- Share via

Two friends walked into a diner to speak about the magic of a dead man.

“Amazing what he left behind,” said Garry Parmett, an autograph collector, halfway through an omelet. “He had the golden era of Hollywood in those shoe boxes.”

“Everyone who was anybody,” added David Kaye, a bookseller. “He had the whole cast of ‘The Godfather.’”

“Jesus,” said Parmett. “He knew where to go.”

“Dedication,” said Kaye, who finished his eggs and nodded for the bill.

“You couldn’t do that today,” Parmett said.

“No way,” said Kaye. “Impossible.”

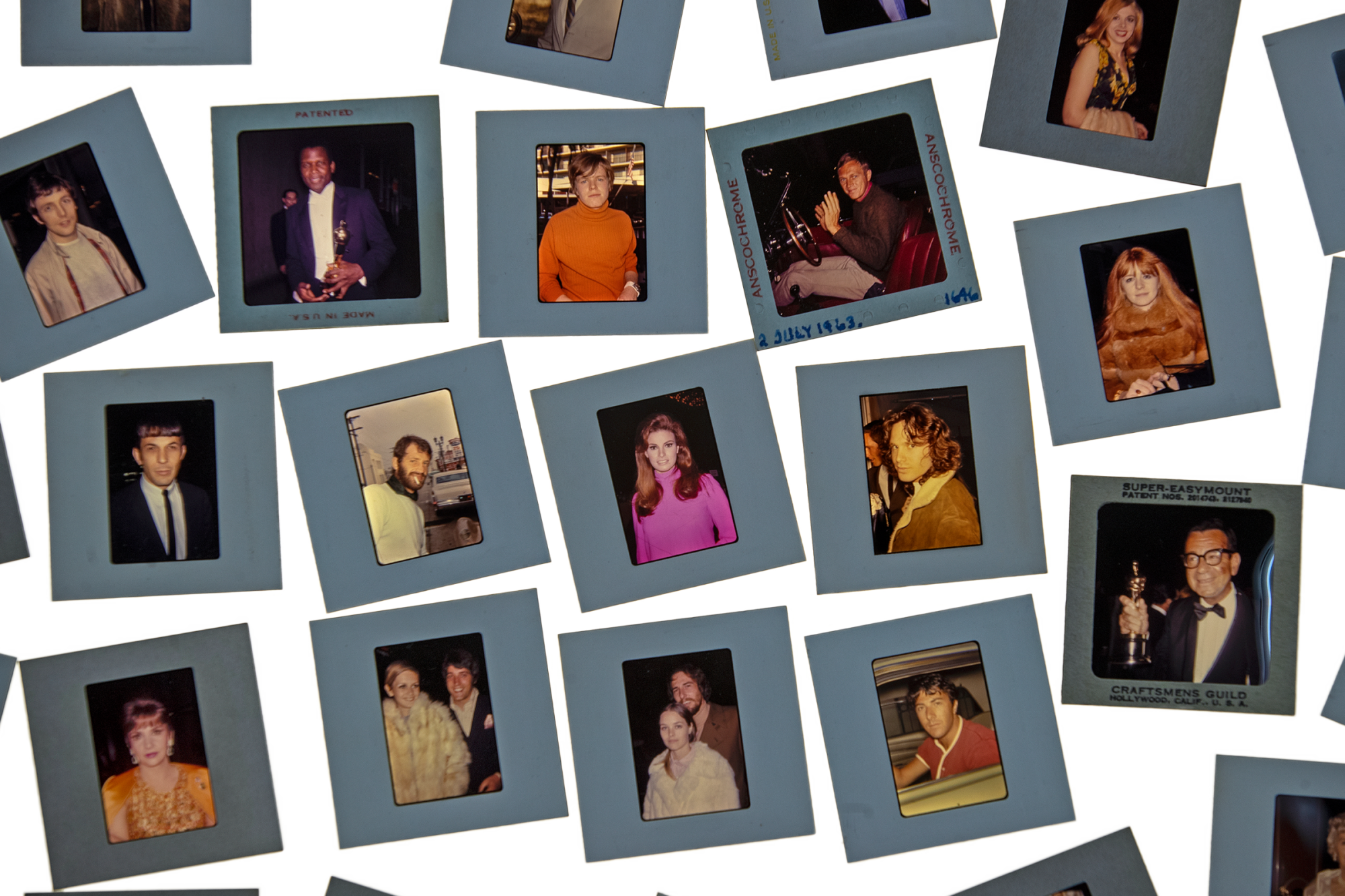

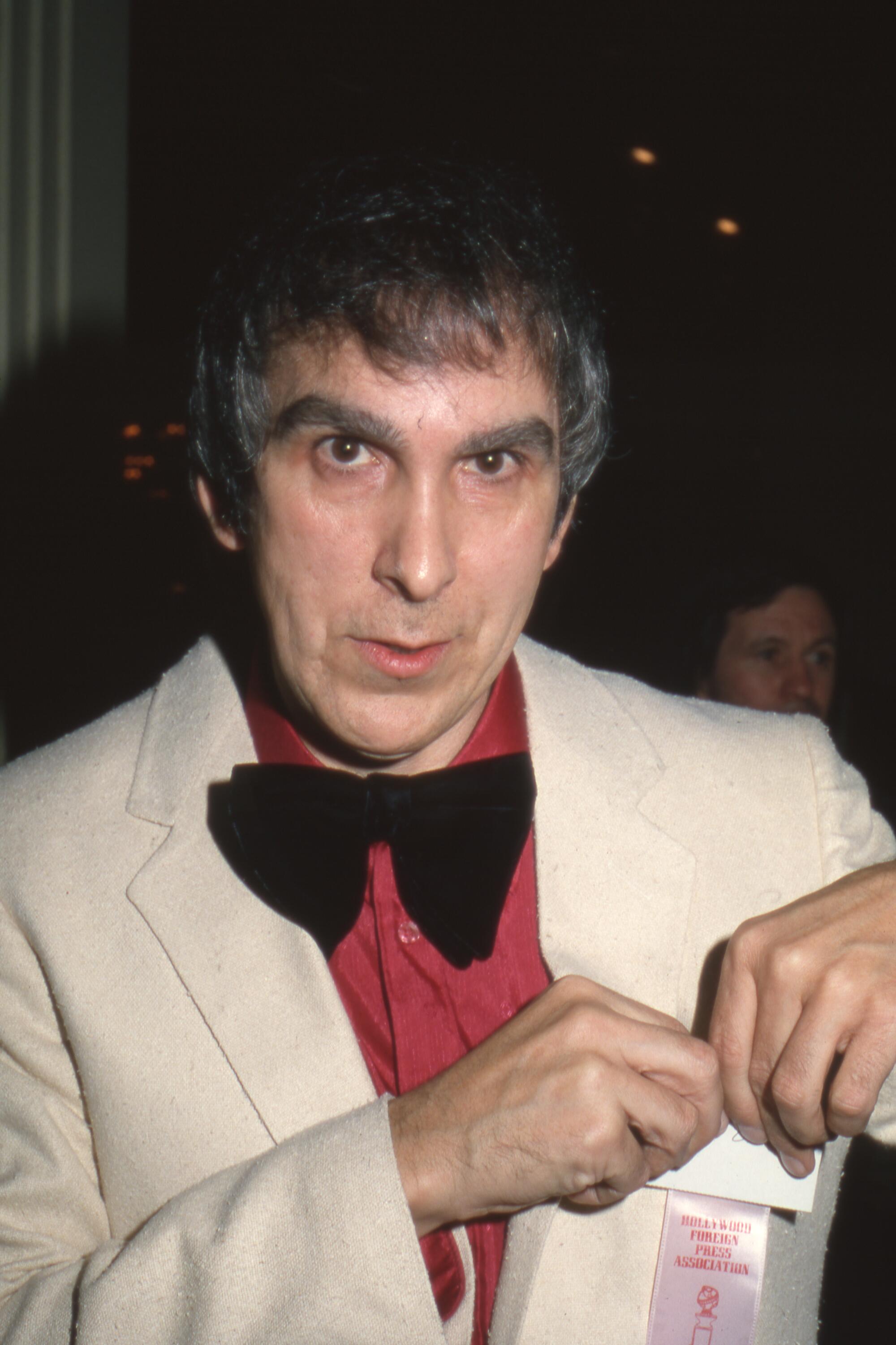

The man in question was John Verzi, who for six decades collected around 25,000 autographs and took more than 12,000 pictures of everyone from Audrey Hepburn to Brigitte Bardot to Jimi Hendrix and Alice Cooper. Then he disappeared. He ended up in a trailer park in Vegas, watching soap operas in the afternoon, playing casino slots at night, losing and winning in stretches, driving home in the ghost hours in a three-cylinder car his neighbor fixed from time to time.

Brigitte Bardot, left, attends an event promoting her film “Viva Maria.” The date written on the slide is Dec. 18, 1965. Jimi Hendrix is photographed in the back seat of a car. (John Verzi Collection/Los Angeles Public Library )

When he died in 2018, Verzi was 83, alone and, according to friends, nearly broke. His nephew took his ashes to Malibu and scattered them along the ocean in a cove beyond Cher’s house.

It was a fitting send-off. Verzi had yearned to be close to the stars since he was a boy watching horror flicks with his older brother. He sought entrance into their realm, not as an interloper or opportunist, but as a man with an ingratiating air who could recite the credit lines of every working actor. He was at home along the celebrity rope line at movie premieres, knew his way around the old Ambassador Hotel, kept a careful eye on the stage door at Merv Griffin studios and took his best photographs of people such as Charles Bronson and Tab Hunter at the unemployment office at 6725 Santa Monica Blvd.

He didn’t do it for money or recognition. He rarely sold a photo or a signature in what Bonhams auction house called “arguably the greatest autograph collection ever seen.” Verzi kept what he gathered in the dim sanctuary of the trailer he bequeathed in a handwritten will to Cherry Tolbert, his best friend at the Venice Post Office, where he had worked for 20 years, sorting letters, correcting ZIP Codes and rising to finance clerk.

How one woman’s obsession with a movie star led the Los Angeles Public Library to win an auction for 12,500 celebrity photographs—most of them never published.

Tolbert stood in that narrow home days after Verzi’s death, staring into rows of meticulously curated archives, the legacy of an eccentric who kept a prayer book and listened to Ben E. King and The Shirelles. She contacted Kaye, a memorabilia dealer, who sold the autographs for about $80,000 in a blind auction won by collectors David Wentink and Tom Kramer. The Los Angeles Public Library acquired the 12,500 photographs for $144,000 through a public auction last year at Bonhams.

Keanu Reeves told late-night TV host Stephen Colbert which two celebrities he’s asked for an autograph — and how they responded.

“I’ve become obsessed with” Verzi, said Wendy Horowitz, an archivist cataloging the pictures for the library’s photo collection. “This was his escape, and you can see on the faces of the people that a lot of them loved him. He got everyone. Movie stars. TV actors. Rock musicians. French actors. Joe Louis. Robert F. Kennedy. It’s amazing. But the historical value of this collection is the people he got who weren’t A-listers. Child actors. Obscure character actors. I mean he went to the premiere of the soft-porn ‘Flesh Gordon.’”

It was a life of getting to places fast, of tips, winks and confidences. Verzi drove a VW Beetle and traveled with cameras and colored index cards for autographs. He’d get a nod that Frank Sinatra might be in Beverly Hills having a drink or Lucille Ball was playing backgammon at Pips or Jim Morrison of the Doors had arrived at a West Hollywood theater to see “The Beard,” a play that was raided by police for a sex scene. Verzi kept tabs and followed whispers.

Bruce Lee, left, attends an entertainment industry event. The date written on the slide is Nov. 26, 1966. Elvis Presley sits in the backseat of his car as he leaves a movie studio lot. The date on the slide is June 7, 1962. (John Verzi Collection/Los Angeles Public Library)

“My favorite film was ‘The Women’ from 1939,” said John Paschal, a photographer who as a teenager befriended Verzi. “John knew I loved that movie. He asked me one day to drive with him to the old folks actors home in Woodland Hills. We walked in and he had a big smile on his face.

“He said, ‘See that little old lady over there? That’s Norma Shearer. She’s in your film.’ Norma was once the queen of Hollywood. She was married to [producer] Irving Thalberg and there she was sitting in a wheelchair with dementia.

“John knew everything about everybody in the movies,” Paschal said. “He respected that world. He lived and breathed it. ”

Verzi was a contradiction and a riddle. He was dignified but had a trigger temper. He was vain and fiercely territorial and would get depressed on days he didn’t get a picture. “He had to conquer,” Paschal said.

He was a savant who didn’t fit into the real world as easily as the make-believe one. In the 1960s, that was a refuge for a gay man who wore a magenta cape coat and appeared at the homes of aging film stars who reminisced about the times before the talkies when they glittered in black-and-white and seldom contemplated the impermanence of fame.

“John knew everything about everybody in the movies. He respected that world. He lived and breathed it. ”

— John Paschal

“He was very kind and gentle and easy to talk to, but odd, yet as a child it was a fun odd,” said Verzi’s stepniece Meagan DeHart, who recalled girlhood visits to her uncle’s West Hollywood apartment and the time she spent with him in Las Vegas years later. “He always slept on the floor. He’d drive us to the homes of famous people. I invited him to our home for Thanksgiving in 2008. He was exactly the same as when I was a child — his sweet, awkward self. A little bit on the spectrum.”

In a city where celebrities proclaim favorite restaurants with signed photos or TikTok reels, Michelle Phillips’ relationship with El Cholo stands out.

Tall and moving like a slight breeze through a window crack, Verzi had deep-set eyes and thick brows. In his younger days, before the comb-overs and the hand that lifted his mouth when he smiled, he looked a bit like Christian Bale, his face as smooth as his palms. He had a cosmetology license for electrolysis and as he aged, like the stars he had photographed, he felt the urge to recall that he had once been handsome. He needed glasses but preferred a magnifying glass. A friend said he covered the mirrors in his home so he wouldn’t have to look at what the years had thieved.

But then there’d be a flash of confidence.

“Don’t I look good today?” he would say.

He was overbearing to some. Actress Sylvia Sidney was reported to say when she saw Verzi: “Get that man out of here.”

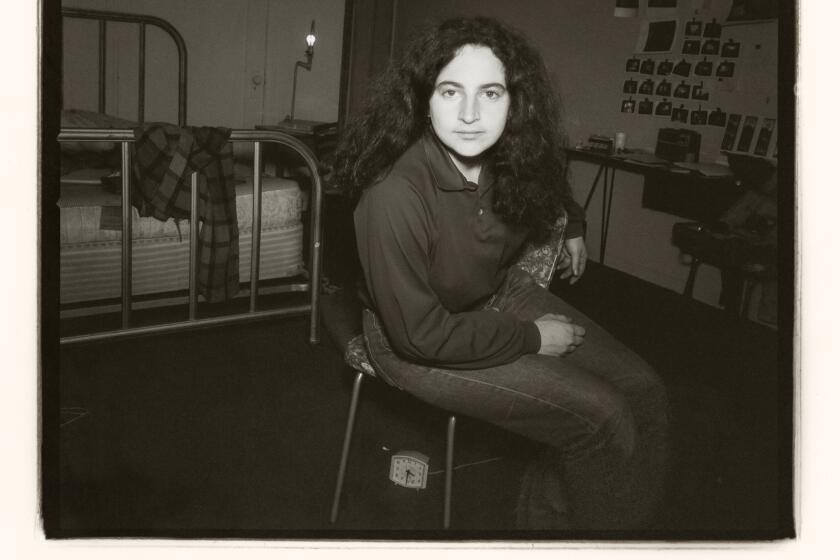

In 1975, art student Penny Wolin moved into the St. Francis Hotel in Hollywood and began photographing its residents. Forty-seven years later, those pictures make up her new book, ‘Guest Register.’

Verzi was born Jack Robin Verzi in Santa Clara County in 1934. His father, John Robert Verzi, the son of Sicilian immigrants, was the wealthy owner of hardware stores in the San Francisco area. His mother, Elizabeth, to whom he was very close, collected owl figurines and liked to drink, according to relatives. In the 1950s, Verzi studied elementary school education at Brigham Young University and moved to Hawaii to teach. He quit soon after and worked at a Honolulu hotel before moving to San Francisco and later Los Angeles in 1960.

“It wasn’t the pandemonium it is today with all the bodyguards and security. You could go out and see major stars without all these screaming crowds.”

— Garry Parmett

He grew estranged from a father who was dismayed that his gay, Catholic-raised son had quit teaching and abandoned a chance at a corporate job at Chevron. “My dad pretty much wrote him off at that point,” said Verzi’s stepbrother, Melvin, who refers to himself as a gun collector and a onetime professional gambler. “Jack — I always called him Jack — had an extremely high IQ. For a long time, he wanted to change his name from Jack Robin to John Robert Verzi Jr. My dad absolutely forbid it.”

Verzi’s relationship with his father — who divorced his mother, remarried and died in 2002 — was bruising and indelible. “He’d shut down any talk of family,” said a friend. But Verzi signed his will, as if in defiance of his father, as John Robert Verzi Jr. Despite the bitterness between them, father and son shared a love of photography: “When my father died, he had 21 cameras and thousands of slides,” said Melvin. “My whole life is documented in slides.”

Verzi arrived in Los Angeles when a matinee ticket to “Spartacus” cost $1.80. He copped a press pass through a friend and ventured across a city of fan magazines and scandals unfolding in a neverland of ballrooms, canyons and hushed bars where Clark Gable might wander out of a restaurant and sign autographs for a few collectors waiting by his car. Verzi photographed Sophia Loren in a fur coat and diamonds at a movie premiere; caught Marilyn Monroe — smiling as if she recognized him — leaving a dinner party honoring director Billy Wilder; and, in a candid moment in 1961, got Janet Leigh, one year after she starred in “Psycho,” powdering her nose in a car while Tony Curtis sat nonplussed in the driver’s seat.

Verzi seemed to know everybody. Through the post office, he had access to addresses, including the home of Stan Laurel, half of the 1930s Laurel and Hardy comedy team, where Verzi was invited into the living room. He was as prolific as he was bold. Over 11 months in 1960 and 1961, Verzi, who often traveled to New York and Europe and showed up at Hollywood awards shows in a tuxedo, photographed nearly 300 celebrities including Cyd Charisse, Paul Newman, Ronald Reagan, Warren Beatty and Judy Garland.

Judy Garland, left, is shown after her sold-out performance at the Hollywood Bowl. The date on the slide is Sept. 17, 1961. Warren Beatty stands in a parking lot. The date on the slide is Oct. 28, 1961. (John Verzi Collection/Los Angeles Public Library)

“It wasn’t the pandemonium it is today with all the bodyguards and security,” said Parmett, owner of Celebrity Circle, a memorabilia business. “You could go out and see major stars without all these screaming crowds. What do you have now? Reality TV people with no talent showing off outlandish lifestyles, these so-called influencers. It’s very, very sad. There’s no class anymore.”

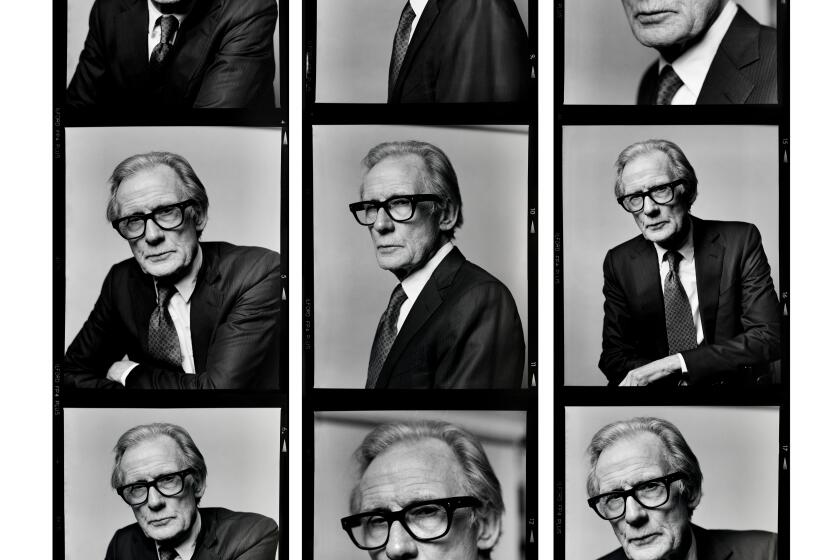

A few of the best celebrity portraits published by The Times in 2022.

Parmett was getting into the autograph scene when he met Verzi, who was “not a particularly friendly guy,” he said, adding, “He didn’t like anyone on what he thought was his territory.” But Parmett admired Verzi for “pounding the sidewalk for decades.” If you wanted to get a signature or a photo, Parmett said, you had to be as patient and diligent as a magpie or a fisherman.

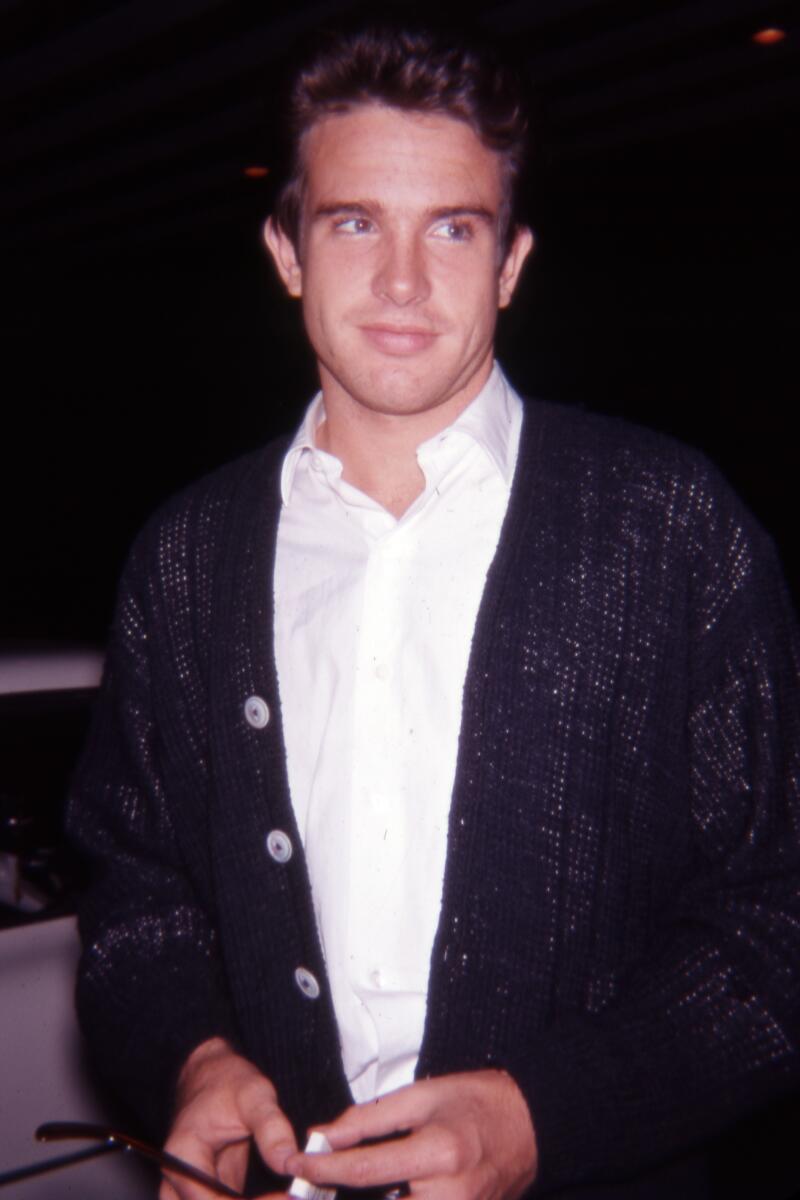

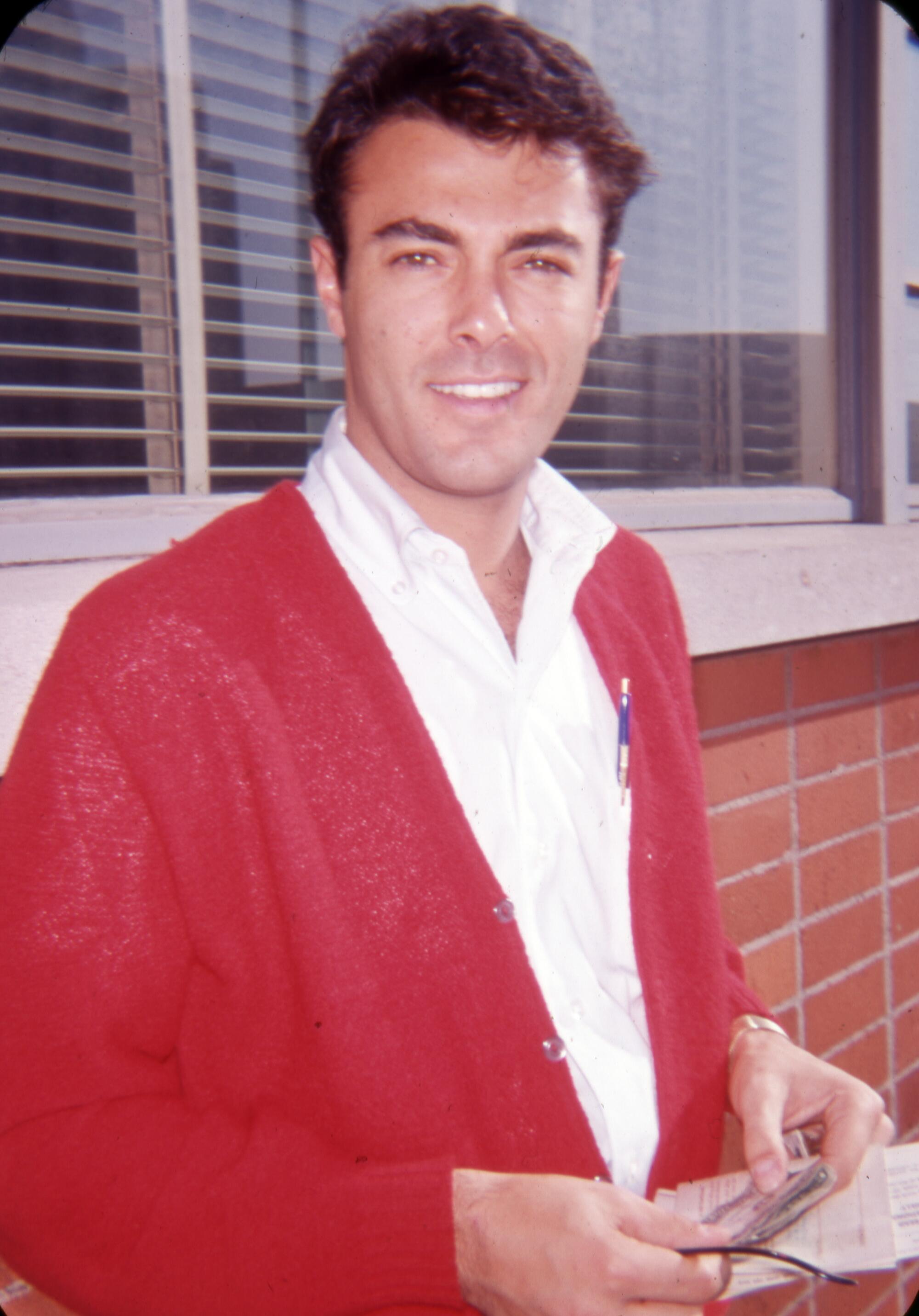

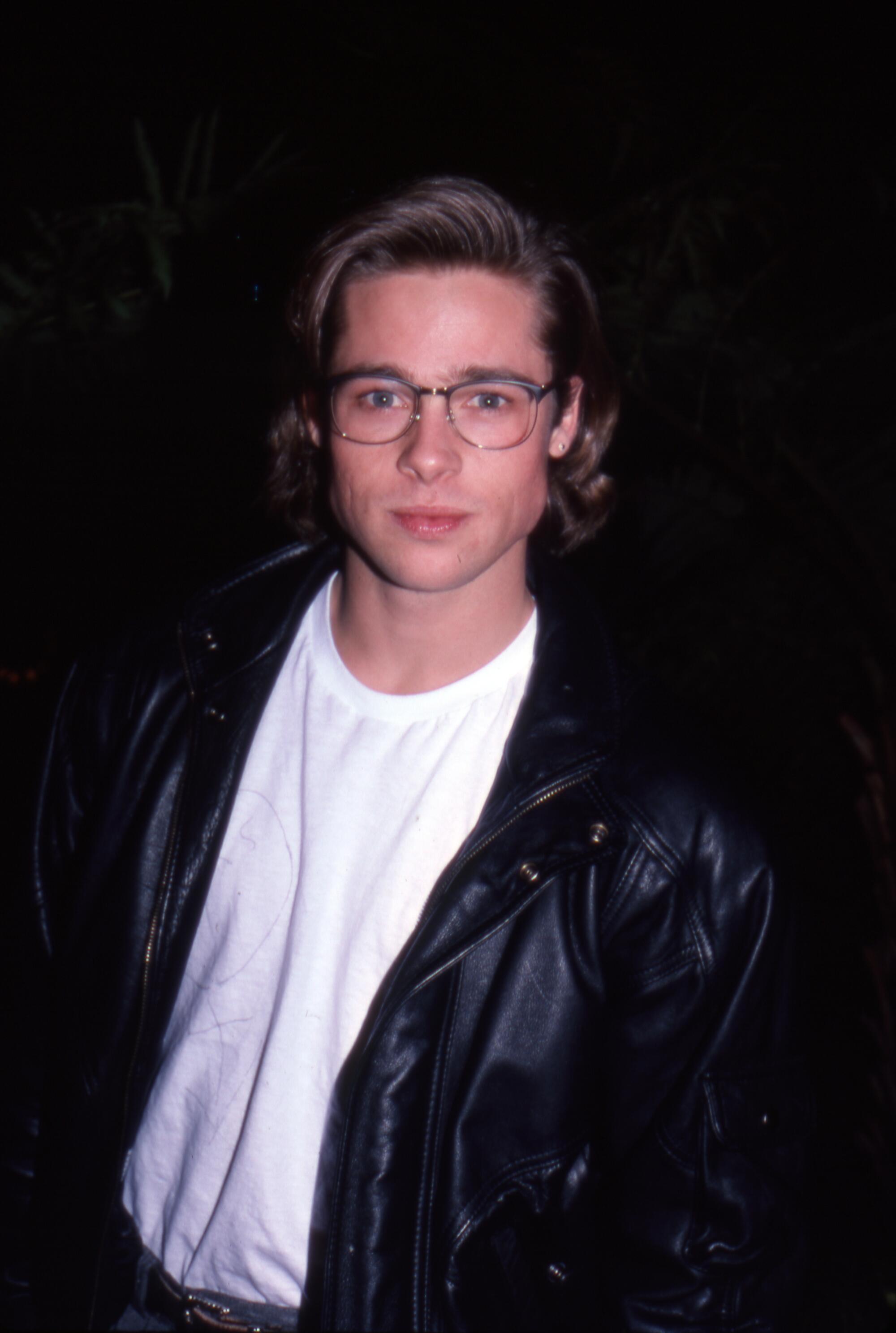

By the late 1960s, when independent filmmakers were challenging the old studio system, Verzi, who wore bell bottoms, Hawaiian shirts and loved to roller-skate, lived in West Hollywood and took a job at the post office. His camera caught the faces of change: Sharon Tate, Dennis Hopper, Mick Jagger, and into the 1970s with George C. Scott and Diana Ross and the 1980s with Johnny Depp and Winona Ryder. He understood the Hollywood gaze that over time widened and grew mercenary. His collection became a private conceit, scrupulously named and dated in the penmanship of a monk, stored in boxes and metal bins like a man in a film hiding riches in the shadows.

“He loved photographing beautiful men,” said Horowitz, pointing to a slide in her office in the Central Library downtown. “Here’s a matador. He shot valets. Bodybuilders. He loved Matt Dillon. He has a lot of shirtless pictures of John Schneider” (of “The Dukes of Hazzard).

The collection includes no lover or partner. “I think he was pretty much in the closet until he died,” a relative said.

The L.A. City librarian oversees more than books. His world encompasses the complexities, joys, possibilities and sadness of Los Angeles.

Paschal was in his late teens when he moved from the Valley to Hollywood, a “starstruck” kid with a camera. “John took me under his wing. I’d be at Spago or someplace and I’d call John and say, ‘Natalie Wood’s here with Laurence Olivier.’” He added: “John was much older than me. He knew I was gay. He’d speak more freely around me. ‘Oh, he’s good-looking.’ But John was always respectful. He was a nice man. I’m in my 60s now, and trust me, being young and gay in the ‘70s I met a lot of pervies. He was not.”

“It’s a little sad, maybe,” said Paschal, who runs a studio that specializes in Hollywood and entertainment photography. “The way his life turned out.”

“He loved photographing beautiful men. Here’s a matador. He shot valets. Bodybuilders. He loved Matt Dillon. He has a lot of shirtless pictures of John Schneider (Dukes of Hazzard).”

— Wendy Horowitz

Verzi received a large sum of money and quit the post office in 1989. The amount, according to relatives and friends, was between $300,000 and $400,000. The source is unclear. Melvin said Verzi inherited nontaxable securities from a rich man he had befriended.

“That’s when he bought his place in Vegas,” said Paschal.

Verzi moved into a trailer at the Riviera Mobile Home Park (Space 97) east of downtown Las Vegas. He gambled at night at Club Fortune Casino and other venues beyond the glare of the Strip. He’d eat complimentary dinners and wander to the slots. “He was exacting. He knew those machines,” said his stepbrother. “His winnings for a time far outnumbered his losses.” He’d sometimes order breakfast at Blueberry Hill Family Restaurant, but he spent his days in front of a Philco TV watching soap operas amid newspapers, a Rudolph Valentino movie poster, a painting of the Immaculate Heart of Mary and laminated pictures of his casino jackpots.

Rudy Ray Moore, left, is photographed in front of an adult movie theater in Hollywood. The date on the slide is Sept. 28, 1975. Ann Dvorak is shown in the backyard of her Hawaiian home. The date on the slide is Oct. 8, 1971. (John Verzi Collection/Los Angeles Public Library)

“He kept his trailer dark with thick curtains so the sunlight wouldn’t bother him,” said Victoria Millett Ramirez, a friend who worked with Verzi at the post office and who, with Tolbert, would send Verzi money when his luck turned bad. “He’d say you can call me but not at such and such a time because he was watching his shows. He loved ‘The Young and the Restless’ and Judge Judy.”

John Schachtschneider lived in a nearby trailer. A union man retired from the heating and air conditioning trade, Schachtschneider would fill the tires, change the oil and repair Verzi’s Geo Metro, which replaced his VW Beetle: “He’d come home from gambling around 1 a.m. He didn’t smoke or drink. He told me he lost $750,000 gambling. Gamblers are used to ups and downs. He kept to himself. Friends?” He laughed. “Me. He left me his car when he died. I cleaned it up and got 900 bucks for it.”

Sharon Tate’s life and death became an alluring portrait upon which to hang our what-ifs and darker fascinations.

Verzi never showed Schachtschneider his autographs or photographs. “I had no idea,” he said. “He liked looking stuff up on the internet. He looked up stuff about me. He found my dad’s name and other stuff I didn’t even know about me.”

In 2006, Verzi contacted a distant cousin, Shawn Doyle, a genealogist and a former nuclear plant security guard from Oswego County, N.Y. Verzi had years earlier made trips to Europe to trace his ancestry and was intent on exploring his maternal grandmother’s side of the family, which hailed from Glencolumbkille, a village in County Donegal on the west coast of Ireland. Doyle said Verzi was an exacting researcher who wrote emails — many in the early morning hours — the way people once wrote letters.

“John had gone to Ireland many years before. He took pictures of thatched cottages and these aged people,” said Doyle. “He got stories from them. He took Kodachrome color slides. They would talk about this relative from California who drove a nice rental car and wore good clothes.”

The email exchanges between Doyle and Verzi — who wrote in caps — reminisced about ancestors going back to the 1800s. Other times, Verzi would share a personal note: “I fell asleep listening to 1920s jazz music. Now, I’m starving! I will get cleaned up, go out into the windy night, dine & gamble. Till tomorrow ... John.”

By then, much of Verzi’s life was the solitary unraveling of the past — even his boyhood when he and his brother, Jerry, watched horror films and collected biographies of stars. Jerry, who joined the Air Force and died in 1996, resented his brother for being gay. Verzi escaped such intolerance and travails by listening to Brenda Lee or Bobby Darin. The real world, though, often intruded. On Dec. 30, 2013, Verzi, who collected a post office pension and Social Security, posted on Facebook: “Pay off my debts!”

For a man who took thousands of pictures, Verzi posted only three on his Facebook page. A white wooden fence running along rose pink blooms. A black-and-white portrait from his youth. And another portrait tinted in amber, his hair combed forward, his eyes fixed on the lens. Posted three years before his death, the photograph is of a man decades younger, an image one hopes will survive, like the line from a Paul Simon song: “A time of innocence, a time of confidences. Long ago, it must be, I have a photograph. Preserve your memories; They’re all that’s left you.”

“I think he had a tough life,” said Tolbert’s daughter, Tina. “But he never sold any of his photographs or autographs. They were precious to him. That’s heartbreaking to me. He’d go to the casinos and the cheap cafes. He was struggling at the end. He’d go without air conditioning to save money. My mom would cut his hair. Her heart went out to him over what happened with his family.”

Flawed heroes, dark angels and dashed dreams: Why L.A. and noir are synonymous

Verzi’s autograph collection alone, according to collector David Wentink, might have gone for hundreds of thousands of dollars if Verzi had broken it up and sold it in pieces. A rare autograph of Al Lettieri, a character actor who appeared in “The Godfather,” was worth about $7,500, Wentink said. Collectors like Verzi, he added, “could change their lives in days or weeks but they just can’t let go. The pain of giving up something is more powerful than the rewards they might receive.”

Verzi’s nephew, who asked not to be named for privacy reasons, said his uncle “was happy going to the casinos and gambling all night. He had friends all over the country. He never seemed down. He was a simple man. He’d say, ‘Never take me to the Strip.’ He hated it there. He loved the little life on the opposite side of town.”

Verzi was pronounced dead in his trailer at 11:25 p.m. on May 18, 2018. The cause was complications from hypertensive heart disease. Cherry Tolbert had not heard from him in days. The police were called and Tolbert, who had the will, arrived a day or two later, followed by Verzi’s nephew. “I took some of his record collection and a Shirley Temple and a John Wayne autograph,” the nephew said. “I didn’t take the slides. I thought, ‘Nobody looks at slides anymore.’”

In the following weeks, Tolbert and Ramirez went through the trailer, collecting shoe boxes of autographs and metal bins of slides, including those of about 200 French actors and pop singers, which Verzi kept in a cabinet by the refrigerator. Tolbert was left everything, including rosaries, a prayer book and a picture of a child who appeared as if a ghost in an old frame. Verzi asked in the will that she make a “generous gift” to the Shriners Hospitals for Children “in my name and that of my mother.”

Tolbert didn’t know the value of the pictures and autographs. She contacted Kaye, who owns a bookstore in Woodland Hills and has been dealing in memorabilia for nearly half a century. Her inquiry led Kaye to immerse himself in a stranger’s painstaking obsession.

“You’re always skeptical when you get a call like that. ‘Oh, my relative died and I’ve got a great collection,’ said Kaye. “But I don’t dismiss anyone. Cherry sounded like a nice lady. She wasn’t overselling.”

Tolbert emailed photos of the autographs to Kaye. “I see Grace Kelly. Very rare. Humphrey Bogart. Very, very rare. I see Bobby Kennedy. This is intriguing. I got into my SUV and drove to the trailer.” Kaye spent months going through the collection. The autographs were sold in bulk to Wentink and Kramer; many are now for sale on eBay for $15 to $25, including some by a dealer who goes by “brucelovestheocean.”

The photographs will become part of the library’s permanent collection. Before Tolbert died in January, Tina said her mother donated money to Shriners in the name of Verzi and his mother. The amount was not known.

“He probably dedicated every spare moment of his life to this,” said Kaye. “He was my most unique find.”

One of Verzi’s pictures shows him sitting next to Jane Wyman, a 1950s movie star and former wife of Ronald Reagan. She is wearing a blue embroidered dress with a pearl necklace and red lipstick. She and Verzi, dressed in a pinstripe collar shirt, are holding open a book with a black-and-white portrait of a much younger Wyman, eyebrows arched, hand to her face, bracelet on wrist; her past a splendid, vanishing vapor against the present.

Verzi looks toward the camera. He is there but he knows his place, as if a bird content to peer from a branch into the garden.

More to Read

Sign up for This Evening's Big Stories

Catch up on the day with the 7 biggest L.A. Times stories in your inbox every weekday evening.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.