- Share via

It reliably surprises people to hear that Latinos rank climate change near the top of their concerns, right up there with the economy and immigration. A staggering 81% of Latinos in the U.S. consider addressing climate change to be a priority compared to 61% of non-Latinos, according to the Pew Research Center.

There are reasons for this, which I’ll get into. But more immediately, in a world plagued with disasters, many of which offer glimpses of atrocities to come, it’s time to take Latinos’ lead on this issue as we prepare for a perilous future.

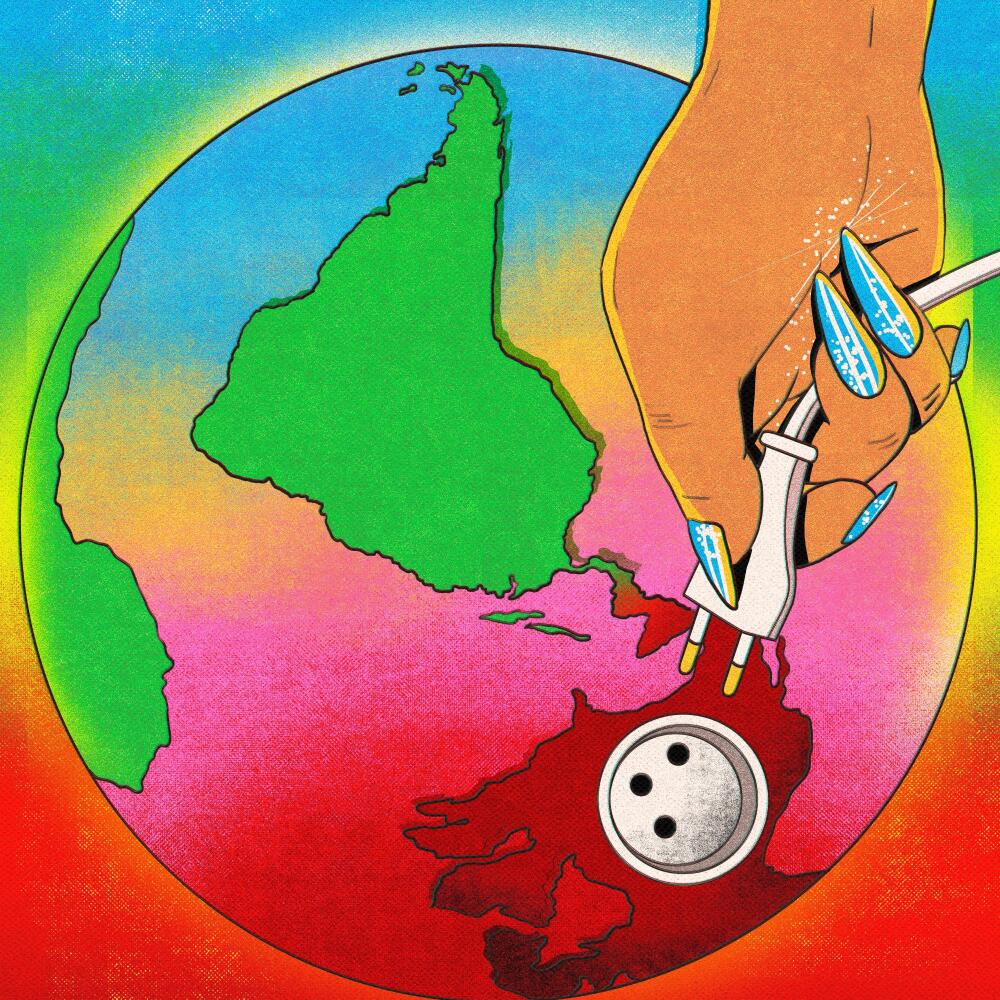

A recent development that puts this into urgent perspective is Big Oil’s disinformation push targeting Latinos in California.

Earlier this year, the Western States Petroleum Assn., a lobbying group, initiated the Levanta Tu Voz, or “Raise Your Voice,” campaign. The $1-million project saw Spanish-language ads drumming up anxieties over zero-emission vehicles and equipment, among other things, in a blatant attempt to turn Latinos against the idea of green technology.

José Olivarez curates the De Los Latino poetry series where poets reflect on their relationship with nature.

As The Times’ editorial board astutely put it, “We shouldn’t fall for another delay tactic by an industry with a history of disgraceful and deceptive behavior.”

In targeting Latinos, the oil industry is seeking to weaken a major source of support for renewable energy. Cynically, the campaign preys on a very real phenomenon: Latinos going unheard and unheeded by their government.

It’s especially callous considering that the reason Latinos place such importance on the issue of climate change is because they are among the people most likely to be harmed by its effects. They are more likely than non-Latino white people to experience heat waves, floods, hurricanes and pollution.

Latinos put climate change so high on their list of concerns because it is based in the material reality of their communities.

Texas legislator Armando Walle went viral after his impassioned and profanity-laced outburst against an anti-immigrant state bill went viral.

Prominent examples include the aftermath of Hurricane Maria in Puerto Rico in 2017, a disastrous storm that to this day sees Puerto Ricans calling for a reliable, renewable electric grid on the island.

There are similar stories out of Texas, where hurricanes have made landfall and where winter storms have brought entire cities to their knees. Scenes from these emergencies have become part of the general, bleak mosaic of everyday life over the past several years: migrant caravans, displaced refugees, wars, the backsliding of democracy, crisis after crisis.

To some, these harrowing events may appear scattershot — individual pieces of evidence of general unrest or of society falling apart. But in reality, they are intimately linked, and patterns emerge when we consider them in the collective, patterns that Latinos, in particular, should be concerned by.

It’s not just the warming planet that makes climate change such an urgent issue for Latinos. We should acknowledge that we stand on the precipice of mass climate migrations, a phenomenon that coincides with rising xenophobia and reactionary governments harnessing that anxiety to stay in power.

Recent statistics out of Texas show Latinos outnumbering non-Latino white people in the state. What does that mean, and how do the implications show how we view Latinos in this country?

A common thread through many of these calamities is wealthy Western nations capitalizing on the labor and resources of the Global South, then turning a blind eye when their practices create political, economic or environmental instability in those regions.

This holds true for the climate crisis as well.

The future, it seems, is one where the condition of being a migrant is increasingly common, while a willingness to acknowledge the root cause of why those people are migrating is vanishingly rare. The pundit class is eager to assign the blame on primitivity or barbarity in the cultures associated with the people seeking more hospitable environments.

This is a narrative that politically conscious Latinos recognize all too well, both within the United States and without. It brings to mind the national focus on separated families at the border in 2018, which inspired calls to abolish the U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement agency, or sporadic fears of migrant caravans.

A new Brookings Metro report shows that white households in New York hold 40 times the wealth of Latino households.

Climate change isn’t as simple as “the Earth will get hotter, and people will either drown in the rising sea or die from heat stroke.” It’s more complex than that because, in addition to the inherent environmental dangers, there is also a political structure in place that is not built to minimize suffering and maximize saving lives.

It is instead a system designed for hoarding, for justifying death and squalor in the name of maintaining hegemony.

It’s a chilling thought, but it’s important to remember that these are systems we designed, and that means we can change them. Latinos didn’t choose to live on the front lines of climate change, and it’s sad to see the circumstances that led to climate change being ranked as such a pressing matter. But it also gives me hope to see politically engaged Latinos of many different backgrounds continue to call attention to the problem, even as well-funded groups try to convince them otherwise.

“Levanta Tu Voz,” as I said before, is a cynical name for a misinformation campaign. But it gets one thing right. Latinos should be heard. Will anyone in power listen before it’s too late?

John Paul Brammer is a columnist, author, illustrator and content creator based in Brooklyn. He is the author of ”Hola Papi: How to Come Out in a Walmart Parking Lot and Other Life Lessons” based on his successful advice column. He has written for outlets like the Guardian, NBC News and the Washington Post. He writes a weekly column for De Los.

More to Read

The Latinx experience chronicled

Get the Latinx Files newsletter for stories that capture the multitudes within our communities.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.