Crime is down, but fear is up: Why is L.A. still perceived as dangerous?

- Share via

Skipp Townsend remembers a time when crime got so bad at Slauson Avenue and Crenshaw Boulevard that Metro buses used to barely slow down at the bus stop, where gang members were known to jump aboard and pick fights with passengers.

In those days, a seemingly endless spate of shootings and robberies left neighbors afraid to leave their homes, Townsend said, and a trip to the gas station in this corner of South Los Angeles would get you “pocket checked” by the men who hung out there, day and night.

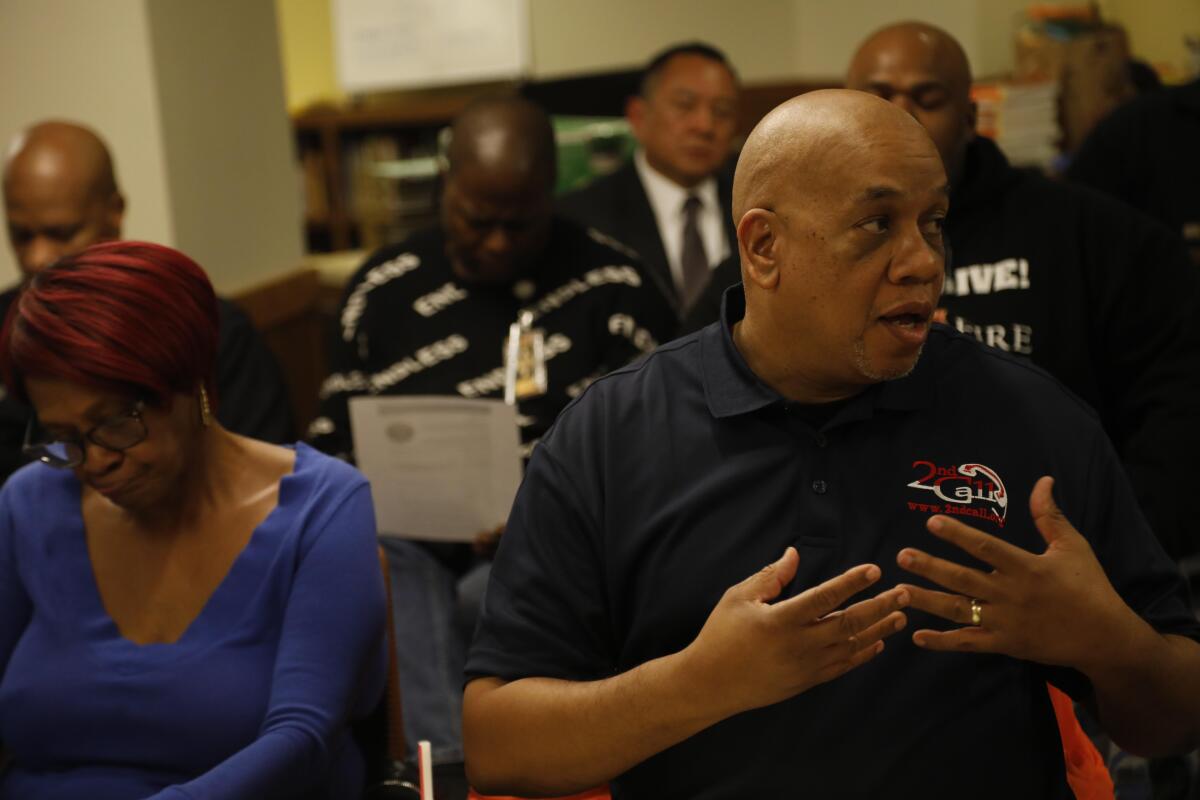

“I probably would’ve gotten beaten up or told to leave,” said Townsend, part of a loose network of gang interventionists who try to prevent retaliatory violence by tamping down rumors and connecting gang members with social services.

Though police statistics show crime is down in the surrounding area, Townsend often finds himself pushing back against claims that violence is spiking to levels not seen since the old days.

That disconnect isn’t just in South L.A.

Citywide, violent crime has declined nearly 7% compared with this time last year, with 1,650 fewer incidents reported as of Sept. 30, according to Los Angeles Police Department statistics. And yet, grisly murders and wild police chases still lead nightly TV newscasts. Social media remain flooded with images of youngsters in hoodies streaming out of high-end fashion stores with arms full of stolen merchandise.

Petty thefts are up by roughly 14%, but other property crimes — along with homicides, robberies and rapes — are all down from the same period in 2022. The number of people shot, including nonfatal incidents, has also declined nearly 16% citywide since last year. Historically high-crime police divisions such as Newton, 77th Street and Hollenbeck have seen double-digit-percentage declines in the number of shooting victims. Criminologists, police officials and others who study crime caution against reading too much into short-term swings, but the surge in violent crime of recent years has come amid a decades-long downward trend.

Bernard Robins, who was detained outside his parents’ South L.A. home by fellow LAPD officers, said the episode typifies the style of biased policing that’s practiced in some parts of the city.

The statistics may indicate the city is getting safer, but Townsend, who works with 2nd Call, a community based organization that serves formerly incarcerated people seeking to reintegrate back into society, said he sees “a lot of propaganda” on his social media feed about how it’s getting worse.

“People been doing smash and grabs, there were just no cameras around to capture it,” he said.

That so many people think of L.A. as less safe isn’t entirely surprising, he said, considering the city averaged more than 1,000 killings a year in the 1990s — more than three times as many as in recent years. Gang violence is still blamed for much of the bloodshed. But, Townsend said, the general public has a simplistic and outdated view of the dynamics of gang culture. Today’s violence is a far cry from the days of Bloods fighting Crips over drug turf, he said, explaining that gangs have become more fractured by infighting and less hierarchical, their membership constantly changing. And even when a shooting today does involve gang members, he said, it’s just as likely to stem from interpersonal dramas or perceived slights on social media.

The corner of Slauson and Crenshaw will forever be connected to the late rapper Nipsey Hussle, a towering figure in South L.A. who was working to revitalize this shabby stretch of churches, doughnut shops and car washes. Hussle was gunned down in 2019 outside the clothing store he owned at the intersection; his killer, Eric Holder, was later convicted and sentenced to at least 60 years in prison for the murder. Townsend said that while the surrounding Hyde Park neighborhood remains underresourced and violent crime is still a reality for some, the area is undoubtedly safer than it was even 10 or 15 years ago.

LAPD crime statistics back him up: Homicides in the area are down nearly a third from this time last year, and roughly 23% from the same period in 2021. And while property crime remains a problem, violence overall is down, including 51 fewer gunshot victims from last year.

State appeals court upholds the firing of two LAPD officers who admitted they were playing Pokémon instead of responding to a Compton robbery in 2017.

Data alone don’t shape perceptions of safety, according to Jorja Leap, a UCLA professor who studies gang culture. Leap said a person’s environment and biases are equal factors.

“You go to places like Watts and Boyle Heights, and they will actually tell you that it’s safer,” Leap said. “When they show the films of Nordstrom being broken into ... there is a sort of ‘Oh my god, that’s not supposed to happen here.’ Whereas if there’s a smash-and-grab at the Food4Less in Pacoima, then there’s the sense of, ‘Well, it’s a high-crime area.’ ”

A video of a flash mob burglary or a sideshow taking over an intersection can easily rack up millions of views online, creating the impression that such crimes are happening everywhere, Leap said, a cycle boosted by social media algorithms that promote outrage.

The “sensationalization” of high-profile, if statistically rare, crimes has “upped the ante,” said Leap. “People don’t differentiate violent crime from burglaries [and] smash and grabs. Yes, they’re stealing jewelry and designer handbags, but also people aren’t getting killed.”

Elections have fed the current hysteria around crime, Leap said, pointing to last year’s mayoral race and ads from billionaire developer Rick Caruso that painted a dystopian picture of crime and homelessness. Growing lawlessness was a constant theme at the Republican presidential primary debate last month in Simi Valley. Recent Gallup polling has found that partisanship plays a huge role in perceptions of crime and safety, with Democrats and Democratic-leaning independents far more likely to consider L.A. safe than Republicans and Republican-leaning independents.

There’s been a similar partisan split on the issue of zero-cash bail. Proponents say a new law, which took effect Oct. 1, is a step toward promoting fairness and addressing harm in the criminal justice system by no longer locking up people who haven’t been convicted of a crime simply because they can’t afford bail. But the policy has already drawn legal challenges, and LAPD Chief Michel Moore has joined police unions in coming out against the changes. Moore said in a statement earlier this month that the policy “offers little to no deterrence to those involved in a range of serious criminal offenses.”

A string of recent controversies have put to a test LAPD Chief Michel Moore’s quest to get his department into shape before stepping down in the next year or two.

With police saying that understaffing is limiting their ability to respond quickly to certain crimes, some residents have taken matters into their own hands, from hiring armed security patrols to shelling out as much as $150,000 for an “executive protection dog.”

Nationwide, a midyear study of crime across the U.S. by the Council on Criminal Justice found showed the country is on pace to record one of its largest annual declines in homicide, just three years after the country saw its largest ever increase amid the pandemic and the upheaval that followed the murder of George Floyd in police custody. At the same time, the report noted, crime levels levels at the halfway mark of this year remained 24% higher than through the first six months of 2019.

Places that have historically had the highest rates of violent crime, including South L.A., Watts and the northeast San Fernando Valley, remain hot spots. Black residents in the city’s poorest neighborhoods suffer the majority of the bloodshed, with Black children and adolescents in Los Angeles County killed by firearms at triple the rate of their proportion of the population, according to data from the Department of Public Health’s Office of Violence Prevention.

Despite the overall drop in shootings, the victims of recent firearm assaults have included a young Crenshaw High School basketball star, a gang outreach worker barbecuing at a park, and a 16-year-old boy who was killed in a shooting at a park in Granada Hills that also left a 2-year-old wounded.

Some observers say that even shootings without victims can cause secondary trauma for residents in those neighborhoods. And they dismiss observations about crime being down as a privileged, out-of-touch perspective of those who live in richer and safer areas.

Incidents in more affluent parts of town also tend to draw more attention. In one recent episode recounted in court documents, a pair of suspects masquerading as sheriff’s deputies broke into an AirBnB rental in the Hollywood Hills, armed with guns with green laser sights. The intruders tied up and pistol-whipped some of the home’s occupants before stealing a gun, a Rolex and one man’s passport. The LAPD eventually tracked the suspects to a downtown hotel, where they arrested five people, including two minors.

Violence in Watts prompts calls for unity in the community as gang interventionists partner with law enforcement and faith leaders.

In his weekly crime briefings to the Board of Police Commissioners, Moore has noted positive gains, but the LAPD chief has also warned that gun violence remains a major concern in a city awash in firearms; the number of shootings is still higher than in the pre-COVID years, he said.

“We still have far too much gun violence in this city,” Moore told the Board of Police Commissioners at its Oct. 3 meeting. The city had also experienced an increase in thefts, he said, a problem he has linked to a boom in online retail marketplaces that resell stolen goods. “This an area where our focus continues to be,” he said.

As with the causes of crime itself, the disconnect between statistics and public perception has long been studied and debated by criminologists and others.

Some research suggests that part of the problem is a feedback loop in which people have a tendency to focus on and remember negative information when it comes things like crime or the economy. Views about public safety often fall along political lines. Even though crime has been trending downward for more than a quarter of a century, in nearly every year since 1996 Gallup poll respondents have said they felt less safe than the year before.

Concerns about crime can be hard to disentangle from anxieties related to food insecurity, housing insecurity, climate and mental health, said Monique Alvarado, who lives in Glassell Park and works as a social worker. Statistics only tell part of the story of crime, without accounting for “emotional impact and an emotional trauma,” she said. That point hit home for Alvarado recently after a wounded man collapsed in the parking lot of her local watering hole, Verdugo Bar, asking for help after being shot nearby. He later died from his wounds.

“I can’t quantify the fact that now when I pass that bar, I’m going to know that that person died there,” Alvarado said.

Alex Alonso, a geography professor and gang consultant for Los Angeles district courts, said there’s no denying the impact that crime can have on communities, but he finds it ironic that the current conversation ignores the fact that homicides and gun violence are on the decline, even with the LAPD down more than 1,000 officers from a decade ago.

“Prior to COVID, we were at historic low numbers, and even then people were complaining,” he said. “I think a lot of people have amnesia and forget how many murders a year we used to have.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.