- Share via

The video in question could have been recorded in south Texas, or in any Chicano peluquería with a mural of La Virgencita emblazoned on the wall.

The barber wears a black dress shirt with every last button fastened, tucked into a pair of high-waisted dress pants; a wide-brimmed hat on his head is adorned with a long, flamboyant feather. Oh, and the client in the chair? Olvídalo! His face is tatted up and, after his coif, he sports a hairnet reminiscent of Lou Diamond Phillips (Filipino, by the way) in “Stand and Deliver.” The whole thing made me feel nostalgic and confused, because this video wasn’t recorded in Texas or even in the United States. The caption helpfully offers: “Pachuco style is becoming popular in Vietnam.”

Get the Latinx Files newsletter

Stories that capture the multitudes within the American Latinx community.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

This initiated what is often charitably referred to as “discourse” online, much of it including a term that’s come to sound like nails on a chalkboard: “cultural appropriation.”

Much of what gets said on social media is discardable, but this video and the response to it, including those unhappy with Vietnamese people dressed in pachuco style, nonetheless tickled my brain and made me think about how culture works, how it spreads and who gets to engage in it. Which is to say, it made me think of Yugoslavia.

But before we get to that, let us ask, what’s a pachuco? The term can easily be traced back to El Paso (shoutout to my abuelita, who lived there), also known as El Chuco. There’s a “chicken or the egg” situation at play here, as some claim the name Chuco comes from the pachucos themselves. The city became so associated with them that it stuck. If that’s the case, where did the term “pachuco” come from?

My favorite theory is that it comes from a then prominently displayed sign outside El Paso for a shoe store called Shoe Co. The story goes that whenever Mexicans crossing would be asked by immigration officials where they were going, they would either say “pa’ El Chuco” or “pa’ el Shoe Co.,” depending on who you believe.

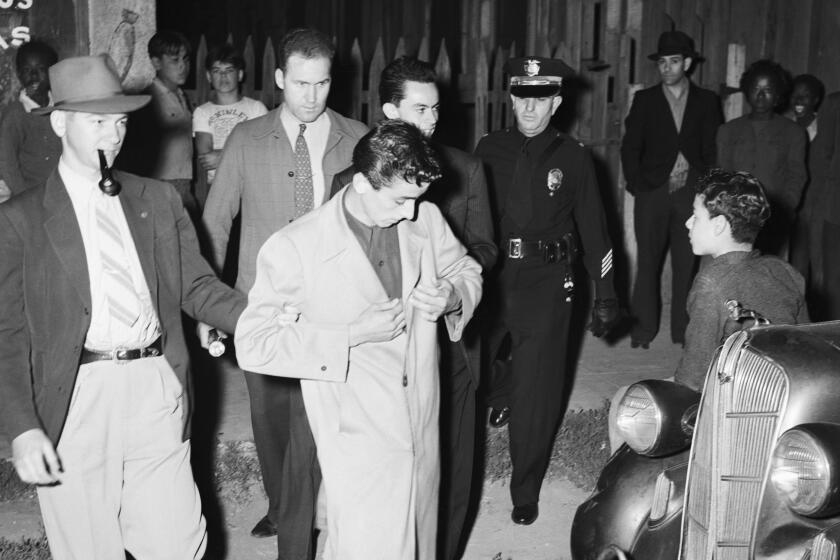

The Zoot Suit Riots were a series of racist attacks on the Mexican, Black and Filipino communities of Los Angeles during the first week of June 1943.

The signature pachuco style is associated with the zoot suit, an assertive, dandyish getup that includes wide-legged, high-waisted pants, two-tone spectator shoes, a plumed fedora and, most importantly, an excess of fabric. It borrows from Black styles, which also sprung up near the barrio, and it achieved iconic status in American fashion after the Zoot Suit riots in 1943, which saw U.S. servicemen clashing with “unpatriotic” Latinos, Filipinos and Black people in Los Angeles in a violent overflow of racial tensions.

So, yes, the zoot suit and the pachuco style have roots in substantive racial histories. That doesn’t change the fact that pachucos are perhaps the worst group to white knight for on the grounds of cultural appropriation. Knowing pachucos myself, they want everyone else to be a pachuco, because being a pachuco is sexy and chido.

I think back to this “Only in El Paso” video that explains it well. It interviews pachucos who talk about their culture of unity. Chicano culture was born out of arbitrary borders, its inheritors having to dance around geopolitics, multiculturalism, multilingualism and sentiments of non-belonging. Borders are, obviously, something of an enemy.

“A pachuco does not believe in cultural boundaries,” says one pachuco from Ciudad Juárez. “Borders don’t matter. Nothing matters except being unified.”

“You wanna be a pachuco?” says another. “Go ahead and do it!”

The rise of social media has profoundly impacted cultural identity. Optimistically, it has served as an equalizer of sorts, allowing historically marginalized voices a platform to be heard. But it has also cultivated an ecosystem where there’s incentive to gate-keep, where identity is its own form of capital. In an influencer age crowded with voices, it’s shrewd to find a lane and to thin the herd in terms of who gets to talk about certain topics.

Over the last decade or so, ethnic identity, at least among the internet literati, has been governed by a certain essentialism that holds that culture is biologically ordained by blood. It is a solemn, sacred, fragile affair that must be protected with utmost care by those qualified to handle it, by individuals appointed to this role by virtue of their birth. That’s the least charitable reading of it, but, hey. The internet is not known for its charity.

The concept of cultural appropriation has been a handy tool to such ends, serving as a broad category of crime that covers everything from genuine grievances, such as the pilfering of Black American musical trends by an industry that consistently neglects and disrespects them and truly absurd claims about who is “allowed” to “make sushi.”

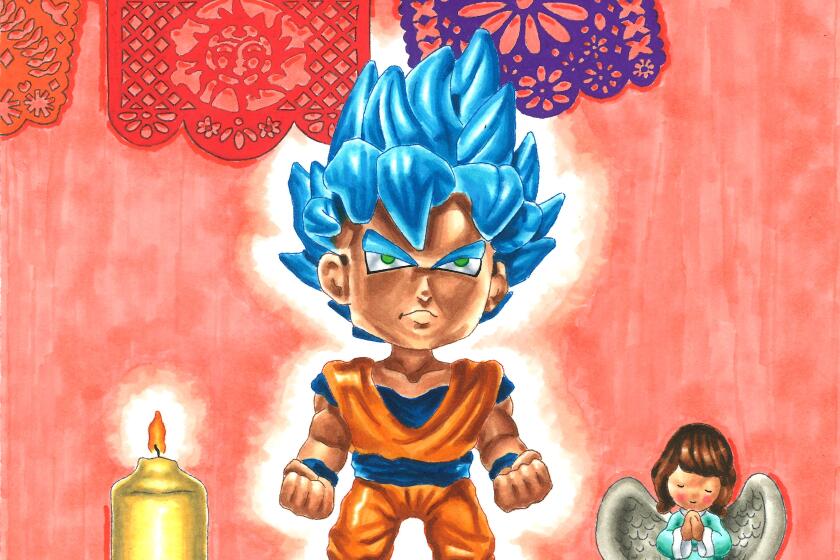

Legendary manga artist Akira Toriyama died Friday. Among his work was the ‘Dragon Ball’ series, which has found mass success with Latino and Latin American audiences.

I’ve burned out on cultural appropriation because it seems to be overly obsessed with cultural trappings and aesthetics and less so with the material realities that give rise to inequality. I generally dislike its relationship to concepts of authority and ownership, but I can see how it’s an ideal framework for a set of commentators who are primarily operating in images that crop up on their social media feeds.

My favorite quote-tweet of the Vietnamese pachuco video says “Latino belt theory vindicated again.” This itself is a meme asserting that there is a “Worldwide Latina Belt” stretching from Mexico to South America to Southern Europe to Northern Africa and on to Southern Asia. People from these areas have a certain little something in common, an X factor that’s hard to define, but is recognizable in specific facets of their culture. As one person astutely put it, “If the CIA has picked your ‘president,’ you’re Latina.”

As silly as it is, it’s a better reflection of the absurdist nature of geopolitics and identity than most people on social media put forth. It holds “anyone can be a Latina, sort of,” and humorously positions the identity in relationship to political realities such as colonialism and United States interference instead of genetics.

Which brings me to Yugoslavia.

In the 1950s and ‘60s, when the country existed, a subset of Yugoslavians decided they wanted to be Mexicans in an unexpected result of Cold War policies. Having recently broken with the Soviet Union and not wanting to import either U.S. or Soviet films, the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia began showing Mexican films, which gave rise to a genre of music and style called Yu-Mex.

The trend saw Yugoslavians donning sombreros and charro suits — a byproduct of Spanish colonization — and playing what I can describe only as “Serbian mariachi music.” Some of these songs absolutely bang.

“Mexicans are very similar to Serbians,” Yu-Mex singer Slavo Perovic told BBC in 2017. “When they laugh, they laugh for real, and when they cry, they really cry.”

I can’t deny it, I feel a little proud to hear Perovic say that. And, you know what? I think he’s right. I feel a similar sentiment seeing the pachucos in Vietnam. Seeing someone find something valuable in a culture I have ties to, something that is often dismissed even by Mexicans, well, I must say, it was fun for me.

To be clear, I’m not trying to make a blanket dismissal of people’s concerns over how their cultures are handled by those unfamiliar with the nuances. But a problem I do have with “cultural appropriation” as a concept is how it flattens everything down to a simple narrative of theft and is more of an end to a conversation than a springboard for one. I think about how Black American hip-hop culture is used to generate profits while the Black people behind those same trends are demonized for them. I’m more interested in the why there than the what, less interested in ownership of imagery and more interested in how that imagery exposes political relationships between a marginalized underclass and the art they produce, and the people who value that art while devaluing the individuals who generate it.

Culture is messy, and in an increasingly globalized world, dictating how and where it spreads is incredibly difficult, if not outright impossible. My hope is that we rely less on knee-jerk reactions to cultural phenomena and ground ourselves more firmly in analysis of the immediate, substantial issues that give shape to those phenomena in the first place.

Until that time, though, please enjoy some Yu-Mex music.

JP Brammer is a columnist, author, illustrator and content creator based in Brooklyn. He is the author of ”Hola Papi: How to Come Out in a Walmart Parking Lot and Other Life Lessons,” based on his successful advice column. He has written for outlets including the Guardian, NBC News and the Washington Post. He writes a weekly column for De Los.

More to Read

The Latinx experience chronicled

Get the Latinx Files newsletter for stories that capture the multitudes within our communities.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.