‘Stealing Home’ revisits Dodger Stadium’s nefarious origins

- Share via

In Chavez Ravine, this would normally be a time for baseball. Barring the 1995 MLB season, which was shortened due to a strike, this is the first time since 1961, the year before Dodger Stadium opened, that the arrival of spring in Los Angeles hasn’t been heralded by the roar of 56,000 fans, some of them gleefully playing hooky. For now, the stadium remains gated and eerily quiet. It’s as if it’s not even there.

The author Eric Nusbaum has been imagining a world with no Dodger Stadium since he was a junior at Culver City High School in 2002. That was when an older man named Frank Wilkinson showed up to give a guest lecture to Nusbaum’s history class and said, “Dodger Stadium should not exist.”

“I remember at the time being blown away,” says Nusbaum. He is taking a video call in a closet, his “little sanctuary of book promotion,” as he waits out the COVID-19 pandemic at home with his wife and children in Tacoma, Wash. “I was the kind of kid who read the sports page every day. Maybe because I was such a big Dodger fan, I had willfully ignored it.” What he means is the dark history of the land where the stadium sits, the subject of his new book, “Stealing Home: Los Angeles, the Dodgers, and the Lives Caught in Between.”

“Stealing Home: Los Angeles, the Dodgers, and the Lives Caught in Between” examines the lives forever changed by the building of Dodger Stadium.

The story has roots in Wilkinson’s tenure as a public-housing official in the early 1950s. He was one of the central players in the bureaucratic nightmare that was Elysian Park Heights, a failed housing project initiated in Chavez Ravine.

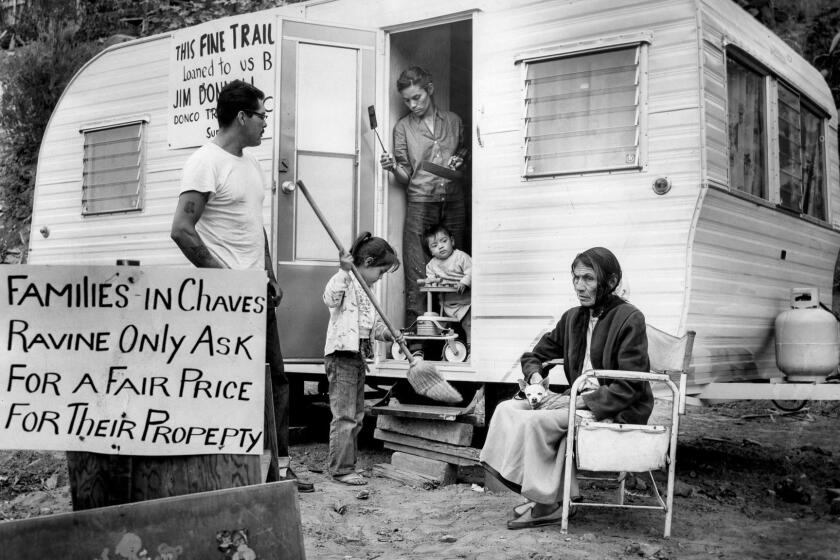

Eminent domain was used to serve evictions, offering measly compensation, across three largely Mexican American neighborhoods in the hills above Echo Park — Palo Verde, La Loma and Bishop. After Wilkinson was fired for Communist associations during the Red Scare, the project went down with him. The mostly cleared-out land sat in limbo for years before an all-American solution was found: Walter O’Malley and his Dodgers needed a new home.

“Stealing Home” is a scrupulously detailed account, written in novelistic, economical prose and featuring people like Wilkinson and O’Malley but focusing on those “lives caught in between.” Mostly it’s about the Aréchiga family, who became symbols of “the Battle of Chavez Ravine” when photos of them being forced out, some literally kicking and screaming, were widely circulated. They sat across the street and watched in horror as the city bulldozed their hand-built family home of nearly 40 years.

Now almost 60 years in the past, this chapter of Dodger history becomes less tangible every season. Angelenos might have seen the 2003 Culture Clash play “Chavez Ravine” or stumbled across Don Normark’s 1999 book of photos, “Chavez Ravine: 1949,” but it just doesn’t come up all that often. Today, Dodger fandom is one of the few civic identities that unify almost all demographics, and the stadium, with its cotton-candy sky good enough to eat, as Vin Scully would say, offers a magical oasis of tranquility right in the middle of the city.

“I don’t think that it’s that fun to go to a Dodger game and tap your neighbor on the shoulder and say, ‘There used to be a neighborhood here,’” Nusbaum says. “It’s a hard thing to be able to hold both the joy of Dodger baseball and the tragedy that preceded it in your heart at the same time.”

Nusbaum and I had planned to tour points of interest related to the book. But after his press trip to L.A. was canceled he provided an annotated driving tour instead: a stretch of homes on North Boylston Street, by the stadium’s Scott Avenue entrance; the Police Academy; the Elysian Park Recreation Center; the Historic Mission San Conrado.

On Boylston sits a tiny residential patch that was spared from development, which makes it possible to imagine what the other communities might look like today. Winding up away from the stadium toward Academy Road, these few holdouts vary from modest starter homes to upscale bohemian playgrounds, not too different from contemporary Echo Park. By the Police Academy is a vestigial half-block of Malvina Avenue, the Aréchigas’ old street. (Their home would’ve been somewhere near the northern edge of the stadium parking lot.) Envisioning sprawling, vibrant neighborhoods in these spots is an almost brutal what-if exercise.

But Nusbaum’s history is more than just a nostalgic paean or a jeremiad; the history of public housing and so-called “slum clearance” is too tangled for that. Nusbaum is mindful of the fact that it was the city, not the team, that kicked the families out. And the city’s initial intentions were ostensibly noble.

“It is the conundrum,” says Jan Breidenbach, a professor at Occidental College who teaches the episode of Chavez Ravine and knew Wilkinson before his death in 2006. “Do we leave people to live in slums? Or do we do something to build housing for people who need it? I fall on the side that shelter is a public good, and it’s a public responsibility. … But I cannot tell you how upset I would be if they took my house.”

Some have taken issue with the idea that these neighborhoods were slums. It is true that the neighborhoods weren’t well equipped with proper plumbing and paved roads, but that was largely a result of the city’s own neglect. And the legacy of housing projects initiated back then is mixed at best; by most accounts, more units were torn down than built.

In any event, Nusbaum keeps the book’s focus personal. “Ultimately, [the Aréchigas] were real people who did a lot of really difficult and amazing things to make a life for themselves and for their family,” Nusbaum says. “What happened is that the government took their home, sold it to a private enterprise, and then kicked them out of it. … And the fact that they were immigrants is probably a big part of why that happened to them.”

In 2000 Bob Graziano, then-president of the Dodgers, extended literal olive branches to members of the three neighborhoods and their descendants, whom he praised for “not forgetting the past, but forgiving the past.” Since that time, however, the team hasn’t made continuing efforts to acknowledge that past. On the “stadium history” section of the Dodgers’ website, history simply begins with the park being “carved as it is into the hillside of Chavez Ravine.” (The Dodgers did not respond to several requests for comment regarding this story.)

“I think the Dodgers should apologize,” says Nusbaum. “I think the city should apologize. I think the county should apologize. I think all three entities should work with members of those communities and their descendants on some sort of formal way to make amends.”

One such descendant, Edward Santillan, has found a way to move on. His father, Lou, was born in Chavez Ravine (Lou claimed that his umbilical cord was buried beneath third base), and never forgave the team. But Edward didn’t let that stop him from becoming a fan. He’s also worked for the city for decades, supervising a parking garage at City Hall. (Nusbaum included City Hall in his driving tour.)

“I can’t see myself rooting for the San Francisco Giants or whatever,” Santillan says. “It’s gonna be my home team.”

Before his death in 2014, Lou Santillan organized an annual reunion for Los Desterrados — “The Uprooted” — at the Elysian Park Recreation Center. Edward has since taken an active role in maintaining the event.

“It’s the newer generations that have sparked an interest in Chavez Ravine,” Santillan points out. He says younger people have started attending the reunions, interested in learning more about what Palo Verde, La Loma and Bishop were like. “But at the same time the Dodger blue tradition continues. It’s a mixed feeling.”

Santillan has two young daughters and he takes them to games, where he tells them the story about his father and grandparents and the umbilical cord beneath third base. “You get older,” Santillan says. “Things start coming into perspective. It all makes a full circle.”

Rogers is a writer and editor in Los Angeles.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.