Long Beach man started petition to ban unhosted short-term rentals in his neighborhood. It worked

- Share via

First came the all-night parties and music blaring from a neighbor’s house in Long Beach that kept Andy Oliver up at night.

Then there were the “smoke outs,” when visitors enjoying refuge from hostile cannabis laws in their home states blazed marijuana throughout the day, sending clouds of hazy smoke into Oliver’s sanctuary, his house in the city’s College Estates neighborhood.

The final straw was on Jan. 2, when a shooting victim climbed over his fence, bleeding and looking for shelter.

In each case, the source of Oliver’s grief was tourists staying in an unhosted short-term rental next door. Such rentals are listed by homeowners who are not present during the guest’s stay, as with Airbnb.

“All this happened over a year’s time, and it was beginning to be too much,” Oliver, 50, said. “This is a residential area, and something had to be done.”

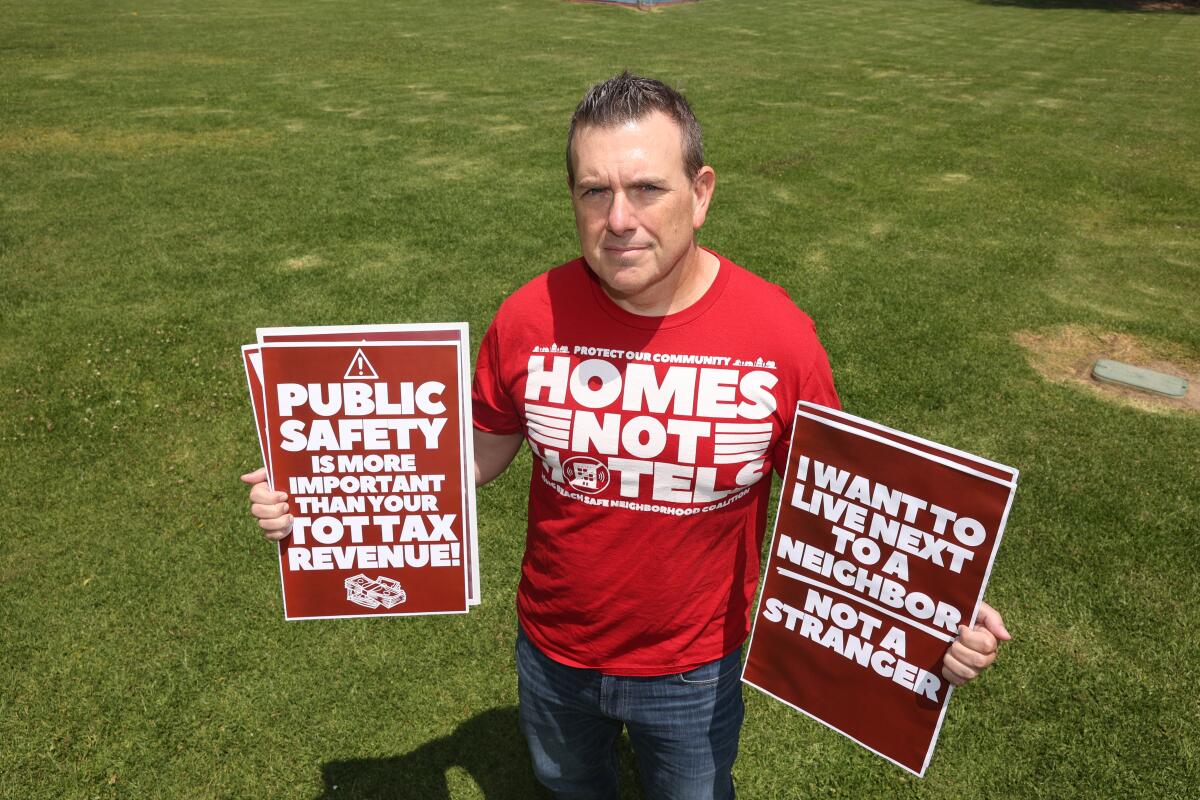

Fast-forward four months, and Oliver has successfully petitioned Long Beach’s Community Development Department to ban short-term rentals within College Estates. His win spawned nine similar petitions around the city.

“I don’t have the final count, but there are something like 755 homes, and we just got enough signatures,” Oliver said. “I heard it was close and I don’t have confirmation of the final vote, but I was informed [last week] that we succeeded.”

Oliver’s victory was the culmination of nearly a year of work, which included trying the city’s complaint hotline, speaking with a council member and, ultimately, founding an online advocacy group, the Long Beach Safe Neighborhood Coalition.

For months, coalition members commiserated on the social media site Nextdoor over their frustrations with the short-term rentals, gathering momentum for a ban.

“The common theme that we kept running into was that this was a big deal for many residents and almost all of us got the runaround from the city of Long Beach,” Oliver said. “They didn’t seem to care.”

As short-term rentals have spread, the responses across Southern California have varied.

The ordinance, five years in the making, would prohibit hosts to list second homes, accessory dwelling units or investment properties in unincorporated L.A. County.

In Palm Springs, short-term rentals were capped in specific, high-demand neighborhoods, leading to a local drop in home prices.

In Orange County, Anaheim requires a minimum stay of three nights to avoid frequent disturbances, while Seal Beach has limited short-term rentals to 31 units in the city’s coastal zone south of Westminster Boulevard.

Last year, Lakewood banned them altogether.

Similarly, Long Beach originally banned unhosted short-term rentals in the early days of the pandemic. But that ordinance was loosened to allow for 800 non-primary-residence short-term rentals, meaning people could use their second properties within the city as an Airbnb.

Currently, there are 626 non-primary short-term rentals registered in the city, according to the Community Development Department.

Jean Young, a 67-year-old technical writer, is among those with a short-term rental.

“I’m a part-time writer, and the income from rentals just smooths out the rough edges and has been wonderful,” she said.

Young splits her time between her three-bedroom, two-bathroom home in Long Beach’s affluent Bixby Knolls neighborhood and one in the sprawling senior living community at Leisure World in Seal Beach, where she spends three or four months out of the year.

She began renting out a part of her Long Beach home 11 years ago to JetBlue and Southwest flight attendants in town between shifts, then turned it into a place of refuge for traveling nurses during COVID-19. Now Young hosts physical therapists and medical residents.

Sometimes, she rents out the entire place.

“My son has since moved on to college and my mother passed away, so there’s all this room in my house to share,” she said. “It would be sad to lose that ability.”

Young said she understands the backlash from community members. The Jan. 2 shooting next to Oliver’s home on Kallin Avenue was “horrible” and an “abomination,” she said, but a citywide ban would ultimately be “damaging.”

Oliver said he initially tried other means.

He called the city’s hotline to complain about his neighbor’s rental, “but nothing was ever enforced.”

He reached out to a City Council member and the city attorney.

Eventually, he had to go grassroots.

“There were two previous petition drives that failed,” he said, “so I wasn’t sure if we would have success.”

But whenever he was discouraged, he would think back to his encounters with rowdy neighbors.

In December, he said he spoke with a bunch of 20-somethings from Texas staying at his neighbor’s house, because the “insane amount of marijuana they were smoking” was floating into his home.

“They said recreational marijuana wasn’t allowed in Texas and they were going to take advantage of their time here,” he said.

Just a few weeks later, on Jan. 2, a man standing in front of a rental in the 800 block of Kallin Avenue was shot in the lower body by an unknown gunman, according to Long Beach police.

The home had been listed on Peerspace, an online marketplace for hourly rentals, Oliver said. The shooting is still under investigation.

The victim tried to climb Oliver’s fence and smeared blood on the gate as he crossed into the yard.

“My house was closed for hours due to an investigation,” he said.

Facing a worsening housing crisis, the Hawaii Legislature overwhelmingly passed a measure that allows counties to phase out short-term rentals. Maui almost immediately announced efforts to transition vacation rental apartments into long-term housing.

As momentum for Oliver’s petition grew, help came from unexpected places.

Better Neighbors LA, a self-described coalition of hosts, tenants, housing activists, hotel workers and community members, footed Oliver’s $1,050 petition ban fee with the city.

“BNLA is happy to support neighbors like Andy in Long Beach as well as people and groups across Los Angeles County who want reasonable regulations on an out-of-control industry that affects their neighborhoods,” the group said in a statement.

Oliver said the group is also funding efforts to ban unhosted short-term rentals in nine other Long Beach communities, including El Dorado Park, Naples and South of Conant, where resident Stephen Carr is leading an effort.

Carr, a freelance photographer, said the ban was necessary after his neighbor’s home listed on Airbnb “turned into a hotel.”

He said one weekend last summer, guests in town for an electronic dance music festival stayed up every night.

“The music is blaring. There’s screaming and drunkenness spilling out into the front and back lawns till 3 a.m.,” he said. “One of the guests actually apologized the next day, but then they partied again till 4 a.m.”

Carr said he called the police, but they would only issue warnings. He also tried the city’s complaint hotline but never received a call back.

Eventually, he found Oliver on Nextdoor and linked up with Better Neighbors LA, which he said funded his $1,050 petition fee.

“There’s no regulation, no help coming from anywhere,” Carr said.

The sites that host in Long Beach such as Airbnb, Peerspace and Vrbo say they have outlets for residents to voice their concerns and point out problems.

Airbnb cited a city report in April that said the majority of its operators were “meeting compliance standards” and that there was “proactive and reactive” enforcement against violations.

Thousands of short-term rentals are breaking the law. The city is leaving millions of dollars on the table by not enforcing the rules.

The hosting site has a Community Disturbance Policy that bans parties and events that are disruptive, open-invite and draw excessive noise, visitors, trash, littering and smoking, among other issues.

Neighbors witnessing issues or violations are encouraged to reach out to Airbnb’s support staff, a company spokesperson said.

Peerspace, meanwhile, said its sites rent out venues on an hourly basis including homes, photo studios, storefronts and banquet halls. Unlike Airbnb and Vrbo, the company does not permit overnight bookings.

The company said it takes neighbor concerns seriously and asks anyone experiencing complications to reach out to its Trust and Safety team. It also said it had no listing for the home on Kallin Avenue on Jan. 2, when the shooting victim climbed into Oliver’s backyard.

Vrbo recommends that neighbors with complaints first address any issues with the host. They then suggest filling out a Stay Neighbor complaint form if a resolution can’t be found.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.