Michael Connelly on ‘fake news,’ COVID-19 writing and his nonprofit-set thriller

- Share via

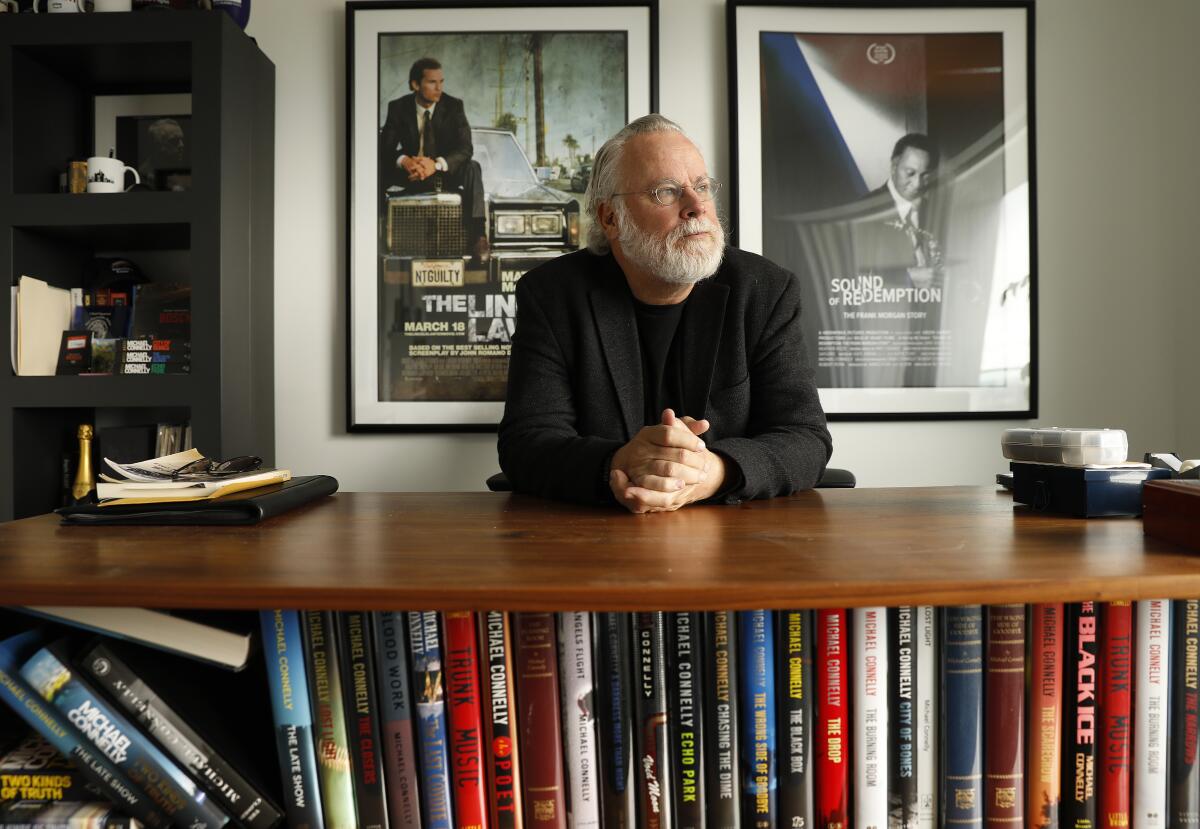

With more than 74 million books sold worldwide, former Los Angeles Times reporter Michael Connelly has created not just a collection of mysteries, but a culturally pervasive alternate reality as well — the Michael Connelly Universe, with its own super-group of crime-fighting heroes. Thanks to the books and screen adaptations, Harry Bosch and criminal defense attorney Mickey Haller (“The Lincoln Lawyer”) are the best-known members of the MCU. But newspaper reporter Jack McEvoy is just as significant, not least because he was the first non-cop to join Connelly’s stable.

For more than two decades, McEvoy’s adventures on the job have offered an insider’s view of the evolution of the newspaper industry. “The Poet” (1996) mined the struggles of a real-life regional newspaper, the Rocky Mountain News. By 2009’s “The Scarecrow,” McEvoy had moved to the Los Angeles Times during a particularly dark period of corporate control. Now, in Connelly’s latest thriller, “Fair Warning,” he works for a new kind of news-gathering organization — a nonprofit.

For many years, I’ve spoken with Connelly on panels and acknowledged his influence on my own crime fiction. This time, I caught up with him by telephone as he was sheltering in place with his family in Los Angeles, where he spends most of his time. He feels fortunate to be weathering the shutdown here instead of at his second home, in Florida, where “they don’t seem to know what they’re doing” when it comes to COVID-19. We spoke about the perils of journalism in the era of “fake news,” the future of “Bosch” in the era of coronavirus and his next book, possibly the first novel whose plot takes the pandemic into account.

FairWarning is an actual journalism nonprofit. How did it become the subject of your book?

FairWarning is one of many online investigative news sites that have emerged out of the crumbling newspaper business. It was started by Myron Levin, whom I worked with 30 years ago at the Los Angeles Times, although we had different beats. At some point, Myron took a buyout and started FairWarning 10 years ago this month. From the beginning, I was a supporter. Then I was asked to join the board.

As a novelist, I believe water seeks its own level: I had access to the organization, I knew how they operated, and I knew they had good goals. I knew the title of the news site could be a good title for a book. So I went to Myron and the board and asked for permission to use the organization as Jack’s employer.

You also used Myron.

Myron is a unique individual, very target-focused, and I realized that I’d like to capture that in the character of Jack’s boss. And so I went back to the well and asked Myron if I could build a character based on him.

I sent him the finished manuscript, and he came back with a few suggested fixes, but they were more about the procedures of the real FairWarning. He didn’t change anything about his character, which I took as a good sign.

What do you miss most about being a journalist?

Probably the camaraderie in the newsroom. It’s definitely not the product because I’m still writing crime. I know it’s classified as fiction, but there’s a certain reality to it, there’s research that goes into it, there’s the idea of getting it right, just like when I was a reporter. So I still get those kinds of fulfillments, but it was great being in the newsroom with people.

That camaraderie comes across in “Fair Warning” and the other McEvoy novels. But there’s something about McEvoy that nags at me. Maybe it stems from his motto, “Death is my business,” and the moral and ethical lines he comes close to crossing to get the story.

I think that’s how you deliver or delineate characters, the kind of moral questions they confront — how far they can push that line, and what are the consequences? [As a reporter,] you were constantly coming up with issues like that, where just naming somebody in a story can put people in danger. That was part of that world, and you had to be really careful. I take that into consideration in what Jack does. But at the same time, it’s a character-driven entertainment medium. I think characters who push the line — maybe go over lines or maybe put one foot over but don’t take the second foot over — they’re very interesting to read and therefore more interesting to write about.

Among other issues, “Fair Warning” is about journalism being threatened by politically motivated attacks on “fake news.” Why was it important for you to tackle that?

Reporting is a very difficult job to do right. My sympathy for and understanding of that have only been accelerated in the last few years, where you had the added dimension of this ongoing kind of blind slandering of the motivations behind journalists. I haven’t been a reporter since the early ’90s, but even then it was pretty tough. Yet most of the time people understood what your job was, and that you were an extension of them, of your community. Nowadays there’s this wedge jammed into that relationship where certain forces in the world are trying to say that it’s not a noble pursuit and that there is some kind of ulterior motive. … It just makes a tough job tougher. And that was why, sometime last year, I said it’s time for me to write about Jack McEvoy. It wasn’t like I wanted to write about digital or genetic stalking or anything like that. I wanted to write about a reporter who’s undaunted and fierce in trying to find the hidden truth.

Is it true that the seventh season of “Bosch” is going to be the last?

It looks that way. You never know what’s going on with COVID-19 and how that will interrupt production. In a perfect world, Amazon could say, “Hey, we might need more than one more season,” but as of right now we’re writing what is the last season. I’m writing with Eric Overmyer what is going to be the last episode. And we’re wrapping it up as if it’s the end of the show.

Your work in TV goes back some 20 years. What was it about television that attracted you as a creative person?

I wasn’t really that attracted to it for at least a decade of my writing life. But TV changed, it became more novelistic when it branched into cable and then streaming. So this serialized storytelling makes cable and streaming the closest thing to novels that I think is out there.

Obviously the pandemic has affected production, but what about the process of crime writing? Have you thought about what it’s going to be like, researching those books or even writing about the obstacles your detectives might encounter while investigating crimes?

In a way I have, because I have a “Lincoln Lawyer” book coming out in November [“The Law of Innocence”]. I try to make my books very contemporary, and so it was actually set in April of this year. Then the virus happens, and we just don’t know how we come out of this. So what I ultimately did was back the story up. So rather than it starting in April, it now starts in December 2019 and then moves into this year and the first part of this crisis. If you’re going to write a contemporary novel that’s realistically reflecting the world, you’ve got to put [COVID-19] in there, but it’s hard when you don’t know the outcome. We don’t know anything yet. Therefore it really does hinder the creative process, at least for me.

Woods is a book critic, editor and author of several anthologies and crime novels.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.