Before a Palmdale baby vanished, there were multiple abuse allegations. Why didn’t agencies intervene?

- Share via

Roselani Gaoa was accused of child abuse three times while pregnant with her youngest son, Baki Dewees.

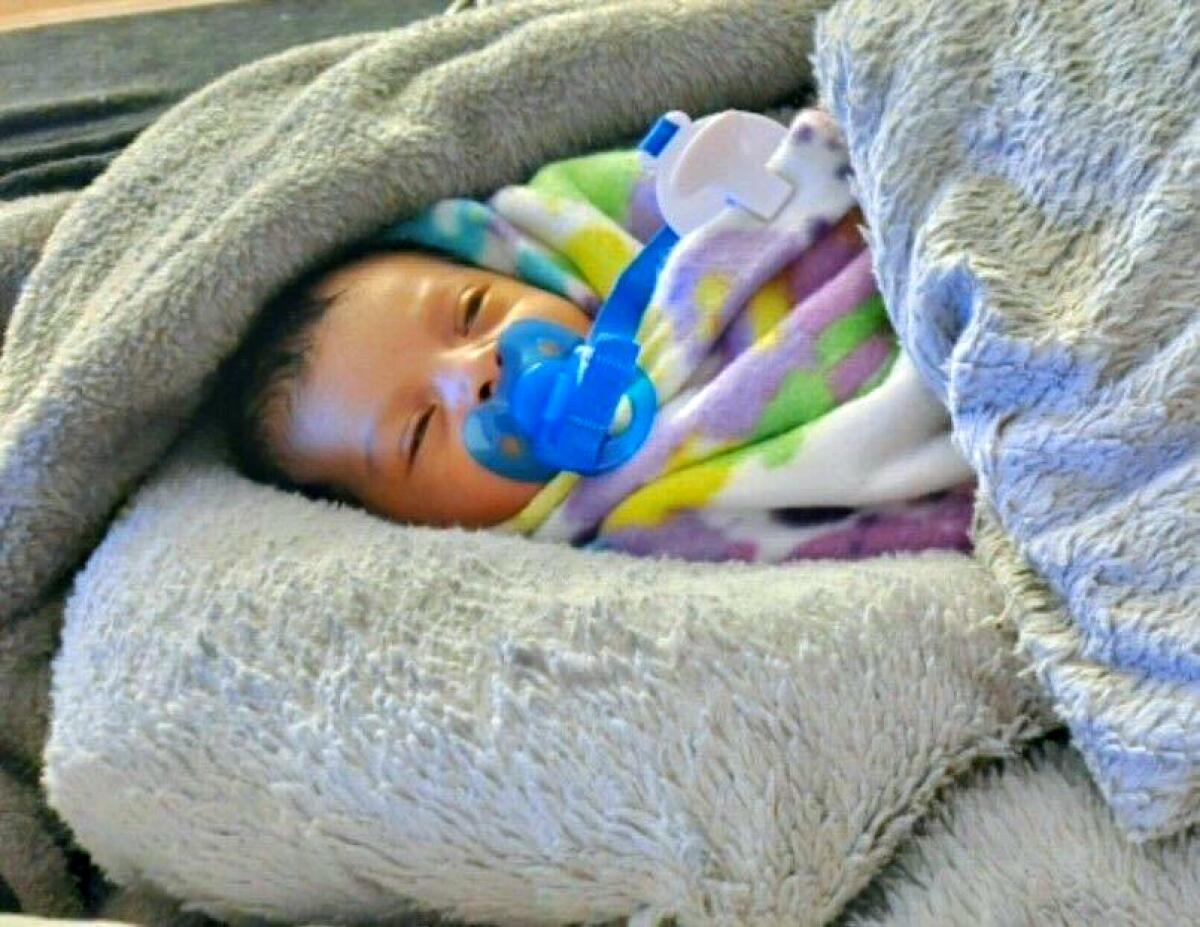

The boy was born on April 14. Less than three weeks later, he was missing and presumed dead.

An investigation into the baby’s disappearance led L.A. County sheriff’s officials to search an Antelope Valley landfill last month. His father, Yusef Ibn Dewees, was charged Wednesday with murder and child abuse, according to court records. Gaoa is jailed in Utah on suspicion of aggravated child abuse.

A Times review of court documents and confidential police records shows a history of abuse allegations in the six months before Baki’s birth and presumed death, raising questions about whether child welfare officials missed chances to intervene and save the boy’s life.

The head of the Weber County public defender’s office in Utah, which is representing Gaoa and Dewees, declined to comment.

L.A. County prosecutors are now seeking to extradite Dewees, but it is not clear when he will next appear in court.

Authorities in Utah say Gaoa was caught on video pummeling her 5-year-old daughter inside a homeless shelter a day prior to Baki’s birth. Gaoa had left California weeks earlier, not long after finding out she was facing child abuse charges in Los Angeles after she “lost control” while disciplining her 1-year-old son, according to records reviewed by The Times.

Between November 2023 and April 2024, allegations surfaced that Gaoa, a mother of four, had battered her 1-year-old son, ripped and cut another child’s hair in Los Angeles, and beat and attempted to smother her 5-year-old daughter, according to police and child abuse reports obtained by The Times and a public criminal complaint filed in Utah.

The abuse allegations brought panicked outcries from relatives and a criminal filing against Gaoa, but child welfare officials took almost no action against the parents in the six months leading up to Baki’s disappearance, the reports show. After each incident, the children were left in the custody of either Gaoa or Dewees, who was also accused of child abuse last year, according to the reports.

The Times reviewed police reports and interviewed Baki’s grandmother and law enforcement officials about steps taken by child welfare officials in the case.

The Los Angeles County Department of Children and Family Services and family welfare officials in Utah declined to answer questions for this article, citing privacy laws.

Baki’s presumed death was the latest in a series of Antelope Valley-based tragedies where L.A. County officials have been accused of failing to adequately respond to reports of child abuse. Now, some in the baby’s family are demanding answers.

“They should have done something when all this was reported. I don’t know why they didn’t do anything,” said Baki’s grandmother, Fiti Paulo. “I’m really angry with them.”

‘She refuses to seek help’

Gaoa, 25, was already struggling to handle three kids when she became pregnant again, according to Paulo.

She was “angry all the time” and frustrated by her partner, Dewees, who routinely disappeared and was frequently drunk, rarely helping with the children, according to Paulo and a report made to L.A. County DCFS in November 2023.

Neither parent was working and they were living in tight quarters with the children’s great-grandparents in San Pedro, Paulo said. The children — ages 1, 3 and 5 — were often dirty and the oldest had never been to school, Paulo said.

“I believe that she didn’t want to put them in school because the kids might say something, like what may be happening in the home, if they’re being abused, things like that,” the grandmother said.

Paulo’s frustrations boiled over late last year, when she called DCFS and said her daughter had “undiagnosed mental health issues.”

“She refuses to seek help. Mother pulled the children hair off their head and cut their hair when she was upset,” read the November 2023 Suspected Child Abuse Report, commonly referred to as a SCAR, generated from Paulo’s call to DCFS. “Father drinks every day, he becomes violent when he is drunk.”

The report alleged that Dewees punched his oldest daughter in the face, and that two of the children were bruised. But Los Angeles police officers observed “no visible injuries” on the children during a welfare check, according to an LAPD report reviewed by The Times. The officers only interviewed Gaoa, who blamed the allegations on a tumultuous relationship with her mother. They did not speak to Dewees or Paulo, according to the report.

An LAPD spokeswoman declined to comment on the case.

One month later, a doctor at UCLA Harbor Medical Center noticed bruises on the “thighs, left ear and buttocks” of Gaoa’s 1-year-old son, according to a police report. LAPD officers and a DCFS employee named Sarah Campos went to the hospital, the LAPD report said, and Gaoa admitted she “lost control” while disciplining her 1-year-old.

She acknowledged experiencing frustration with raising three children while pregnant with a fourth and asked for resources to help cope, the report said.

‘Extremely bizarre and unsettling’

Despite the second child abuse allegation against Gaoa in a one-month span, Campos “did not express any concern regarding removal of the child from the Suspect,” the LAPD report said.

Campos did not return a call seeking comment.

“Every time I called it seems like they’re not very strict,” Paulo said. “How is that not concerning?”

Sarah Font, a former child abuse investigator who is now a public policy professor at Penn State University, said the use of physical discipline against a child that young should have set off alarm bells to any investigator. Children have no capacity to learn from corporal punishment at that age, Font said, calling the response from L.A. County authorities “basically just [a] shrug.”

“I find that extremely bizarre and unsettling,” Font said, adding that Gaoa’s use of physical discipline “speaks to the idea that the mother is clearly unable to manage her frustrations.”

Font said there is no uniform standard on when to remove a child from a parent’s custody, but she believed Campos’ investigation was not thorough.

“In a case where you have clear physical injury to a young child, you want to see DCFS take steps to lessen risk,” Font said.

Not expressing concern, as the LAPD report described, “is just not doing your job,” she said.

In January, the Los Angeles city attorney’s office filed one count of misdemeanor child abuse against Gaoa. But on the day of her arraignment in March, Gaoa called the court and said she had moved to Utah. A judge rescheduled her hearing for April 5 and issued a bench warrant for her arrest after she failed to appear in court for the second time.

A city attorney’s office spokesman declined to comment on what, if any, communications city prosecutors had with DCFS.

By the time the L.A. warrant for Gaoa was issued, the family was in Ogden, Utah, roughly 40 miles outside Salt Lake City.

A third abuse allegation

Eight days after the warrant for Gaoa’s arrest, she was caught on video repeatedly punching her 5-year-old daughter in the face and striking her with a hairbrush inside a Utah homeless shelter, according to a criminal complaint.

After screaming at her daughter to “shut the f— up and go to bed,” Gaoa covered the child’s face with a blanket before “pressing down near what appeared to be where the 5-year-old’s face would be,” according to the complaint.

Gaoa gave birth to Baki the next day, and 48 hours later, she was arrested on child abuse charges, Utah officials said. She told a police officer she “knew that she had hit her daughter but didn’t mean to hit her that many times,” according to the criminal complaint.

Local authorities did not know about the prior child abuse allegations against Gaoa, according to Weber County Dist. Atty. Christopher Allred, who said the information did not appear in searches of a national criminal database. It’s not clear whether the Utah Division of Child and Family Services knew of the past allegations.

The Utah agency released all four of Gaoa’s children into Dewees’ custody on April 17, according to their grandmother and a law enforcement official involved in the case who spoke on condition of anonymity in order to discuss an ongoing investigation.

Font, the former investigator, said it is normally difficult for a child welfare agency in one state to get records of abuse in another, meaning it’s unlikely Utah officials knew of the California allegations. Font said the fact that Dewees was homeless while caring for four kids would not have been enough to revoke custody.

Dewees and the children moved in with Paulo in Palmdale, the grandmother said.

Paulo said she last saw Baki on May 3. That morning, Dewees left the home with the newborn and his 3-year-old daughter, she said. Paulo reported the boy missing on May 7, the same day Dewees returned to the homeless shelter in Ogden. There, he was asked by police about the baby’s whereabouts, according to a criminal complaint filed in Utah.

He claimed the boy was in Florida with his paternal grandparents, adopted by a California woman and then alternatively abandoned at a Los Angeles hospital, the complaint shows.

On May 9, Sheriff’s Department investigators showed up at Paulo’s Palmdale home with a search warrant. She says they handcuffed her and her husband and took custody of her grandchildren.

Dewees, the last person to be seen with the baby, had already been in custody in Utah for 48 hours at the time of the search.

“I asked them am I being arrested? They said no, so why am I being detained?” Paulo said.

Paulo said she was taken to the Sheriff’s Department’s Palmdale station, questioned for hours and kept in custody until 5 a.m. on May 10. A spokesman for the Sheriff’s Department said that Paulo agreed to be questioned and said the matter was handled properly.

By May 14, investigators were searching the Antelope Valley landfill for Baki’s remains. A law enforcement official said detectives believe Baki may have been seriously injured as early as May 2 while in his father’s custody, but he was never taken to a hospital.

Dewees was seen driving and visiting other locations around Los Angeles County with Baki on May 3. The criminal complaint made public on Wednesday indicated that Baki was probably dead by that time.

“Child abuse has no place in our society and such acts of violence are beyond the pale,” Los Angeles County Dist. Atty. George Gascón said in a statement. “Children are some of the most vulnerable in our society, and every child is entitled to safety and protection as a human right.”

The Sheriff’s Department has yet to find Baki’s remains, and officials cautioned that they may never be recovered.

Of Baki’s surviving relatives, two of the children are now in the custody of DCFS — the agency that Paulo says failed them in the first place.

Times staff writer Keri Blakinger contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.