The latest group to get special attention from college admissions offices: Men

- Share via

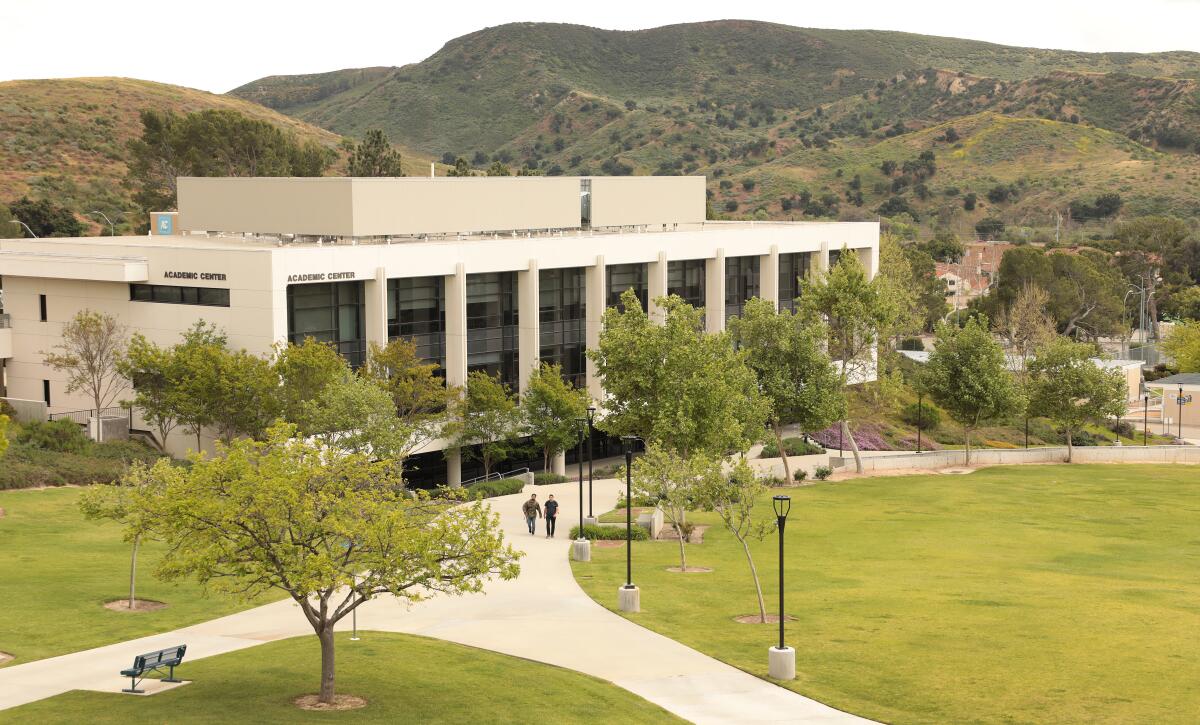

For a while, Moorpark College had few problems enrolling male students.

In 2015, men made up more than 48% of students at the community college in Ventura County. But then they started disappearing, until they comprised just 43% of the student body by fall 2020.

Most worrying was the number who failed to return for a second year of college, especially Latino and Black men. While about 80% of white men continued their education beyond their first year, just 50% of Black men and 71% of Latinos returned in 2020.

To help keep Black and Latino men enrolled, the college has introduced a slew of initiatives, including “equity lounges,” summer trips to Africa and seminars for professors on how to best teach men. The school has asked every department to gather data on its male students and has developed counseling and mentoring programs for Black and Latino men.

“The men [here] don’t come from a position of privilege,” said Amanuel Gebru, vice president of student support at Moorpark. “They need more help.”

Women now make up about 58% of U.S. college undergraduates, according to the National Student Clearinghouse Research Center, and each year far more women are enrolling in higher education than men. The trend is especially acute for Black men, with about 138,000 fewer Black men enrolled in college last year than in 2017.

Although college enrollment is down by 1.11 million overall since 2019, according to the Clearinghouse, the situation with male students has become so worrying that some colleges have started to treat men as a group that needs additional support, and to seek ways to both attract male students and keep them enrolled from one year to the next.

Like Moorpark, many schools have begun to focus on attracting specific groups of men.

California’s 116-campus community college system has boosted support of its African American Male Education Network and Development program, or A2MEND, to attract and retain Black men. The effort is meant to improve the climate for Black male students by providing one-on-one mentoring and meeting spaces to create a sense of community. It has given out $700,000 in scholarships to Black men, according to Gebru, who also is the president of the A2MEND board.

“We’re making efforts, but we haven’t done enough,” Gebru said. “There’s a lot of initiatives and conversations about creating safer spaces in the classroom for Black male students, but there isn’t policy to say we have to hire more Black faculty and staff at these colleges.”

Just 7% of U.S. faculty members are Black, according to the National Center for Education Statistics, and Moorpark College said just 2% of its faculty is Black. The U.S. population is 13.6% Black.

Other colleges throughout the country, too, have turned to recruiting men.

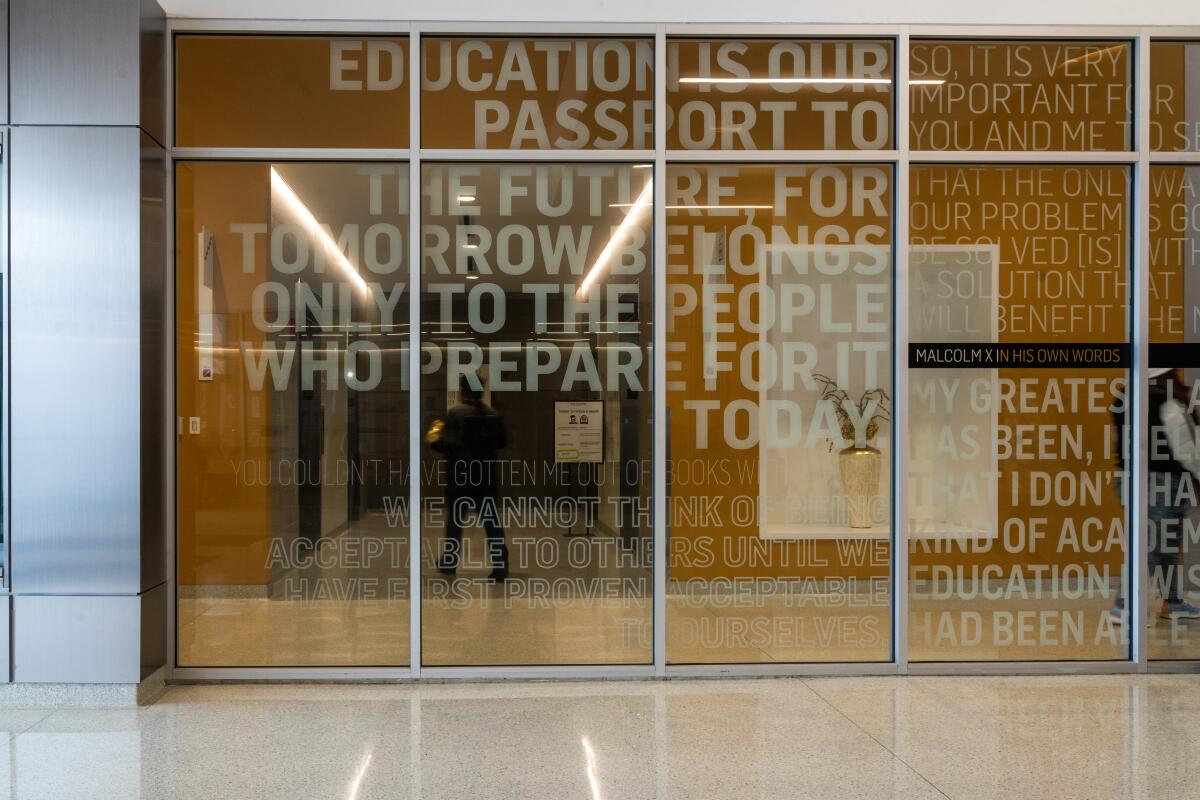

In Chicago, Malcolm X College has an enrollment that’s three-quarters female. At a recent recruitment event for area high school students, it appeared one challenge is marketing college as an option at all.

“The thing is,” given its high price and questions about its value, “college might be a scam,” said Donje Gates, an 18-year-old senior at Bogan Computer Technical High School on Chicago’s South Side. He’s considering going to a trade school instead.

College leaders at Malcolm X started a mentoring program that pairs an instructor or other employee with two Black male students, leading to increased retention. While 43% of Black male students dropped out between the fall of 2021 and the spring of 2022, 93% of the few dozen men in the mentoring program stayed, President David Sanders said.

Along with financial and academic obstacles for many, breaking through often conflicting messages to men and boys about their education is another challenge.

“Rigid conceptions of masculinity, that include anti-school sentiments, harm their well-being, and contribute to adverse outcomes in education,” a task force of the American Psychological Assn. notes on its website.

The task force is working to change such messages so teachers and others better understand male students and their educational needs earlier, especially if they are boys of color.

“Teachers may consciously or implicitly expect lower academic performance from Black and Latino boys regardless of their prior academic achievement,” it said. “This can result in a self-fulfilling prophecy.”

Ioakim Boutakidis, a task force member and a California State University Fullerton professor of child and adolescent studies, said he believes more educators would be inclined to help boys and men if it weren’t for mistaken assumptions about male privilege. Even his own colleagues have expressed skepticism about the need for more focus on male students, he said.

“I go where the data tells me to go,” said Boutakidis, the father of two adolescent boys. “If I care about equity gaps, then I’ll put my efforts where the equity gaps are biggest. I’m not trying to bring an ideology to this.”

Boutakidis suggested that the easiest way to start to close those equity gaps is to focus first on men of color, who are less likely to attend college than white men.

New Jersey’s Montclair State University last year launched the Male Enrollment and Graduation Alliance to increase the number of male Black and Latino students. Forty percent of the students at Montclair State are male, 36% are Latino and 13% are Black.

Boys and men in economically disadvantaged neighborhoods tend to focus more on other things than college, said Vaughn Smith Jr., a 23-year-old Montclair State senior. Smith, who is Black, said he decided in high school that he wanted more from life and chose a college path. Although most of his male high school classmates did go to college, he said, many of them have since dropped out.

Similar trends can be seen in Appalachia, said Rick Childers, an alumnus of Berea College in rural Kentucky who mentors male students from the region. Berea College has 18% fewer male students now than it did in 2019. He said the students he meets still face outdated ideas about masculinity.

“You’re encouraged to go better yourself, but my dad would always call me ‘college boy,’ ” Childers said. “It was confusing, because I thought it was what I was supposed to be doing. But then there’s this resentment.”

This story was produced by The Hechinger Report, a nonprofit, independent news organization focused on inequality and innovation in education.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.