Fathers and daughters have a special bond, captured this season in several films

- Share via

Stories about the joys, missteps and challenges of parent-child relationships have long been a mainstay in films with their inherent complexities proving fertile, relatable territory for comedy, drama and even horror.

This awards season has seen a host of prize-worthy films about the parent-child experience, with a handful of very different pictures focusing more tightly on the dynamic between fathers and daughters. But what exactly is it about this particular pairing that can make for such deep and dimensional storytelling?

“It’s an incredibly formative relationship, so wherever you end up as an adult daughter has a lot to do with your relationship with your father,” actress Rashida Jones said by phone from her Los Angeles home. She stars in Sofia Coppola’s comedy “On the Rocks” as Laura, a sensible writer swept into a detective-like caper by her exuberant, bon vivant art dealer dad, played by Bill Murray.

As the daughter of music legend Quincy Jones, she is no stranger to navigating life with a larger-than-life parent. “If you have a big, charismatic father who changes the climate of the room when he walks in, it does change the way you move in the world,” Jones said. “I think [Laura] is probably defined by her love for her dad, and I think this movie is a bit of a breaking away from that to become her own person, which I think is also extremely important as an adult daughter.”

Jones added, “But I do think that there’s this long history of women belonging to families and belonging to fathers and belonging to men that makes it harder for women to really break away from that.”

That concept also infuses the powerful, mind-bending drama “The Father,” adapted by director Florian Zeller and Christopher Hampton from Zeller’s acclaimed play. In the film, Anthony Hopkins portrays (the also-named) Anthony, a formidable patriarch battling both dementia and the will of his devoted, if beleaguered, daughter, Anne (Olivia Colman).

“Not to make a sweeping generalization, but I think it’s much harder for daughters [than sons] to break away and get out and be objective about their parents,” Hampton said during a recent call from London. “I think they suffer the sort of competing claims of husbands, children and parents much more vividly than maybe men do.”

Hampton, who has two daughters, believes filial duty both drives and haunts Colman’s vulnerable Anne. “I think one of the subjects of this film is the sort of anguish of the daughter who loves her father [and is] trying to do everything she possibly can to ease his final years,” he said. “The sort of obstacle course that he puts her through, not necessarily purposely but because of his illness, seemed to be the sort of emotional heart of the story: the division of her loyalties between her personal life and her feelings for her father.”

Zeller, speaking by phone from his home in Paris, explained his approach to Anne’s conundrum: “I wanted to explore this moment when you become in a way the parent of your own parent. Even though you are the daughter, in the story it’s as if she was starting to be almost the mother of her own father. It’s the inversion of the relationship.”

And what might be a source of Anthony’s push-pull with Anne? “For a father, you can see all the women [in your life] in your own daughter,” said Zeller. “It’s like everything is summed up in one human being. I think it’s a really complicated projection and relationship.”

In “The Glorias,” the panoramic retelling of the life of writer, feminist and political activist Gloria Steinem, director Julie Taymor (she cowrote with Sarah Ruhl) spends brief but pivotal time depicting the impact that Steinem’s nomadic, Harold Hill-like entrepreneur dad, Leo, had on the woman she would become.

“He is the first romantic character in her life,” said Taymor, phoning from her home on Martha’s Vineyard. “In this case, as in many, the mother ends up having to say, ‘Do the right thing,’ [but] the father gets to be the one you have fun with … who takes you out. He’s not necessarily the disciplinarian: He maybe [would be] more for a son than for a daughter.”

Drilling down on what she called Gloria and Leo’s “‘Paper Moon’ relationship,” Taymor added, “This father in particular really supported her critical thinking. He was right there letting her be the ‘man’ that he is. You see her father treat her as an equal.”

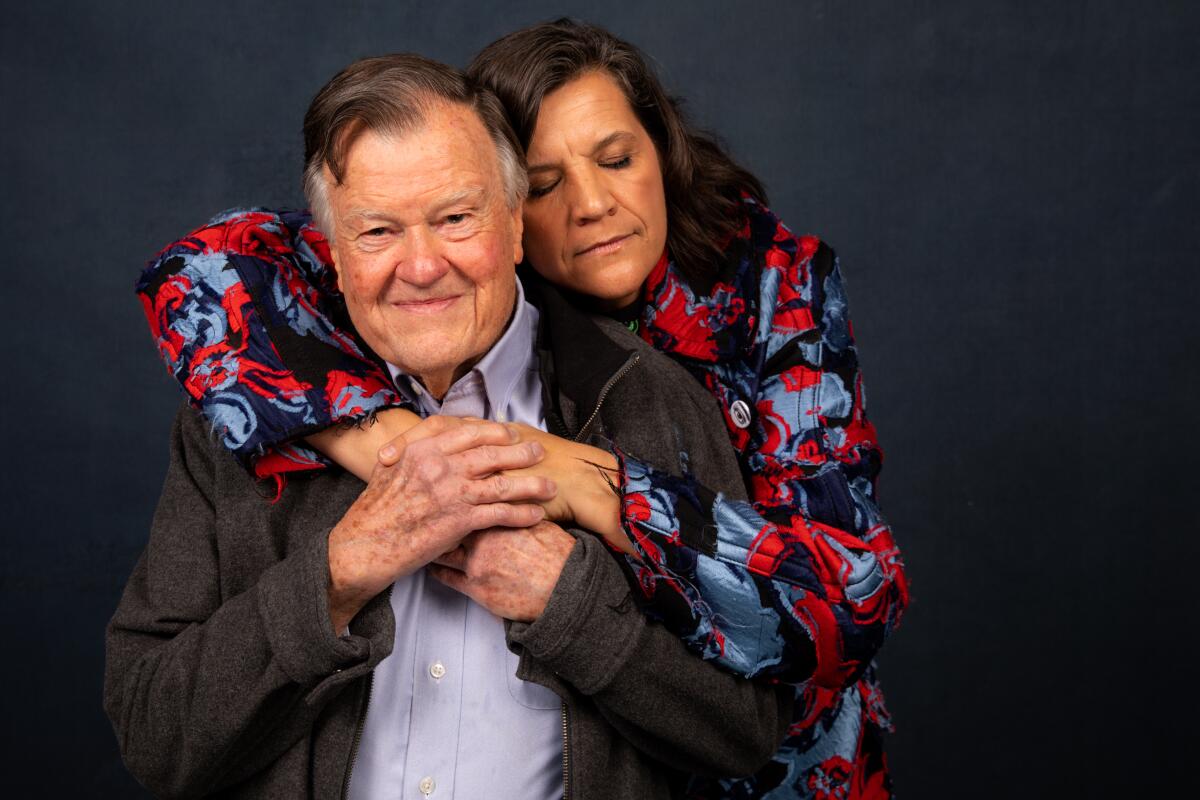

Another real-life father-daughter bond gets tender, often whimsical treatment in Kirsten Johnson’s documentary “Dick Johnson is Dead.” In a recent call from her Connecticut home, the filmmaker described her work as “an experiment to try to trick time and defy death and keep him [her ailing dad, Dick, a former psychiatrist] alive forever … but also keep putting him back together when dementia’s trying to pull him apart.”

The deep and abiding love between the Johnsons fuels this bittersweet film and highlights perhaps the most “functional” father-daughter duo on screen this season. Still, Johnson remains a realist. “Parents and children expect impossible things from each other,” she said. “If we were to talk frankly about this, we can say there are some fathers who are incapable of respecting the boundaries that happen when their daughters become sexual people.

“In my case,” Johnson continued, “I feel like my father always respected my boundaries as a human. There was trust and respect, and I think that the challenge for many men is to kind of move through that frontier from when their daughter is a child to their daughter becoming a young woman.”

More to Read

From the Oscars to the Emmys.

Get the Envelope newsletter for exclusive awards season coverage, behind-the-scenes stories from the Envelope podcast and columnist Glenn Whipp’s must-read analysis.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.