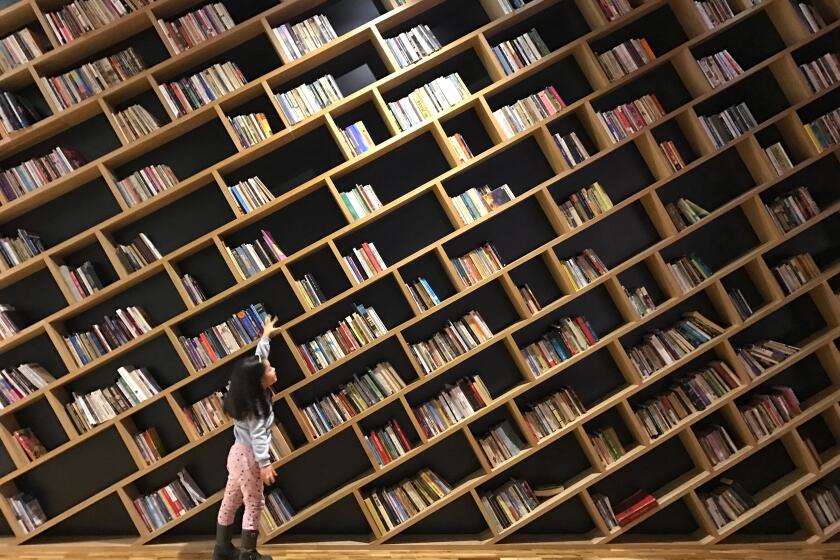

What’s it like to feel there’s no safety net? You might consult Edith Wharton. What’s it like to feel trauma? You might read Virginia Woolf. What’s it like to feel racial violence? It might not belong to you. Read Toni Morrison. In the beginning of “Want,” Elizabeth says, “there was a time I thought giving books to other people — showing them their richness, their quiet, secret, temporary safety — could be a useful way to spend one’s life.” “Want” may be about the realistic limits of that kind of solace or the kind of life it can afford you. But it’s also powerful proof that novels, and novelists, can still speak undeniable truths.

Ferri’s most recent book is “Silent Cities: New York.”

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.