- Share via

SALINAS, Calif. — Francisco Rios stood contently watching the whirl of a Taylor Farms lettuce packaging assembly line, which was about to be dismantled and shipped off to Arizona for the winter. He would not be far behind.

A father of two who migrated from Mexico nearly 40 years ago and started as a cauliflower picker in the Salinas Valley, Rios said politics has been far from his focus as he works on packing up the factory for the move to Yuma.

“I don’t know any of these candidates,” he said when asked about California’s 2024 Senate race, “but I want one who believes in respect, liberty and equality.”

Many Latino voters in this corner of rural California believe politicians overlook them — perhaps more so than those living a little farther north in the Bay Area or down south in Los Angeles. Rios, who is now a safety supervisor, has always voted since becoming a citizen in 1998. He had heard Sen. Dianne Feinstein died, but had no idea who was running for her former seat even though one of the candidates, Rep. Adam B. Schiff, had just swung through town.

Candidates need to show up, campaign in Spanish and hone a message that focuses on opportunity for people who came to this country seeking a better life, Rios and others said.

Like many “in the Central Valley, our communities often don’t get a lot of focus and attention. A lot of the statewide candidates are focusing on large urban areas,” said Luis Alejo, chair of the Monterey County Board of Supervisors, who hasn’t endorsed in the Senate race.

“Among all the top candidates, I have yet to see any of them have a direct message for Latino voters. … Unlike some of the past elections, I think they need to come out with a really working-class economic plan.”

A plan that includes addressing California’s affordable housing crisis, which seeps far beyond the state’s big cities.

Rios, 62, owns a home in Arizona, where his wife lives year-round. While in California eight months during the year, he rents a two-car garage where he lives for $900 a month.

“There’s not even a bathroom,” Rios said in Spanish.

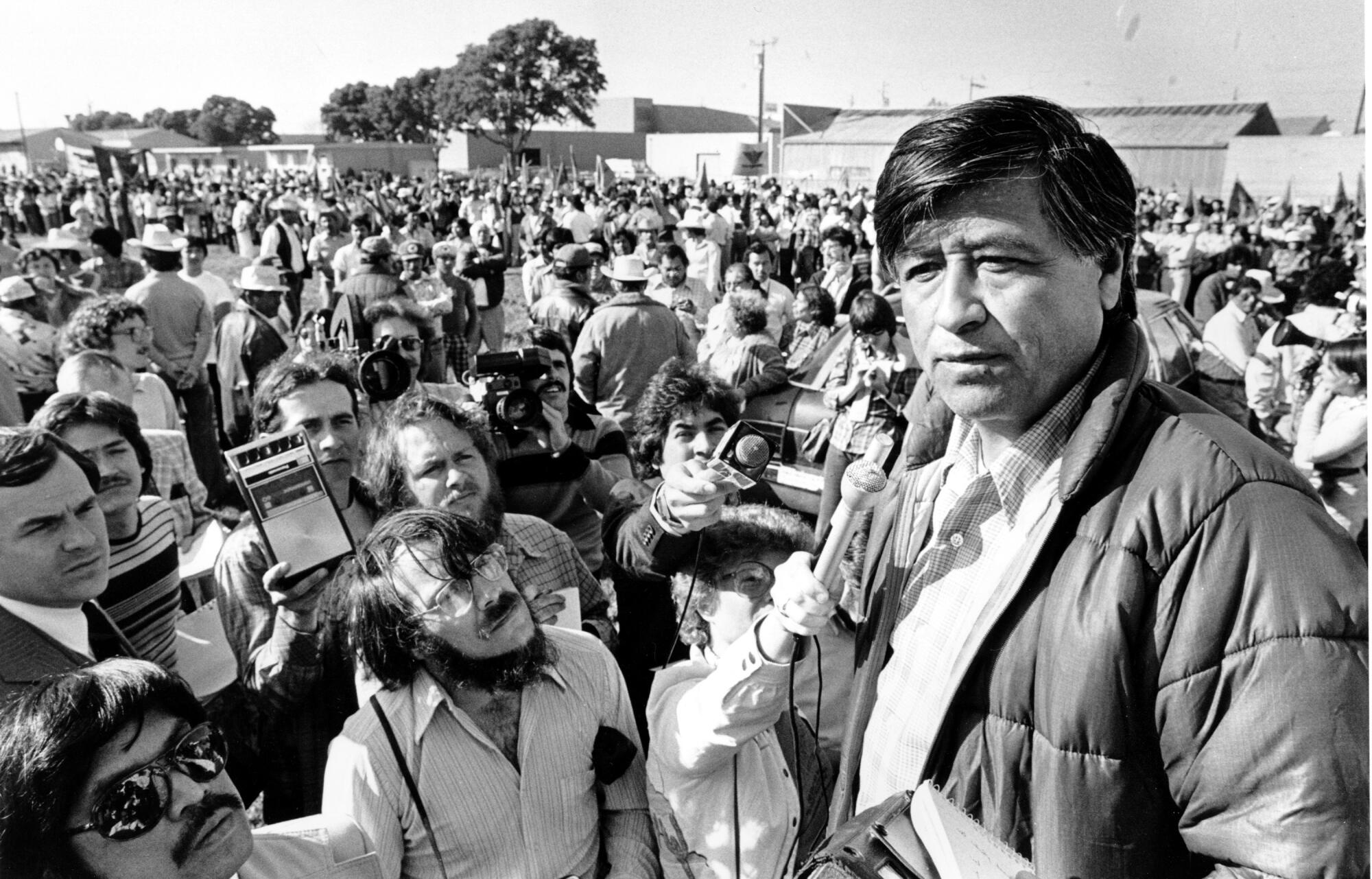

Known as “the Salad Bowl of the World,” the Salinas Valley — home to writer John Steinbeck — has been a cradle of political activism, where landmark voting rights cases opened up opportunities for Latino political leaders and the farmworkers’ rights movement took root. Labor leader and United Farm Workers co-founder Cesar Chavez was jailed for 21 days in Salinas in late 1970 for refusing to call off a boycott of lettuce grown by non-unionized workers.

Federal voting rights litigation in the late 1980s forced places like Salinas and Watsonville to do away with citywide balloting in city council races, which had made it harder for Latino and other minority candidates to win elections. Carving up the city into council districts ushered in a generation of Latino elected officials.

Simon Salinas, who in the 1980s became Salinas’ first Mexican American council member, suggested that the 2024 Senate candidates need to make inroads with Latino small-business owners if they hope to succeed in this part of the state.

“Those people are invested in dealing with bureaucracy. Those people can listen and say, you know, we need this to have more thriving Latino businesses,” he said. “They also want immigration addressed. They understand affordable housing. That’s an untapped source.”

The son of Mexican immigrants, Salinas worked in the fields before attending school and becoming a teacher. Later the Democrat served in the state Assembly and as a Monterey County supervisor.

He was at the National Steinbeck Center in Salinas’ downtown district, near its trendy coffee shops and the Taylor Farms headquarters, when Schiff visited.

Just blocks away, dozens of tents lined the railroad tracks — an encampment where some of the city’s roughly 1,000 homeless people stay. At the Schiff event, the crowd was constantly reminded by speakers that U.S. News and World Report had rated the city the seventh most-expensive locale in the country. The median monthly rental price is $2,395, according to Zillow.

“Everywhere I go, this is the issue people most want to talk about,” Schiff told the crowd of about 150.

With his backing of Burbank’s Rep. Adam B. Schiff, Speaker Rivas becomes the highest-ranking Latino elected official to endorse a candidate in California’s U.S. Senate race.

“How do we deal with homelessness, but even more broadly, how do we make housing affordable for people? How do we make it possible for people to live not only in a safe and secure environment and a nice home, but also live somewhere near where they work?” the Burbank Democrat said.

Along with his endorsement by state Assembly Speaker Robert Rivas, whose district includes Salinas, Schiff has the backing of prominent Latino politicians including Rep. Nanette Diaz Barragán (D-San Pedro), who leads the Congressional Hispanic Caucus, and former Los Angeles Mayor Antonio Villaraigosa, who focused his failed 2018 run for governor on visiting communities like Salinas.

The packed auditorium included several local Latino politicians. Still, Salinas said the event felt to him like it catered to white voters who’d come in from wealthier enclaves on the Monterey County coast.

Schiff talked about his work during former President Trump’s impeachment trials and spent a considerable amount of time decrying the high cost of living across the state.

Schiff found a receptive audience in Oscar Lopez, a local history teacher, and his wife, Marina Camacho, who is the Monterey County assessor-clerk-recorder. Both are naturalized citizens who came from Mexico more than 30 years ago, and they arrived at the Schiff event prepared to hear him out.

Lopez said he was firmly focused on what’s going to happen at the U.S. Supreme Court and who is going to support justices that are going to “protect our rights as individuals.” Camacho said her main concern was what “they’re gonna do for our local economy when it comes to the floods and fires.”

Both agreed that immigration policy looms large for them.

“For the immigrant family who may have the worry and the fear of deportation, they are the ones helping this economy grow because they put the food from this area on people’s tables,” Camacho said.

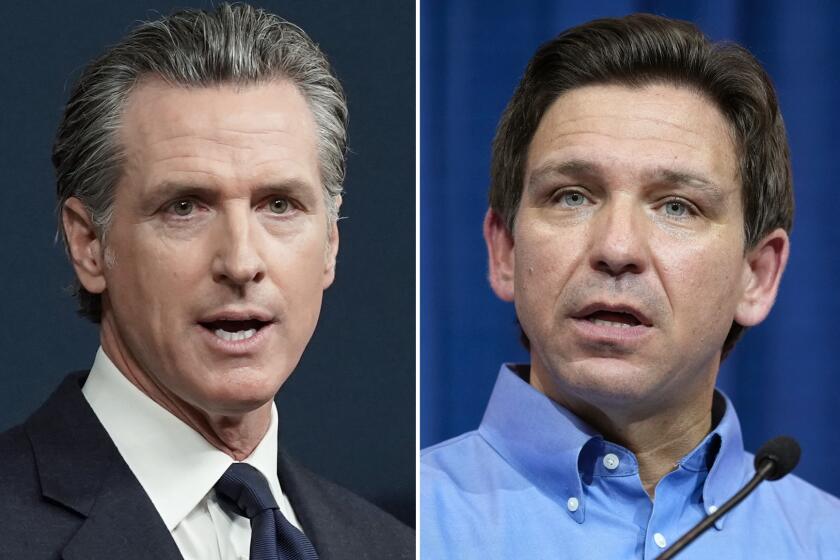

2024 presidential candidate and Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis agreed to a live televised debate with California Gov. Gavin Newsom, to be broadcast on Fox News this fall.

Recent independent polling of Latino voters shows that they — like most Californians across the state — are undecided in the Senate race. Schiff and Irvine Rep. Katie Porter, a fellow Democrat, were the two candidates with the most support. The top two candidates in the March primary advance to the November general election. The latest public polling shows Porter and Schiff tied, with former Dodgers star Steve Garvey, a Republican, and Oakland Democratic Rep. Barbara Lee trailing them.

The city of Salinas is about 80% Latino, while Monterey County is about 60% Latino, according to the latest census. The county has a huge Democratic voter registration advantage, and President Biden won here with 70% of the vote in 2020.

That hasn’t stopped some Republican candidates from flocking to the area.

Republican Florida governor and presidential candidate Ron DeSantis in September held a fundraiser at a local country club. The family that owns Taylor Farms hosted the campaign event, and many locals criticized the gathering given DeSantis’ immigration policies. Earlier this year, his administration placed migrants from the Texas-Mexico border on chartered flights to Sacramento.

“People in the community are often like: ‘I don’t know the candidates.’ But whenever they talked about what really triggered their emotion, it was immigration,” said Stanford University lecturer Ignacio Ornelas Rodriguez, a Salinas native who has studied the history of migrant labor in the area.

He recalled growing up with farmworker parents and there being a Border Patrol station in town. Though many Democrats favor the creation of a sustainable path to citizenship for many immigrants in the U.S. illegally, the failure by Democrats and Republicans alike to achieve that goal has elicited cynicism, Ornelas Rodriguez said.

Schiff didn’t say much on the subject while in Salinas. But at an event in Santa Clarita earlier this month hosted by the Coalition for Human Immigrant Rights, known as CHIRLA, he noted Democrats’ inability to meaningfully change the country’s immigration system. He — along with Porter and Lee, who were also in attendance — reiterated support for legislation that would expand pathways to citizenship for immigrants living in the country illegally.

CHIRLA’s political director, Fatima Flores-Lagunas, said Latino people living in rural parts of the Central Valley were struggling with the high cost of housing, the effects of climate change and uncertainty over immigration reform. She thought the candidates were doing a decent job appealing to these voters, but could do more to court them on social media and on their websites, where large sections describing their positions on issues appear only in English.

Porter, Lee and Schiff all spent some time in the Central Valley and other rural parts of the state this year, but their travel this fall has been limited by their duties in Washington.

“Let’s be honest, they all could be doing a better job,” Flores-Lagunas said.

At the lettuce packaging plant, Rios said, most of the roughly 1,200 people working there had some form of legal status and many had children and grandchildren who are citizens. The focus for him and many others was housing, economic opportunity, school safety and education.

Preventing Trump from returning to office remained important as well, he said.

Rios said his sister, who has legal status but can’t vote, helps him decide, but his hope is that the Senate candidates can do more events and interviews with Spanish language news outlets so he can sort out whom he’d like to support.

Ornelas Rodriguez, the Stanford lecturer, suggested another way Schiff could have better appealed to voters like Rios.

“He should’ve done that event in one of these fields,” he said — pointing out at a large expanse of farmland where the nation’s produce is grown.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.