- Share via

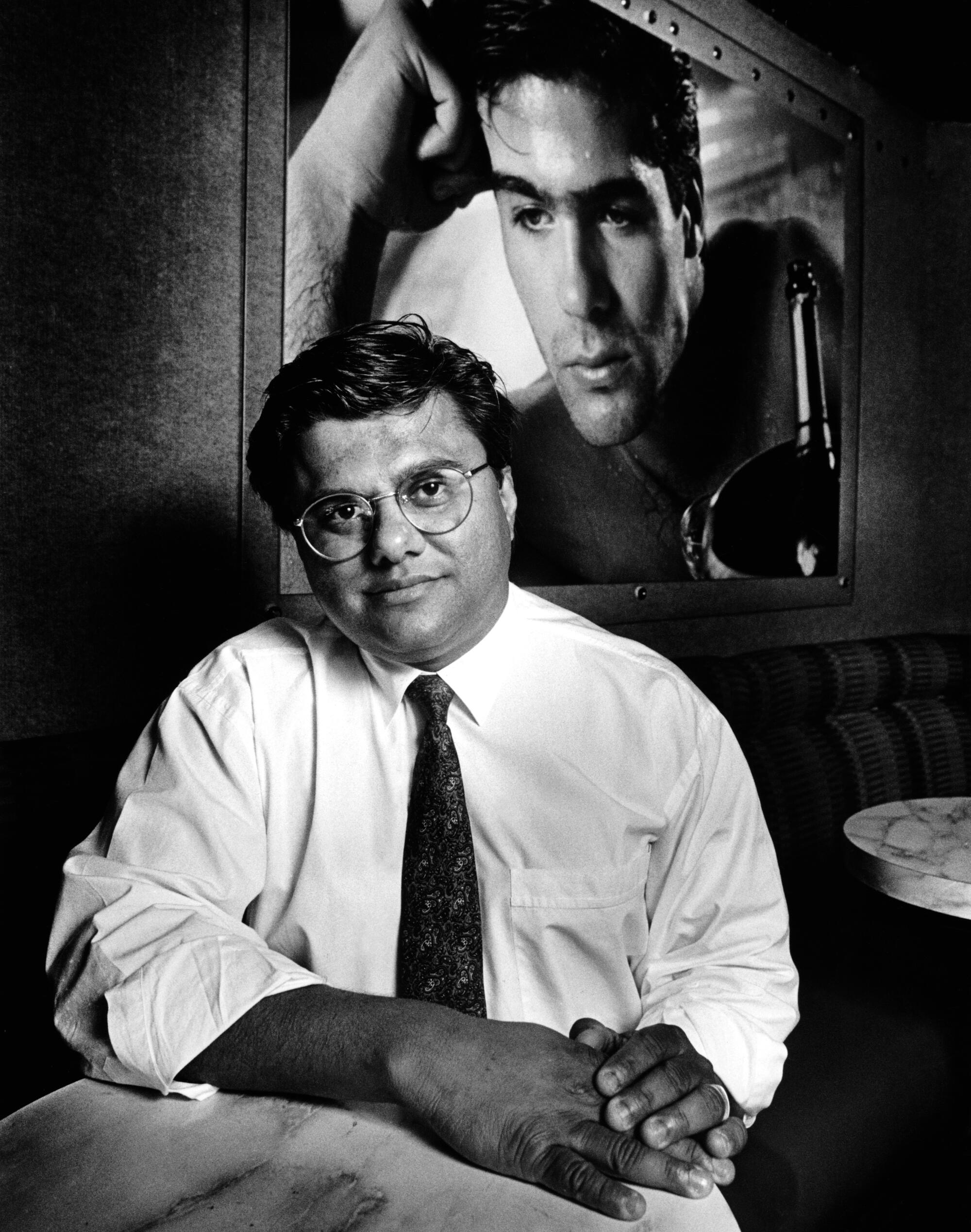

The father of Chippendales was in his 30s when he launched what would become a multimillion-dollar empire of jacked, bow-tied male strippers.

Hundreds of women gawked as muscular men stripped down to g-strings in Somen “Steve” Banerjee’s L.A.-based club. Before long, Banerjee’s dancers were touring like rock stars, he‘d opened a club in New York, and a “Saturday Night Live” sketch featured Patrick Swayze and Chris Farley as aspiring Chippendales performers.

Then, around 15 years after the story began, Banerjee’s reign ended abruptly. Law enforcement investigated allegations that he’d plotted to murder former employees and was linked to a homicide carried out by a hit man. In 1994, after pleading guilty to a racketeering charge that included soliciting a murder and attempted arson, Banerjee killed himself.

The inheritance he left his children: legal battles, family drama and outlandish theories.

Banerjee’s son, who legally changed his name from Christian Banerjee to Chris Bane, believes he is the rightful heir to his father’s business. Chippendales USA LLC sued the 34-year-old Bane in federal court last year, accusing him of using the Chippendales trademark without permission. In a motion responding to the company’s lawsuit, Bane insinuated that Chippendales wants to do him harm. On social media, he says it outright.

The company has denied the allegation.

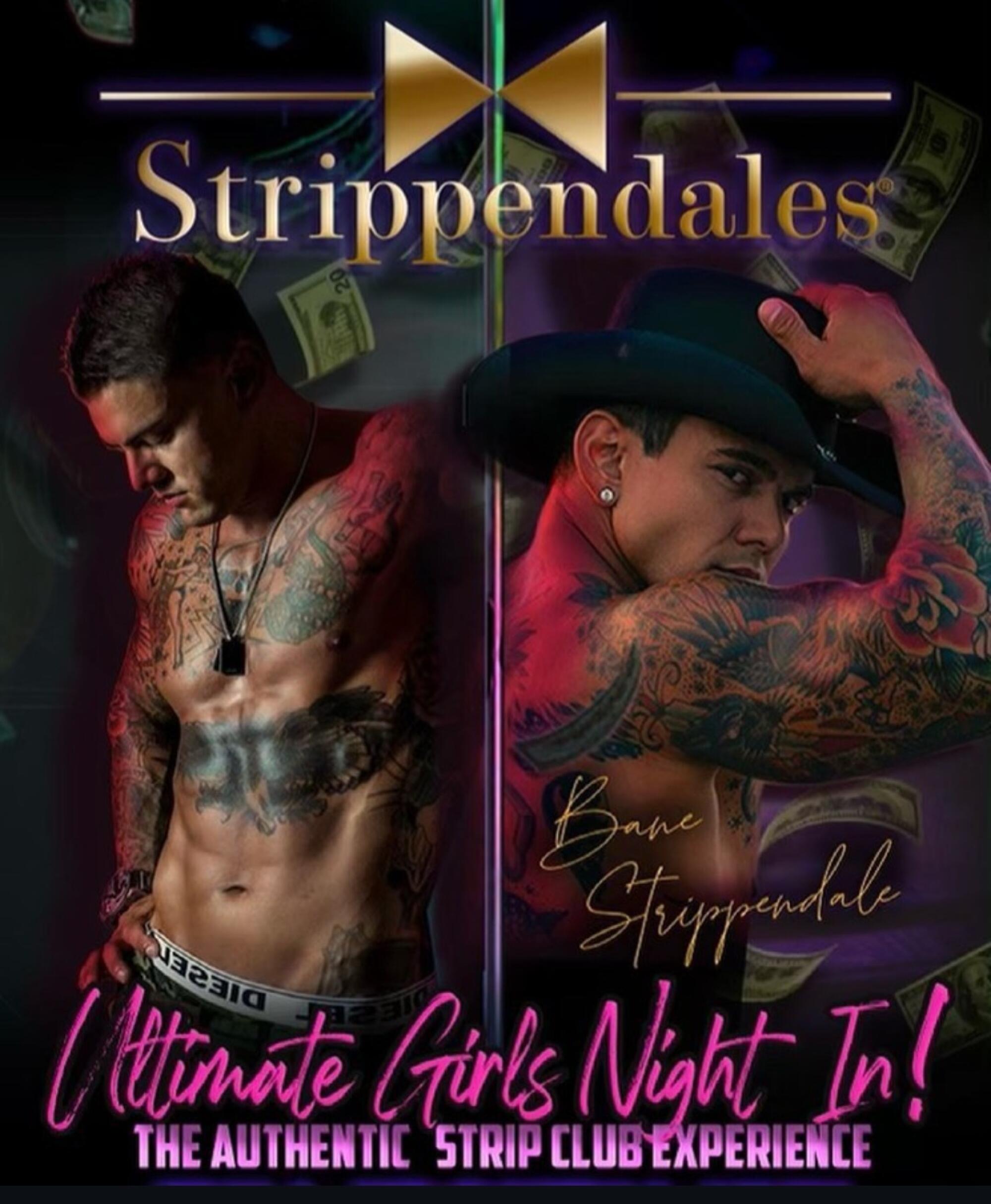

The latest drama began after Bane launched a competing enterprise. And had the nerve to call it Strippendales.

A stripping enterprise

The half-naked man places a napkin on a woman’s lap, his abs the center of attention in the Instagram video. As he pops a morsel into her mouth, there’s a flash of a black bow tie and white cuffs.

Another woman spanks his jeans-clad butt as he rides her lap. A blond with a pink “Bride” sash rains $100 bills down on him.

“Here at Strippendales Not Only Do We Know How To Striptease, We Know How To Please!” the video caption reads. “The Hottest Male Strippers & More!”

Bane — who declined to be interviewed by The Times, citing a contract with a production company — registered Strippendales with the state of California in 2020 as the pandemic wreaked havoc around the world.

On a website where the pink-and-black color scheme resembles Chippendales’ online presence, Bane offers bookings in homes, backyards and other venues. The first entertainer listed is “Hollywood,” aka Bane himself. He is shirtless, heavily tattooed, his chin propped on his right fist, his left hand resting on a camo-clad leg. (Due to medical issues, Bane is currently able to make only limited appearances and performances, according to his business partner, Amy Le Chet).

A blurb on the website says Bane, who is 6 feet 3 and 250 pounds, has “followed in his father’s footsteps with his innovative venture.”

Not only did Bane go into the family business but, like his father, he has faced criminal charges.

Among them: burglary, grand theft auto, forgery, unlawfully owning and possessing a firearm and being a felon in possession of a firearm. Bane pleaded guilty to the burglary, forgery and grand theft auto charges, according to L.A. County Superior Court records, although he insists he pleaded no contest.

In 2012, he pleaded no contest to unlawfully owning and possessing a firearm and being a felon in possession of a firearm. The following year, Bane pleaded no contest to assault tied to headbutting in the face a woman he was dating. Le Chet called it a setup and said Bane had acted in self-defense. She said Bane served 18 months in prison on the assault and firearms charges.

Le Chet said Bane is filing a petition to dismiss his convictions.

In a court filing replying to a Chippendales motion, Bane painted a bleak picture of his life. In 2022, he ruptured both of his pectorals and has undergone four surgeries. He said he became homeless and lived in his 2007 Chevy Suburban and the homes of friends, and various hotels, short-term and daily rentals found on Craigslist.

But he had vowed to make a name for himself, envisioning an enterprise bigger and better than his dad’s.

”... [O]thers won’t go to the lengths that I will, and that’s why nobody will remember their name, and my name will go on forever in male stripping history, Apple don’t fall far from the tree,” Bane wrote in a Facebook post in May 2023.

Strippendales, however, is a far cry from the empire his father built.

‘Sex fantasy just for women’

It all started with Destiny II.

Banerjee, who was born in India, bought the Westside disco bar in 1975. He later renamed the club for its Chippendale-style furniture, ornate pieces inspired by the 18th century cabinetmaker.

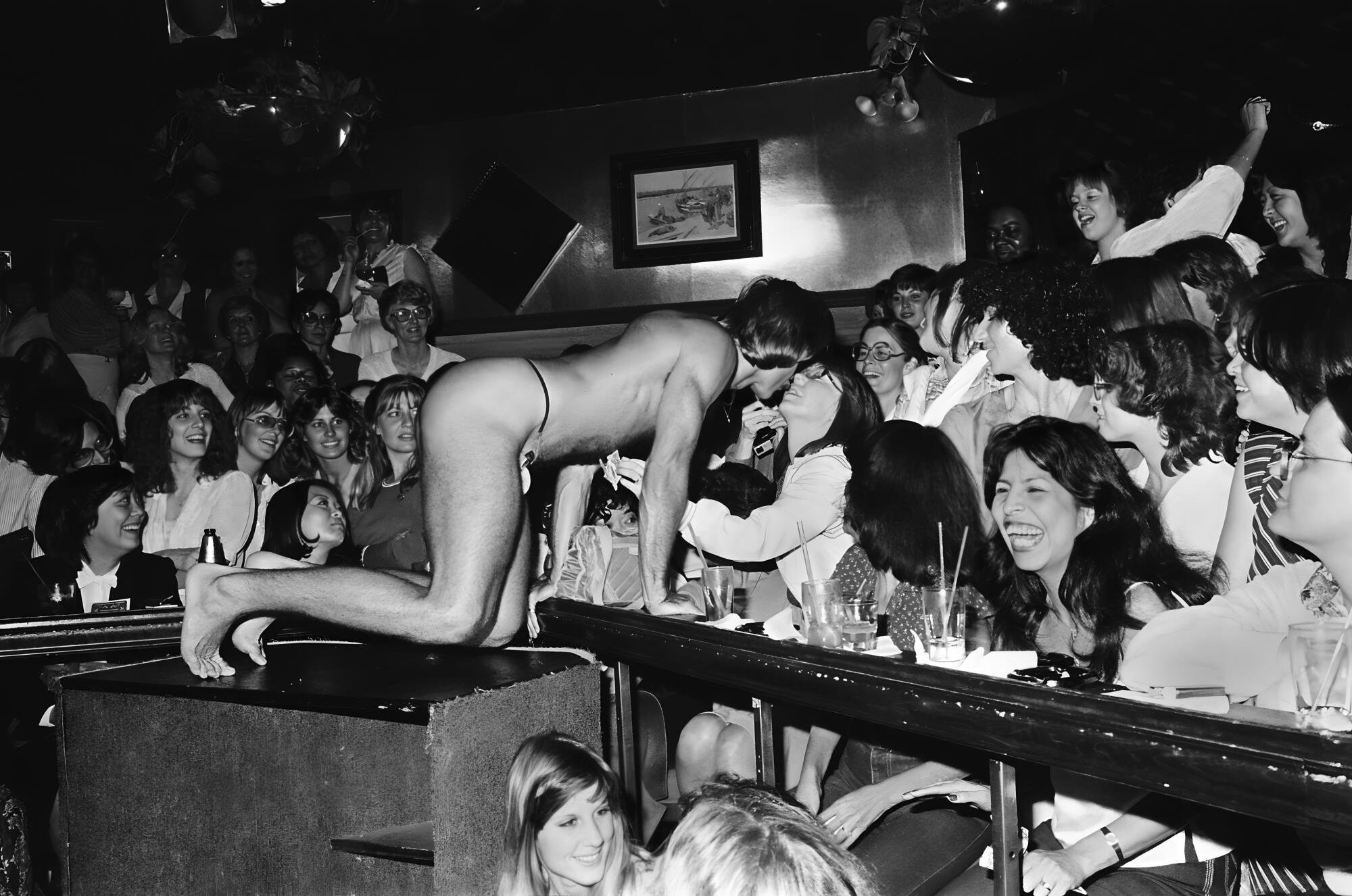

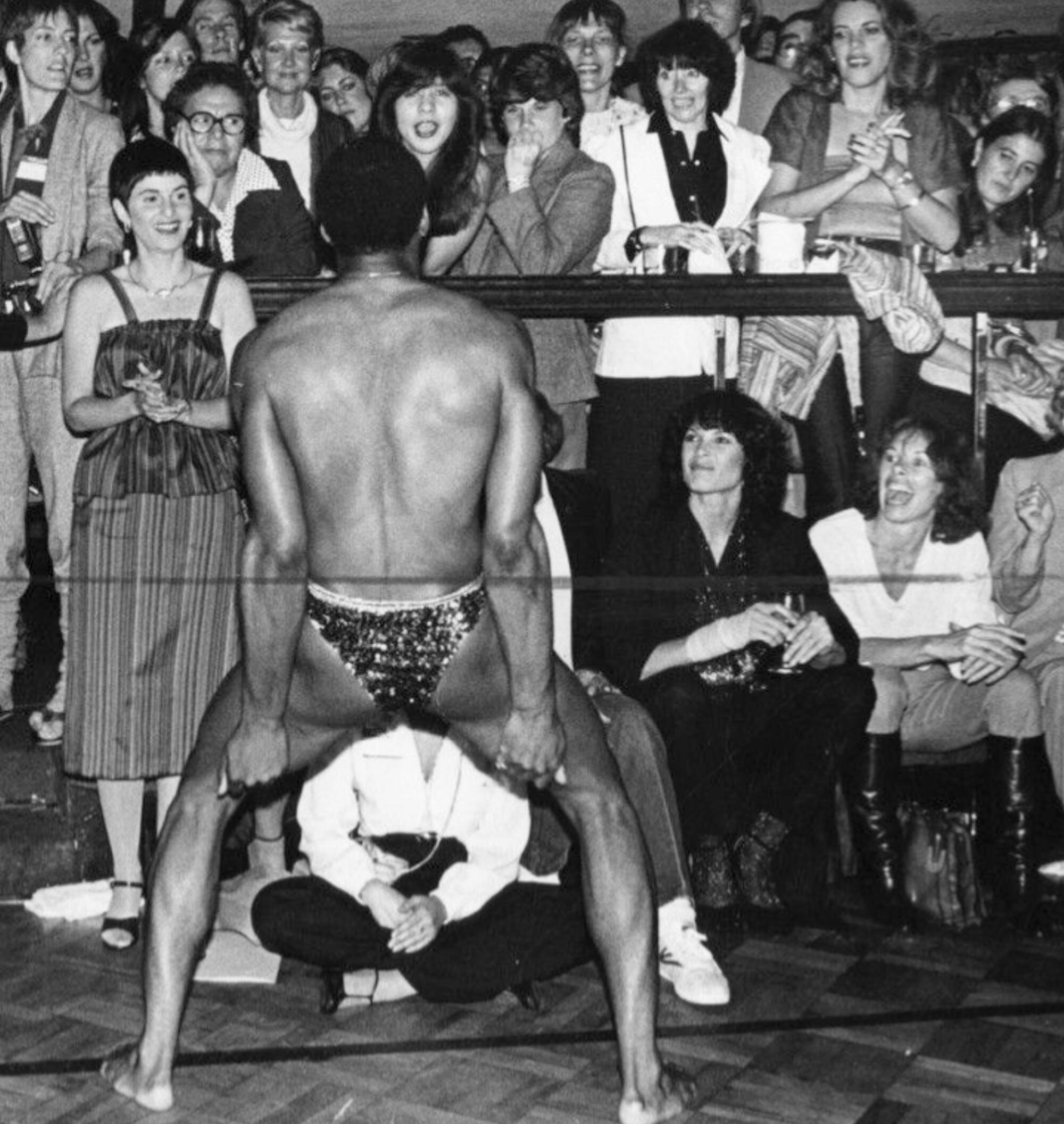

But the disco days of “Saturday Night Fever” soon passed, and Banerjee had to adapt. He hired Frank Sinatra’s son to sing in the club. Women mud-wrestled. But it was the male strippers who, in 1979, changed the game.

Only women were allowed inside for the performances, shouting at men to “take it off” and getting a kiss for a tip. Customers were soon lining up around the block. Banerjee reportedly got permission from Hugh Hefner to adapt the Playboy Bunny costume for men. They worked bare-chested, in spandex, wearing cuffs, collars — and a bow tie.

Even Gloria Allred went to the club, throwing a controversial feminist fundraiser there in 1980. “I think the women’s movement is against sexism, but not necessarily against sex,” she told a Times reporter. (She later sued Chippendales, alleging that men were unlawfully barred from the show.)

As Banerjee told a Times reporter in 1981, the club was “creating a sex fantasy just for women.” Soon there was a Chippendales calendar, playing cards and the club in New York. By the time Banerjee married his wife, Irene, in 1984, Chippendales’ revenue had reportedly soared to $20 million a year.

Banerjee and Irene had their first child, Lindsay, in 1985. Banerjee would wave dollar bills in the baby’s face and say: “money,” recalled Bruce Nahin, a former lawyer for Chippendales. Banerjee joked, Nahin said, that it was Lindsay’s first word.

Bane followed in 1990, the same year “SNL” featured the ripped Swayze and portly Farley auditioning for a Chippendales spot.

Nahin described Banerjee as an “absent” father. He’d work 18-hour days, trying to build his empire. “He thought he’d be the next Hugh Hefner,” Nahin said in a recent interview.

But lawsuits began piling up. There were personal injury cases and charges of overcrowding at the club and discrimination against men. Banerjee lost close to $1 million when the 1987 Chippendales calendar was printed with 31 days for every month. That year, Chippendales’ parent company, founded and owned by Banerjee, filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection.

Around that same time, Nick De Noia — a business associate who had helped revamp the Chippendales show and obtained the touring rights from Banerjee — was shot to death in his New York office. Family and friends suspected Banerjee was behind the murder, according to government documents reviewed by The Times. With the case unsolved, the Chippendales founder bought the touring rights from the dead man’s estate.

Despite the original L.A. club’s 1988 closure, the Chippendales dancers continued performing across the country and abroad. Banerjee continued making headlines, with Chippendales dubbed the “hottest all-male dance troupe.”

Everything came crashing down when FBI agents arrested Banerjee outside Chippendales’ headquarters in Santa Monica on Sept. 2, 1993, on charges of conspiring to kill three former business associates who had left to join a rival dance revue.

A month later, a federal grand jury in Los Angeles expanded the charges and indicted Banerjee for De Noia’s murder and attempted arson for allegedly trying to have competing nightclubs burned down.

“Banerjee was this ruthless person who would stop at nothing to get what he wanted,” said Scott Garriola, a retired FBI agent who worked the case.

Banerjee pleaded guilty in federal court to the racketeering charge, which included arranging De Noia’s murder and attempted arson. As part of the plea deal, reviewed by The Times, Banerjee agreed to forfeit his interest in Chippendales and its parent company, Easebe Enterprises Inc.

Facing a 26-year prison sentence, he killed himself in his jail cell on Oct. 24, 1994. He was 48. Because Banerjee died before he was sentenced, Garriola said in a recent interview, the government couldn’t seize Chippendales.

Lindsay and Bane were 9 and 4 years old when their father died. Not long after, breast cancer ravaged their mother. She became bedridden and was placed in hospice care in their Playa del Rey home. She died in February 2001.

Before her death, according to a lawyer representing Irene Banerjee’s sister and brother-in-law, she agreed to sell Chippendales and its trademarks.

That sale has become a point of legal dispute.

The legal battle

The courtroom drama began when a man named Jesse Banerjee filed a petition in L.A. County Superior Court in 2017 to administer the founder’s estate. Jesse identified himself in the petition as Banerjee’s eldest son and later said he hadn’t received his rightful inheritance.

In his book, “Chippendales True Crime Story,” Jesse says his mom, an immigrant from Mexico, met Banerjee in a party zone for immigrants in downtown L.A. The couple, he wrote, split up when he was 3 years old, but he and Banerjee maintained a relationship.

In a court filing contesting the petition, Lindsay Banerjee asserted that “no one in her family” had heard of Jesse. Jack Osborn, an attorney for Lindsay and her aunt and uncle, said Lindsay withdrew a competing petition to be appointed as administrator because “there’s really nothing in Steve’s estate to be probated.”

Jesse was appointed administrator of the estate. He claimed in probate court that Irene had fraudulently sold the Chippendales trademark. He petitioned the probate court to get it placed back into the estate, a case that was later moved to federal court, becoming Jesse Banerjee vs. Chippendales USA LLC.

A string of lawsuits followed.

In a suit against Jesse, Chippendales USA, LLC — a Delaware limited liability company composed of four unidentified members — pointed to his use of the Chippendales mark and the bow tie design on his website and the sale of infringing merchandise. The lawyers noted that on social media, Jesse called himself the “Chippendales Heir.”

“I’m telling my story,” Jesse said in an interview with The Times. “If that makes me an infringer, that’s insane.”

Last year, a federal judge dismissed Jesse’s suit against Chippendales, citing his failure to state a valid claim and the statute of limitations. The same judge ordered Jesse to pay Chippendales $11,200 in attorney fees and damages for trademark infringement and counterfeiting.

“The judge was biased and ignored everything I said,” Jesse said. He added that he’s currently appealing the ruling.

In a suit against Bane, Chippendales’ lawyers accused Banerjee’s recognized son of adopting a version of the company’s bow-tie design mark “in a clear effort to capitalize on the fame and goodwill” of the original beefcake enterprise. They asked the judge to order Bane to stop interfering with the company’s ownership or use of its trademarks, “including by alleging ownership of the CHIPPENDALES Trademarks, brand, or company in commercial advertising, marketing, or promotion.”

In a motion to set aside Chippendales’ request for a default judgment, Bane wrote that, in November, as he was driving, the front of his car exploded and caught fire. His vehicle, he wrote, spun multiple times and hit the steel barrier “next to a deadly cliff.”

“At this time, Chippendales’ actions have become suspect with their questionable activities,” the filing read. “They have knowledge and are monitoring the location of Chris Bane through their private investigator.”

The private investigator’s timeline of following Bane, the filing states, is “consistent with the attacks on the life of Chris Bane.”

Bane’s Instagram bio was more direct: “chippendales does not own chippendales, they tried to kill me ... because they cannot prove they own it in court! Chippendales ain’t slick!”

In response to Bane’s motion, Chippendales’ lawyers said that he “did not and cannot submit any evidence supporting his audacious speculations that Chippendales has in any way affected his safety.”

Responding in all capital letters to a list of questions, a lawyer for Chippendales called Bane’s allegations that the company is trying to kill him “COMPLETELY FALSE.”

Bane claims on social media that De Noia is alive and that his father was set up. That his aunt and uncle, Helen and Brad Maryman, stole control of his mother’s estate and took millions of dollars from him. That he’s the heir to Chippendales and Jesse is a straw man.

Osborn, who represents the Marymans, denied Bane’s claims against his clients.

“It’s kind of heartbreaking for Brad and Helen because they love both Christian and Lindsay,” Osborn said. “He does continue to say really, really troubling things on social media about them. They don’t respond, but it is hurtful.”

The federal and probate cases are ongoing. In an emailed response, a lawyer for Chippendales said they are confident the company will prevail against Bane.

Chippendales live

A spotlight in the darkened theater illuminated the eight men on stage as, one by one, they pulled open black zip-up shirts to reveal washboard abs. The audience’s screams of approval at times drowned out the soundtrack, Billie Eilish’s “bad guy.”

The show began as two of the men moved in choreographed steps, body-rolled, swiveled their heads and puffed out their chests. Behind them, on a raised platform, the rest of the crew trooped in — wearing cuffs, collars and their signature bow ties.

“Ladies and gentleman, we are the No. 1 male revue in the world,” the MC boomed into the microphone. “The men of Chippendales.”

About 100 women — and a few men — watched, mouths agape, as the dancers tore their Fruit of the Loom tanks apart and ripped off their underwear, leaving only penis socks. It was a recent Friday night at the Las Vegas Chippendales Theatre. Women celebrating birthdays or impending nuptials, marked by crowns and pink sashes, were pulled on stage for lap dances, their hands directed to available bare flesh.

Although a sizable crowd had navigated to the performance space tucked away inside the Rio Hotel & Casino, it was a far cry from the number that had once packed into Banerjee’s L.A. club. Competition has grown from other male revues such as Thunder From Down Under and Magic Mike Live.

Even so, the company said in its lawsuit against Bane, Chippendales’ productions are seen by more than 2 million people worldwide each year.

In the theater, the men become whomever the crowd desires: An almost nude motorcyclist, wearing black gloves and shielding his penis with a helmet. A shirtless rock star, in red pants and boots, playing “Sweet Child O’ Mine” on an electric guitar. Construction workers in dirty white shirts, blue jeans and tan work boots (the orange construction sign nearby reads: CAUTION EXTREMELY HOT).

All are chiseled — according to a Chippendales’ fact sheet, the organization’s 20 exclusive cast members will spend a collective 59,725 hours a year in the gym.

Tara Gallichan, who traveled from Canada on a girls’ trip, said that even though she’s married she enjoyed the show guilt-free.

“I don’t know how to explain it,” the 34-year-old said. “It’s something about getting away and that fantasy and that temptation without acting or crossing a line.”

Legal dramas swirl around Chippendales, but on this night, Banerjee’s vision of a sex fantasy for women was alive and well.

More to Read

Sign up for This Evening's Big Stories

Catch up on the day with the 7 biggest L.A. Times stories in your inbox every weekday evening.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.