The fight to move the Catholic Church in America to the right — and the little-known O.C. lawyer behind it

- Share via

Two very different versions of Catholicism played out on a Tuesday in October.

In Rome, Pope Francis presided over an unprecedented synod on modernizing the church, inviting not only clergy, but lay people from around the world to discuss issues such as the ordination of women, ministry to gay and transgender people, empowerment of Indigenous communities and the rights of the poor.

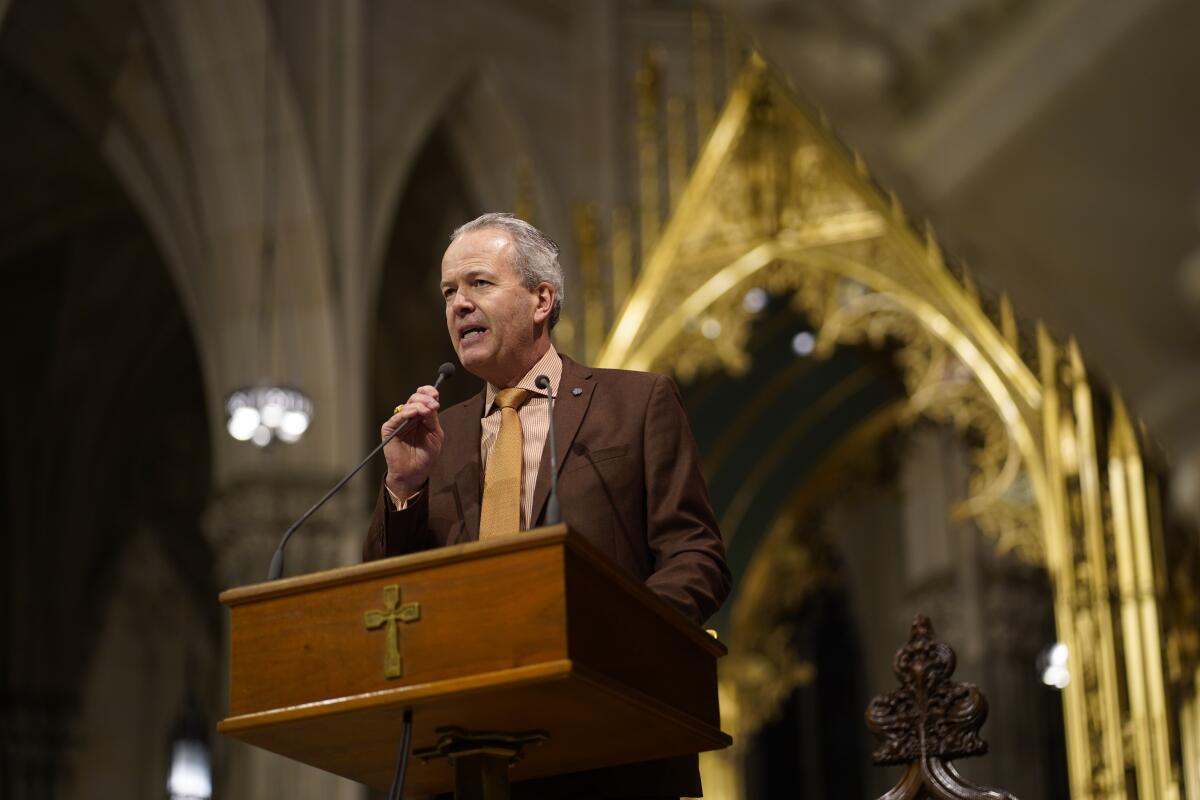

In New York, meanwhile, a Catholic millionaire from Orange County led an event that seemed a throwback to the church of the 1950s: Priests in ornate vestments marched down Broadway with a police escort, the Eucharist held aloft under a gilded canopy and accompanied by wafting incense, candle bearers and nuns in habits and waist-length veils.

“We can retake the culture of America,” declared Tim Busch, an Irvine lawyer and hotelier who organized the procession as part of a Catholic conference aimed at wealthy businesspeople. The gathering’s message, as Busch later summarized it, was that “woke ideology won’t last.”

At the Vatican, a respectful dialogue about reforming the church; in the U.S., a high-profile display of old-school church power.

Among rank-and-file American Catholics, Francis is enormously popular as he enters the second decade of his papacy, with 84% of weekly Massgoers holding a favorable opinion of him. But as he nudges the global church left, an elite group of U.S. conservatives led by Busch is trying to pull the American church right.

From an office a few blocks from John Wayne Airport, Busch, 69, has helped steer this small but powerful faction of Trump-aligned Republicans through a nonprofit he created, the Napa Institute, to rally conservative Catholics. They distrust Francis’ approach to LGBTQ+ people and the divorced, and bristle at how he has framed liberal priorities like climate change and economic inequality as “pro-life” issues on the level of abortion.

Nowhere is the chasm clearer than in the metaphors each side chooses. Francis talks of a “field hospital” church venturing into the world “concerned more with those who suffer than with defending its own interest.” Busch has described the Napa Institute as building a Catholic fortress in an increasingly godless America where the faithful “hunker down and survive” until secular society self-destructs.

Busch’s rise — the progressive National Catholic Reporter calls him “easily among the most influential laymen in the U.S. and Rome” — reflects the diminished power of American bishops from the clergy sex abuse scandals and the particular way Catholics have featured in today’s divided politics, especially when it comes to abortion.

Busch and other church conservatives are outraged that fellow Catholics Joe Biden and Nancy Pelosi are full-throated supporters of abortion rights and view them as almost diabolical betrayers of the faith. Busch himself has said both are “masquerading as Catholics” and that the president is “inspired by evil.”

Catholics connected to Busch proved instrumental in Republican rollbacks of abortion access. Donald Trump delegated the vetting of Supreme Court appointees to Leonard Leo, the Federalist Society co-chair who sits on the board of an organization that funds Napa Institute programs and whom Busch has publicly lauded as a daily-Mass-attending Catholic. Two justices recommended by Leo were devout Catholics and the third was raised in the faith. All voted to overturn Roe vs. Wade.

Trump, who is not religious, at times seems to revel in the divisions within the church, telling a New Hampshire rally this year, “How would a Catholic ever vote for Joe Biden?”

Busch has not criticized Francis publicly, but he has used his wealth and connections to elevate the pope’s detractors. His institute has bestowed honors and plum speaking slots on clergy who question Francis’ fitness and motives.

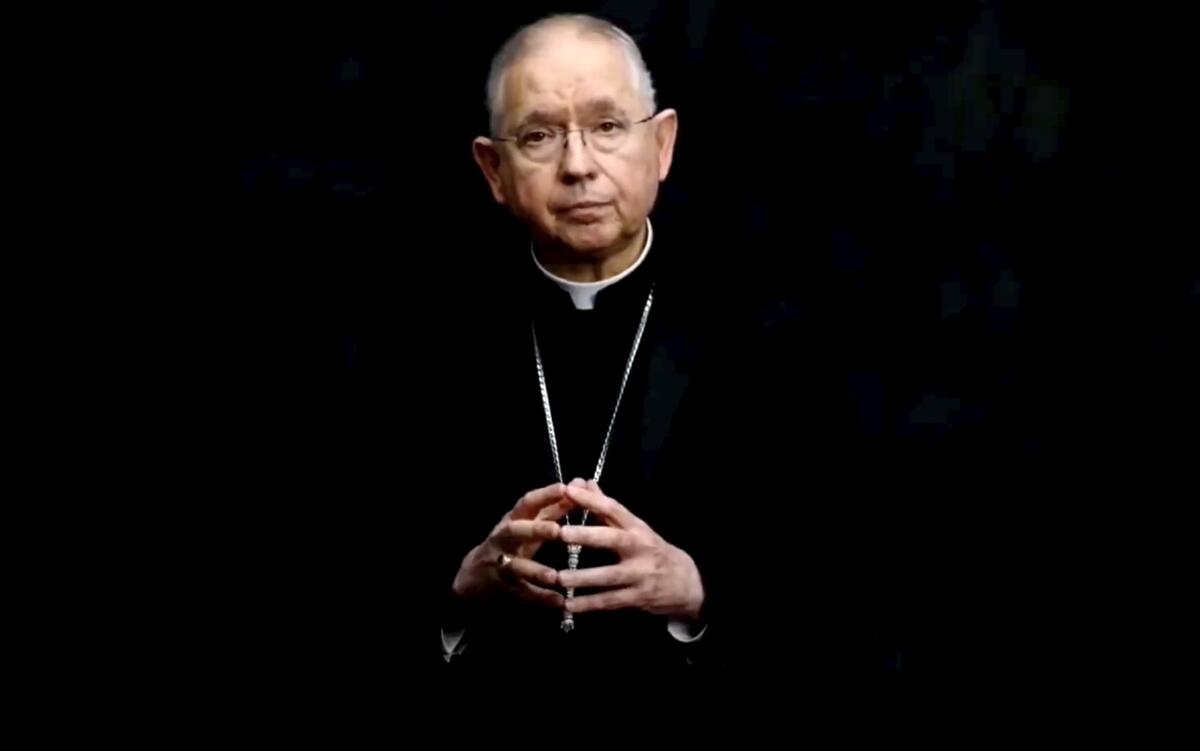

Busch invited Cardinal Raymond Burke, who has decried “pervasive confusion and error” in Francis’ tenure, to deliver a keynote address in 2019, and gave Texas Bishop Joseph Strickland, a vaccine skeptic who blessed a rally of election deniers, an award for “defense of moral truth” in 2020. In November, following years of digs at the pope, the Vatican stripped Burke of his Vatican apartment and salary and booted Strickland from his post.

Though few of the nation’s 61 million Roman Catholics know about Busch or the Napa Institute, he and his allies have drawn the attention of the pope, who noted this year the U.S. church’s “very strong reactionary attitude.”

“Those American groups you talk about, so closed, are isolating themselves. Instead of living by doctrine, by the true doctrine that always develops and bears fruit, they live by ideologies,” Francis said in August when asked by a fellow Jesuit about the lack of respect shown to him in certain parts of the U.S.

Francis did not specify the groups undermining him, but Austen Ivereigh, a British journalist who has written two biographies of Francis and collaborated with him on a third book, said the pope has a firm grasp on those he sees as arrayed against him: “He would certainly have thought of institutes like Napa. Absolutely.”

Busch declined interview requests. In an emailed response, he wrote that he and his affiliates “universally recognize Pope Francis as the Vicar of Christ, pray for him, and understand the obedience that is owed to the Holy Father, regardless of whatever spirited and respectful dialogue and debate there might be regarding the contours of our faith and morals.”

Busch’s influence stretches across Catholic America from its largest archdiocese, Los Angeles — he calls Archbishop José Gomez “one of my closest advisors” — to South Bend, Ind., where his institute has funded lectures at the University of Notre Dame by conservatives like Justice Clarence Thomas, to Washington, D.C.

The institute has an office in the nation’s capital, and Busch is also a key player at Catholic University there. In 2016, his family gave $15 million, the largest donation in university history, to fund what is now known as the Busch School of Business.

Those who know Busch said he is motivated by a sincere and deep faith, and at times it has led him to break from the expected conservative path. In 2017, as the Trump administration began separating migrant families at the southern border, Busch invited Gomez to speak in defense of immigrants to a symposium of Catholic conservatives in D.C.

When contacted by The Times for this story, friends said Busch had recently developed his own worries about divisions in the church and was quietly working to address the discord that some blame at least partially on him.

Earlier this year, he initiated a meeting with the progressive American priest Father James Martin, an advisor to Francis reviled in right-wing circles for his advocacy for gay Catholics. And, they said, Busch this fall began inviting people of diverse political viewpoints to monthly dinners.

“Tim hates the polarization,” said Father Roger Landry, the Catholic chaplain at Columbia University. “Tim wants to fix the polarization.”

Busch grew up one of six children in Clinton, Mich., about an hour outside of Detroit. His father had a small supermarket chain, where he began working at age 7. He started attending daily Mass in the fourth grade and contemplated being a priest, he has said. Instead he got a law degree at Wayne State University.

He headed west to Orange County, which in the 1980s, he has said, was “on fire, expanding.”

Busch admits that he has never taken a single course in theology or philosophy. His road to influence in the church came through money and willingness to go around bishops to get things done.

In the early 1990s he and his wife, Steph, were searching for an elementary school for their two children convenient to their home in the affluent Laguna Hills’ Nellie Gail Ranch. Steph Busch, a Protestant who converted to Catholicism when her children were young, was shocked, Busch has said, by the “rundown facilities” of the diocesan schools.

“Like sending my kids to a prison,” Busch recalled in a 2014 interview.

Busch was doing well financially with a successful estate-planning practice serving high net worth individuals, as well as an ownership stake in the family supermarkets. But rather than handing a check to the diocese to upgrade the existing schools, he and other people of means built a new Catholic school independent of church control.

“We were very strict about answering to [the bishop] about the Catholic issues, but we were able to hire a little differently. Money was less of an object,” recalled Marc Spizziri, an owner of car dealerships who co-founded St. Anne in Laguna Niguel with Busch.

As their children grew, Busch and other parents returned to the same model to open JSerra High in 2003 in San Juan Capistrano. Both schools remain sought after for South Orange County families at a time when some Catholic schools struggle. JSerra, a sports powerhouse with an impressive 37-acre campus, attracted 800 applicants for 375 seats in its freshman class this year.

Busch’s success in O.C. came at a dreary time for the church. The sex abuse scandals had cost bishops and clergy the respect of the community, and the attendant payouts to victims made for ruinous balance sheets. Yet here was a layman using his own money to open shiny new schools that quickly filled with a new generation of Catholics, albeit largely rich ones.

“Having wealth does not insulate you from problems like divorce, substance abuse, loneliness, a culture saturated in sex,” Busch told the Wall Street Journal in a 2010 column lauding his efforts. “These kids need the Catholic message as well as anyone.”

He had particular sway in the Orange diocese. When then-Bishop Tod Brown wanted to build a costly new cathedral during the 2008 economic downturn, Busch stepped in and negotiated for the comparatively cheaper purchase of the Crystal Cathedral, televangelist Robert Schuller’s Garden Grove church complex.

“This is the way to go. We should be buying this,” Busch insisted to a “timid” Brown, according to an account he gave in 2021. He recalled, “Some of the priests wanted it. Some of the priests didn’t. And frankly they were trying to kill the deal using passive aggressive approaches. But we just kept pushing forward.”

The acquisition of Christ Cathedral, as it is now known, for $57 million is regarded by many as a triumph, providing a vast, architecturally stunning campus in a prime location for a fraction of the cost of new construction.

Busch carried the lessons in Orange County about maneuvering around or even through the hierarchy as his national profile grew. In a particularly bold remark in 2018, he told a conference about the importance of lay leadership that he respected priests and bishops “to the extent they are compliant with the normal business acumen and behavior.”

This is the post-scandal reality for American hierarchy, said Tom Roberts, former National Catholic Reporter editor.

“Given … their real loss of credibility as a voice and a force in the culture … there’s a huge vacuum,” said Roberts, who has criticized the influence of wealthy conservative lay people. “People like Busch are essentially building structures that are alternatives to the U.S. bishops’ conference in terms of communications and defining the narrative for Catholics in the wider culture.”

The most direct attack on Pope Francis by American conservatives came in 2018 — with Busch playing a key role.

An archbishop who had served as Pope Benedict’s diplomatic representative in the U.S., Carlo Maria Viganò, released a scathing 11-page letter demanding Francis resign. The letter accused him of conspiring to protect disgraced American Cardinal Theodore McCarrick, who had been accused of sexual abuse of seminarians and others.

“How many other evil pastors is Francis still continuing to prop up in their active destruction of the Church!” Viganò wrote. (McCarrick was charged with sex crimes in two states, but deemed incompetent to stand trial.)

Later key parts of what Viganò alleged were proved false or unrelated to the current pope. The archbishop went on to make increasingly bizarre statements that led even conservatives to label him an unreliable conspiracy theorist.

But for a period of time, the letter represented a serious attack on Francis’ papacy. The release of the letter seemed timed for maximum damage to the pope. It was disseminated by a newspaper owned by the Eternal Word Television Network (ETWN), a Catholic media outfit on whose board Busch served, as Francis departed a successful trip to Ireland, where he had met with sex abuse victims. And Busch was quick to step forward to support the claims against the pope.

“Archbishop Viganò has done us a great service,” Busch said in a front-page New York Times article. “He decided to come forward because if he didn’t, he realized he would be perpetuating the cover-up.”

Busch told the paper that he believed that the claims were “credible” and in a later letter to supporters called Viganò “an honest man” and urged action: “It is a time to stand up, not stand down.”

Even as Viganò’s credibility unraveled, Busch continued boosting his claims, telling a conference in October 2018, “Viganò has given us an agenda .… We need to follow those leads and push that forward.”

Some conservative clergy allies of Busch also vouched for Viganò. In Texas, Strickland instructed his priests to read a statement at Masses saying he found the allegations credible.

While a handful of American bishops close to Francis issued statements of support for him, “the vast majority of bishops said nothing, which was one of the most shocking moments of my life as a scholar,” said Villanova University theology professor Massimo Faggioli, an expert on the inner workings of the church. That all the bishops didn’t jump to Francis’ defense, he said, “was a statement of how important sectors of U.S. Catholicism were .…”

One who stayed mum was L.A.’s Gomez. He serves on the EWTN board alongside Busch, who has called him “a dear friend.”

Gomez declined to comment on their relationship. He said through a spokeswoman that he frequently promotes Francis’ teachings and causes, and is “not involved in the editorial content” of EWTN as a board member.

Busch did not respond to questions about Viganò.

Francis was circumspect about the Viganò letter initially. In the years since, he and his supporters have trained their anger on EWTN.

The network “has no hesitation in continually speaking ill of the pope,” Francis said two years ago, calling EWTN attacks “the work of the devil.” In March, San Diego’s Cardinal Robert McElroy said he wouldn’t permit the network on his diocese media, saying, “The main anchors of the channel constantly minimize the abilities and theological knowledge of Francis, cite Archbishop Carlo Maria Viganò’s slander of the pope and try to move the world away from the reforms the pope is signaling.”

The network is headquartered in Alabama, but has a West Coast broadcasting center on the grounds of the Christ Cathedral in Garden Grove. A spokesperson for the Bishop Kevin Vann did not respond when asked about his decision to give a home to a network criticized by the pope.

Asked to explain his involvement with EWTN, Busch noted, “Without EWTN, many of the homebound and the elderly would be without the Mass and other opportunities for guided prayer, and Pope Francis would reach vastly fewer people in his own words.”

Busch attends Mass every day and spends at least an hour a week praying before the Eucharist, he has said, accomplishments made easier by a fully functioning chapel in a corner of his Irvine office building.

The Queen of Life chapel is outfitted with stained glass, carved wooden pews, the Stations of the Cross and arches recalling a cathedral. A priest from the Orange Diocese celebrates a daily lunchtime Mass.

On the other side of the chapel wall is Busch’s law firm and Pacific Hospitality Group, a private company with interests in upscale hotels and resorts. Busch serves as chief executive. The company has at various times operated some of California’s most luxurious and best known properties, the Bacara Resort & Spa in Santa Barbara, the Estancia La Jolla Hotel & Spa and the Balboa Bay Club in Newport Beach, among others.

At his hotels, there is no porn available on guest room televisions, but there are rosaries and crucifixes. He has installed prayer chapels in some properties, and at company Christmas parties, he leads some of his firm’s 1,700 employees in grace before the meal.

Busch customized the interiors of two Mercedes Sprinter vans as offices so he could work while being chauffeured through traffic, according to associates. The license plate of one based in Irvine reads JOHNPII while the second, in Northern California, is FRANCIS I.

Busch and his wife have lived in the same Laguna Niguel home where they raised their family since the 1980s. (They own a second home at an Indian Wells golf resort.) The house is decorated with Catholic art, including ceiling murals, and has a private chapel.

In his public appearances, Busch comes off as a wholesome, Midwestern baby boomer. He jokes about getting his grandchildren to pay attention during Mass, and revealed during a presentation for Catholic professionals in Arizona that the sins he struggles most with were drinking too much wine and impatience with family and friends.

In 2010, Busch was supposed to be enjoying a family vacation in Hawaii when, he has said, the Holy Spirit moved him to create the Napa Institute: “I picked up my dictaphone and I dictated exactly what the conference would look like.”

His vision was for a “Catholic Bohemian Grove,” a reference to the secretive annual summer gathering of powerful men in Sonoma, or a church version of the Aspen Institute. At the time, reliably conservative Benedict XVI was pope, but Busch was alarmed by the drift toward secularism in America, even among his Catholic friends.

“They, on a regular basis, don’t attend Mass on Sundays,” he marveled in 2020, noting that such an unexcused absence constituted a mortal sin. “They don’t seem to know the gravity of what they’re doing.”

The Napa Institute’s flagship event is a four-day July conference that attracts about 800 people to Busch’s Meritage Resort & Spa in Napa. Tickets run to $2,900, and the crowd of well-heeled and clergy are treated to gourmet meals, wine from Busch’s Trinitas Cellars vineyard and cigar receptions. There are also more than 130 Masses, dozens of opportunities for confession, spiritual talks and speeches by conservative theologians and stars of the political right, such as Lindsey Graham, Mike Pence and Bill Barr.

The broad themes are the wisdom of conservative Catholicism, and its corollary, what’s wrong with America today. The sources of outrage are sometimes indistinguishable from GOP talking points — from the New York Times’ “1619 Project” to hipster socialism to antifa violence.

Black Lives Matter, Busch has told Napa audiences, is “a Marxist organization against the family ... trying to overthrow the United States of America.” He has said transgenderism is “complicit with evil,” and same-sex marriage is “a lie.”

“It’s like a Catholic version of Make America Great Again,” said Francis biographer John Gehring, who is writing a book about the contemporary American church and has reported from institute events. “The liberals are at the gates, and they are fighting to hold on.”

Priorities of the pope such as economic inequality and the climate crisis get little attention at the Napa conference, he said, calling it “this strange parallel universe that does not at all fit with the kind of church Pope Francis is calling us to.”

The invited speakers and guests include clergy seen as openly hostile to Francis. The pope’s most outspoken critic, Burke, bemoaned to a Napa Institute audience in 2019 the “pervasive confusion and error in the church today.”

“I see here so many individuals and also groups and associations … who get the picture of the crisis that we’re in,” he said in a speech greeted with sustained applause.

In stripping Burke of his salary and large Vatican apartment, Francis cited the cardinal’s “disunity,” the Associated Press reported in November. (Busch told The Times that Strickland, the deposed Texas bishop, would no longer be invited to speak at Napa events given his ouster by the Vatican.)

Busch wrote in an email that every speaker at his institute “though they may at times seek to debate or dialogue about aspects of Catholic teaching” recognize Francis as “deserving of our love, obedience and prayer.”

Busch’s platforming of Francis’ opponents in the past spoke louder than any deferential words, said theologian and canon lawyer Dawn Eden Goldstein, who writes for the moderate Catholic news site Where Peter Is.

“It’s a dog whistle for their people, saying we are going to present to you the champions of the faith because the pope is not championing the faith … that you know and you love,” Goldstein said.

By any accurate yardstick, Pope Francis is no liberal.

He is emphatically opposed to abortion, even comparing it to hiring a hit man. He has referred to same-sex intimacy as sinful and refused to allow gay marriage in the church. He has not permitted women to become priests or divorced and remarried Catholics to receive Communion. He has kept the ban on contraception.

Yet he has become popular with liberals, even secular ones, for his focus on the environment and the poor and the respect and kindness he has shown marginalized groups. He has invited transgender Romans to his weekly audience and recently said trans people can serve as godparents and witnesses at weddings. He has met repeatedly with gay advocates and agreed this year it was permissible for priests to bless gay couples in some instances. (The Vatican on Monday released guidance about such blessings, saying that while they should in no way be confused with marriage rites, “the ordained minister could ask that the individuals have peace, health, a spirit of patience, dialogue, and mutual assistance — but also God’s light and strength to be able to fulfill his will completely.”)

Francis has rolled his eyes at what he sees as conservatives’ blind focus on sexual transgressions.

“We look at the so-called ‘sin of the flesh’ with a magnifying glass,” Francis said in August. “If you exploited your workers, if you lied or cheated, it didn’t matter. And instead [only] sins below the waist were relevant.”

William Doino Jr., a conservative Catholic writer who admires Francis, said that the pope “is a victim of mistaken identity” from both progressives who see him as a radical revolutionary and conservatives who view him as caving to the world.

“He’s neither. He’s sort of a transcendent figure,” said Doino. “He’s speaking from the classic Catholic position, but he’s digging more deeply into it.”

Fellow right-leaning Catholics, he said, often despise Francis because, rather than reading his writings for themselves, they allow liberals to define him in the media: “Then they react to that. They take the bait. It’s so ironic.”

Francis hosted Whoopi Goldberg, a non-Catholic, at the Vatican in October, a meeting “The View” host later said she had initiated to thank him on behalf of gay and divorced friends who felt embraced by the pope.

It was the sort of headline-grabbing scene that drives Busch allies mad. Goldberg has talked about giving herself an abortion at 14 and advocated for access to the procedures in recent years by saying, among other things, that God supported abortion because he wanted women to be free.

“It’s disconcerting to me to see people who hate the church’s teaching getting fawned over by Pope Francis,” said screenwriter Barbara Nicolosi, a former nun who served on the board of a Busch nonprofit. “People said to me, ‘Well, Jesus met with sinners.’ And I said, ‘Yes. And Jesus told them, ‘Go and sin no more.’ Jesus didn’t say, ‘Hey, you’re doing great.’”

Busch did turn to Pope Francis on one occasion when he was in a public relations predicament with potential business implications.

A Rotary group in Napa had tapped him, as a wine country hotel developer, to serve as grand marshal of the 2014 Fourth of July parade. Local LGBTQ+ activists were furious. Busch had given $10,000 to Proposition 8, the anti-gay marriage ballot initiative, and denounced same-sex relationships in an interview with a Catholic magazine as “against natural law and categorically wrong.”

“We were not going to line up behind Tim Busch. That was not going to happen,” recalled activist Deb Stallings. She and others began circulating a petition to oust him that drew notice from politicians and the media.

Busch met with activists and apologized. He said his views had evolved, revealed that one of his brothers was gay, and pledged to follow the example of recently installed Francis, who had famously said about gay people, “Who am I to judge?” He even gave Stallings a rosary he said was blessed by the new pope.

“It was enough to give me hope that he and people like him were changing,” she said. The activists relented, a detente that earned Busch positive press coverage.

In the years that followed, he continued attacking gay marriage publicly, even acknowledging that in the modern era it made him “a bigot” in the eyes of many.

The brouhaha illustrated the two worlds Busch straddled. The hospitality industry, where he made much of the money he used for his Catholic causes, embraced gay people. His hotels host LGBQT+ groups for parties and same-sex weddings, and his employees included many openly gay people.

“It felt like a non-issue,” said Ryan Giffen, a hospitality executive who consulted for Busch’s company and whose husband worked there in marketing for years.

Giffen said that when his husband won a company award, they went as a couple to a small celebratory dinner with Busch.

“He welcomed me to the table,” Giffen said. He recalled that there was “a very formalized prayer” followed by a convivial meal.

Some with significant political and religious differences with Busch said he was surprisingly open to dialogue. State Sen. Bill Dodd (D-Napa), a Catholic, said that when he left the Republican Party a decade ago, Busch stopped contributing to his campaigns, but kept donating to his charity causes and meeting him for meals.

With some encounters across the political divide, Dodd said, “you just feel like, ‘Wow if I engage in this conversation it’s not going to be good for our relationship.’ Tim, on the other hand, is not afraid to hear the other side.”

At a meeting of Catholic professionals in Oklahoma two years ago, Busch took jabs at Gov. Gavin Newsom’s handling of COVID, attacked the Biden administration — “a time of despair” — and praised Trump as “like Cyrus in the Old Testament,” the Persian king who freed the Jews from captivity in Babylon.

Then he swiftly shifted to practical spiritual advice Catholics of any background might use to deepen her faith.

Go to the same priest for confession every time for increased accountability, he told the group. Bring a notebook to Eucharistic adoration so you can record what you hear from God. Ask your guardian angel for help before tough work meetings.

In the next sentence, he made a dizzying pivot back to GOP talking points.

“I realize that storming the Capitol, all this kind of stuff, is in the news today, but there’s going to be history books written about Trump and the turning point he created in our democracy,” he said.

Supporters say Busch’s staunch opposition to abortion is key to his political views. He has boasted about the influence of Leo, “one of the big supporters of the Napa Institute,” in overturning Roe, referring to the current court as “the Leo court” and saying last year, “This is why we have the court we have today and the court America deserves.”

Francis has condemned abortion repeatedly, but refused to write off those who disagree. He welcomed Biden to the Vatican two years ago and, according to the president, told him he was a “good Catholic” who should continue receiving Communion — a direct rebuke to conservative Americans who said the sacrament should be denied him.

“We forget that to be pro-life is also to help the people completely, not just to defend an idea, not to embrace a political party that is pro-life,” said Francis’ U.S. representative, Cardinal Christophe Pierre, the apostolic nuncio, in an interview this fall about the “danger” of polarization, adding, “We are not just in favor of a few values.”

A value the pope does not share with the GOP is a love of capitalism. When Jorge Mario Bergoglio was elected pope in 2013, he was the first non-European in more than a thousand years and the first Latin American ever to ascend to the papacy. As archbishop of Buenos Aires, he rode the city bus and celebrated Mass in shantytowns, and had a harsh view of unfettered free markets that he was quick to express.

“We also have to say ‘thou shall not’ to an economy of exclusion and inequality,” he wrote in 2013.

He took a particularly dim view of trickle-down economics, a theory dear to the hearts of many American conservatives: “This opinion, which has never been confirmed by the facts, expresses a crude and naïve trust in the goodness of those wielding economic power.”

Those words must have arrived in Laguna Niguel like daggers to Busch’s heart. He had long connected capitalism with his Catholicism, telling a 2007 church group in Rome, “We have a right to have wealth.”

In his view, entrepreneurs helped others as they enriched themselves by providing jobs that lifted families out of poverty and gave individuals dignity.

“It’s easy to jump to the conclusion that if you have wealth and somebody else needs it, you should give it to them through redistribution,” he told a podcaster in 2017. “Really, we are … depriving them of their right to earn a living and to co-create with God.”

Busch’s economic views seem to have become more pronounced after he struck up a friendship with the billionaire libertarian Charles Koch, a fellow investor in a Palm Desert golf course.

Koch is not Catholic and as a libertarian does not share Busch’s concern with abortion and same-sex marriage. With his late brother, David, he funded climate denialism — something Francis has decried — and sought to undercut unions and minimum wage laws, which the church has traditionally supported.

Yet, Busch has said, “I tell him he’s more Catholic than most of my Catholic friends.”

Koch’s political network announced last month that it is supporting Nikki Haley, not Trump, in the GOP primary. Koch’s connection with Busch has proved beneficial for Catholic University, with his charitable foundation donating more than $17 million over the years.

In 2017, Busch invited Koch to speak at a conference on “Good Profit” — the title of a book by the billionaire — at Catholic University. Before the billionaire took the stage, a cardinal from the Vatican pointedly outlined church social justice teaching on fair wages, the rights of workers and care for the planet.

“The cry of the Earth and the cry of the poor go hand in hand,” Cardinal Peter Turkson told the conference. Taking the stage immediately afterward to introduce Koch, Busch told attendees, “We have to listen to both sides.”

“That is a really, really telling remark,” said Roberts, the former National Catholic Reporter editor, who was in the audience. “The cardinal is viewed as ‘the other side.’”

The ultimate impact of Busch and his allies is not clear. After a decade in power — longer than many had expected — the 87-year-old Francis has named most of the cardinals who will pick his replacement.

Ivereigh, the pope’s writing collaborator, said wealthy U.S. conservatives “make literally zero impact” in a global church of more than 1 billion people increasingly centered in Africa, Asia and Latin America.

“Napa Catholicism is just on another planet from where the church is,” he said.

But others said American Catholics will notice the rightward tilt of their church if they haven’t already. More than 80% of priests ordained after 2020 identify as conservative or orthodox, according to Catholic University research, and the sermons they preach, the counsel they give in the confessional and the ministries they support are likely to reflect their views.

“I don’t think we’re going to have a real schism, like in the Middle Ages with two popes, but a soft schism may have started already,” said Faggioli, the Villanova professor. He predicted Catholics will increasingly “parish shop” to find a church of like-minded people, a recognition, he said, “of incomprehension between different types of Catholics because of the culture wars.”

Does that prospect bother Busch?

The quiet meeting with Father James Martin earlier this year suggests at least a curiosity about those with opposing views. Busch didn’t respond to questions about what they discussed or the impetus for the meeting. Martin declined to share details, saying of Busch, “He’s a friend and plays an important part in the church.”

Subsequently, Busch scheduled monthly dinners for people of different political beliefs.

“I don’t think it means that he’s changing his views on theological or moral matters,” said his friend R.R. Reno, the editor of the religious journal First Things. “But, that doesn’t stand in the way of having conversations with people and having a pleasant evening.”

He said the first meal, in October, was “a failure” because most attendees held views in line with Busch.

On a fall Friday just before noon, about a dozen people gathered for Mass at the chapel in Busch’s law firm. Mounted on one side of the altar was a large painting of Francis’ predecessor, Pope Benedict. A small photo of the current pope was on a side wall.

Busch, still in New York, was not there. It was easy to see those who were present as part of the modern, diverse church Francis desires: A young Black woman with long braids was the altar server. A white woman in jeans read the Scripture. The priest was an Asian immigrant who arrived in an electric vehicle that he charged during the service.

He mentioned Busch’s New York procession briefly, but his homily focused on the main point in the Gospel reading for that day, a call for religious people to practice what they preach: “Beware of the leaven — that is, the hypocrisy — of the Pharisees.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.