Clarence Avant’s political power: The ‘Black Godfather’ had the ear of three presidents

- Share via

As Clarence Avant headed into the hills north of Sunset Boulevard one night in the 1970s, a Beverly Hills police officer pulled him over for speeding.

Avant told the officer he was headed to his home in Trousdale Estates. The officer was dubious. The Beverly Hills neighborhood, one of the most exclusive in the country, was almost entirely white. Avant was Black.

“Look, I gotta hurry up,” Avant said. “Jimmy Carter is coming to my house.”

Now even more skeptical, the police officer said he would follow Avant home and write him a ticket — or maybe a few — once they got there. When the officer arrived and, stunned, saw the cul-de-sac swarming with Secret Service agents, he let Avant off the hook.

The story, recounted by two of Avant’s close friends, showed how a man known mostly as a barrier-breaking music executive also moved in some of the country’s most powerful political circles.

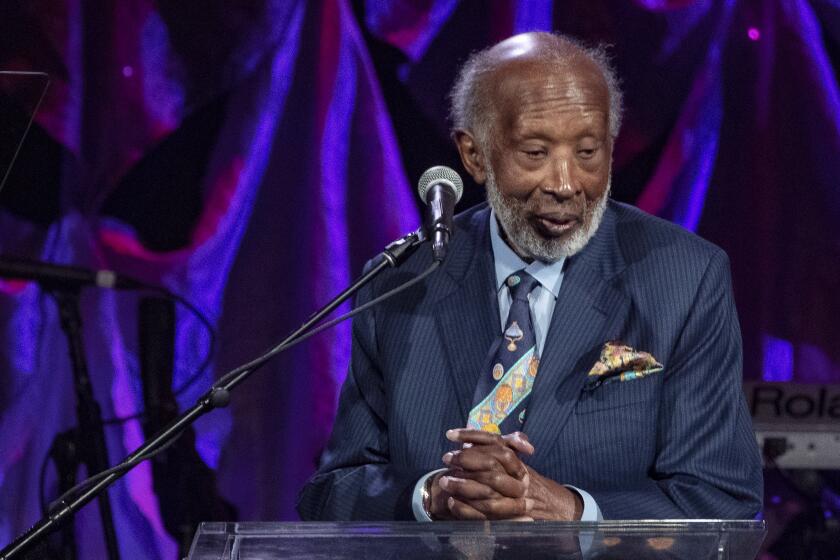

Avant’s death last month at 92 spurred an outpouring of tributes from celebrities as varied as musician and designer Pharrell Williams, NBA legend Magic Johnson and record producer Clive Davis. As a behind-the-scenes business titan, Avant signed singer Bill Withers, secured a Coca-Cola endorsement for baseball star Hank Aaron, and helped Muhammad Ali build an entertainment career after retiring from boxing.

But it was politics where the “Black Godfather” may have made his most permanent mark. Politicians from across the U.S. sought out Avant for his frank advice, his fundraising prowess and the weight that his endorsement carried among Black voters.

Avant, who didn’t make it past ninth grade and hated wearing a tie, had the ear of three presidents. He rose from a small town in North Carolina where the Ku Klux Klan was active to a powerful role in Hollywood, entertaining world leaders at his home and staying in the Lincoln Bedroom in the White House.

Money and celebrity were power, Avant sometimes said, and he was determined to use both. With a laser focus on fundraising, he leaned on his vast social and professional networks to help elect politicians who pursued economic and social progress for Black Americans.

Clarence Avant was a behind-the-scenes titan of managing, deal making and problem solving across the full spectrum of Black entertainment.

“You can’t go just one way, one color,” Avant said in “The Black Godfather,” Netflix’s 2019 documentary about his life. “You have to look at the whole system, and I look at the whole spectrum of this country.”

At their Trousdale Estates home, Avant and his wife, Jacqueline, hosted the first major Hollywood fundraiser for Carter, befriended Bill and Hillary Clinton and helped boost the profile of a little-known Illinois state senator named Barack Obama.

The couple attended White House state dinners, including a 1994 reception for Nelson Mandela, and helped organize glittering receptions in Los Angeles for international dignitaries, including the presidents of Tanzania, Sudan and Zambia.

An event at the Avant family home wasn’t a stodgy affair with canapes, friends recalled. They were actually fun, with good food, great music and a who’s-who guest list of politicians such as Tom Bradley, Hollywood executives including Lew Wasserman and Berry Gordy, and entertainers such as Sidney Poitier, Barbra Streisand and Harry Belafonte.

“Coming from where he had come from, he got an enjoyment out of seeing African American people climbing to the highest level,” said Clark Parker, who was friends with Avant for five decades. “He got that enjoyment out of seeing Tom Bradley, out of seeing Barack Obama, and I could go on right down the line.”

When Bradley launched his historic campaign for Los Angeles mayor in 1973, the Avants contributed a then-astonishing sum of $26,000 to his campaign and called on their wide social circle to raise tens of thousands of dollars more.

“He did everything in the world to get Tom Bradley elected,” said Bill Burke, a longtime friend of Avant’s, and the husband of former Los Angeles County Supervisor Yvonne Burke.

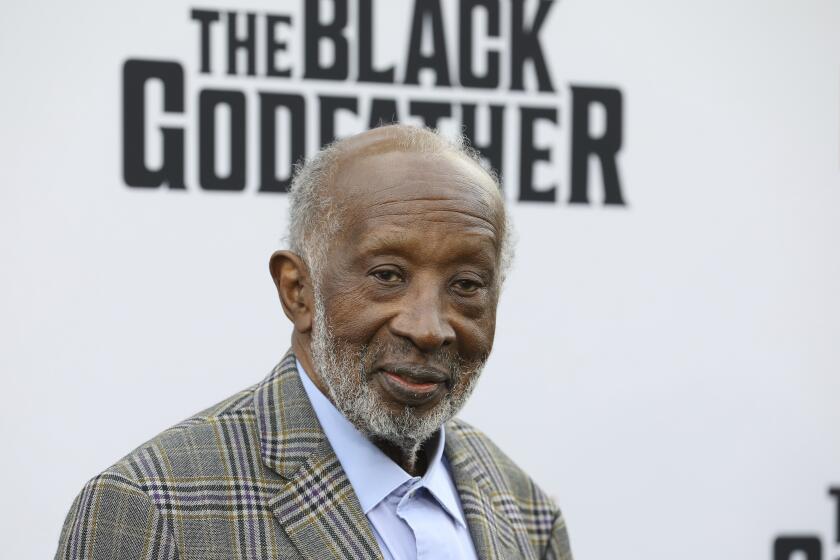

‘Black Godfather’ director Reginald Hudlin on Clarence Avant: ‘His effect is literally immeasurable’

Reginald Hudlin, director of Netflix’s Clarence Avant documentary ‘The Black Godfather,’ on Avant’s legacy, political impact and imprint on Hollywood.

Parker recalled hosting a fundraising lunch for Bradley in the board room of the insurance company where he was a vice president. Avant stood up, Parker said, and told the room: “Well, all you mother f—s, it’s time to open your checkbooks. When we leave here, we’re going to have $100,000 for Tom.”

They didn’t quite make the $100,000 goal, Parker recalled, but they raised about $84,000, the equivalent of more than half a million dollars today.

A candidate getting Avant’s stamp of approval was a sign of “instant credibility” for Black voters, said Kerman Maddox, a managing partner at the political consulting firm Dakota Communications.

Maddox first met Avant while collecting fundraising checks from lawyers, developers and executives on the Westside for his boss Maxine Waters, who was then in the California Assembly. Though gruff, Avant was always kind to the low-level staffer picking up the checks, and he sometimes gave practical advice, Maddox said.

When he learned Maddox was working on voter registration and get-out-the-vote efforts, Avant told him: “All that is great and wonderful, young man, but you have to learn to raise money. Once you learn how to raise money, you’re going to find yourself in rooms where things happen.”

Avant also wielded his influence beyond the Golden State. In the early 1970s, while driving through Georgia, he spotted a billboard for Andrew Young, a civil rights activist and former aide to Martin Luther King Jr. who was running for Congress.

Avant called him. The two men didn’t know each other. But they both knew getting a Black man elected to Congress in Georgia would be an uphill climb. The Deep South hadn’t sent a Black representative to Washington in nearly a century.

Avant told Young he would organize a fundraiser at Atlanta’s baseball stadium, featuring deep-voiced soul singer Isaac Hayes and the rock band Rare Earth.

“We had about 30,000 people in the pouring-down rain,” Young later recalled. “And he never sent us a bill.”

Young’s political career went on to span decades, first as a congressman, then as Carter’s ambassador to the United Nations and as the mayor of Atlanta.

The two men stayed close. Young often helped Avant raise money for local causes, including the UCLA International Student Center — a favorite cause of his wife, Jacqueline — as well as nonprofits that worked to help Black Angelenos, such as the Brotherhood Crusade and the local chapter of the Urban League.

Los Angeles businessman Danny Bakewell Sr., the publisher of the L.A. Sentinel newspaper, recalled Avant once picking up the phone and asking Young to come to a benefit for the Brotherhood Crusade, an appearance that helped put the nonprofit advocacy group on the map.

Young also connected Avant to Carter, then the governor of Georgia, who had declared during his gubernatorial inaugural address that “the time of racial discrimination is over.” Avant hosted the first major Hollywood fundraiser for Carter.

Avant was a key player in a Carter-led effort to boost the flagging finances of the Democratic National Convention. In 1976, Carter met with Avant and others in Hollywood, including actress Shirley MacLaine, to set up concerts “to spur voter registration and raise funds for the DNC,” the Chicago Tribune later reported.

In 1980, Jacqueline Avant told The Times that her husband was “dedicated to humanity, but especially the Black cause,” and had a keen eye for politicians on the rise.

“In 1976, he was saying, ‘Watch Jimmy Carter,’ when everybody else was saying, ‘Who is Jimmy Carter?’” she said. “Now he’s saying ‘Watch George Bush.’” George H.W. Bush was elected president less than a decade later.

Jacqueline was fatally shot at the couple’s home in Beverly Hills in December 2021. At the time of her death, the couple had been married for 54 years.

The Avants were also early backers of Bill Clinton. A fundraiser that Clarence Avant co-sponsored for Clinton in Washington was described at the time as the largest Black political fundraiser ever held. The party raised $650,000, dwarfing the $100,000 raised for Carter at an event Avant had also helped organize.

Avant liked Clinton and thought he really cared about helping Black Americans, rather than just making empty promises on the campaign trail, Bakewell said. And as Clinton weathered the Monica Lewinsky scandal, Avant stood by him.

Clarence Avant, the music pioneer known as ‘the Black Godfather,’ was saluted Monday by Bill Clinton, Jesse Jackson, Questlove and Clive Davis.

“When the Republicans were trying to run me out of town, Clarence looked at me and he said: ‘Don’t even think about it — this ain’t gonna happen unless you give in,’” Clinton said in the Netflix documentary. “He said, ‘Don’t spend a lot of time on this in public. Do your job. Let people see you working. It ain’t gonna happen.’”

At a time when few people wanted to be seen publicly with Clinton, Avant threw him a fundraiser and dug into his deep Rolodex to fill out the guest list, Bakewell recalled. Tickets cost something like $10,000 per couple, he said, and every table was full.

“Everybody wants to be there when the sun is shining,” Bakewell said. “Nobody wants to be there in the storm. But Clarence was right there.”

In the early 2000s, Avant called Burke and invited him to a fundraiser for a state senator from Illinois. Nobody in L.A. had heard of the guy, Burke said, but Avant said he was going to be president someday.

“I told him, ‘Clarence, that’s what you told me when Jesse Jackson ran, so I’m keeping my money,” Burke said. “I didn’t go to the reception, and that’s why I never built a relationship with Barack Obama.”

Obama wasn’t a household name when the DNC selected him as a keynote speaker at its 2004 convention. (In one headline, the Philadelphia Daily News asked: “Who the heck is this guy?”)

Obama recalled in the 2019 Netflix documentary that the speech wasn’t scheduled at a time when most people would see it. He called Avant and told him: “Clarence, they want me to speak, but I’m not even prime time.”

Avant said he called someone in presidential nominee “John Kerry’s camp.” The now-iconic speech aired at prime time. The 17-minute address turned Obama into a national star — and a 2008 presidential candidate — overnight.

“Did I ever think I’d see a Black president? Hell no,” Avant said in the documentary. “It wasn’t in the card game. When he said he was gonna run, I thought he was nuts.”

Loyal to his longtime friends, Avant backed Hillary Clinton in the 2008 primary. But his daughter Nicole made headlines by backing Obama, becoming one of the future president’s top fundraisers in Southern California. The family united behind Obama in the general election.

Obama said in the documentary: “I’d like to think that Clarence didn’t necessarily mind being proven wrong.”

Avant said: “Don’t think he didn’t rub it in.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.