- Share via

She was one of Charles Manson’s earliest disciples, a waif-like flower child who rhapsodized about LSD and redwood trees, and one day in 1975 she brought a loaded gun to see the president.

Lynette “Squeaky” Fromme, 26, had been living in a $100-a-month attic apartment in an old Victorian on P Street, a few blocks from the Sacramento statehouse. She had moved to the city to be close to Manson, who for a time had been incarcerated in nearby Folsom for the home-invasion murders in Los Angeles that made him infamous.

Fromme did not appear to harbor any specific animus toward President Ford, but he represented an establishment she and the Manson clan despised. She had been distributing apocalyptic news releases. That summer, speaking to the Associated Press, she promised carnage while invoking two of Manson’s crime scenes and a massacre in Vietnam.

In this series, Christopher Goffard revisits old crimes in Los Angeles and beyond, from the famous to the forgotten, the consequential to the obscure, diving into archives and the memories of those who were there.

“If Nixon’s reality — wearing a new Ford face — continues to run the country against the law, our homes will be bloodier than the Tate-LaBianca houses and My Lai put together,” she said.

Then, as now, the Secret Service had a long list of people who posed a potential threat to the president. Despite her menacing rhetoric, Fromme’s name did not make the list.

She was waiting quietly near an orange tree in Capitol Park around 10 a.m. on Sept. 5, wearing a hand-sewn Red Riding Hood-style cloak that was supposed to symbolize a newly ascetic lifestyle of sacrifice and activism. On her leg, beneath her dress, was a jury-rigged holster with a borrowed .45 handgun that had been developed for the military.

Having just spoken to a group of business leaders at breakfast, Ford left the Senator Hotel and crossed the street to the park. He was going to see Gov. Jerry Brown at his office, a walk of maybe 150 yards. Hundreds of people had gathered to catch a glimpse of him and shake his hand.

Karen Skelton, then 14, had ditched school for a look at the president. She recalls the crowd was three or four people deep, and Fromme was a few feet ahead of her, to the right.

“I thought she was a little odd, because she was in this red robe,” Skelton told The Times in a recent interview. “At one point she sort of looked around and looked up, and said, ‘Oh, what a beautiful day.’”

The president had opted against traveling to the Capitol in his armored car, and Larry Buendorf, a 37-year-old Secret Service agent, was part of the security detail accompanying him on foot.

“Rather than a motorcade, he said, ‘I think I’ll just walk,’” Buendorf recalled this month. “It was unplanned, so everybody hustled to get things in place as best we could. A lot of people lined up along the sidewalk. He was just walking along, shaking hands. I was right at his shoulder, to make sure nobody held on too long and make sure nobody took his watch. My concentration was on the hands that were reaching out to him.”

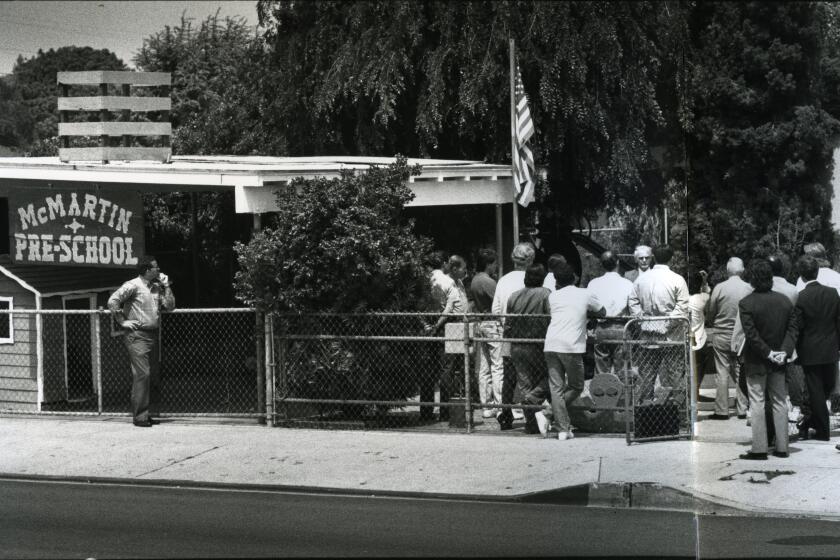

The McMartin Preschool trial ended with zero convictions. “McMartin” became a byword for social contagion, hysteria and the epic failure of trusted institutions: law enforcement, courts, the child-therapy establishment and the media.

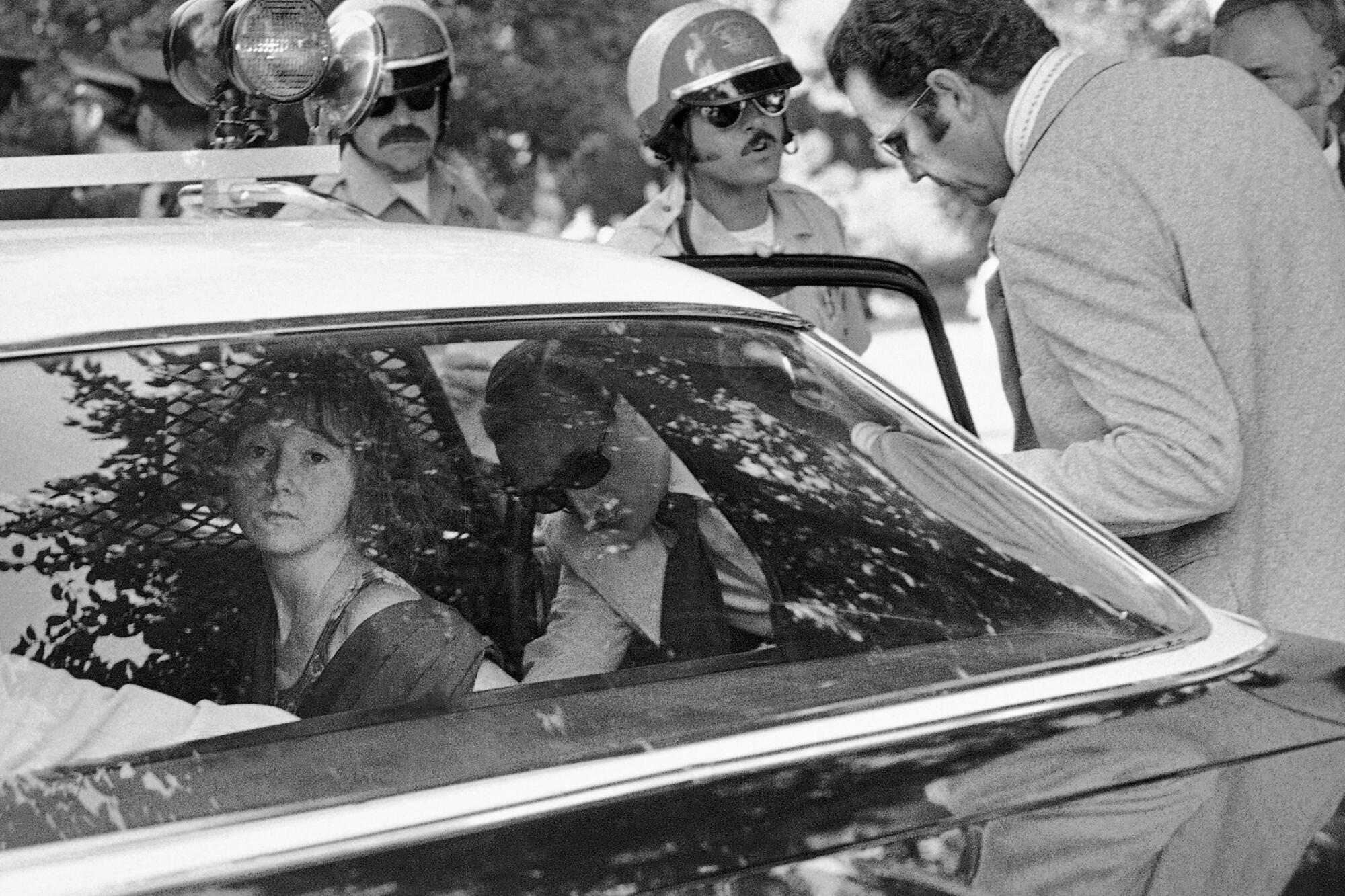

That is when he saw the .45 in Fromme’s hand, pointed at the president. He stepped in front of Ford and grabbed the gun. Ford was hustled to safety, Fromme thrown up against a tree and handcuffed. Witnesses heard her exclaiming, “It didn’t go off” and “He’s not a public servant.”

Somehow, Buendorf’s hand was cut. He’s not sure exactly how.

Investigators would find no bullet in the gun’s chamber, but four in the clip.

“You pull the slide back, and it chambers a round. If she had had one in the chamber already, I don’t think I would have made it. I think it would have gone through me and the president,” Buendorf said.

Reporters converged on the apartment where Fromme had been living with another Manson disciple, Sandy Good, who warned of a group called the International People’s Court of Retribution, which would, she said, bring death to corporate leaders and politicians.

“A wave of assassins, thousands of people, will be moving through bedrooms with butcher knives,” she said. “Those people who are killing our earth deserve to die.”

Investigators found no evidence of a broader conspiracy to kill Ford, and no proof that the incarcerated Manson had given the order.

Still, Stephen Kay, a former Manson prosecutor, has long suspected Manson put her up to it as a way to win further notoriety, maybe passing word to her through an intermediary.

“There’s no way that Squeaky thought that up for herself,” he told The Times, describing her as a “space cadet.”

“Manson loved to be in the news himself or have the family in the news,” he added.

Raised in an upper-middle-class home in Redondo Beach, the daughter of an aeronautical engineer, Fromme was kicked out of her house as a teenager and met Manson on Venice Beach in 1967. He called himself “the Gardener,” the caretaker of lost flower children. Of the forces that influenced her, Fromme wrote in her memoir “Reflexion,” “Charlie and LSD stand out.”

In “Helter Skelter,” his account of the Manson murders, prosecutor Vincent Bugliosi wrote that Fromme wore a perpetual smile, possessed a “little-girl quality” and seemed to radiate an “inner contentment” that reminded him of a religious fanatic. “Charlie is love” was her doctrine. At the Spahn Ranch near Chatsworth, Manson assigned Fromme to take care of the blind, elderly owner, who was allowing the Manson clan to stay on his property, and by Bugliosi’s account, enjoyed the sexual attentions of the female disciples.

The family leader in Manson’s absence, she helped embroider an elaborate ceremonial vest for him, weaving in her own red locks. In the 1973 documentary “Manson,” Fromme posed with rifles and daggers, declared that Manson was God, and said she was ready to die for him.

“Anybody can kill anyone,” she said.

Manson did not command Fromme to accompany the band of killers responsible for the Tate-LaBianca murders in August 1969, but during their trial, she kept vigil outside the Hall of Justice in downtown Los Angeles and carved an X in her forehead in solidarity.

“After court, I was on my way to the parking lot and Squeaky and Sandy snuck up behind me, and they said they were going to do to my house what was done at the Tate house,” said Kay, the former prosecutor. “And we all know what was done at the Tate house.”

If you have information on old crimes, famous, once-famous or obscure, contact [email protected]

When Fromme was arraigned on a charge of attempting to kill Ford, she demanded the federal judge put a halt to logging.

“The important part is the redwood trees,” Fromme said. “We want to save them. Do you understand this is like cutting down your own arms and legs?” She added, “The gun is pointed, and whether it goes off is up to you all.”

At trial, she asked that Manson be brought to court to testify. The judge refused. At one point, she threw an apple at a prosecutor. In an effort to show that she never meant to fire the .45, the defense established that she had taken shooting lessons at a firing range and knew her way around firearms.

“The government was very concerned about the possibility of an assault conviction instead of an attempted murder conviction, because there was evidence she was very familiar with guns,” said journalist Jess Bravin, author of “Squeaky: The Life and Times of Lynette Alice Fromme.”

She was found guilty of trying to kill Ford and received a life sentence. In 1987, after hearing a rumor that Manson was dying of cancer, she slipped away from a minimum-security federal prison in West Virginia with the hope, she said, of being near him. She was captured two miles away. She was paroled, at age 60, in 2009.

Bravin said that when he interviewed Fromme, who maintained a kind of religious devotion to Manson until his death, she told him she had gone to the park that day uncertain about what she would do.

“She had no personal feelings about [Ford] one way or another,” Bravin said. “She was very angry at the system and what she felt was the environmental degradation. Ford was coming to speak to businessmen in Sacramento. She felt he was destroying the redwoods.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.