Which ‘Macbeth’ is for you? Depends. How sparse or how bloody do you want it?

- Share via

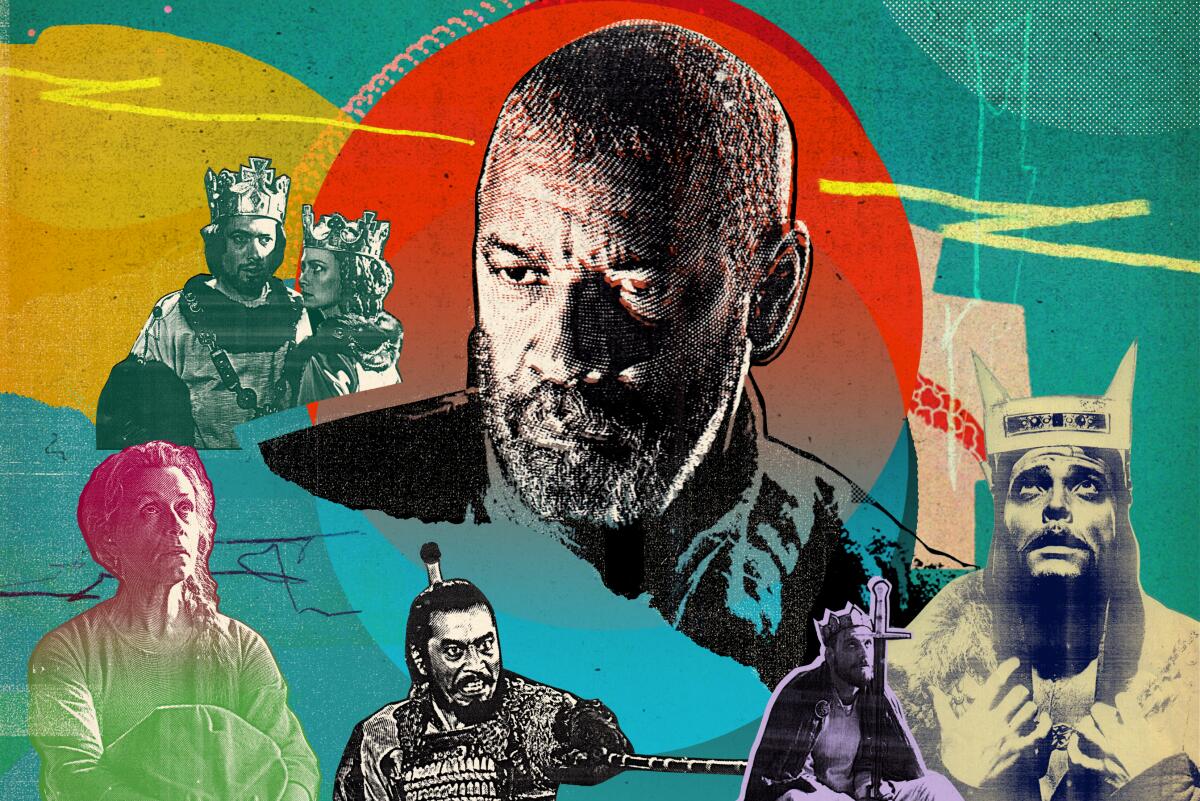

Joel Coen’s film adaptation of “The Tragedy of Macbeth,” starring Denzel Washington and Frances McDormand, arrives a mere six years after Justin Kurzel directed Michael Fassbender and Marion Cotillard in his own adaptation. How much “Macbeth,” one might reasonably ask, does a viewer need? After all, we haven’t seen a major big-screen “Hamlet” in years.

When the battle’s lost and won, however, we must acknowledge that no two “Macbeths“ are anywhere near alike. Some are sparse, some Baroque. Some are bloody, others restrained. Sometimes the blood-stained king is haughty; other times, he’s terrified of his own murderous deeds. The play is well suited to interpretation. That’s why Macbeth and his nefarious wife get to keep visiting the multiplex, or at least the art house.

Let’s start with the latest film. This “Macbeth” is boldly abstract, even dry in an oddly appealing way. The heavy shadows and jutting angles suggest a German Expressionist horror movie, perhaps “Nosferatu” or “The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari.” Flocks of birds portend evil. The nightmare is largely in the heads of the doomed protagonists, and on their faces. The film’s Oscar nominations for cinematography and production design are well earned.

Those faces say so much. Washington’s reveals naked ambition, deep regret and childlike curiosity: Is this really happening to me? Much of Washington’s performance lies in the space between words. McDormand’s is impatient, embodying one of the play’s most famous complaints of her hesitant husband: “What beast was’t, then, That made you break this enterprise to me?” Put another way: Just kill the king already, so you may take his crown.

Aesthetically, Coen’s Macbeth most resembles Orson Welles’ 1948 version (which is, unfortunately, very difficult to stream). This was still a fertile artistic period for Welles. In 1947, he made the classic noir “The Lady From Shanghai,” and in 1949, he gave perhaps his best performance, in Carol Reed’s “The Third Man.” His “Macbeth” is a sea of Dutch angles and abstract imagery. It is minimalist, partly because Welles was scrambling for money to pay for it. It can’t match the imagination of his groundbreaking “Voodoo Macbeth,” directed by Welles for the Federal Theatre Project in 1936. But, like Coen’s film, it has a sparse majesty all its own.

If sparse isn’t your thing, you might be a fan of Roman Polanski’s adaptation from 1971. The frame is crowded, full of loud and bloody doings. Jon Finch, in the title role, pouts petulantly; his Lady Macbeth, played by Francesca Annis, oozes sensuality. (Hugh Hefner was the film’s executive producer.) Where the witches in Coen’s film are so economical they’re all played by the same actress (Kathryn Hunter), Polanski gives us a massive coven of naked hags, mixing a truly vile-looking elixir.

This was the first movie Polanski made after his wife, Sharon Tate, was killed by the Manson “family,” and it is drenched in blood. When it’s time for Macbeth’s foe to lay on, Macduff runs Macbeth through with his sword, then chops off his head, which goes bouncing down a flight of stairs before having its crown removed. Polanski’s “Macbeth” can be summed up by the title of a film from later in his career: carnage.

By contrast, the Fassbender/Kurzel “Macbeth” has an ethereal feel, almost like a Terrence Malick film. Dust motes float through the air. Hushed, delicate voiceovers accompany slow-motion action sequences. Fassbender’s Macbeth comes across as deeply contemplative, even meditative, and Cotillard’s Lady Macbeth follows suit. This is a handsomely mounted but oddly mellow “Macbeth” that seeks to emphasize every near-whispered word.

The best film adaptation of “Macbeth” actually isn’t even “Macbeth” — except it is. Just as Akira Kurosawa turned “King Lear” into the grand epic “Ran,” he chiseled the uncanny “Throne of Blood” out of “Macbeth.”

The time is the 16th century. The great Toshiro Mifune plays Macbeth surrogate Taketoki Washizu as truly bewildered by the curse and burden of the prophecy, here delivered by an old woman at a sewing wheel, symbolizing the cycle of life, death and rebirth. His wife, Lady Asaji Washizu (Isuzu Yamada), plays her part in the tragedy as a quietly self-assured gangster, pushing her husband toward crime at every step.

The film is performed in the style of Noh Theater, with slow movement and poetic language. The hem of Lady Washizu’s robe lightly, portentously, squeaks across the floor whenever she walks. But the real showstopper is the climax, when Washizu is trapped by a barrage of arrows, limiting his movement until there’s nowhere to go and death inevitably comes.

The common denominator through all these productions, appropriately enough, is ambition. That’s the subject of the play; it’s also what it takes to make “Macbeth” sing in a different register than what we’ve heard before. So lay on, “Macbeth.” We’ll likely be seeing you again soon.

More to Read

From the Oscars to the Emmys.

Get the Envelope newsletter for exclusive awards season coverage, behind-the-scenes stories from the Envelope podcast and columnist Glenn Whipp’s must-read analysis.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.