- Share via

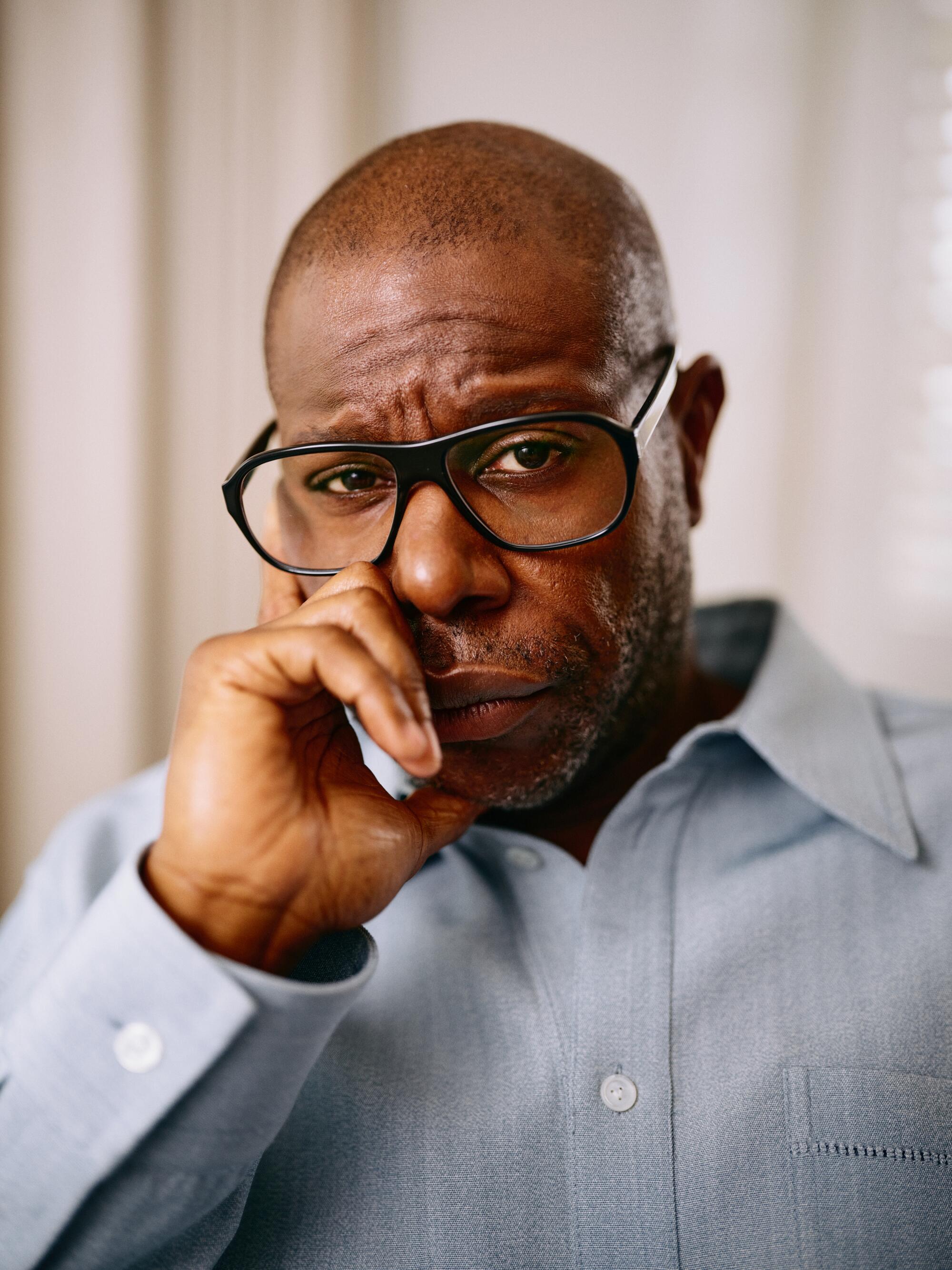

For British director Steve McQueen, the past isn’t worth dramatizing unless it can illuminate the present, so when he makes films steeped in history — whether it’s “12 Years a Slave” or his World War II epic “Blitz” — he’s asking audiences to judge where we are now in relation to what’s happened before.

“You measure yourself on where we’ve been, where we are and how far we need to go,” says McQueen. “It’s also, for me, who’s left out of these stories, and who has the upper hand to tell these stories.”

It’s why “Blitz,” set in London during Nazi Germany’s cataclysmic bombing of the city, centers on the perspective of a munitions factory worker (Saoirse Ronan) and her mixed-race son (newcomer Elliott Heffernan), rather than a man on the front lines or in the corridors of power. While conducting research for “Small Axe,” his 2020 anthology of films about resilience in the city’s West Indian community, McQueen had come across a photograph of a Black boy on a train station platform awaiting evacuation during the Blitz.

Directed by Steve McQueen and featuring Saoirse Ronan, the vividly mounted WWII film tries an unusual tack into an era that is often celebrated without question.

“I thought, ‘That’s an in,’” he recalls. The picture inspired the tale about young George Hanway’s journey home after jumping the train, encountering aspects of British society — positive and negative — along the way. “We confront things through his eyes,” he says. “It’s not ‘Oliver Twist.’”

George’s single mom makes bombs and tries to do best by her bullied son and her father (Paul Weller), who lives with them. McQueen wanted to show who women really were then, outside of the classic representations of loved ones waiting and crying. The research bore that story out too. “You’ve never seen these images before, where women are the physical and emotional backbone of the war effort,” he says. “They were supplying ammunition, looking after elderly parents, evacuating their kids.”

McQueen saw “Blitz” as a story of love, with the bond between mother and child central to the tale. “Their chemistry was real,” he says of the rapport between Ronan and Heffernan, noting that the former child actor took the first-timer under her wing. “They loved playing together.” Add rock musician Weller, acting for the first time at 66, and the trio forged a formidable onscreen family and off-camera bond. “They wouldn’t stop having fun. I was thinking, ‘Goodness, I wish that was my family.’ There was no hierarchy. It was beautiful.”

When did he know Heffernan, discovered after a widely cast net for the role, was the ideal George? “Day 1, his stillness,” McQueen says. “It was a silent movie star quality. You look at him, and you want to know more. He holds your gaze.” Working with the youngster, he says, fostered a way of filming that was attuned to what Heffernan might do as much as what McQueen might want. “You have to be sensitive, because he has that energy of, ‘What is he looking at? How is he reacting?’ Sometimes, as a director, you’ve got to get out of your own way. You feel it, smell it, allow it to happen.”

Diligent research went into every aspect of “Blitz,” from the actual song being performed at the swanky Café de Paris when it was bombed to the harrowing flooding of a subway station, to a scene in a shelter depicting a protest against bigotry that stemmed from a real incident. But the movie reflects elements of McQueen’s life too. The original song “Winter’s Coat,” sung by Ronan’s Rita at her factory for a radio broadcast, is a nod to his late father.

“When he died 18 years ago, he left me his winter coat,” says McQueen, who wrote the song with Nicholas Britell and Taura Stinson. “I wanted the idea of absence and presence, where putting on the coat is like an embrace, where you’re feeling the warmth of that person’s body.”

The Oscar-winning director’s complicated relationship with Britain informs his latest film, which follows a mixed-race boy during the bombing of London.

Nothing was more personal, however, than George’s decision to jump from a moving train bound for an unknown destination. “His narrative was laid out for him, but he defied it, and it changes his life, and that’s what happened to me,” says McQueen, who as a schoolboy experienced the kind of institutional racism that could have marked his life for failure if he’d let it. “Everything is, in some ways, finding your way home, self-determination.”

McQueen remembers being taught about the Blitz in school, and its importance to Britain’s sense of self. He hopes “Blitz” honors that history by widening the picture to be more truthful about who populated the nation. “A lot of our identity is based on that, it being our ‘finest hour,’” the director says. “What was our finest hour? Well, a lot of people contributed to that who have been erased from that history. They’re ghosts, and I need to illuminate them. I need to give them a platform. How could I not? The multiculturalism of London at that time, there’s an amazing complexity to that landscape, so rich, so textured and visually dynamic.

“For a filmmaker, it’s gold.”

More to Read

From the Oscars to the Emmys.

Get the Envelope newsletter for exclusive awards season coverage, behind-the-scenes stories from the Envelope podcast and columnist Glenn Whipp’s must-read analysis.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.