He died training for L.A. teen crisis hotline. His parents want all to know the number

- Share via

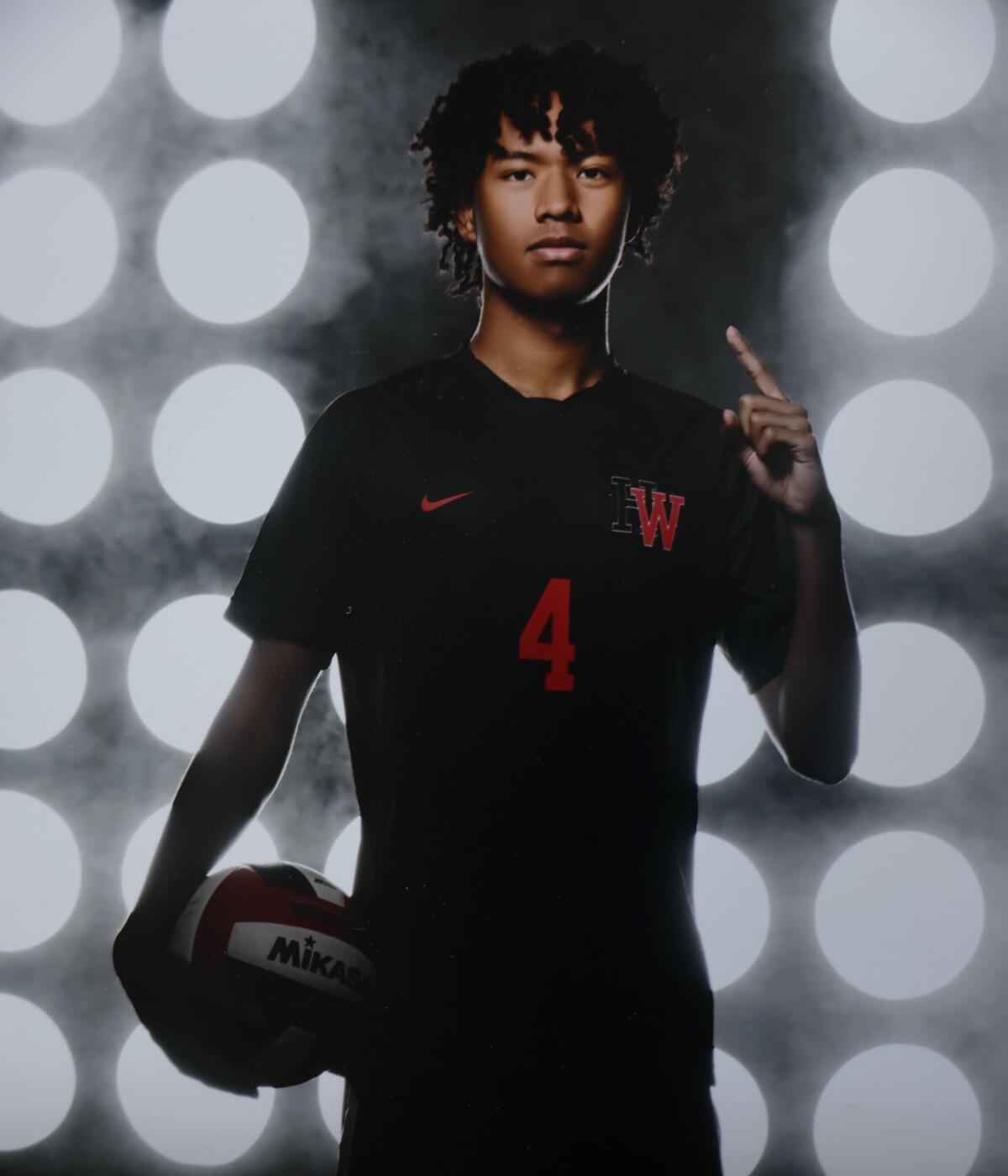

Among the first things 16-year-old Donald “Trey” Brown III picked up while training at Teen Line in the spring was how to ask another child if they were contemplating suicide.

This question is crucial, counselors at the youth-run crisis hotline say. Asking it directly saves lives, by naming the intense and often unspeakable desire to die that now haunts almost a quarter of American high school students, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

“People who are not suicidal will be like, ‘No, no, no, no, I would never do that,’” said Mendez, 16, one of the crisis line’s volunteer “listeners,” whom the organization asked to be identified only by her first name.

“But other people might say something like, ‘Well, maybe...,’” she went on. “A lot of people will test the waters to make sure you’re a safe person” to tell.

Because suicide is impulsive, the jump from inchoate longing to lethal intent can be sudden, the leap from intent into action even faster, studies show.

“One study found that 71% of attempts happened within an hour or less of [someone] making the decision, and a quarter were five minutes or less,” said Janel Cubbage, a suicidologist and prevention expert.

Yet as California’s teen suicide rate has spiked, school administrators have shied from the word. Now many all but forbid the acknowledgment of student suicides, despite state laws mandating evidence-based suicide prevention and decades of evidence proving silence causes harm.

“The No. 1 myth I’ve dealt with forever is, ‘If we talk about it, it’s going to happen,’” said Richard Lieberman, lead suicide prevention expert for Los Angeles County’s Office of Education, who also works closely with Teen Line.

Lieberman and other experts are adamant: Most suicides can be prevented. For adolescents, prevention often starts with other teens.

“Kids tell other kids what they’re gonna do,” Lieberman said.

This is the animating principle behind Teen Line, which connects children and adolescents in extremis with trained volunteers from Los Angeles high schools.

It’s also what drew Trey to the work. The Harvard-Westlake High School sophomore had long been a “therapist” for his friends. But after his classmate Jordan Park killed herself in March, he wanted to do more.

“He said he always meant to go up and say hi to her,” said his mother, Christine Brown. “He knew she was having a hard time and he felt responsible.”

Weeks later, senior Jonah Anschell died the same way Jordan had, followed almost immediately by Jordan’s father, Shaun Park. For Trey and other students at the prestigious prep school, the speed and the scale of the loss were dizzying. The fear of contagion — the viral spread of suicide through social groups — hung over the school like a miasma.

“I remember him saying after Jordan passed away, and then Jonah, there wasn’t a whole lot that they felt like they could do for each other,” Brown said. “When he got selected [for Teen Line] he was really excited. He felt like he could really be there” for his peers, she said.

To his parents, the skills Trey was learning and his passion for the work felt like an inoculation against a deadly threat. They called it “an extra layer of defense.”

The program’s training regimen was rigorous.

Sixty hours. No absences, no tardies, loads of homework. It was a lot for a kid who was already commuting from Santa Clarita to Studio City each day, and competing in varsity sports on top of his schoolwork.

But Trey was invigorated by the challenge, his parents said.

“He felt like that was his calling,” said his father, Donald Brown Jr. “He really wanted to have a purpose, to feel like he was making an impact, and that was his way of doing it.”

Then, in the midst of his training, Trey killed himself too.

::

i’m writing to you because i’m scared....this is the third time it’s happened this year, and i’m terrified it’s going to happen again. it probably will.

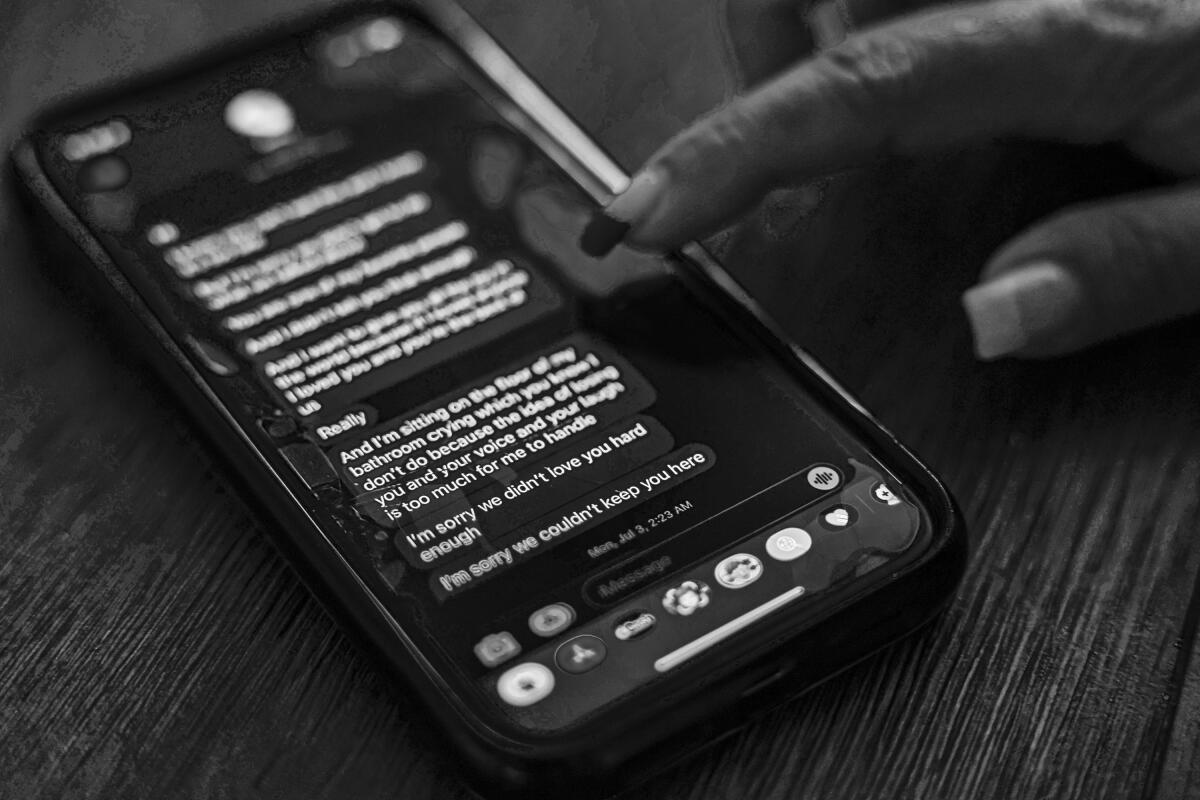

This is one of scores of texts that Trey has received since he died June 30.

Some friends still text every day, his mother said. Others write once, and disappear. Increasingly, the texts come from strangers.

“I have kids saying, ‘School’s not the same without you here. I miss you every day,’” Christine Brown said. “I’ve talked to a psychiatrist [about] the fact that these people are still texting, and she said, ‘You leave them alone. When they get ready they’ll stop.’”

Many parents fall silent in the wake of a child’s death by suicide. Grief, guilt and the intense stigma of suicide loss cut them off from the world.

“That’s part of the stigma that goes with it, that there must have been something wrong, the parents must have been neglecting them,” Trey’s father said.

But many others told The Times they were warned not to speak out about their child’s death, to receive condolences from their friends, or to memorialize them at school, the epicenter of most children’s social world.

Although they are not supported by evidence, such responses appear more common since the passage of California’s first school suicide prevention law in 2016.

Harvard-Westlake and other private schools are not governed by the law.

“Clearly, our school is not immune to the growing mental health challenges faced by an increasing number of teens nationwide,” said Rick Commons, the school president. “While we don’t have reason to believe that these tragedies are linked to anything that happened at school, Harvard-Westlake is embarking on an even more expansive effort to address the current crisis in teen mental health.”

Though the school’s administrators would not share details of their response to the recent student deaths, social media, student newspaper stories and interviews with parents suggest a massive, schoolwide effort — parts of which conform to evidence-based practices, and parts of which do not.

With few restraints on what they could say or do after Trey’s death, the Browns threw themselves into suicide prevention.

They have been in almost constant contact with Teen Line, promoting the number to anyone who will listen.

They also started giving out Trey’s phone number, urging strangers who might be in crisis to tell someone they were considering suicide, and to text their son to let them know after they did.

Texting had been one of the things that tied Christine Brown and her firstborn together. If she didn’t answer him promptly, he would hail her in all caps: BIRTHGIVER.

So, hours after Trey was found, and hours before his body could be identified, she went back to the place he’d last been alive to look for his phone.

The cellphone helps her hold on to him, and to the hope that others will reach out from the depths of despair, accepting what they’ve called Trey’s Challenge.

Because their son knew what to do, his parents said. He’d helped others to do it.

“That’s one of the reasons it caught us so off-guard,” his father said. “He had just done a session with his volunteer [supervisor] at Teen Line, and [she] was like, he’s just phenomenal.”

His sister even started wearing his Teen Line shirt.

“It has a number,” Christine Brown said. “That’s telling people — she doesn’t have to open her mouth, it’s telling people they can get help.”

::

Oct. 1 would have been Trey’s 17th birthday. Early that morning, dozens of people in Harvard-Westlake gear huddled in a tight scrum around his parents and three siblings, preparing for a charity walk in his honor.

“Alive Together: Uniting to Prevent Suicide” is an annual suicide memorial and fundraiser for Didi Hirsch Mental Health Services, which now runs Teen Line as part of its suicide prevention work.

The Harvard-Westlake contingent made up the single largest group. Most children had at least one parent by their side. Many came with both.

But even as they stood in solidarity with the Browns, parents remained frightened and ambivalent about what they or the school should do in the aftermath of so much death.

“I heard it’s impulsive,” said Dr. Kim Carvalho, a mom of two. “That’s what makes me as a parent really afraid. Because you think —”

“Well, they say it’s the model, perfect ones that fool you,” cut in fellow mom Kalika Yap, who runs a mindfulness group at the academy.

“That’s what I’m saying — everyone’s impulsive at that age.”

For these parents, the deaths felt closer and more personal than for many others at the tony prep school: Although Harvard- Westlake is majority white, two of the three suicides had been Asian or part-Asian children like theirs.

“I’m half-Asian, and I’m from Hawaii, and you don’t talk about your feelings,” Carvalho said. “You smile. Even if you’re hurting, you just suck it up and you don’t talk about it — you’re not allowed to.”

“We never told our kids, suicide runs in my family,” Yap added, nodding in agreement. “My husband was like, ‘Don’t say anything.’ He doesn’t want to give them the idea.”

In California, the suicide rate among Black and Asian youth has now overtaken the rate among those who are white, reaching about 10 per 100,000 and 8 per 100,000, respectively.

Trey was both.

Yet the way suicide threatens children of color, and how best to protect them, is not nearly as well understood as it is for white youth, experts said.

“Pretty much everything we have right now [in suicide prevention] is something that was developed and tested on primarily white populations, and they’re like, OK, this is evidence-based now,” Cubbage said. “But is it evidence-based if we don’t have evidence for everyone and if it works for everyone?”

Lieberman agreed.

“The vast majority who die by suicide are white, so we look at risk factors through a white lens,” he said.

What information does exist still doesn’t reach most parents — even highly educated and engaged parents such as Carvalho and Yap. The pair said they struggled to talk to their children about the suicides and fretted over how the school had handled them.

“It’s like a Pandora’s box, they don’t want to open it up,” Yap said of her children. “But then when they’re in school, everyone’s crying. They were able to have that assembly — but I also heard assemblies are not good.”

“My son said he couldn’t be part of that,” Carvalho said. “I remember one of the assemblies they had, [he] was like, ‘Oh my God, it was too much.’”

“One of [the mindfulness club]’s teachers said that when he found out they were doing an assembly, he was like, ‘Don’t do it,’” Yap agreed. “I don’t know why, but he said studies show” they’re harmful, she said.

Indeed, the evidence against assemblies is strong. Likewise, experts say schools should not close, and memorials need guardrails.

“The message to kids is, we totally have to memorialize your friend,” Lieberman said. But there are rules.

Rest in Peace T-shirts are gently discouraged — most guidelines say children who show up in them should be allowed to keep them on but asked not to wear them in the future. Candles, flowers and other temporary mementos should be cleared after the child’s funeral or public service, and classmates should be excused to attend such events if they want to.

Schools should have a written policy about candlelight vigils, graduation and yearbook tributes, trees, gardens, murals and other forms of permanent memorial that apply to all children who die, regardless of the manner, experts said.

But the best kind of memorial, Lieberman said, is one explicitly tied to suicide prevention.

For Donald and Christine Brown, that means continuing the work Trey left behind.

It means ensuring every child who knew their son knows this number: (800) 852-8336

Suicide prevention and crisis counseling resources

If you or someone you know is struggling with suicidal thoughts, seek help from a professional and call 9-8-8. The United States’ first nationwide three-digit mental health crisis hotline 988 will connect callers with trained mental health counselors. Text “HOME” to 741741 in the U.S. and Canada to reach the Crisis Text Line.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.