- Share via

Have you heard the one where Bradley Cooper does impressions of both Clint Eastwood and Sienna Miller?

During the recent Envelope Directors Roundtable, the conversation turned to rehearsal and how much is enough. Cooper recalled a moment while acting in “American Sniper” where he learned a lesson from director Eastwood about the value of knowing when not to over-rehearse.

Eastwood had explained to Cooper and his co-star Miller how the blocking of a scene would go. (Cue growly Clint impression.) Miller then walked her way through it. (Cue Miller’s charming British lilt.) Eastwood said, “All right, I’ll see you Monday.” He had shot the rehearsal and felt he got what he needed.

- Share via

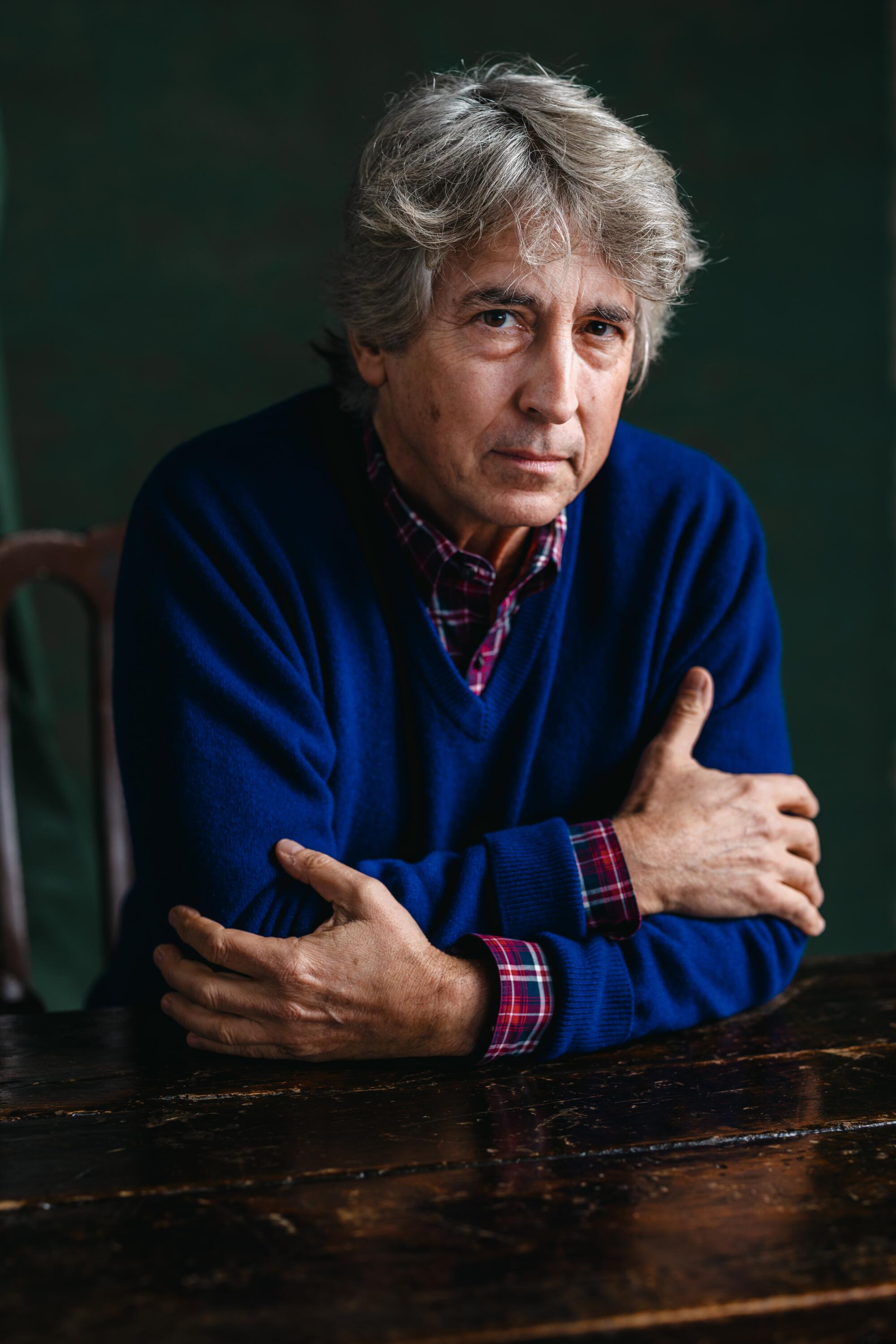

The Envelope’s Directors Roundtable welcomes directors Blitz Bazawule, Bradley Cooper, Michael Mann, Alexander Payne, Justine Triet and Celine Song.

An air of warm collegiality, friendly sharing and mutual understanding marked the Nov. 18 conversation that brought together Cooper, who directed (and stars in, produced and co-wrote) “Maestro,” with “The Color Purple” director Blitz Bazawule, “Ferrari” director and producer Michael Mann, “The Holdovers” director Alexander Payne, “Past Lives” director and writer Celine Song and “Anatomy of a Fall” director and co-writer Justine Triet.

At the conclusion of the conversation, Payne exclaimed what a surprising treat it had been.

“I gotta say, it is so fun to hang out with other filmmakers,” he said. “I mean, I know we have this, ‘Oh, promote our movie’ thing going on. But forget that, because we don’t meet one another other than that. Directors live in our individual fiefdoms. So it’s in these periods that we get to meet each other. That’s a real gift.”

Their conversation here has been edited for length and clarity.

Bradley, with “A Star is Born” and “Maestro,” you’ve now made two portraits of artists and how they balance their work and their life. Are these in any way self-portraits? How much of you is in these films?

Bradley Cooper: I mean, hopefully all of me is in these films. All we’re searching for is truth. And even cinematically, even in the composition, I hope it’s as autobiographical, as truthful, as even the acting or the subject matter. The great films in terms of what lasts — because you see a movie that sort of floored me at 12 but it’s kind of heartbreaking when you see it as you grow old. But I’ve sort of come to peace with that, it lived for a time, and it probably will for somebody else, but I do think that if it’s truthful, then actually it’s transcendent. And that’s what I’m always aiming for.

Celine, your film is rooted in something that happened to you. Is there a point where it stops being about you and becomes fiction?

Celine Song: It really did start from this one particular feeling that only I could have had. So that was kind of the autobiographical, personal thing of it, which is that moment where I was sitting between my childhood sweetheart who had come to visit me from Korea, and my husband that I live with in New York City. And sitting between them, translating between these two people, it felt like I was not just translating in language and culture, but also in between parts of my own self and my own history.

And then of course, as the movie is coming out, the initial feeling was, “Is anybody going to understand this?” And what I learn every day is that my audience is experiencing it subjectively. I think I know more about my audience as people, and their childhood sweethearts, than any filmmaker, because they all wanted to come tell me about it.

Alexander Payne: But isn’t it always the case that the more specific something is the more universal it is?

Blitz, in the musical “The Color Purple,” how do you locate yourself in that story?

Blitz Bazawule: Well, first I start with Alice Walker’s brilliant novel, right? Like that’s the holy grail for me. And then the Steven Spielberg cinematic classic, and then there’s a Tony Award-winning Broadway [musical]. So it has such a sprawling world that is already created. It’s deeply emotional. It’s hallowed ground for some people. People found healing in this piece of art. And so for me the way I came to it was, “What am I going to contribute?”

And if I have nothing to say, I back off quickly. And it wasn’t until I went back to Alice’s words and the opening of her book is, “Dear God, I’m 14, can you let me understand what’s happening to me.” And I went, “Whoever’s writing letters to God has an imagination.” People who are dealing with trauma and pain are constantly in their heads, trying to work their way out of it. So I could find universality in that. I immediately went, “I think we can actually contribute something to this canon of work.”

Alexander, do you find that you have to emotionally connect to your characters? Do you need to identify with them?

Payne: One hundred percent. What are you, out of your mind? That’s our job, isn’t it? Especially if we write our characters, we’re already in love with them. I always think of William Wyler, and he would always say that even if he hasn’t written the screenplay, it’s the director’s professional job to find his or her way personally into the script. And he always gave the example in “The Best Years of Our Lives” when Fredric March comes home to Myrna Loy. And it’s a beautiful scene where she’s in the kitchen and her back is to the front door and Frederic March returns after five years away at war. And the kids open the door and she realizes and she turns, and they face each other across the living room. And you cry 15 minutes into the movie. Well, that’s how William Wyler came home to his wife. He staged it in exactly that way. So I think we have to make the distinction between movies that are autobiographical and those that are personal. But it is our job as professionals to make all of our films and our relationship with all of our characters personal.

Michael Mann: It’s always personal — and particularly a question for Bradley — directors don’t necessarily see ourselves in the character, but you identify, you project like an actor projects into this character. I’m just curious, because I went to work as a writer a million years ago with Dustin Hoffman when he was going to direct “Straight Time.” And three days in, he fired himself, because he could not possibly act the way he acts and then stop that and move behind the camera and direct. So I see this beautiful last movie Bradley made, which I think is fantastic, and I’m wondering how you do that.

Cooper: First of all, thanks for saying that. I think it’s because I grew up lucky enough to make a living as an actor and because I was always thinking about the process of making films on a set. And we didn’t always have the ability to go to the video village, so I would always imagine seeing what the shadows and knowing what the lens is. And it became sort of second nature, and I just love putting stories together cinematically. My brain just feels soothed by it. Actually, at 40 years old, Clint was kind enough to — really, we kind of made that movie together, “American Sniper,” and even David O. Russell was so collaborative. So by the time I got to “A Star Is Born,” I really felt like I was in the sweet spot artistically. When you think of it sort of objectively, it looks like it’s complicated, but it actually felt the most fluid process for me. I had a lot of time to prep — both of these movies, I spent four to six years on. So everything’s really dialed in.

Payne: But how much do you run back and watch a take of yourself?

Cooper: Mostly I won’t. But if I do, I watch it two times speed, fast-forward with no sound. Just to make sure that it was exactly what I’d set up. But rhythm of a day is so important. And I also would show up, Lenny would be banked, the character would be banked months before we would start shooting. If that wasn’t the case, I’d be terrified. I just show up, and it’s him. And thank God the crew didn’t laugh at me, but he was directing the movie. And it was funny, because depending on what age he was, the rhythm of the day changed. Like, “Oh, young Lenny, this is gonna be a fast one.”

Mann: That’s great. So when Lenny’s cranky, the director’s cranky.

(Laughter)

Justine, you co-wrote “Anatomy of a Fall” with your husband, and the story is about a woman accused of murdering her husband. Did it cause the two of you to examine your own relationship as you wrote?

Justine Triet: Well, he’s alive, first of all.

(Laughter)

Triet: We were, like, blind; we didn’t discuss this. So as a couple, to answer your question, the story and the writing of it, all of a sudden we put ourselves aside, but we could put our fears into the story, our anguishes, our doubts. And to some degree, the process becomes an exorcism where you don’t have to live these things, because you expose them through the story. And so there may be some narcissism involved, of course, but that gets passed up to the point of you can hide behind the fiction. You can live behind the fiction.

So one of the questions that I wanted to explore was the character of a woman who is not a perfect victim. She doesn’t make apologies for herself. She occupies the space that she is in, and so there is a form of power in that. But that was what I was interested in exploring, the woman’s journey in this film. And she’s more judged because of that. She’s more attacked in the courtroom because of this. Because she’s not crying all the time.

Michael, knowing it’s taken you decades to make the “Ferrari” project, what is it that kept you coming back to it?

Michael Mann: The the project started with the late Sydney Pollack and myself and [screenwriter] Troy Kennedy Martin in 1994, and it was just this idea, like you said, about the more specific you get the more universal something becomes. The story of these lives and these romances and the complications these people had resonated with something. It was so specifically Modenese. Not just Italian, not just northern Italian, but this one particular city, and the more specific it became in terms of gestures and attitude, the more and more universal it became. But then I wound up controlling the project, and Sydney and I were together [on it] until he passed away. And then the book had come up for re-option. I said, “This is insane; I tried to put this movie together three times.” No car racing movie has ever made any money, ever. Everybody understood what Ferrari was because it’s an icon for passion globally because of the racing, except the United States. And I would go, “You know, before I abandon this, I better read the script again.” I get to Page 2 and I was completely into it all over again.

Blitz, hearing you talk about “The Color Purple,” you’ve said you almost didn’t want to make it.

Bazawule: Filmmaking is a long, arduous process. We’re sitting here with O.G.s of that process, where you commit so much of your life, your family’s time, your personal time, your health, your mind state. It is something that sucks you in deeply. And so I’m always conscious about what stories I tell. This is only my second film; my first real film, my first film I made in Ghana. This was different, because it was a studio machine, that has completely different machinations. So I had to make sure that I knew why I was doing this. No one from where I’m from has ever made a studio picture. So you step into a place where there’s no one to phone and and say, “I have no idea how to handle tomorrow. Can you help me?” And so I was very clear as to the challenge it was, but I was also clear as to the opportunity it was.

Christopher Nolan has never won an Oscar as a director. That could change this year with ‘Oppenheimer,’ though the competition is fierce. We break down the race.

Alexander, you have cast Laura Dern and Reese Witherspoon very early in their careers, and now with “The Holdovers,” Dominic Sessa as a boarding school student. Is there something specific that you look for in untapped talent?

Payne: Well you mentioned Laura and Reese Witherspoon, throw in Shailene Woodley. Laura not so much, but I got Shailene and Reese when they were still teenagers, but they already had a lot of experience, and they were clearly going places. Dominic Sessa was really picking up a dog from the pound. [Laughs] He had never been in front of a camera before. He was an actual high school senior. And I don’t know, man, I think it’s our job to spot talent. And see an essence, whether the actor is trained or untrained and then see if that actor can be — the word I like to use is “bulletproof” — enough in front of the camera, the unblinking cyclops with the lights and the bearded men with walkie-talkies, and the trucks and all that kind of crap when they get to set. And so if you can go on those safaris, you can come back with some pretty big game.

Celine, I’ve heard you say that you think the job of the director is just to be a professionally passionate person. What does that mean?

Song: When you’re prepping the film, which every single part of it was the first time I’ve ever done it, there are just things that you don’t know. How things are going to get decided on is just based on your belief that that’s the right decision. And some of it is about just being the burning center of everything and being the person who believes in it harder than everybody else. And of course, while you have a lot of doubts, while you’re like, “I don’t know, I’m not sure,” you cannot let anybody else know, because people are looking at you for a certainty that this movie is going to be everything that I’m talking about.

I’m wondering if all of you see directing in that same way. Michael, I know how reductive this is, but how would you describe the job of directing?

Mann: It’s everything. You are the film, the film is you. You’re living every part of it, every component of it, and you’re trying to figure out what strategically, if I break down all the different tasks, what’s critical, what’s not critical. Everything’s expressive, but how is it expressive? So it’s kind of symphonic. To me, prep is everything. If your approach to making films is kind of symphonic, orchestral, you have lots of different instruments and you want to play as many of them as you can. And if you have a perception of how this narrative is going to move through a couple hours of time, all the movements on it, prep is really critical.

Bazawule: A question I have for all of you is how many takes — when do you know you’ve got it?

Cooper: It’s a great question. And I think coming from so many years working as an actor and observing so many different [directing] styles ... I certainly observed when I thought that the director was hurting the film by trying to explore what has already been explored. I think it actually can hurt the actor, the character, because everything you do, you’re still rehearsing, you’re getting to know and you’re relating to each other. And it can start to cannibalize.

Our BuzzMeter film experts are back to predict what Oscar voters will nominate in 10 Academy Awards categories. Vote in the online polls!

Mann: I worked with Al Pacino on two films, and Al always gets there somewhere between takes five and eight. Except when, because of how he works, except when you go into a cover set [changing scenes when weather restricts the day’s planned shoot] and there’s a scene that he hasn’t learned, then that’s a whole different thing. Because he learns the scenes word-perfect two weeks before he shoots them. So he never has a script. He’s dreaming the scene.

Payne: I’m a three-to-six kind of guy. I don’t want to say anything to the actors at the beginning. So takes one and two, I want to see what the actors have been thinking about, how they prepare. I don’t want to mess with anything. And then by about take three, I can jump in and start helping them sculpt a little bit. “What were you doing here? Oh, OK. All right. This part’s great, just faster.” And then, everybody’s on point, by take five or six. Now again, like in this new movie, I did some oners, which are four pages of dialogue. So it’s not just about the actors, it’s about the dolly grip, the focus puller, and you’ve got choreography going on. It can go up to 15 [takes] or something like that. But you’re also getting four pages of dialogue in a shot.

Triet: I’m working with nonprofessional actors in some and also with known actors. It’s really different when you’re working with non-actors. It depends, of course, but I like so much when you mix, because the professionals are taking care of the non-actors, and it creates something very interesting. Sometimes I love to ask directors to [act] because, I don’t know why, but directors sometimes are really good.

Payne: Please cast me someday. No one ever casts me.

Cooper: I always wanted to make a buddy comedy with David O. Russell and Todd Phillips.

More to Read

From the Oscars to the Emmys.

Get the Envelope newsletter for exclusive awards season coverage, behind-the-scenes stories from the Envelope podcast and columnist Glenn Whipp’s must-read analysis.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.