- Share via

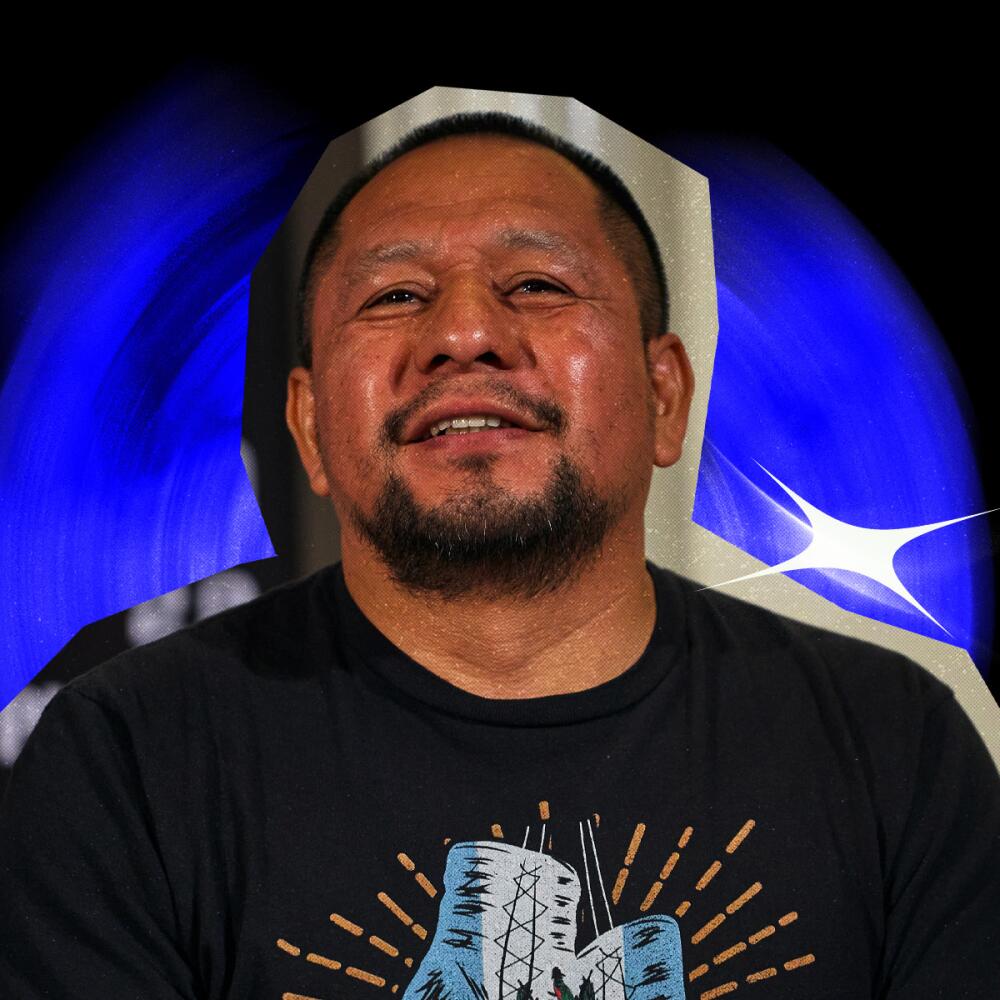

Esaú Diéguez, a national amateur boxing champion from Guatemala, remembers arriving in the United States in the 1990s at the age of 20 with a very simple plan.

He was going to find a gym in Los Angeles and start training in hopes of becoming a professional boxer. But boxing is a business, and a cruel one at times. He found that out very quickly.

At the start of his career, he earned a decent living fighting opponents from the same promotional company, but other times he would end up fighting future world champions with very little preparation. Soon, the phone stopped ringing.

El entrenador principal McIntyre y su asistente Diéguez estarán en la esquina de Crawford cuando este enfrente a Errol Spence Jr. el sábado, 29 de julio, en Las Vegas

In Los Angeles, landing a job at a boxing gym was a competitive endeavor, and it was made doubly hard by Diéguez’s status as an undocumented immigrant.

“When you get to this country, you think things are going to be easy,” Diéguez said. “The first thing they asked me about was my papers, and my dream died right there. But I kept fighting and fighting.”

After seven years living in Los Angeles, Diéguez, 51, decided to move to Omaha in 1999 to try and keep his professional boxing dreams alive. But after four years, he was able to land only one fight and his overall record had an ugly streak of six straight losses. He worked at Quality Pork International as a meat packer for 13 years to support his family.

He befriended Brian McIntyre, who had also pursued a professional boxing career, and joined his gym, B&B Sports Academy, to help train young fighters, many of them Latino.

But everything changed in 2001 when a kid named Terence Crawford walked through the gym’s doors.

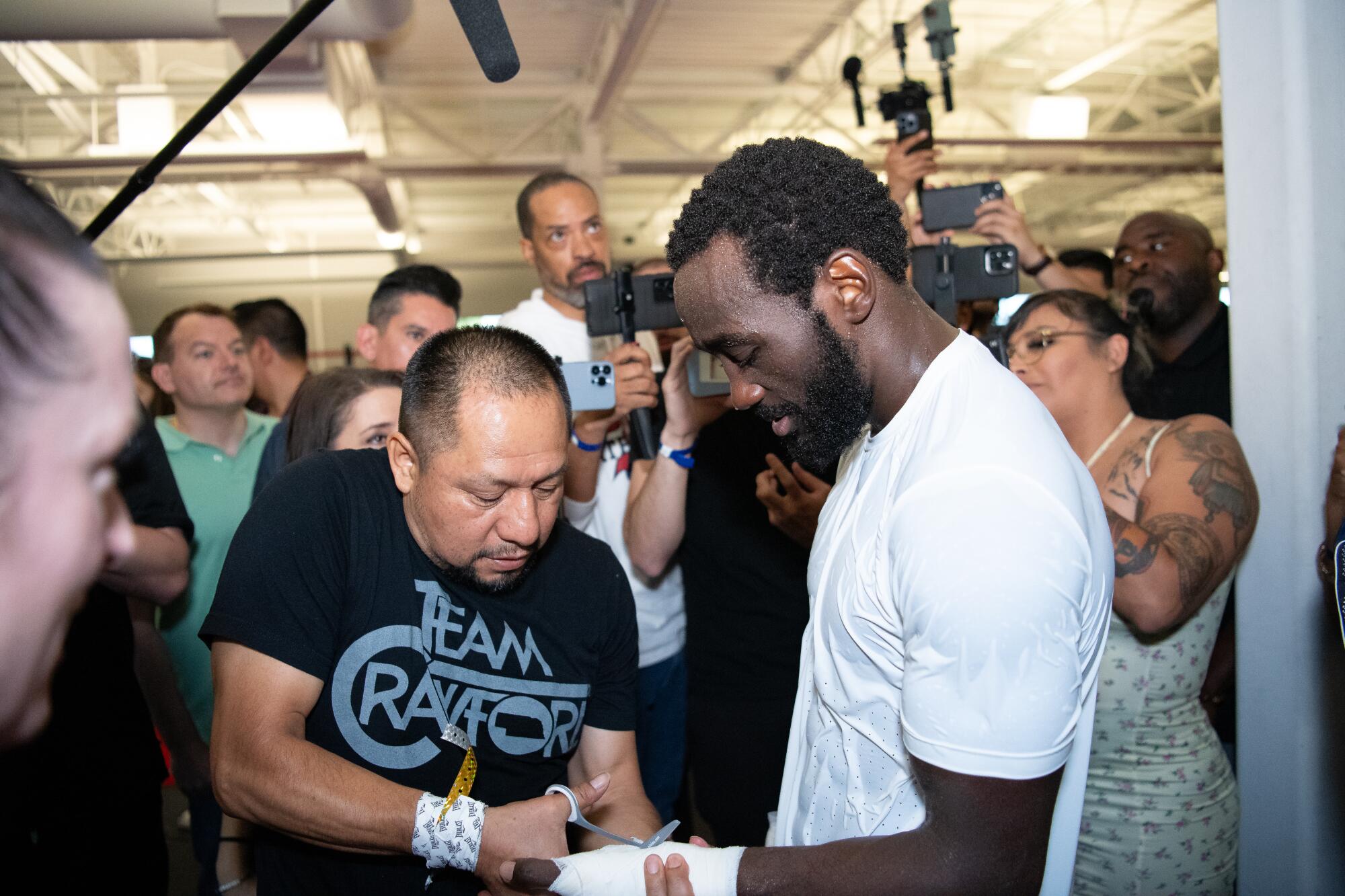

McIntyre, with Diéguez’s help, started training Crawford, and two decades later, that 14-year-old boy has become one of the best boxers in the world and one of the first names that appears atop most pound-for–pound lists.

Crawford has won three world titles in three different weight classes and is currently the owner of the World Boxing Organization’s welterweight belt.

The people of New Mexico were the first victims of the atomic bomb, the result of the Manhattan Project’s Trinity Test on July 16, 1945.

McIntyre and Diéguez will be in Crawford’s (39-0, 30 KO) corner when he faces off with Errol Spence Jr. (28-0, 22 KOs) at T-Mobile Arena in Las Vegas on Saturday in one of the biggest fights of the last decade. The winner will become the first undisputed welterweight champion since the advent of the four title belts.

Diéguez has worked with Crawford since the boxer was a teenager and even was his sparring partner early in his career, when he was showing signs of talent. He had sparred with other quality fighters, but Diéguez knew that Crawford was going to be special.

Crawford smiled when recalling his time sparring with his much older trainer.

“I was just a kid when we sparred,” Crawford said. “I remember he would hit me hard. I was a bit bigger than him but he had all this experience.”

In the run-up to the Spence fight, McIntyre and Crawford have worked on the fight plan, while Diéguez has been in charge of the daily workouts. Crawford has also relied on Diéguez’s insights outside of the ring. He has called Diéguez a “man of God” who has helped him deal with his newfound riches.

“I come from a very small town and I never thought I’d get this far, but God has been very good to me and has blessed me,” Diéguez said.

On Saturday, Crawford has the opportunity to establish himself as the best pound-for-pound fighter in boxing. If he beats Spence, the spotlight will also be on his quiet Guatemalan trainer.

More to Read

The Latinx experience chronicled

Get the Latinx Files newsletter for stories that capture the multitudes within our communities.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.