LAPD asked about missed warnings with unit accused of stealing, turning off body cams

- Share via

In the week since the Los Angeles Police Department announced that the FBI has launched an investigation into a gang unit suspected of misconduct, department leaders have found themselves facing a familiar question: Should someone have seen this coming?

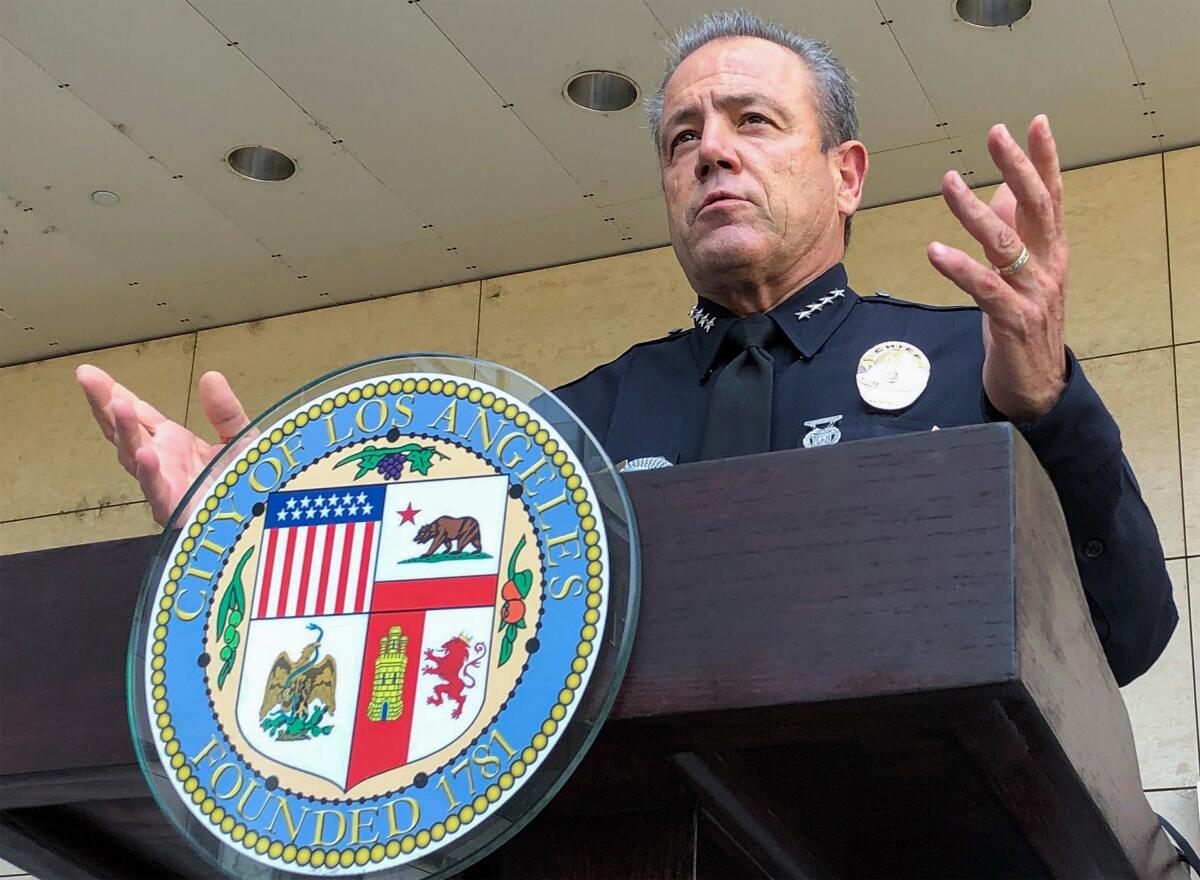

Chief Michel Moore said this week that the Mission Division gang unit has effectively been disbanded, with members transferred elsewhere amid accusations that officers were routinely turning off their body cameras — and possibly stealing from the people during traffic stops.

Sources briefed on the LAPD’s internal affairs probe, who requested anonymity to discuss the ongoing investigation, said the gang unit officers are also suspected of slipping Apple AirTags into some of the vehicles they stopped, allowing police to track them without a court-issued warrant.

After scandals in recent years involving other anti-gang squads and members of the Metropolitan Division, the broadening investigation into the Mission officers has led to renewed scrutiny of the LAPD’s management and oversight of its specialized units.

Those concerns surfaced at Tuesday’s Police Commission meeting, when several members questioned the chief.

“Is the department taking steps to ensure that anything that’s identified... is not being replicated in other areas?” Rasha Gerges Shields asked Moore.

The chief said the scope of the problem remains unclear, because the officers simply didn’t document certain stops, making it difficult for investigators to determine what happened and when.

At a media briefing that followed the meeting, Moore said that some of the involved officers are accused of theft, which prompted detectives to obtain warrants to search their department lockers earlier this month.

“We believe items were not returned to motorists or to people who were stopped and that resulted in a search warrant being authored, which is under seal at this moment,” Moore said. He said gang units from across the city were ordered to attend mandatory training at police headquarters this week.

Moore acknowledged a breakdown in supervision of the Mission unit, but said he’d seen nothing to suggest it’s a widespread issue.

The FBI has joined an investigation of several Los Angeles Police Department gang officers who are suspected of questionable tactics during traffic stops.

“I believe in the vast majority of the men and women of this department, I believe that they go out every day and they do outstanding work,” Moore said. “As an organization, we have seen failures in leadership, we’ve seen failures in leadership at times amongst peers, amongst first- and second-line supervision and sometimes regrettably even higher than that — but I will also say that those are rare episodes.”

Members of the Mission gang squad have been “administratively relieved of their responsibilities as gang officers,” Moore said, and replaced by officers from other units. The group’s sergeants and a lieutenant were also relieved of their command, he said.

Sources familiar with Mission Division operations, who requested anonymity because they are not authorized to speak publicly, said it has seen high turnover among senior staff, much like other LAPD outposts in the San Fernando Valley. Several supervisory positions remain unfilled.

Moore said the alleged misconduct came to light through an internal affairs investigation of a traffic stop last December, when a motorist claimed police pulled him over and searched his vehicle without consent or probable cause. A review of the unnamed officers’ other stops found instances where they had improperly switched off their body-worn cameras or otherwise failed to document the encounter, in violation of department policy.

As the investigation widened, Moore said, officials uncovered a pattern of similar deception by other members of the unit, formally known as the Mission Division Gang Enforcement Detail.

The Mission case presents a tricky predicament for Moore, who invited federal authorities to get involved. As a young captain, he was tapped to help clean up the scandal-ridden Rampart Division, several years before the signing of a federal consent decree that forced the department to make drastic changes. In the intervening years, the department dismantled or completely overhauled its anti-gang programs, to the point that gang officers today are among the most vetted in the department, Moore told The Times last year.

And yet, complaints of brutality and racial discrimination have continued to plague the revamped gang units, as have issues with body camera use.

When the LAPD first adopted body cameras eight years ago, they were sold in large part as a tool of accountability for officers, ensuring that they are carrying out their duties honestly and professionally. But the latest scandal has shed light on what some inside the department see as another, chronic problem: officers turning on their body cameras too late — if at all.

While some big city departments have entire units dedicated to auditing footage, in Los Angeles videos are usually only reviewed after a use of force incident or complaint.

The department does conduct routine compliance checks, but they are only meant to ensure that officers are allowing their cameras to buffer at the start of each shift and turning them on in a timely fashion — not to help improve the officers’ behavior. Longtime department observers say that without close monitoring, supervisors are unlikely to notice broader trends in problematic behavior.

Department officials contend that it’d be unrealistic for officials to review all of the roughly 14,000 body camera clips that Moore said are recorded every day.

Auditors from the four geographical bureaus perform spot checks roughly every four weeks by randomly reviewing eight gang unit stops “that don’t result in enforcement action.” Supervisors are supposed to ensure that an officer’s reports reflect what’s captured by their camera and look for potential red flags, including canned language in reports, over-reliance on a single confidential informant in multiple investigations, and a high percentage of stops labeled as consensual.

The LAPD is partnering with academic researchers to use artificial intelligence to study how officers speak to the public, but officials have signaled that the findings would be used solely for training purposes, meaning any misconduct uncovered would be unlikely to lead to discipline.

In a whistleblower lawsuit filed against the city in 2021, LAPD Capt. Johnny Smith raised the issue of officers routinely turning off their cameras, alleging that the department is letting those who fail to activate the devices off the hook. Smith, who claims he was demoted and transferred in retaliation for voicing his concerns, pointed to audits that showed near-perfect compliance in several Valley-area divisions, including Mission — results that now seem implausible in light of the ongoing investigation.

Under department policy, failure to properly use a body camera isn’t counted against an officer as long as they document “the reason for a late activation, early termination, or non-activation.”

Smith cited a May 2020 email to Moore and other senior staff, in which he wrote that “this body worn video issue could be our Achilles’ heel to the vision you have for this organization.”

In a follow-up message also cited in Smith’s lawsuit, Moore asked then-deputy chief Robert Arcos, “how are our systems full and true compliance?”

Smith said he was ignored by other top department officials. When he sent the audit to Elizabeth Rhodes, the civilian director of the LAPD’s Office of Constitutional Policing, her response was simply, “Thanks,” according to a copy of the email threads.

Mike Suzuki, a division chief at the Los Angeles County public defender’s office, said that instances of officers prematurely turning off their cameras to escape scrutiny “are not unusual.”

“We have often found that LAPD officers either prematurely deactivated their cameras or waited to turn them on until they’re making an arrest,” Suzuki said. “This creates a crucial gap in the video record, allowing officers to make up reasons for the stop and prevent public accountability for their actions.”

He added that his office believes the FBI investigation will reveal “that our clients are often the victims of pretextual arrests which are later misreported in police reports and testimony.”

Bernard Robins, who was detained outside his parents’ South L.A. home by fellow LAPD officers, said the episode typifies the style of biased policing that’s practiced in some parts of the city.

Last week, Mayor Karen Bass called the allegations against the Mission gang unit “very disturbing.” A few days later, she told a Times reporter she was satisfied that “the department is taking this very seriously,”

“As far as I know, this involves one station, but we have to get to the bottom of it to see,” Bass said. “I do think it is extremely serious and the fact that now the federal government is involved, I mean, if it was something minor, they wouldn’t be involved.”

Other top officials with oversight of the department have been wary of wading into the controversy.

Council member Monica Rodriguez, who chairs the public safety committee, declined an interview request, as did inspector general Mark Smith, whose office published a 2019 report assessing oversight of the department’s gang units.

Those who study policing say the allegations against the Mission officers may point to deeper problems in the LAPD. According to Max Felker-Kantor, a Ball State University professor who wrote a book on race and policing in Los Angeles, previous scandals that rocked the city’s police force were enabled by weak supervision and a bureaucratic obsession with making arrests and stops.

“The thing that is striking to me is the way that they continue to frame these sorts of actions within these historically we’ve called the bad apples framework,” Felker-Kantor said, in which police officials contend that “it’s not an issue of the department or the unit themselves, it’s the issue of these officers threatening to cause distrust.”

In the infamous Rampart scandal, gang unit officers were accused of shooting unarmed people, planting evidence and stealing drugs in the mid-1990s.

More recently, the reputation of the vaunted Metropolitan Division was tarnished in 2020 after some officers were accused of deliberately mislabeling youths as gang members. The scandal led to a revamping of the statewide gang database and the criminal prosecution of several officers. Most of those cases were later dismissed.

Officers in high-crime areas face pressure to seize guns and drugs, and those familiar with LAPD culture said that what can start as something small — a handful of officers who justify their use of improper tactics by telling themselves that they’re necessary to combat crime — can, if left unchecked, spread.

“Not documenting stops is not the same as planting evidence or physically abusing people,” said former LAPD Chief Charlie Beck. “Although if you’re doing the former it’s hard to get people to believe you’re not doing the latter.”

Times staff writer David Zahniser contributed to this report.

- Share via

Watch L.A. Times Today at 7 p.m. on Spectrum News 1 on Channel 1 or live stream on the Spectrum News App. Palos Verdes Peninsula and Orange County viewers can watch on Cox Systems on channel 99.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.