- Share via

Follow us wherever you get your podcasts:

Fresh off the “Better Call Saul” series finale, Rhea Seehorn joins us to delve into the show’s last twists and turns and to give insight into her Emmy-nominated portrayal of ethically flexible attorney Kim Wexler.

If Kim and Bob Odenkirk’s Jimmy McGill character were to get a do-over, how far back in time would they have to travel to put themselves on track for a happily-ever-after? Probably all the way back to the beginning of the series, when they worked together in the mailroom, Seehorn muses. “They would go out with each other, fall in love and then get really, really great therapists.”

In this episode of “The Envelope,” she also discusses her efforts to balance gratitude with confidence in her skills, how her father’s alcoholism shaped her as an actor and the scariest day on the “Better Call Saul” set: when Odenkirk suffered a heart attack right in front of her.

Yvonne Villarreal: Hello, and welcome to another episode of “The Envelope.” It’s actually our final episode of the season, and we’ve got a special one for fans of “Better Call Saul,” or anyone who loves a damn good performance. Because fresh off the heels of the drama’s anticipated series finale, I am speaking with Rhea Seehorn, who plays Kim Wexler, everyone’s favorite ponytailed lawyer who got lured into the con life.

After years of stealing the show with her complex and devastating performance, Rhea recently picked up her first Emmy nomination for the role. And it’s a long-overdue recognition because, as any fan of the show will tell you, the evolution of Kim Wexler has been stunning to watch, and her fate became one of the standout aspects of the series.

Mark, I’m sure you’ve heard about the fandom surrounding Kim Wexler. Tell me you’re not living under a rock.

Mark Olsen: Well, I have to say, this is one of those instances where I personally don’t watch the show, but I’m super aware of the fandom that’s grown around the character and for Rhea. So I can appreciate how overdue this Emmy nomination feels and really just in the nick of time before the series ends.

Villarreal: Look, I know I always try to get you to watch my Bravo shows just because I want to be able to have that connection with you. I really want us to dive deep into that level of TV ridiculousness. But if nothing else, I need you to watch “Better Call Saul,” if only to join me in the sort of Kim fan club, because it’s so worth it.

Let me just say as a woman it was so refreshing to hear Rhea talk about the pride that she had for the performance she delivered as Kim, acknowledging the hard work she put into it and not attributing any of the recognition to being a fluke. I could have spent my whole time with her just talking about that; I told her, actually, that I wish she would do a TED Talk on the topic. But I restrained myself from going too deep into it because we obviously had to talk about the finale.

So let this be a warning to you, Mark, and all our listeners: We’re about to dive deep into that. So if you haven’t watched the finale, pause and come back to us. Otherwise, let’s get to it.

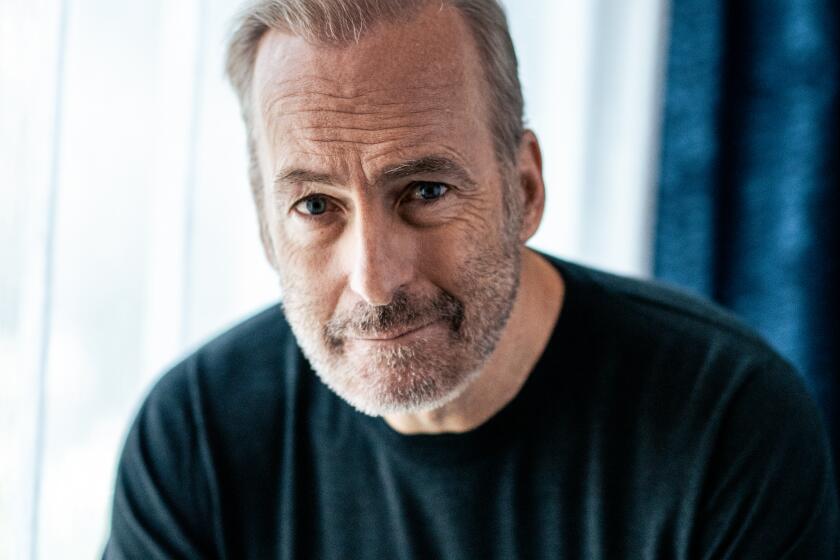

The star joined The Times to discuss Monday’s series finale, why the role left him “ragged,” and his future hopes for the “Breaking Bad” universe.

Villarreal: Rhea, thanks so much for joining me.

Rhea Seehorn: Thanks for having me.

Villarreal: Before we dive really deep into the finale, I want to talk about Kim’s new life in South Florida as seen in the penultimate episode.

Seehorn: Yeah!

Villarreal: After leaving Jimmy, Kim moves there. She becomes a brunette. And we see that she’s working at a sprinkler manufacturer. She didn’t die, as some feared might happen, but she ended up leading a pretty mundane life.

[Clip from “Better Call Saul”: KIM: Did you get the mayonnaise? GLENN: Well, here’s the thing….]

Villarreal: What did you think of that fate for Kim? What did it reveal to you about her?

Seehorn: Well, a part of her has died. She is a shell of a person, in my opinion, and we were very particular in our discussions both with Peter Gould as the showrunner and Vince Gilligan as the director and writer of that episode. We got very specific and very nuanced in our conversations about — there is nothing wrong with her life, quote unquote. This is not some horrible fate that she’s got to live through. It is only because we know what she could have been, and her potential and what she wanted, that it is so tragic to have her not practicing law, to have her not be using her brain to her full potential or her skill set. It’s perfectly fine as far as contentment, but everything is without passion.

Villarreal: It was also such a pivotal episode because we learn what was said in that call that she had with Jimmy.

[Clip from “Better Call Saul”: JIMMY: You have no idea what I did or didn’t do, OK? Why don’t you turn yourself in? Seeing as how you’re the one with the guilty conscience, huh? What is stopping you?]

Villarreal: It was obviously a very jarring call for her because it sort of crystallized how deeply Jimmy has gotten into this life of deception, enough to finally make her feel ready to tell all. She flies back to Albuquerque and signs an affidavit about what really happened to Howard Hamlin. What did you think about that turning point for her?

Seehorn: It is pivotal. And when Vince and I were doing the scenes that lead up to that phone call happening, we talked about: Can you see Kim there? Prior to that birthday song moment and the phone call when you can tell that there is Kim in there somewhere, the Kim that we know. And we said it’s possible that it was performative when she first got there. But this has been years. It’s been all of the “Breaking Bad” years. I think she has become content, not deliriously happy, but content with deciding, “This is all I deserve, and I’m going to make the best of it.” But that’s not going to ever extinguish the fact that she had and has a passion for the law.

I think she still maintains a love for Jimmy. And within that phone call, there is — yes, she’s telling him to turn himself in, and we can only assume she’s caught wind in newspaper articles of not everything he’s done specifically. But he’s on the run from the feds. He was aiding and abetting someone who assassinated people and killed other people by just collateral damage. And I think it is out of love that she’s saying this can’t be much of a life, like, turn yourself in.

When Jimmy says, “Well, what about you?” Kim is smart enough to know that part of that is just defensive, reactive talk. But I found it to be both — yes, he has dared her and challenged her and spurred her on to take on her own conscience, but also I guess the positive side of it, the little hopeful spark, is it’s maybe the first time she thought about, “Maybe I don’t have to live a life of this hairshirt and this penance.” Not that she’ll come back joyously happy, and we see that she doesn’t. But it is a moment for her to think, “Maybe there is a way to alleviate my conscience and be back to living some kind of life that is more truthful.” Because there’s the seed of her that knows that the life she’s living right now is not truthful either. And that’s what I think he sparks.

Villarreal: Well, I want to talk about the finale. Jimmy is caught thanks to Marion, and we’re reminded again of his mastery of the law and manipulation and his desire to protect Kim. I mean, just as he manages to negotiate a good deal for himself, including this amazing stipulation for one pint of chocolate chip ice cream, he winds up throwing that all away when he learns that Kim has confessed to Howard’s death. And at his sentencing hearing, he implicates himself to save Kim, saying that he played a pivotal role in Walter White’s operation and the web of lies and crime that came from that. How did you feel about that sort of turn when you first read the script?

Seehorn: I think that a lot of things about the finale are very purposefully left open for interpretation. I personally think that he was saving himself: the him that Kim always saw, that is possibly a truer self free of what other people tell you you are. Because I also think that Kim, even when she comes completely clean in the penultimate episode, there’s one lie she still tells even though she doesn’t want to be a liar anymore. That is, she says, “if he is in fact still alive” about Saul. She knows he’s alive. She could totally tell the feds to go ahead and tap her phone because he’ll probably call again. She doesn’t. She stops short of making his life worse.

So when ADA Ericsen, played by the wonderful Julie Pearl, calls and says that Jimmy plans on implicating her in things that she did not do that [there] are going to actually be legal ramifications for, I think it hurts Kim and infuriates Kim that he would cross that line. Because I think that her not crossing that line herself was the love that’s still there. So, then what happens in the courtroom, I just think is a journey for Kim going from fury and just absolute shock that he would do this to realizing, “Oh, you just did this to get me here. You’re not going to implicate me in anything.” And then realizing like he’s going to confess not just to crimes but to these very real feelings that he’s had about Chuck and finally sort of letting his profound grief come to the surface. She knows that’s the real him.

I think she’s horribly sad that it’s resulting in an even larger prison sentence than it might have been before. I don’t think she wishes him to be in prison for that long at all. But I don’t think Kim could live with herself if she thought this was a gift for her. I personally don’t think what he’s doing is to save her from being implicated. She has already confessed to exactly what she did. There’s nothing Jimmy can save her from with that. Yeah. But I do think that those last moments in the courtroom are the two of them seeing each other without masks, like they used to.

Villarreal: Well, the closing moments of the finale show Kim visiting Jimmy in prison. What do you think happens when Kim leaves that prison? Do you think she visits? Do you think she visits him often? Does she rebuild her life as a lawyer in Florida or somewhere else? Does the ponytail ever come back? What do you think happens?

Seehorn: Peter said he hopes that people — that the finale actually causes you to continue to hypothesize and think about the next day, the next two weeks, the next six months, the rest of their lives. What that means, and what it means to go in any of those directions. And there was a reason that she didn’t have blond hair when she came back or a pony or even her dark hair in a ponytail. Those things were very specific. I do not think it’s a reset and now everything’s fine and Kim’s just going to become Kim again.

I personally think there’s a rebuilding of sorts and an attempt to relish any kind of second chance at life that is more truthful. And for Kim, I think the more truthful part does involve practicing law and trying again to go about actually helping people. I’m a hopeless romantic, so I can’t help thinking that she’s going to try to figure out how to decrease his sentence while still being on the up and up. You know, like in some way that doesn’t involve a scam. I don’t think it’s the end of their relationship, but I also think there’s plenty of people that will think that she’s never going back there and that is the end of the tale. But that just makes me cry too hard, so I can’t.

Villarreal: A running theme of the finale is this idea of the choices we make, the turning points that sort of alter everything. Jimmy keeps mentioning building a time machine, obviously referencing the H.G. Wells book, and what day he would go back to. Obviously, we don’t get Kim’s perspective on this, but what do you think Kim would say is the turning-point moment that maybe she would go back to?

Seehorn: There’s quite a few. But when I look back on them, I guess maybe the mailroom. It would just be Jimmy and Kim and they would go out with each other, fall in love and then get really, really great therapists.

Villarreal: I would actually watch that show too.

Seehorn: “Jimmy and Kim in the Mailroom Go to Therapy.” That’s the full title.

Villarreal: Was the prison moment the final shot that you did?

Seehorn: Yes. That is the last scene we shot. Well, inside the prison smoking. The walk away from prison was shot on location and had to be done earlier, but the very last thing we shot was us sharing a cigarette in the jail cell.

[Clip from “Better Call Saul”: KIM: You had them down to seven years. JIMMY: Yeah, I did.]

Villarreal: I know this is the longest time you’ve been with a character. How did you say goodbye to her?

Seehorn: I don’t think I have. I don’t know that I will. I think I — Bob said he’s not sure it will hit us that we’re not going back to film more for the next couple of months because we’re used to the show airing and talking about the airing, and then it’s a couple of months while they’re outlining the new scripts and then we’re all putting our stuff in U-Hauls and going back to Albuquerque. The fact that we’re not and that that’s the end of the story, I don’t think that has fully hit me yet.

I love — even if I had the great pleasure of playing the character, I love that that character was on television. I absolutely love the Kim Wexler character, and I will miss getting to perform her scenes. And I will also miss doing the work on the scripts for the way she thinks, which was a very peculiar way of problem solving and suppression and constant subtext that she didn’t let other people know about, which was fun. Blissfully challenging.

Villarreal: You’ve had another big career moment this summer. You were nominated for your first Emmy, and it was actually a double nomination: one for supporting actress in a drama series for your performance as Kim and one for your role in the short-form series “Cooper’s Bar.” And I know you were in London when you got the news. How did it change the vibe of the trip? I’ve never been nominated for an Emmy, but I imagine the glow lasts a while.

Rhea Seehorn: Yeah, the glow is still on. I’m still enjoying this. Plus the show getting nominated and being able to get invited to the prom again. And Bob [Odenkirk] and Tom [Schnauz] and my sound people — it’s great. That day finding out in London, listen, I set myself up to be able to, if I hadn’t got it, be three drinks in pretty quickly. So, we had backup plans. We were already in a bar.

But I’m with my family now at a lake house camp that has lots of rustic cabins, and extended family are everywhere. And the little kids here that are all my little nieces and nephews and cousins, and even my son’s like just introducing me as “Emmy-nominated” when we’re just literally on a dock fishing or at a party where everybody has red Solo cups and I turn bright red, but I am proud. I’m proud of the work I put into this, for sure. But I’m —

Villarreal: Well, and do you feel better equipped to take in, you know, process the success of the show and your Emmy nomination at this stage in your life versus, say, if it happens in your 20s?

Seehorn: It’s hard to break down the word “deserving” of anything, right? Because lots of us have work that was deserving that nobody put a sash on them. But I’m very proud of the work that I did. I took none of it for granted. There’s not a word that I phoned in. I worked very, very hard on the character. And I’ve gotten to a place in my career where I’m not running around any more thinking it’s a giant fluke and I just won the lottery, I somehow got here by no doing of my own. I don’t think that’s that healthy. I spent a lot of years acting like I won a contest, and I think it’s important to find that place — my age and the number of years I’ve been in the business have finally helped me get to a place of figuring out (and I think this is especially true of women) of what’s a positive way to feel proud of yourself and ambitious that is not some of the uglier behavior we’ve seen or uglier behavior that people call out. We’re taught to be more palatable often if you’re women and not brag and not be too full of yourself and this kind of stuff.

I have incredible humility and incredible gratitude for the career I have and the life I have, but that doesn’t need to eclipse feeling like I’m value added when I walk up to a stage. And I think I spent a lot of years thinking, “You get to be one or the other. You get to either think you have any idea what you’re doing or you get to live in gratitude. Not both.” And I was so desperate to not ever appear that I’m not grateful, but at the same time, I’m there to do my job. And if people as smart as Peter Gould and Vince Gilligan or Bob Odenkirk or Tom Schnauz or Gennifer Hutchison, Alison Tatlock, Gordon Smith, I mean, the whole lot of them — if they’re saying, “We did our very best. Please arrive at the sandbox and contribute,” then that’s not a fluke and you owe them to be walking in there with your head up and to have some ideas and to be value added. And I have found that that has only started happening in the last seven to eight years, coinciding with “Saul,” really.

So, that part. I’m thankful for that part when something as beautiful icing on the cake, like getting nominated for an Emmy, comes because I’m like, OK, I know I’m still blushing when somebody is saying “Emmy-nominated Rhea Seehorn,” but it’s also going to be OK to be proud of it. That’s OK.

Villarreal: The listeners can’t see me, but I’ve been nodding my head like a bobblehead. Please give a TED Talk on this topic, Rhea.

Seehorn OK!

Villarreal: A lot of women could use it. But as you’ve said, you’ve put a lot of work into this character and we’ve seen such an evolution with Kim through these seasons. I’m curious, which era of Kim was your favorite to play? Was it the straight arrow at the start of the series or this late-stage Kim, who’s sort of off the rails? Or the one who was in between? What did you find most interesting or satisfying to play?

Seehorn: What’s most satisfying is that I got to play somebody that did evolve. But never these dramatic shifts that felt just for whatever ratings, stunts or to be strange. Even when they were like, “I can’t believe she’s doing that,” it’s like, “Oh, but can’t you?”

When you started to add up pieces and this real thing that happened with Jim where one of the questions became: Did she change, or was she like this and she was suppressing it? It really added to the subtlety of what I got to play. The fact that Peter was not interested — and Vince, when he was co-showrunning for the first couple of seasons — they were not interested in spoon-feeding the audience or telling you it’s A or it’s B, nature versus nurture. Who’s affecting whom? Are any of us innately who we are, or are you only a summary of your experiences in relationships? These are questions that keep me up at night philosophically.

So the satisfaction came from getting to play all of them, because they always felt like very human organic shifts when something would come up when you’re like, “Oh, she’s good at scamming?” It’s like, well, I secretly always thought that she came from some kind of chaos, and I specifically thought she was raised by an addict. We did that a lot on the show where I’m making up backstory and subtext they don’t know about. I would always tell them, “If I ever do behavior that you know is going to ruin something you’re planning, then just come over and swat me and I’ll do something else.” But that never happened. And they were writing things that I was then like, “Oh, that matches.” I mean, when we did the flashback and my mom was an alcoholic, I was like, “Mmmm!” I think I thought it was my dad. But still I had been constructing things around that.

So it was a nice little dance. I’ve enjoyed playing all of them. And all of them have been challenging, which is also — when you tell somebody something was challenging, also what you’re saying is somebody gave me a chance to get better. And I liked it. I like, like going, “That scene, I am not sure if I can pull that one off, but you’re going to have to. You’re going to have to figure it out.”

Villarreal: It became increasingly stressful to watch Kim’s character. The stakes got higher and higher. Were there any particular scenes that stood out where the stress was really felt for you as the performer?

Seehorn: Yeah. I mean, there was quite a few of them. And my breakup scene with Jimmy was extraordinarily difficult.

[Clip from “Better Call Saul”: KIM: You asked if you were bad for me. That’s not it. We are bad for each other. JIMMY: Kim, don’t do this. Kim, please. KIM: Jimmy, I have had the time of my life with you.]

Seehorn: And my scene where we almost break up. But instead, she says, “Or maybe we get married.” Very technically challenging scene.

[Clip from “Better Call Saul”: KIM: I cannot keep living like this. JIMMY: Oh, no, no, Kim, we can fix this. KIM: Shut up, Jimmy. Jimmy, you know this has to change. If you don’t see it I don’t know what to say because we are at a breaking point. Either we end this now, either we end this now and enjoy the time we had and go our separate ways, or, or…. JIMMY: Or what? KIM: Or, or … maybe … maybe we get married.]

Seehorn: Kim became increasingly impulsive and it bit her in the ass, but at that time in the show, she was rarely impulsive. Everything needed to be methodically thought out, and if anything, that was her response to Jimmy’s impulsiveness. Because, you know, she started in this place when they’re sitting on the bed eating pie, saying, like, “Ugh, you fabricated evidence. I love you and I’m in this enough that I’m not going to walk away. And I’m also attracted to that rebellion, so I’m not walking away. But here’s the solution: Just don’t tell me about anything you do.” Cut to the marriage and what happens after that. She was like, “Here’s the only way I can control it, oh, I know: Tell me everything. Tell me every single thing because I will be the person that can make sure no bombs go off.”

And this was also the increasing level of her ego, which I found that, you know, people were seeing that as heroic. The “I save me, you don’t save me” became a character flaw, in my opinion. She refused to accept help. And you go all the way on the end of that spectrum to, “Oh, Lalo’s alive, and he might be coming for us. I’m just not going to tell Jimmy.” My fiancé and I call that, and it’s a therapy term, “managing people.” You think you can manage — she’s like, “I don’t want him to have PTSD, so I won’t tell him.” OK, well, he might show up and blow your heads off. That’s the only downside of that. But she thinks she thinks he’s got it all under control; clearly does not.

But I was totally unaware of what [Episodes] 612 and 613 had in them. But I know I finished that scene thinking, “I don’t think she thinks she deserves anything that has any illumination to it anymore. It just has to be gray. That’s all she deserves, and she shouldn’t come anywhere near decision-making or being the person that’s in charge of something.” And it’s just tragic. I had said for years, “Yeah, she might die. I don’t know the ending of the show.” But I also said there are things more tragic.

I mean, there aren’t truly. But we’re talking, you know. Plot line. Figuratively. I guess what I would say is it’s not the only tragedy. Dying is not the only tragedy for a character like Kim, because now we’ve seen what she could be. We’ve seen what she could have been. And it’s awful.

And I do think that they have a real love story. I have always thought that their love for each other is sincere, however convoluted at times, and even though they clearly get off on scamming and stuff together, I cherished all the smaller scenes where they’re just eating Chinese food together or brushing their teeth. So, those things to me are the weave of the fabric that makes the explosive things matter. It’s why people give a crap when we break up. It’s because he always holds my briefcase while I’m going out the door. It’s because we brush our teeth and make jokes. And all the way through it, our characters support each other.

[Clip from “Better Call Saul”: JIMMY: It’s an old gag, but sneak into his country club, and put Nair into his shampoo bottle. Then he takes a shower and … KIM: His hair falls out. JIMMY: Yeah. KIM: Nice! Or we pour a barrel of chlorine into his swimming pool so that ... JIMMY: ... bleaches his hair, and eyebrows. KIM: Yes, and the eyebrows.]

Even when Kim wanted him to not do bad things, there was always this constant reminder of “You said you wanted XYZ. You said you wanted a seat at the big kids table. You said you wanted to be seen, why can’t you be seen as just as deserving as the HHM people and this, that and the other? So if you sell burner phones in a parking lot, that is not going to help you with the goal you said you have.” Which is very different than, “What’s wrong with you? You’re a piece of crap,” which other people do to him. “You’ll never be anything.” And hers is more like, “Hey, man, I’ll help you get wherever you want to go.”

Villarreal: Something that I found interesting during “Breaking Bad’s” run was many predominantly male fans came to see Skyler White as a villain standing in Walter White’s way and subjected the character — and the actress, Anna Gunn — to a lot of vitriol as a result. What was your reaction to that sort of discourse, whether as a viewer or as you prepared to take on the role in “Better Call Saul”? Were you worried that as the woman who was sort of like the moral center initially, that you were going to come under fire in that way?

Seehorn: Well, all of that is a lot to unpack. I have to say, first and foremost, what she got thrown at her is so far beyond undeserved and unfounded and has no ground. If you actually look at the storyline and the authentic choices she made for her character, it’s ludicrous and horrible. And no one should be attacking an actress for a character they’re playing, even if you feel that way about the character. It’s so stupid. And I hate that she had to go through that.

People do often love to hate the obstacle in the way of your protagonist, and that happens. She wrote that lovely New York Times article that I think speaks to all of this far better than I can about why it became so personalized, and being a woman, and the connection of those two. So, my concerns really rested in the fact that, unfortunately, if social media decides to hate you and they go on a rampage, there’s very little you can do about it. I knew I wasn’t a character from “Breaking Bad.” I knew that some people are just going to want this show to be “Breaking Bad.” Some people are only going to want cartel stuff. Some people are going to want Jimmy to hurry up and become Saul Goodman and why is this dinky, blond ponytail in our way? I’m sure those people exist.

I think television audiences have evolved a little bit, and part of it is because if you build it, they will come. There are so many more enriched, complex female characters that are allowed to disagree with their partner and still be fascinating, interesting, and you want to follow them. And I think there are tons of men out there that want to see characters, female characters, be just as interesting as the male characters. I think probably the majority of them. So I do think we’ve helped our audiences see the brilliance of performances like Anna Gunn’s. And so I step into a world that’s already built a little better for it. But yeah, I knew, if they decide, like, “Why is she in the way? Get her out of here,” I’m kind of screwed.

Villarreal: I’m going to take a little bit of a turn here. I have to say, so many people, myself included, were really bereft when Bob had the heart attack while filming. I imagine it was a scary thing to experience. It happened while you guys were shooting a scene together, or rehearsing. Do I have that right?

Seehorn: Shooting, yeah.

Villarreal: How is it to come back to set after that?

Seehorn: Well, the alternative of never coming back to set without him is not something I can even allow myself to fathom. But I got forced to fathom it for a couple of hours, and I don’t ever want to again. He was with Patrick and I, shooting, and they were turning the cameras around. I think we’d been shooting for 10 or 11 hours, and it was a big turnaround instead of a small, which for anybody listening that doesn’t know, that’s just like, “We’re going to move cameras and lights and everything significantly to another area in the room or person.” So it’s a large change instead of a small change. When you have those, people often go back to their trailers instead of hanging out on set because it’s going to be a while.

Thank God, Bob likes Patrick and I enough, he chose to hang out with us. So they were just hanging together. And he was watching the Cubs game, and we thought he was fainting, but we quickly realized something very dire was happening and then screamed for help. It was very hard for people to hear us because these airplane-hangar-sized stages, there’s work going on, there’s machinery, and then there’s massive echoes. I was told later that some people thought we were laughing-yelling at first because it’s very hard, and we kind of figured that out. So we started to yell, Patrick and I started to yell, “Emergency, 911, it’s Bob,” so that people could try to make out words. And then they came.

We had the great fortune of Angie Meyer, our new first A.D., had been an EMT responder in Texas for years. Rosa Estrada, our head COVID officer, who has been our set medic prior, has been like a wartime medic in the field, fast responses, emergency responses. Another set, a medic person who, it was his first day, knew CPR. So he got oxygen sent to his brain almost immediately the second he flatlined — or as he said it, “like, died for a second.” So there was no brain damage. He also was in the best shape of his life. People are like, “I thought he was healthy.” He was. And that’s how he survived this well, with no physical damage and with no brain damage, because he had been training for his action film, for “Nobody,” for three years. Best shape of his life.

It’s also just crazy that one of the worst days of your life becomes one of the most miraculously best days of your life in a 24-hour period. He was in ICU, and, you know, you’re not really supposed to see anybody because we don’t even know how he’s going to recover or whatever. And his amazing wife and children knew what Patrick and I saw, so they wanted us to see him alive and laughing immediately. And they allowed that. And I was forever grateful for that.

Villarreal: That’s powerful, especially because, you know, this seems to be the longest job you’ve had, working on “Better Call Saul.” Actors can only be so lucky to get multiple seasons like this, and you really formed a family. Something I didn’t know about you is like your father and your mother had careers in the Navy, which required the family to move around a little bit. How did that sort of impermanence growing up shape how you navigated the world at a young age, and how do you think it helped you in a career in acting?

Seehorn: I’m sure it affects kids that move around. My mom worked on bases, but it was my dad being NIS is why you’d have to be stationed somewhere. And then that impermanence, location-wise, slowed down in, I think, fourth grade. So it wasn’t throughout grade school, but definitely my youngest years. But you learned to adapt. Yeah. I think “bloom where you’re planted” became a skill set. You gotta figure it out. It was like, sure, I missed people when they moved, but you have to figure it out.

Probably even more influential to me was being a latchkey kid and being a kid that really, really, really liked telling stories and having stories told to them, which eventually became an obsession that I was grounded for quite often with watching TV and sneaking TV and movies, and just, from a really young age, just really obsessed with the power of “Why can some people make you forget everything that’s bothering you and take you on a journey from A to B?” Anyway, yeah. I had my own reasons for wanting to escape, and I really, really liked stories.

Six Emmy contenders, including Adam Scott, Jin Ha, Rhea Seehorn and Kaitlyn Dever, discuss learning from teachers, collaborating with directors and watching themselves in our 2022 Envelope Drama Roundtable.

Villarreal: Well, I want to go deeper on that, if you don’t mind. In reading about your background, I found myself connecting to a part of your story — and I hope you’re OK with me going here — but my dad was also a high-functioning alcoholic until he very much wasn’t. And he too died from complications from the disease a few years ago. And I —

Seehorn: Oh, I’m so sorry

Villarreal: Thank you. But I had wondered how that shaped the path you took, because I found myself leaning into wanting to write about TV because it was my connection to him that had the good memories, like watching reruns of “Mary Tyler Moore” or “The Bob Newhart Show” and laughing. I know you had been on a trajectory of pursuing the fine arts in school, and your dad liked dabbling in painting as a hobby, if I read that, right? And so I know you still paint, but you ultimately became an actress. What do you think acting offered you in the time following your dad’s death?

Seehorn: You know, it’s easy for the timeline to look like: He died and then I just felt free enough to go become an actor. But there were definitely things going on there that are complex. And while painting is not a lucrative backup career …

Villarreal: Oh, yes.

Seehorn: … I had plans to go into exhibition design and I wanted to be a curator and I was hoping to get an internship at the Corcoran or the Smithsonian or National Gallery, blah blah blah. And when I look back on it, I know I wanted to be in entertainment, but I was chubby at the time, and I didn’t know anybody in entertainment, and I didn’t understand that acting was a craft. There’s tons of brilliant chubby actors. I’m just saying at the time when you’re watching 1980s American television, it doesn’t look like there’s a big open lane for people that don’t look a certain way. Then I started watching theater and I was like, “Oh! They seem to have some parts for me.”

It was a confluence of a lot of events. My dad did paint. My sister paints and draws. We definitely shared that with my dad. It seemed to be the way he could process emotions until the alcohol became the bigger crutch, unfortunately. And even all the way back to — he was in the Vietnam War and he has sketches, charcoal sketches, from that time that clearly are a person trying to sort out, you know, back when men of a certain generation were not at all saying they needed therapy or anyone helping them get it. So I have a lot of sympathy for that.

I also didn’t have then but do now — and in my early years of acting developed — a lot of sympathy and empathy for what my mom went through, being the wife of an alcoholic and trying to hide things from people. I have sympathy and empathy for what my sister went through when my parents got divorced and we had to decide where to live. And I couldn’t stand the thought of breaking either of their hearts, so I made her choose so that I could say, “I just want to do what my sister’s doing.” And I’ve spent so many late nights apologizing to her for that. What I’m saying about this experience is that it fed into and magnified the fact that it’s not binary. It’s not “addicts are monsters are horrible parents.” Some of them are pretty good parents, often great, doing the best they can, making some really poor decisions on occasion, but so are a lot of non-addict parents.

And the whys of why people behave how they behave, pre-me understanding why my dad’s behavior changes at certain hours of the day and post-my understanding. And even the latter, latter years where you are asking them to quit, begging them to quit.

Villarreal: Yeah.

Seehorn: And understanding my mom’s decisions and the decision to divorce somebody, especially if the person, if the alcoholic, is acting like a victim and you want to rally around them. And the decisions his family made …

Villarreal: Oh, yeah. You’re speaking my language, Rhea.

Seehorn: Decisions people make when a funeral happens. The decisions people make when they don’t like the real reason this person died, so some of us are going to pretend he died of something else. Insanity. And I’m 18 and I’m like, “What are we doing?”

Villarreal: I’m not an actor, but I would imagine acting came somewhat naturally for you because I feel like as children of alcoholics, we’re like the best actors because we’re always having to pretend everything is OK.

Seehorn: Hell yes.

Villarreal: Would you agree with that?

Seehorn: One hundred percent, Yvonne. But additionally, tell me if you had this. Additionally, you develop a really great skill set for observing behavior and trying to figure out the why behind it. And that’s a third of script analysis right there: What was the objective with this line? What was the tactic you used at that time, and did you get it? You didn’t get the objective, so that’s why you then said this. Otherwise it would have said, “exit stage left.” So your objective has not been met or you shifted tactics or something.

I was just fascinated by behavior and what probably was a coping mechanism for you and I when we were younger, to observe rather than be in it. But also, like you said, believe me, I am somebody that needs to make sure everyone’s OK in the room because something might blow up at any moment.

Villarreal: Yes. Yes.

Seehorn: And if you spent any time in Al-Anon, which I have, you know these wonderful survival skills when we were growing up have become obstacles as an adult. Because not everyone in the room wants me to fix them, thank you very much. Yeah, there’s a lot of it, but I don’t want that to sound like acting came from an unhealthy place. Instead, I celebrate that that kind of — and look what you’re doing with it. It isn’t about prostituting our pain of, you know, “Great. I’m going to go out there and purge all my emotions because I’m so damaged.” I don’t feel that way at all. I don’t feel that way at all.

I feel like, “Man, I wish he could have beaten the disease, because he’s such a great person and I wish he was around.” But I think that being an observant kid and watching life and watching the decisions my mom had to make, my sister had to make, I had to make, people around us make — watching that interior versus exterior of what people think about. What’s privately going on in your house versus what’s going on outside versus how we’re going to behave when we get to school. Being popular one year and then being bullied another year and then back to popular. And it was like, “Was it my pants?” Everything about growing up to me felt safer if I was allowed to think about the whys of human behavior. And I think I probably would have gone into psychiatry if I didn’t find acting.

Villarreal: Oh, I tried. I tried.

Seehorn: Did you?

Villarreal: Yes.

Seehorn: I’m definitely an armchair psychologist.

Villarreal: I loved a good psych class in college.

Seehorn: Oh man, right? Oh my God. We leave parties all the time, and my husband, my poor fiancé, he’s fascinated by behavior. But the level to which I am — like, I need to talk about the dude that was on the bench by the front door for, like, seriously two hours. And yeah, and the woman that kept asking me to taste the almond milk to tell her if there was sugar in it, when she could taste it herself, I’m like, “Why would somebody do, like, why wouldn’t you just taste it?” He was like, “I don’t know!” But I’m always like, “Oh, I’m going to put this in a scene. I’m going to put this in a scene somewhere.” Which, again, people, it’s not a crutch. It’s a fascinating way to go through life, and you get to make a living at it. Come on. It doesn’t get better. Plus, I’m part of storytelling. It’s the best.

Villarreal: Yeah. And I would imagine after you wrap a long, successful series like “Better Call Saul,” that it could either be scary or exciting, you know, scary to end something that has been such a stable part of your life for the past few years or exciting to be starting something new and fresh again. How are you feeling right now?

Seehorn: I don’t think it felt real until the finale came out. I’m in some deep denial. Also a skill set children of addicts learn. But yeah, I’m scared. I’m sad. Leaving that kind of writing, ugh! But I also realize, another chapter will unfold. But the writing in “Better Call Saul,” the style of portraiture and character storytelling that they do and do so well and that kind of work with this crew, this set of writers and directors, this set of scene partners — I mean, it doesn’t get better than Bob. I adore him and we adore each other’s work ethic and we adore the characters each other made. So we get to put all of that together when we act and truly just trust. I’m going to miss all of that.

Villarreal: Any parting words for Kim?

Seehorn: Well, listen, there’s going to be open interpretation about this finale, and I think all are valid. But suffice it to say, in real life, I am a hopeless romantic. So my parting words for Kim are: Please, please, please, please, please follow your heart, because I want you to.

Villarreal: Well, Rhea, it was such a pleasure speaking with you. Thank you for giving us your time. And congratulations on a great run on a great series.

Seehorn: Thank you. It’s been a pleasure.