- Share via

One firefighter made off with a Los Angeles Fire Department cellphone last year and used it to solicit a prostitute while on duty. He then abandoned his dispatch post at the department’s downtown communications center, which handles 911 calls, drove to a hotel near Los Angeles International Airport and had sex with her before returning to work.

A second city of L.A. firefighter drove with a blood-alcohol level nearly 2½ times the legal limit, resisted arrest and committed a battery on a law enforcement officer, according to LAFD disciplinary records on the 2020 incident.

In a third case, three LAFD firefighters reported in 2020 that their captain kicked a homeless man in the head with his steel-toe boot while the man was lying motionless, the department records show. One witness said the blow was so hard that he heard the man’s teeth “clank together.”

How many of the firefighters lost their jobs?

None.

The LAFD almost never terminates firefighters, even those who have committed crimes or other types of egregious wrongdoing, a Times investigation has found. Their misconduct is detailed in the department’s own disciplinary files as well as court records and other public documents.

Not a single firefighter was fired in 2021, the last year for which comprehensive disciplinary information is publicly available, according to department records. Not for domestic violence. Not for falsifying medical records. Not for making racially offensive remarks or publicly promoting an alleged hate group.

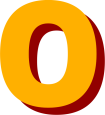

Disciplinary procedures dragged on for so long that some firefighters were able to retire before any punishment was imposed. Others escaped with their jobs after a Board of Rights panel, made up of three fire officials, imposed lesser penalties, such as suspensions. And in many other cases, the department issued reprimands or no discipline at all.

“How in the world does nobody get fired for some of these things?” asked Jimmie Woods-Gray, president of the Fire Commission, the civilian panel that oversees the LAFD, in response to questions about the cases reviewed by The Times. “If you were in any other job, you would be fired. What is it that keeps firefighters from getting fired?”

High-profile misconduct cases exposed by The Times renew criticism that the Los Angeles Fire Department is lax in disciplining firefighters.

The 2021 cases were compiled in an internal review of disciplinary procedures by the LAFD’s Office of Independent Assessor, which reported its findings to the Fire Commission. The report shows that the LAFD meted out no punishment in more than 90% of the roughly 1,900 disciplinary cases that were closed in 2021 and from 2017 through 2019, combined. Figures for 2020 were not compiled by the assessor.

Of the 648 cases closed in 2021, the Fire Department sustained the allegations in just 112, or 17%, and disciplinary action was taken in even fewer — 47, or 7% of the total. The LAFD has withheld the names of all but a handful of the firefighters whose disciplinary cases are addressed in this story. Open-government experts say the department’s refusal to disclose the names violates the California Public Records Act.

The documents that The Times managed to obtain reflect what critics say is a long-entrenched pattern of the LAFD failing to hold firefighters fully accountable for serious misconduct.

For example, since January 2018, the 3,400-member department has discharged just three firefighters, according to an LAFD spokesperson. The department did not release their names nor the specific circumstances of the dismissals. Two firings were noted in the LAFD’s quarterly disciplinary reports from January 2019 through the end of last year. Both were for the vaguely stated reason of “failure to meet conditions of employment.” One other firefighter during that period resigned during a Board of Rights hearing and another resigned “in lieu of termination,” the reports state.

In the same time frame, at least 16 firefighters were accused of either domestic violence, drunk driving or other criminal conduct, according to the available records.

The Times sought to examine additional years of disciplinary cases, but the quarterly reports from July 2016 through December 2018 were missing from the LAFD’s online archives. The department provided no explanation for why the records could not be found.

The LAFD also did not respond to queries about discrepancies in some of the records, including inconsistencies between the independent assessor’s report and the department’s quarterly summaries of disciplinary actions.

In recent years, The Times has documented cases in which high-ranking fire officials escaped discipline entirely. Then-Chief Deputy Fred Mathis was able to retire last year with a $1.4-million payout after a colleague reported that he appeared to be intoxicated while overseeing the agency’s operations center during the 2021 Palisades fire.

Results of an inquiry into a hit-and-run crash by an LAFD assistant chief show how discipline of any kind in the agency is uncommon — especially, critics say, for chief officers.

And the department waited more than two years before scheduling a Board of Rights hearing for Ellsworth Fortman, then an assistant chief, after he was involved in a hit-and-run crash, LAFD and law enforcement records show. A department investigation concluded Fortman, who was criminally charged in the crash, had been drinking before he smashed his truck into a parked car, propelling it 160 feet and toppling a street lamp, and fled the scene. In the two years after the incident, Fortman made $354,000 in overtime in addition to his annual salary of $221,500. He retired before any discipline was imposed.

Fire Chief Kristin Crowley declined to be interviewed for this story, and she did not answer a number of written questions about the disciplinary cases. Crowley became chief in March 2022 but was a member of the LAFD’s executive team for a half-dozen years and once headed the department’s Professional Standards Division, which investigates misconduct and recommends discipline.

A spokesperson for Mayor Karen Bass said in an email to The Times that she “has no tolerance for misconduct at the Los Angeles Fire Department or anywhere else especially when racism, sexual harassment and violence are involved. She expects — and the people of Los Angeles deserve — reform.”

Bass’ office did not respond to questions asking for specifics on such reforms. The mayor nominates the fire chief, whose appointment must be approved by the City Council. The fire commissioners are also selected by the mayor and approved by the council, and help set policy for the department.

On an April day last year, an LAFD captain noticed that a department cellphone was missing at Metro Fire Communications, as the downtown dispatch center is known. The phone was one of the older flip models available as a backup to firefighters in emergencies — and someone had been taking them from time to time without logging them out. The next day, the captain saw that the missing phone had been returned and needed to be charged.

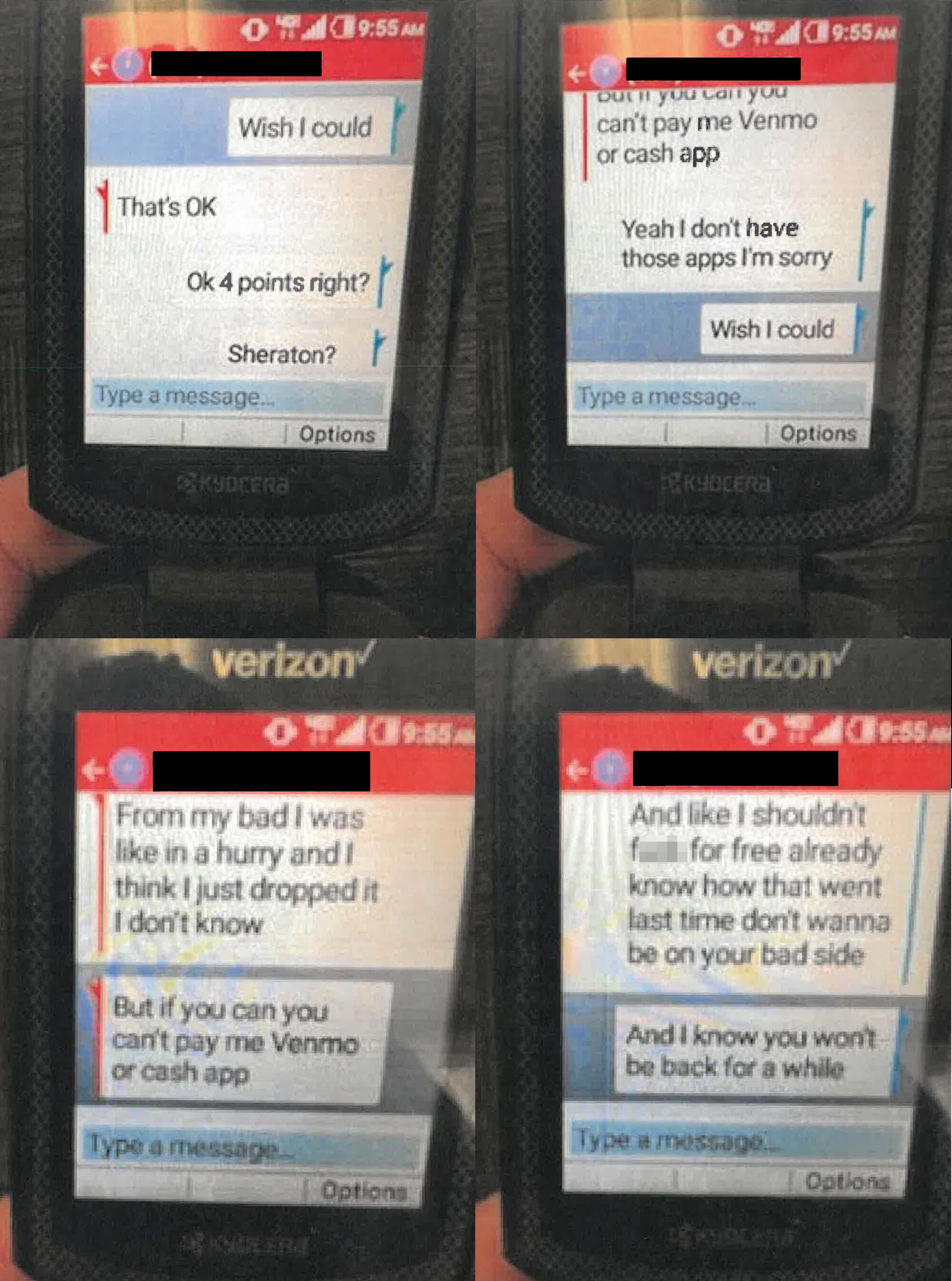

After charging it, he found a series of text messages in which Armando Gabaldon, a 15-year LAFD veteran, solicited sex from a prostitute at the Four Points by Sheraton near LAX, according to disciplinary records, which described the events as they unfolded.

“Gonna have to re schedule,” one text said, “went to the atm and f— ate my card only have 80 And like I shouldn’t f— for free already know how that went last time don’t wanna be on your bad side.”

The captain compared the times of the texts with images from a video camera filming the dispatch center parking lot. The camera captured Gabaldon driving out of the lot in his white pickup truck at 12:41 a.m., leaving his post without permission from his supervisor. He was seen in the video returning to the lot an hour to an hour and a half later. The captain informed his superiors and an internal investigation was launched.

Some days later, according to the LAFD records, Gabaldon approached another captain and said, “I want to come clean.” The captain told investigators that a crying Gabaldon had said, “I need help.”

In a subsequent interview with investigators, Gabaldon admitted that he used the phone to hire the prostitute and left his post without permission to meet her at the Sheraton. He said he had sex with her on four occasions but only once while he was on duty, and each time he paid her $100 to $150. Gabaldon said he was in treatment for sex addiction, a condition he attributed in part to post-traumatic stress disorder from an emergency call early in his career during which a year-old boy died.

Gabaldon was relieved of duty in October. In January, a Board of Rights made up of three LAFD battalion chiefs accepted his guilty plea to two administrative charges of using the department phone to solicit a prostitute and leaving his post. The board determined that his conduct violated three sections of the Fire Department’s rules and regulations.

“When you made a decision to engage in illicit sex while on duty,” the panel wrote in its findings, “you not only broke the law but you violated the trust of the department and most importantly the citizens of the city of Los Angeles.”

Although the panel could have fired Gabaldon, a majority of the board opted to suspend him without pay for six months. Among the reasons for the lesser punishment were his admission of guilt, his years of satisfactory performance, his psychologist’s comments about his condition and his “working countless days in a row” at the dispatch center. (Gabaldon was well-compensated for those days; his gross pay last year was $291,500, according to the LAFD.)

But one of the board members, Battalion Chief Timothy Lambert, disagreed that Gabaldon should not be fired. Lambert wrote in a statement of dissent that he questioned the sincerity of Gabaldon’s testimony and “was skeptical that he would have made any of the life changes he described had he not been caught. Mr. Gabaldon committed a crime, he did it while on duty, and he knowingly tried to hide his actions until they were discovered.”

In an interview with The Times, Gabaldon said, “I regret everything I did,” but added that he should not have been fired. He echoed his statements to investigators in saying his conduct grew out of PTSD. Gabaldon said he had been reluctant to seek help because of his position as a firefighter.

“The helper doesn’t want to ask for help,” he said.

The LAFD reported Gabaldon’s admission of soliciting a prostitute to the Los Angeles Police Department for a possible criminal investigation. Gabaldon said he was not charged. An LAPD spokesperson said it had no record of an arrest of Gabaldon, and the L.A. city attorney’s office confirmed that it had received no request from the LAPD to prosecute him.

The Times asked Crowley if she agreed with the decision not to fire Gabaldon. As she did in response to several other questions for this story, Crowley replied in writing through a spokesperson and did not provide a direct answer. “Chief Crowley agreed that the Board [of Rights] determines Firefighter Gabaldon’s duty status,” the spokesperson wrote.

Woods-Gray, the fire commissioner, said Gabaldon’s case underscored the need to replace the Board of Rights system with an independent disciplinary body, such as a panel of retired judges. She said Boards of Rights amount to self-policing by firefighters as if they were “one big family,” which inevitably breeds leniency against wrongdoers.

And she said that the commission has virtually no say in the LAFD’s disciplinary actions. The agency “kind of runs itself,” Woods-Gray said. “The department has no real discipline policy. It’s subjective.”

Of the 112 cases in 2021 in which the LAFD determined there was evidence supporting a complaint, the department decided punishment was not warranted in 65. Among them:

- An internal complaint alleged that two firefighters, one of them a captain, made racist comments in a phone call, including, “Candidates should try a different department, and it’s too bad, we’re not hiring Mexicans right now. … Oh, I guess the candidates have to be black faces and paint their face black to pass the interview.” An inquiry sustained the allegation, but no punishment was imposed. The captain is Filipino and the firefighter is Latino, a department spokesperson said. In statements to The Times, the LAFD said it determined “the facts of the case did not support a punitive resolution” because “it was a first-time occurrence, made by an off-duty member during a private conversation.” The department said one of the firefighters “received counseling and training from his supervisor.”

- In a social media post, a white firefighter wrote, “SAY HER NAME … DRUG DEALER,” in an apparent reference to Breonna Taylor, the 26-year-old Black medical worker who was shot to death by Louisville police officers in a botched 2020 drug raid on her apartment. Four current and former officers were charged last year with federal crimes, including civil rights violations in connection with the shooting, and one pleaded guilty. In an email to The Times, the LAFD stated, “The social media post was determined to be protected speech under the U.S. Constitution.”

- Twelve men in swimsuits at a lake or river posed for an Instagram post with a Trump 2020 banner and a caption that read in part, “Proud Boy Fire Department #wattstowers #Firestation64 #lafd #Watts.” Civil rights organizations have labeled the Proud Boys a hate group whose members often espouse white nationalist views. A Washington, D.C., jury Thursday convicted four Proud Boys members on seditious conspiracy charges for their role in the Jan. 6, 2021, assault on the U.S. Capitol. The LAFD told The Times that the post was also protected speech under the Constitution.

Woods-Gray, until recently the only one of the five members of the commission to respond to Times queries about LAFD misconduct, said that “something needs to be done” about firefighters who make racist remarks and that she was “livid” about the Proud Boys post.

“Firefighters represent the Fire Department wherever they are, whether they are on duty or off duty,” Woods-Gray said.

A new commissioner, Sharon Delugach, who joined the panel last month, said she planned to get up to speed on the complaints about the disciplinary process. “I’m interested in digging into this,” Delugach said.

“Firefighters represent the Fire Department wherever they are, whether they are on duty or off duty,”

— Jimmie Woods-Gray, president of the Fire Commission

Woods-Gray and other critics of the disciplinary system largely blame the influence that the Fire Department’s two unions have over the city’s elected officials and the department’s leadership. The critics say the unions use the clout that comes from their election endorsements and campaign contributions to thwart reforms.

Andrew Glazier, who advocated for fair treatment of women and nonwhite firefighters during eight years on the Fire Commission, said the unions have local politicians “wrapped around their finger.”

“You’re fighting the unions,” Glazier said of prospective changes in the policies. “They’re not the only problem, but they’re part of the problem.” He said another roadblock to reform is bureaucratic bungling within the Professional Standards Division.

Glazier contended that then-Mayor Eric Garcetti did not reappoint him to the panel in 2021 because of complaints about him from the rank-and-file union, United Firefighters of Los Angeles City, which the labor organization’s president denied.

UFLAC and a union that represents Fire Department chief officers did not respond to Times requests for interviews or comment.

Erika Hall, an Emory University professor of organization and management who studies racial and gender biases on the job, said the actions of several firefighters in the LAFD cases would be “absolutely” fireable in a well-run organization.

“They sound pretty egregious,” she said.

Hall said that type of conduct has persisted in some fire and police agencies because of a “machismo” culture that breeds and tolerates racist and sexist behavior. “These workplace climates are extremely sticky because of the good ol’ boy network,” she added. “You have to take out the system. The entire system is built on keeping this culture alive.”

A racist and sexist culture within the LAFD has been a perennial source of complaints and calls for reform. Nearly 50 years ago, they led to a federal consent decree that forced the department to dramatically increase recruitment of people of color, who at the time accounted for just 5% of the firefighting force.

The court-enforced decree remained in place until 2002, when the number of nonwhite employees had reached 50%, but allegations of racial and sexual discrimination persisted. Five years after the decree was lifted, the city paid $1.5 million to settle a lawsuit by a Black firefighter who was fed dog food in a firehouse prank. And in 2021, six Black employees in the Fire Prevention Bureau, which is responsible for safety inspections and investigating the causes of fires, sued the city, alleging the LAFD favors white employees in granting promotions.

Despite repeated pledges by City Hall to boost recruitment of female firefighters, women still constitute only 3.4% of the force. The Times reported in 2021 that many female firefighters felt bullied and discriminated against. In August 2021, the U.S. Justice Department said it was “carefully reviewing” complaints by organizations representing female and nonwhite firefighters of discriminatory treatment in the LAFD, including in disciplinary cases. The federal agency has taken no public action since then.

The Times review of department records found there were seven cases in 2021 in which the department sustained domestic violence allegations against firefighters, up from one in the three previous years the independent assessor examined, combined. None of the firefighters has been fired, although as of last month two cases were awaiting a Board of Rights hearing, which could result in a firing or lesser punishment. Five of the firefighters received initial suspensions that ranged from eight to 26 days. Some suspensions were reduced to as few as two days because the firefighter took a counseling course, the records show.

The allegation against Fred Mathis erupted in a department beset with claims of preferential treatment for high-ranking officials and racial and gender discrimination in the ranks.

In May 2020, the wife of LAFD firefighter Brian Corntassel asked the Huntington Beach police to meet her near the couple’s home. She told the two officers who handled the call that she was moving out and that her husband had struck her on several occasions in the past. The officers spotted Corntassel driving up to the house at a high rate of speed, according to LAFD disciplinary records that detailed the department’s investigation. Corntassel, the records say, then parked his Ford Excursion, got out and yelled at the officers. The officers eventually confronted him, and he shoved one of them and resisted arrest. They subdued him with a neck hold that caused him to lose consciousness.

After his arrest, a blood test showed his alcohol level at 0.18% and 0.19%. One officer noted in an interview with an LAFD investigator that the test was performed several hours after Corntassel arrived in the Excursion, meaning the firefighter probably had been even more intoxicated than the result indicated.

The Orange County district attorney’s office charged Corntassel with five misdemeanors. He was arrested on suspicion of domestic violence, but the D.A. did not charge him with that. His wife later declined to speak to an LAFD investigator about the domestic violence allegations because the couple had “moved past those issues and they have sought counseling,” according to the LAFD disciplinary records.

Corntassel denied to LAFD investigators that he ever struck his wife or threatened to hit her. He further denied driving drunk; he said he started drinking after he parked the Excursion. In January, he pleaded guilty to battery on a police officer and alcohol-related reckless driving, court records show.

An LAFD investigation determined by a “preponderance” of the evidence that Corntassel, on separate occasions, slapped his wife on her feet and forearm, hit her with a pillow and threatened to punch her in the face, the disciplinary records show. Earlier in his career, Corntassel had been suspended three times for being absent without leave, hazing and failing to notify the LAFD that he had been arrested on suspicion of drunk driving, according to the records.

In the 2020 incident, the department suspended him for 26 days.

Crowley did not respond after The Times asked why Corntassel wasn’t fired.

Corntassel, 53, was found dead at his Huntington Beach home early last month. A determination of the cause of death is pending the results of toxicology tests, a spokesperson for the Orange County coroner’s office said.

Many of the 2021 cases involved allegations that firefighters violated medical protocols during emergency responses, including by failing to administer electrocardiograms to patients and falsifying records. In most of those cases, more than one firefighter was accused of the violation. Twelve of the cases resulted in reprimands and the others in suspensions that ranged from four to 16 days. Firefighters challenged many of the suspensions by requesting Board of Rights hearings that were pending at the time the assessor compiled the report last fall.

A veteran fire official with expertise in LAFD disciplinary procedures said medical protocol cases have often involved firefighters who refuse to treat homeless patients because the patients are unsanitary. In those cases, firefighters falsified medical records by stating the patient could not be found, said the official, who requested anonymity because he was not authorized to speak about the matter. He said these cases sometimes come to light because a patient later died or a lawsuit was filed against the city.

The Times asked the LAFD to identify any of the 2021 cases that grew out of allegations that firefighters violated protocols by declining to help homeless people. A department spokesperson replied: “The LAFD has no responsive documents pertaining to your additional inquiries.”

In another statement, the Fire Department sought to justify not releasing the names of all but a handful of the disciplined firefighters, saying that “a blanket release of the names … may violate a member’s privacy rights,” and that identities of firefighters in individual cases could be withheld after a “balancing of interests between an employee’s right to privacy and the public’s interest in disclosure.”

David Loy, legal director for the San Rafael-based First Amendment Coalition, said the LAFD’s refusal to release the names of all the firefighters accused in the 2021 cases is “absolutely an affront to transparency.”

“It’s an outrage,” he said. “These are public employees paid with public money to perform a public service.”

Loy said that without the names of the firefighters, it is impossible for the public to know whether the department handled the cases appropriately. “Was there bias?” he said. “Were they given a sweetheart deal?”

A third firefighter identified by the department for this story is former Capt. Paul Steele. (Last week, the LAFD partially identified two more firefighters.)

In December 2020, Steele was accompanying a three-person engine crew on a 911 call about a homeless man who was lying on a sidewalk, possibly unconscious. Two of the firefighters spoke to the man while Steele and the third crew member stood by. The man told the firefighters he was sleeping and did not need medical help. The firefighters said he had to sleep somewhere else so they wouldn’t get another 911 call about him.

Suddenly, Steele, with an agitated look on his face, said, “This is f— bulls—,” according to LAFD records documenting the internal investigation. He walked over to the man and yelled at him, “Get the f— up! Get the f— out of here!”

Steele then “purposely, deliberately, and forcefully kicked the patient right on the top of his head,” one of the firefighters is said to have told investigators. Dazed, the man scurried into nearby bushes and was not seen again.

All three crew members formally complained about the incident the next day. One said Steele’s kick was so hard that the man’s teeth could be heard clanking together. The blow was also described as a “big thump” and a “soccer kick.” When a crew member confronted Steele back at the fire station, saying his actions could bring consequences, Steele allegedly cut him off and said, “I looked around. I made sure there were no cameras before I did that,” according to the LAFD records.

In an interview with an LAFD investigator, Steele denied the account given by the crew members and accused them of lying to force him out of their station. He acknowledged that he was wrong to make any contact with the patient’s head, but he said he merely “tapped” him with his toe a couple of times, and the man’s head was cushioned by a blanket.

After he made contact with the man’s head, Steele told the investigator, Steele stepped back toward the engine and said to the firefighters: “Oh, s—. That wasn’t good. I knew I did wrong right there.”

Steele had a history of discipline, the department records show. He was previously suspended for leaving his assignment without securing relief, and he was reprimanded three times for violating various rules and for disrespectful behavior toward a colleague.

The department assigned Steele to his home — with pay — while the disciplinary process dragged on. It also reported him to the LAPD, and he was subsequently charged with misdemeanor battery, according to the LAFD records.

A spokesperson for Los Angeles City Atty. Hydee Feldstein Soto said the court has sealed all records in the Steele case under a state law that allows a defendant to ask that such records be kept under wraps if the defendant completes a diversion program. The spokesperson declined to release any more information.

Internal critics of the LAFD say the city attorney’s office has long gone easy on firefighters accused of misconduct, including by stalling investigations of serious wrongdoing by farming them out to private law firms. Feldstein Soto, who was elected in November, had her swearing-in ceremony at the LAFD’s training center, with UFLAC President Freddy Escobar serving as emcee.

In a statement to The Times, Feldstein Soto said: “Before my election as city attorney, I publicly called for reform within the LAFD after a series of alleged incidents of misconduct targeting women and Black firefighters came to light. I urged the chief, the firefighters’ union and the rank and file employees to work together to change the culture. To this date, my message has not changed.”

It was not until nine months after the Steele incident that the LAFD proposed a Board of Rights hearing for him. He retired before the hearing was held, thus escaping punishment. The Times was unable to reach Steele for comment. Upon retiring, he received a payout of about $120,000 in what the department described as unused leave and banked overtime.

Glazier, the former Fire Commission member, said the LAFD is facing the same disciplinary problems as it did when he joined the panel nearly a decade ago. He said he was disappointed but not surprised at the lack of progress, because the department remains afflicted with a deep-seated “culture of ‘boys will be boys.’”

“All I can do is shake my head at this point,” Glazier added.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.