- Share via

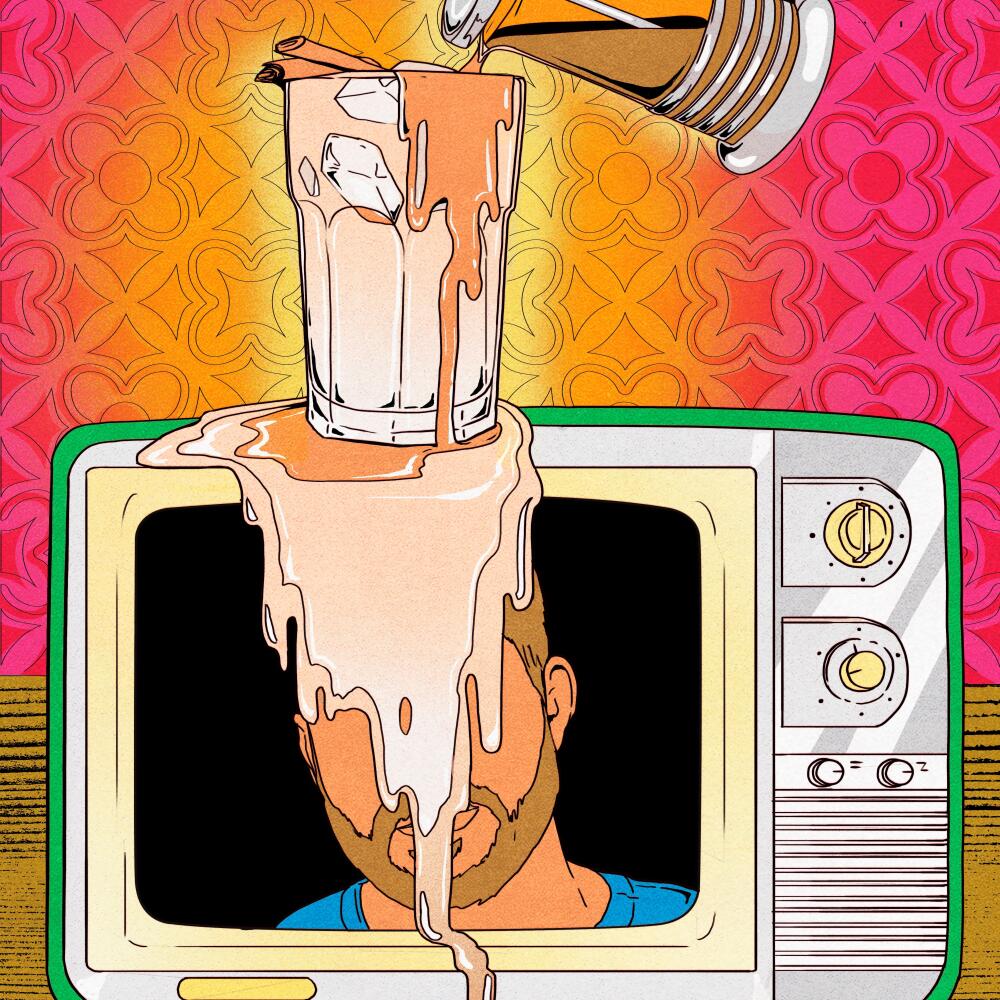

The summer before last, the summer of the horchata latte, I was in Los Angeles quite a bit. I was working on the TV adaptation of my book “¡Hola Papi!,” in a process that looked like me bringing my laptop to my showrunner’s house and hammering out things like tone, runtime and character arcs.

Doing this for a show based on a memoir is evil, upside-down therapy: The main character cares only about clicks and views. He’s not too handsome. He’s an advice columnist, but his own life is a mess. Yeowch!

My showrunner was brilliant, funny and professional. He’d worked on shows close to my heart, like “Ugly Betty.” But we had one problem: The streaming industry was seemingly only willing to greenlight projects that fell under the categories of “the next ‘Yellowstone’ ” or “basically ‘Shark Tank.’ ” Scripted shows had to be massive and preferably based on ubiquitously popular IP. In other words, we were bringing a heartfelt, 30-minute gay Latino comedy to an hourlong CGI dragon fight. We knew it was an uphill battle, even before murmurs about a strike.

The summer of the horchata latte was when things started to fall apart. My relationship was on thin ice. I couldn’t quite get my dozens of abandoned Google docs to cohere into a second book. It was becoming abundantly clear that my abuelito was dying, which was an inappropriate observation for the kid who left home for the big city to make. My mom and my sister saw him much more often than I did, and they thought he was doing all right. But every time I came home, he seemed farther away.

Dealing with all of this while painting an unflattering self-portrait in the form of a TV show was grueling. The horchata latte was a small saving grace. It’s a signature drink from La Monarca Bakery & Cafe, a Mexican eatery with multiple locations in L.A. The beverage is self-explanatory. It’s an horchata … latte. I’m not big on adding flavors to my caffeinated drinks, but I got hooked on this one. Perhaps it was the stress. I thought I deserved a little treat to start my day. Perhaps the cafe reminded me of early morning visits to the panaderia in Texas with my grandparents and my cousins. It was comforting. It reminded me of home.

Who are we protecting when we pretend white people don’t sometimes say wildly offensive things about people of color? It’s certainly not us.

Horchata latte in hand, I’d get back to it. As was the case with my book, I put a lot of pressure on myself in the process of writing the show. I hold the vestigial belief from Catholic school that suffering yields rewards, a belief that was challenged that summer after (spoiler alert) many of my pursuits, both creative and personal, ended up not panning out, despite ample suffering on all fronts. I took a lot of meetings before we actually pitched the project, and it was during these meetings that the writing on the wall became legible.

I talked to one white exec who asked me what my show would do to “correct the problems of ‘In the Heights,’ ” a movie adaptation of a stage musical about a Dominican American community in New York City that drew criticism for not having enough Afro Latino representation. I helpfully offered that my show was going to be set in rural Oklahoma, where I’m from, so the situation would probably be different but also assured him that I’d do my best anyway.

Then there were questions about making the show appealing to non-Latinos, because Latino stories tended to be “niche” and “small.” There was sage advice about not making it too gay as well, because networks with one gay show often believe they’ve hit their gay quota, and because it might alienate broader audiences. I got the hint. It was hard to sell gay stuff, and hard to sell Latino stuff, and I was asking for a lot, too much, really, in trying to sell both.

Known for her vegan hibiscus tacos, Stephanie Villegas also hosts artisanal chocolate classes where she teaches students the process using ancestral tools and techniques.

At the same time, there were expectations for the project to be incredibly diverse and to speak to several different communities all at once. It had to speak to the impossibly broad Latino experience while also being based in my own specific experience. The request was to make something that was everything to everyone, which I’ve discovered is what a lot of shows centering “diverse characters” are charged with being. I was supposed to take my story and update it, make it more palatable, and make it appeal both to Latinos and non-Latinos.

To make a long story short, I failed.

When we finally got to the pitching phase almost a year later, a phase that looked like trying to charm someone in a Zoom square who was clearly on their phone on the way to the airport, the industry was in tumult. The strike happened right after a series of kind passes.

Like the good Chicano I was raised to be, I took it on the chin and resolved to use it as motivation to do even better, to work even harder. It happens in the creative world. I don’t think I’m owed success, and there’s even something enjoyable about reworking things. I learned a lot, too. Hearing “that was well-told” from an exec after your pitch, for example, is a cue for you to jump out of the nearest window.

Politics are changing in the Rio Grande Valley. Is it the breakdown of machine politics, or gerrymandering? A return to true Mexican family values, or a betrayal of them?

Still, I can’t help but associate my time in Los Angeles with a certain miasma. It was a time of dread in my personal and professional life, and like my little TV show, both my relationship and my abuelito’s health declined. By the time all this work had been done and wasted, a year had gone by, and it was summer again, only this time I had half of what I’d started out with. I felt alone and anxious. I felt like a loser.

When I got an email asking whether I’d be interested in talking to Ricardo Cervantes, co-founder of La Monarca in Los Angeles, I instinctively said yes before remembering that I’m not really a journalist anymore. I couldn’t help it. La Monarca was a bright spot in a tough year, and I wanted to give my sincere compliments about the horchata latte to the co-founder’s face, I suppose.

Cervantes reminded me of my own family. Funny, conversational, he walked me through what it was like to try to bring the flavors he’d grown up with in Mexico to the States, and what it was like trying to balance tradition with innovation.

“We are very proud of the sweet flavor of Mexico,” he said. “We can do innovative things that preserve our flavors and cultures. We can make them more accessible, allow more people to try them, and still celebrate Mexican flavors.”

It reminded me of the delicate dance Mexican American writers and artists have to perform when telling their stories. How do you bring tradition with you into a market that often feels inherently hostile to it? How much do you negotiate on? How do you determine which parts to hold on to and which parts to let go? There are no easy answers. But one solution is an iced horchata latte.

According to the recent report from the Annenberg Inclusion Initiative at USC, Latino representation in Hollywood has not shown any meaningful growth in the last 16 years.

Cervantes also spoke about what it was like running La Monarca in the early days of the pandemic, where many of the locations became a sort of community grocery store that sold milk, eggs and toilet paper. It was an emotional subject. I thought again about my own family, about Mexican culture and how so much of what we do often takes the broader community into account. There is a sense of responsibility and obligation in our output. How does one balance that with the realities of business? With a market that seems hostile?

My bisabuelo owned a restaurant in Texas. Mexico Cafe, it was creatively named, with the subtitle “Real Mexican Food Made by Real Mexicans.” It failed. I recently came across a newspaper ad about this restaurant a week or so ago after receiving the news that my abuelo had passed away.

The last moment of genuine connection with him came just as I was heading to Los Angeles from Oklahoma during the summer of the horchata latte. He stopped me as I was walking by, squeezed my hand and said, “You did it all by yourself, didn’t you?” I wept on the plane because, no, I didn’t. Not really. I had him, a man who’d grown up dirt poor and became the first person in his family tree to go to college. I had my mom, who followed in his footsteps and became an English teacher. I had my family, and I had my community of Latino writers and artists. We do have each other. We help each other out. We make it happen.

Latino history in the U.S. is chronically under-covered in schools, according to a report from the Johns Hopkins Institute for Education Policy and UnidosUS, an advocacy organization.

As I work on a movie script based on a chapter from “¡Hola Papi!,” I think back to my failures, to my abuelo and, of course, to the horchata latte at La Monarca, which defines an era in my life the way a certain scent or taste can define spans of time in the memory. I see in it a story that looks like mine, and like the story of so many other Mexican Americans trying to make something worthwhile in the world. There’s some tradition and some innovation.

That’s how we do things. We carry the things we grew up with, and we put our own twist on them. We adapt, we change, we edit, we fail, we get told “no,” and then we go back to the drawing board and we try again, both for ourselves and for our families, and, sometimes, even for people we haven’t met.

Sometimes it works out, and sometimes it doesn’t. But it’s a sweet thought, either way.

JP Brammer is a columnist, author, illustrator and content creator based in Brooklyn. He is the author of ”Hola Papi: How to Come Out in a Walmart Parking Lot and Other Life Lessons,” based on his successful advice column. He has written for outlets that include the Guardian, NBC News and the Washington Post. He writes a weekly column for De Los.

More to Read

The Latinx experience chronicled

Get the Latinx Files newsletter for stories that capture the multitudes within our communities.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.