Why was 2023 such a deadly year in Los Angeles County jails? It depends on whom you ask

- Share via

It was well after dark, but Tawana Hunter lingered in the hospital parking lot, watching the minutes tick by on her phone. As midnight drew closer, she ran through all the things she wished had been different.

She wished her father had been in better health. She wished he hadn’t gotten arrested. She wished he hadn’t spent the last few months of his life in jail. And she wished that, right now, he wasn’t dying alone, handcuffed to a hospital bed.

After almost two hours of wishing and waiting, her phone rang.

“I’m sorry,” the woman began. Tawana knew what came next.

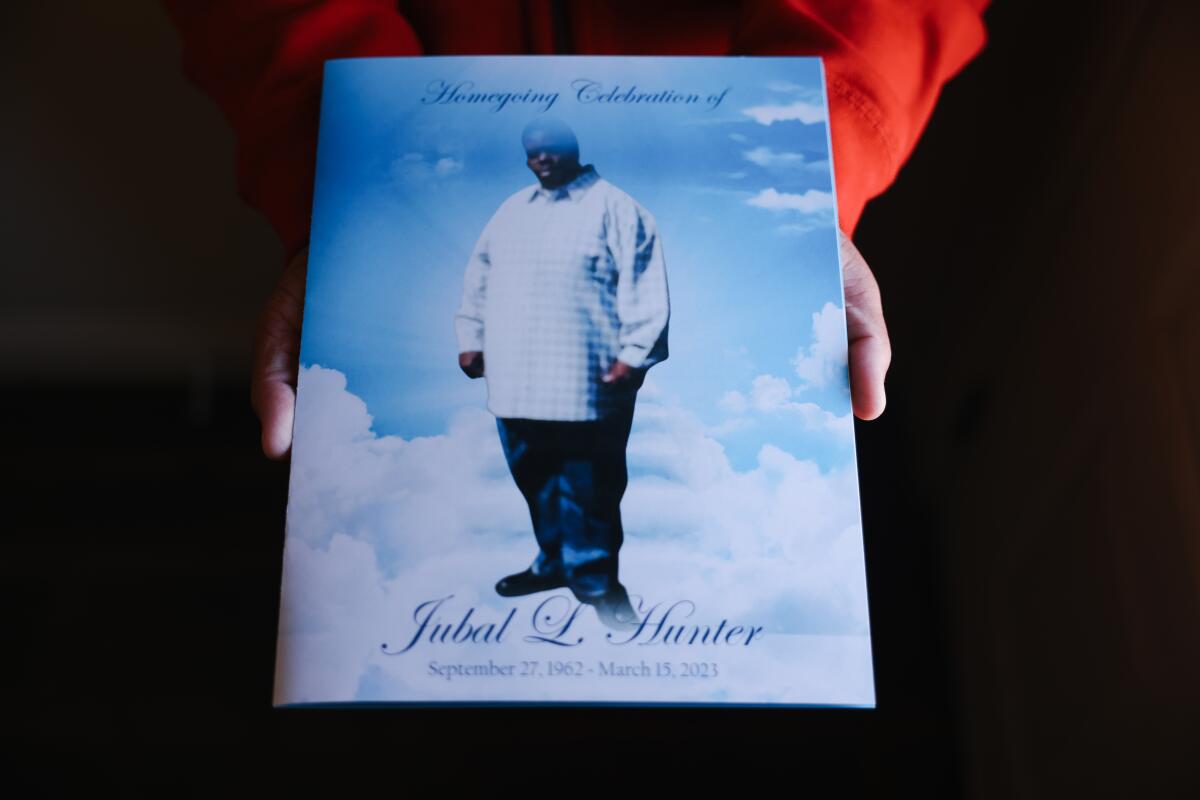

Jubal Hunter, 60, was one of 45 Los Angeles County inmates who died in custody last year, one of the deadliest years in recent history. Though the number of people in the county’s lockups is roughly a third less today than what it was a decade ago, the number of fatalities has risen so much that the annual death rate has more than doubled in that time frame. Suicides are slightly down after a sharp spike in 2021, but natural deaths are up, killings are up, and overdoses are way up compared to 10 years ago.

Yet no one seems to agree on why. Jail leaders, oversight officials and inmate advocates have cited various causes including fentanyl, COVID-19 and overcrowding. Sheriff Robert Luna, whose department runs the jails, has blamed the poor health of the inmates leading up to their arrest. Many, he told The Times, receive the “best healthcare” of their lives while incarcerated.

But a Times review of thousands of pages of autopsies, lawsuits, medical records and oversight reports found another common thread stretching across all causes of death: neglect, by both guards and medical staff.

In recent years, records show, inmates have died from jumping off railings, banging their heads against a wall and injecting drugs with makeshift needles — all in view of jail surveillance cameras that no one watched until later. At least three inmates died after stuffing paper, sanitary napkins or other items down their throats, asphyxiating before anyone intervened.

Last year, one man died after he was beaten and left bleeding for four hours before guards noticed. And last month, one man’s family filed a lawsuit alleging he was neglected for so long that his body was “cool to the touch” by the time staff found him dead from an “easily treated” medical condition.

“We think about people dying in interactions with the justice system when they’re saying, ‘I can’t breathe,’ with a knee on their neck,” said Nicholas Shapiro, a UCLA researcher who studies Los Angeles jail deaths. “But a lot of these deaths are happening in ‘I can’t breathe’ scenarios due to neglect and a lack of access to healthcare.”

Repeatedly, oversight officials have questioned the quality and frequency of required safety checks and raised concerns in quarterly reports about jailers who delay taking action when confronted with medical emergencies. Meanwhile, state authorities with the Board of State and Community Corrections cited the jails for noncompliance so many times that this year they asked the sheriff to answer questions in person about why staff fail to check on inmates at least hourly.

In a statement to The Times this week, the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department said all deaths are “tragic” but did not offer comment on individual cases.

“The Department takes every in-custody death seriously and strives to make every effort possible to prevent similar deaths in the future,” the statement said.

Similarly, the county agency that oversees jail healthcare said in a statement that it cannot comment on individual cases due to medical privacy laws.

“The Los Angeles County Department of Health Services is proud to provide high-quality, patient-centered care to all L.A. County residents, including inmates who receive care through Correctional Health Services,” the statement said, adding that the Sheriff’s Department is “ultimately responsible for escorting incarcerated persons in custody to the on-site medical clinic for care and treatment.”

When Tawana found out her father was in jail, at first she didn’t believe it, she told The Times. Though he’d done some prison time in his younger years, the man she knew was a kind grandfather, not a troublemaker. He loved taking his grandchildren to the park and spoiling them with doughnuts.

Yet in September 2020, Jubal was arrested and charged with murder after prosecutors said he shot a man to death outside his South Los Angeles apartment. Jubal said he didn’t do it. And according to his attorneys, he had simply shooed away a would-be thief prowling around his broken-down car, then gone back inside. There was no camera footage of the killing, and no eyewitnesses.

But it was a serious accusation, and Jubal had prior convictions. So the court set bail at $4 million, and he had to stay in jail amid the worsening pandemic. Court records show he had thyroid problems, diabetes, kidney failure, carpal tunnel syndrome and high cholesterol. He required dialysis three times a week, and he needed a wheelchair to get around. His daughter suspected he was in such poor health he wasn’t physically able to kill anyone.

“Clearly they got the wrong dude,” she remembered thinking, assuming that someone would soon figure out the mistake and let her father out.

Instead, he sat in Men’s Central Jail for more than two years, waiting for his chance at trial.

No one knows how many people die in jails and prisons across the country each year, so it’s difficult to say how the problem in Los Angeles compares to other places. But over the past few years, the deteriorating conditions and rising death tolls in lockups from New York to Texas to California have attracted increasing scrutiny.

A decade ago, there were more than 18,600 inmates in the Los Angeles County jails, but by the end of last year that figure had fallen to under 12,200, according to county data. Over the same span, state data shows the death toll rose from 28 in 2014 to at least 50 in 2021 before falling to 45 last year.

Despite the lack of consensus on the cause of that uptick, there are some clear trends. A Times analysis of records from the California Department of Justice shows that natural deaths in Los Angeles jails have gone up 40% since 2014, while the number of unnatural deaths — a category that includes homicides, suicides and overdoses — rose by at least 65%.

Last month, a government watchdog report noted a similar shift in federal prisons, where unnatural deaths went up by roughly 50% from 2014 to 2021. And, as in Los Angeles, the report found that skipped welfare checks, slow responses and other negligence were some of the factors that may have contributed to that increase.

As Jay D. Aronson and Dr. Roger A. Mitchell explore in their recent book ‘Death in Custody,’ that lack of data is a national problem.

In Los Angeles County, those lapses are readily apparent in the rising number of overdoses. Last year, Sheriff’s Department officials said that out of 45 jail inmate deaths, 12 were drug-related — more than twice as many as a decade earlier when the jail population was much larger.

In one case, a 35-year-old man overdosed on a jail bus in September, according to a quarterly oversight report. Staff waited 15 minutes to pull over and render aid, and the man died later at a hospital.

Three months later, another quarterly report showed that jailers at North County Correctional Facility in Castaic skipped several required safety checks before discovering an inmate who had overdosed. As in several other cases The Times reviewed, jailers only learned of the medical emergency after other inmates summoned them for help.

When a 29-year-old collapsed at North County Correctional Facility in 2022, other inmates were the first to respond, administering an overdose-reversing drug the Sheriff’s Department now keeps mounted on the jail walls. It was only after the man died that officials discovered that jail surveillance footage had captured him loading a makeshift syringe at his bunk and asking another inmate to help him inject it into his neck, according to autopsy records. Deputies later reported seeing him inject drugs on camera a few weeks before his death.

Some of the same problems showed up in a Times review of jail suicides, which spiked in 2021 when 11 people killed themselves. That May, one man with a history of trying to kill himself banged his head against a wall 60 times, according to an autopsy report. No one intervened and he later died of blunt force trauma — at which point officials reviewed camera footage and realized what had happened.

A few months earlier, autopsy records show, a man with a history of suicide attempts tried to kill himself by removing his tracheostomy tube and stuffing Q-Tips into his airway. After his cellmates alerted the guards, he was taken to the hospital — but quickly sent back to Men’s Central Jail where, the following day, he tried to remove the tube again. As jailers walked him to get medical help, he collapsed. The paramedics who tried to save him realized that he had again stuffed a Q-Tip into the breathing device.

Since then, autopsy records and oversight reports show that at least two other prisoners have died after stuffing materials — in one case paper and in one case a maxi pad — down their throats before staff intervened.

Of the dozens of cases The Times reviewed from the past three years, several involved inmates who were held in isolation despite warning signs, including histories of mental illness and recent suicide attempts. In at least one case, records showed jailers couldn’t pinpoint exactly when the prisoner was last known to be alive.

Typically, homicides are the least common type of unnatural death in Los Angeles County jails, but in recent years they’ve been on the rise. Last year, there were four inmate-on-inmate killings. In one case, an oversight report noted that the victim and his suspected killer had been housed together improperly, even though the jail’s cellmate matching system indicated that the two were “not a compatible match.”

Masoud Rahmati’s death after an apparent pre-dawn beating has renewed concerns about supervision in L.A. County jails, which have seen at least three homicides this year.

In another 2023 case, a 50-year-old mentally ill man was beaten in the shower at Men’s Central Jail and left on the floor for two hours. Other inmates moved him to his bunk where he lay bleeding for another two hours before jail staff noticed.

This year, county Inspector General Max Huntsman pointed to the failure to monitor jail surveillance cameras as an ongoing problem.

“People died recently,” he told the L.A. County Board of Supervisors in January, “while in full view of video cameras, in which there could have been an intervention, and there wasn’t, because nobody was watching.”

The Sheriff’s Department did not offer comment on that characterization but said it has a “more complicated” inmate population than in the past. In 2017, officials said, 27% of the jail population had mental health problems. Now, that figure is 42%.

Without providing evidence, the department also said there are more inmates with medical problems and addiction issues than there used to be — though, in the past, attorneys and inmate advocates have questioned those assertions.

When Jubal’s case finally went to trial early last year, his lawyers tried to tell the jury he didn’t kill anyone.

“We believed he was factually innocent of this crime,” public defender Brooke Longuevan told The Times.

But the efforts to prove that moved along slowly, in part because Jubal needed to go to dialysis three times a week. Sometimes, the proceedings got derailed by his lawyers’ concerns about his care and the conditions at the jail. He didn’t seem to have enough warm clothes, and, on the first day of trial, Longuevan said, Jubal showed up in a makeshift hat that other inmates had knitted out of a sock.

After that, jail staff sent him to court without his medically approved meals so frequently that eventually his lawyers got the judge to sign an order requiring them to give him meals he could eat.

One day, two weeks into the trial, he didn’t show up for court at all — and that was how his lawyers said they learned he was in the hospital.

“We went to the hospital to see if we could see him,” Longuevan said. “And we got there and the sheriffs told us we couldn’t — even though we had a court order.”

For days, the deputies refused to let Jubal’s lawyers in, Longuevan wrote in court filings. At one point, she said, deputies claimed attorneys for the county told them not to let the lawyers see him — though the county attorneys denied that when Longuevan contacted them the next day. So Jubal’s lawyers returned to the hospital, where Longuevan said a lieutenant threatened to arrest them if they didn’t leave.

Eventually, they found out Jubal had COVID-19 and was receiving oxygen. And as the days ticked by, the legal team grew increasingly worried, both about his health and about the possibility that the delays would lead to a mistrial, forcing them to start all over again in court.

But by early February his condition had improved enough that he was cleared for discharge — if the Sheriff’s Department would agree to pick him up.

“Our understanding from LASD jail staff is that they are declining to transport Mr. Hunter back to the jail because of his oxygen requirements,” Longuevan wrote in a worried email to the jail medical director.

The medical director replied three days later, saying he’d look into it. By the following day, Jubal was back in the jail, and able to call his daughter again.

“I still feel short of breath,” she remembered him saying, as she listened to him struggle for air and wondered why he’d been sent back to the jail. She thought he was supposed to be released with oxygen, and he didn’t seem to have it.

“They released me,” he continued, “but I’m not OK.”

Though unnatural deaths have risen sharply, natural deaths — those caused by disease and illness — still account for roughly half of the yearly fatalities in L.A. County jails. And while research shows that inmates are disproportionately likely to have certain chronic health problems before ending up in custody, inadequate care behind bars can cause those problems to become deadly.

Last winter, the jails came under fire for failing to provide enough warm clothing when two inmates died after showing signs of hypothermia. One, a 61-year-old man housed at Twin Towers jail, had a body temperature of 87.6 degrees by the time he arrived at the hospital. He died three weeks later of multiple organ failure, records show.

In June, when deputies found a 55-year-old man unresponsive in his cell at Men’s Central Jail, the medical examiner chalked his death up to a “history of heart failure.” According to oversight reports, his family had been telling jail officials for months that he needed more medical care and that he seemed to be deteriorating. By the time he died, he’d lost roughly 100 pounds — and neither the Sheriff’s Department nor jail healthcare providers had noticed or intervened.

His case was one of several in which records show that inmates and their families warned officials of serious symptoms — such as vomiting, diarrhea and pain — that went untreated for days or weeks before their deaths. In a lawsuit filed last year, one female inmate’s family alleged the woman died from untreated alcohol withdrawal days after she was arrested on suspicion of shoplifting. Her death was considered accidental.

When 32-year-old Travis Freeman was booked into jail last May, he had a number of medical problems, including hepatitis, fentanyl addiction, alcohol dependence and bipolar disorder. Though the jail treated some of these problems, according to a lawsuit filed last month, staff “completely ignored” his stomach ulcers. At one point, he went to urgent care because he was throwing up — but he was soon sent back in a cell at Men’s Central Jail.

A few days later, his cellmates started calling for help when they noticed he’d fallen unconscious. By the time staff arrived, the lawsuit said, Freeman was “pulseless, not breathing, pale, and cool to the touch.” He was declared dead at the jail, and the medical examiner later noted that his gastrointestinal tract was filled with blood caused by duodenal ulcers.

“Such a condition is easily treated, produces symptoms over an extended period of time, and does not cause sudden death,” the lawsuit said. “Both the medical and custody staff were deliberately indifferent to Mr. Freeman’s medical needs in that they ignored his obvious suffering, symptoms and need for help, and failed to summon emergency medical care in a timely manner.”

The suit also described other delayed responses in recent years, including one case in which a woman died after jailers didn’t act immediately when they discovered her unresponsive and covered in feces. Neither the Sheriff’s Department nor the Health Department offered comment on the lawsuit or the cases it mentions.

At a recent meeting of the Board of Supervisors, one of the jail’s top doctors said part of the problem is that there aren’t enough jailers to bring inmates to their medical visits.

“I don’t have the people to get my patients to me,” Dr. Tim Belavich told supervisors in January. “There aren’t enough workers to get the patients to the appointments so they can be seen, and seen timely.”

Two weeks after Jubal got out of the hospital, his trial ended.

“It was a hung jury,” Longuevan said. “But he wasn’t there for it.”

Hours earlier, on the evening of Feb. 21, 2023, he’d been rushed back to the hospital with respiratory failure. Over the next few weeks, medical records show, he nearly died at least twice, tested positive for COVID-19, went into septic shock and was eventually intubated.

Then on March 10, Tawana said, the hospital called and asked her to come in and talk about taking her father off life support. His lawyers tried to get the court to grant a compassionate release so his family could visit him more freely in his final days — but Longuevan said they couldn’t get the hospital to give them the paperwork they needed in time.

In the end, the jail and the hospital agreed to let Jubal’s family come see him for a couple of hours on the evening of March 15. His relatives gathered at the Los Angeles General Medical Center and waited more than an hour for someone to let them in. By the time medical staff extubated him, only 20 minutes remained in the scheduled visit.

When they left, Jubal was barely breathing. He looked frail and pallid — a shadow of the man Tawana knew.

She assumed it wouldn’t be long, so she stayed nearby to wait. When the call finally came, Tawana remembers asking the hospital representative if she could come in to see her father’s body.

At first, the woman said she wasn’t sure. More than an hour later, Tawana said, the hospital called back with an answer.

No. The jail wouldn’t allow it.

Troubling deaths in the Los Angeles County jails are not a new phenomenon. In a study published last year, Shapiro and his fellow researcher, UCLA professor Terence Keel, detailed a case in 2016 in which a 33-year-old died of dehydration and another in 2010 in which a teenager starved to death.

The study, which analyzed 58 autopsies, also found that “medical neglect and incompetence” were key drivers of natural deaths in the Los Angeles jails. But understanding factors that might contribute to jail deaths still doesn’t explain why those deaths kept rising.

“I’m baffled,” said Melissa Camacho, a senior staff attorney with the American Civil Liberties Union of Southern California. “I don’t have any reason to believe that deputies or medical staff are any more neglectful in recent years than in the past, and I don’t have any reason to believe that people are entering in the jails in a different state of health than in years past. To me it’s a sign that the county has not taken an all-hands-on-deck approach.”

State and county data show that the pandemic and the fentanyl crisis account for some of the increase. But if the jail death rate stayed where it was a decade ago, a Times analysis found, there would have been fewer than 20 deaths last year. Instead, there were more than 40 — a far larger jump than either overdoses or COVID-19 would explain.

“I have resigned myself to not figuring that out,” Shapiro said. “There are so many forces that ebb and flow, and they have coalesced in a way that resulted in a lot of deaths. Maybe they will reduce over the next year — but that doesn’t mean we’ve improved anything.”

In a December interview with The Times, Luna was similarly perplexed.

“Every time I see a notification that somebody dies in our custody, it’s like, ‘What the heck?’ You don’t want to see any,” he said. “I don’t want anything to go wrong while they’re in our custody.”

In recent months, the sheriff and others have offered solutions: buying newer body scanners to search inmates for drugs, building a new facility with more space for treatment and hiring more staff. And so far, data show that 2024 is on track to be less deadly than 2023.

Such progress brings little comfort to the Hunter family.

Early last spring, a judge finally dismissed the case against Jubal. It was not because he was innocent but because, by that point, he was dead.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.