‘Now we’re cooking with gas’ — and paying for it with massive bills

- Share via

Gas.

It won an Oscar for Ingrid Bergman in the movie “Gaslight,” and it delivered the punchline of a Daffy Duck cartoon.

At this moment, two companies are hoping to hoist the price of natural gas for 25 million Californians who are already gutting it out through a couple of smackdowns: a punishing winter, and the king’s-ransom gas heating bills to get through it.

Also on the rise: interest in research, like a Stanford study on gas stoves, reiterating the health and climate risks of a whole panoply of home gas-powered appliances — water heaters, furnaces, clothes dryers, and that soup-making, cookie-baking device, the gas stove.

Natural gas is a fossil fuel, just like the oil that’s refined into gasoline, and burning it can put out some of the same nasty, not-nice-for-humans crud. Most of what’s in natural gas is methane, which can explode in a confined space.

That bit of science was brought home to Angelenos in 1985, when methane gas in the basement of a Ross discount store near the Original Farmers Market blew up; 23 people were hurt. The city’s vast methane gas field extended to the spot near downtown chosen for a big school complex. It was 20 years of stop-and-start construction, destruction and mitigation for methane and earthquake risks before a school was finally built and opened there.

Get the latest from Patt Morrison

Los Angeles is a complex place. Luckily, there's someone who can provide context, history and culture.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

Even worse lay ahead. In 2015, gas escaping from the Aliso Canyon underground gas storage created perhaps the single most environmentally damaging natural gas leak in the nation’s history.

About 15% of the natural gas the nation uses goes into our houses, and the Census Bureau’s recent numbers are these: 61 million water heaters, 58 million furnaces, 20 million clothes dryers — and about 40 million home stoves.

All told, the greenhouse gases that these stoves can all expel amounts to as much as a half-a-million cars’ worth, which is approximately the number of cars on the road in front of you as you’re trying to get home early on a Friday.

In the Los Angeles metro area, the Census Bureau’s housing survey finds eight out of 10 of us are cooking with gas.

Does that phrase spark any memories? It should.

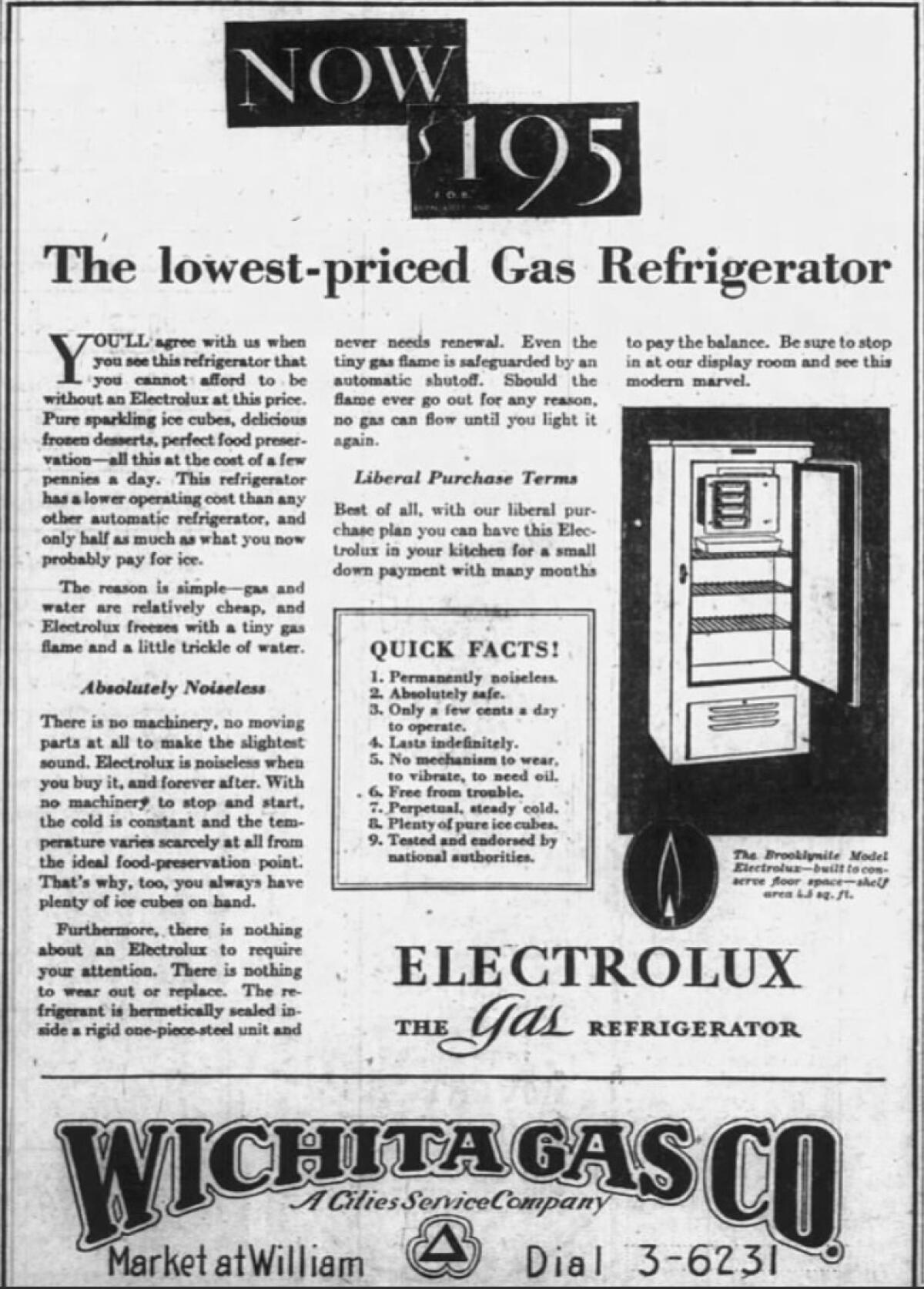

“Now you’re cooking with gas” is the ad-campaign phrase that launched millions of pilot lights. It helped to sell millions of indoor natural gas appliances, the oven foremost among them.

Deke Houlgate was a football publicist who devised the Houlgate system for deciding the national college football championship teams. He was also an exec with the American Gas Assn., and there, before World War II, he came up with the phrase.

He also knew some of comedian Bob Hope’s writers, and soon the “cooking” line was popping up in the repartee of Hope, the riffs of Jack Benny and that Looney Tunes cartoon. Eventually it morphed into a homefront catchphrase, meaning “Now you’ve got the idea,” or “Now you’re doing it right.”

I heard my grandparents say it; you may have heard yours do the same. In the 1960s, the glamor-puss actress Marlene Dietrich, who wore an apron as happily as she did a Travis Banton gown, wrote in a recipe book that “Every recipe I give is closely related to cooking with gas.”

The gas industry made sure to spread Dietrich’s endorsement. It was working hard to get Americans’ business for gas-equipped home appliances, versus the all-electric houses promoted by General Electric’s spokes-actor, Ronald Reagan.

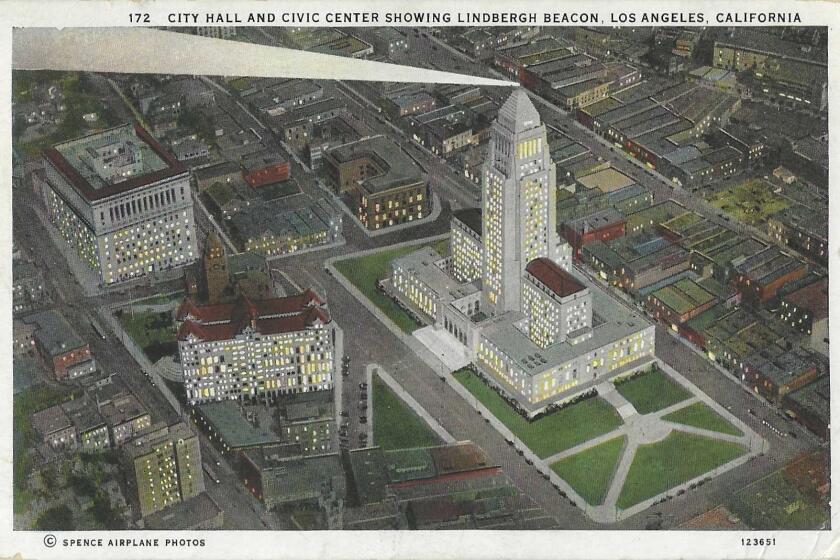

By the turn of the century, natural gas was already widely used for streetlights. Then, as it was being supplanted by the brighter glow of electricity, gas companies went looking for new markets, and built more and more reliable pipelines to supply them.

The gas had one almost serendipitous PR advantage: its name.

Anthony Leiserowitz is director of Yale University’s program on climate change communication. In the beginning, “natural” distinguished it from other gases, like coal gas, and signaled something that came straight out of the ground.

“It was originally not intended as a marketing thing,” he said, “but it is of course the term the industry has used for the past 130 years.” Recently, its “tremendous advantage as a marketing term is because that term ‘nature’ and ‘natural’ in the 1960s and ‘70s has come to develop a whole bunch of positive associations around it — almost like a halo.”

“You can see it at the grocery store: all the products they’re selling to you with the word ‘natural’ on them,” Leiserowitz said. “It’s not like ‘organic’ — there’s a strict definition and you have to adhere to certain standards there. But ‘natural’ is wide open.” And “in today’s America, we think of ‘natural’ as something that’s very good for you — even though,” he says with a smile in his voice, “arsenic is natural!”

You think this year’s rains were bad? The floods of 1938 were so epic they led to a massive re-engineering of the L.A. River that vastly reduced the ability to recharge groundwater.

Consumers already tend to conflate “organic” and “natural.” And, says Leiserowitz, “the industry is very happy to have this term because it distinguishes them from the other fossil fuels. We don’t think of natural gas as dirty and polluting as other fossil fuels. When you just call the gas what it is — methane — it’s interesting to see how associations change, [that] people have very different perceptions.”

Understandably, then, says Leiserowitz, natural gas manufacturers and promoters “don’t want you now to have a new association with your gas stove.” Natural gas appliances’ success is “very vulnerable to research that says actually burning methane in your kitchen is potentially harmful to your family.”

Natural gas’ image got a polish — a brief, kooky one — from the Trump administration in 2019. In a press release, the Energy Department called natural gas “freedom gas,” and praised the export of “molecules of U.S. freedom” to the world.

With potential health consequences on the front burner — yes, I wrote that — the stove is now the poster appliance for the industry’s campaign, and for some Republicans to take up the cry, “They’re coming for your gas stoves!” (Bumper-sticker version — they’re not. Though California and Los Angeles are phasing out new gas hookups.) A dozen years ago, Americans heard something similar, the “They’re coming for your light bulbs!” political clamor against new lightbulb efficiency standards.

Rebecca Leber is a climate journalist at Vox, and before that at Mother Jones magazine. She’s written frequently about the gas industry’s 21st-century advertising campaign, which runs well beyond Bob Hope “cooking with gas” jokes and an indisputably corny 1988 four-minute-long “rap” video extolling gas cooking, with safety tips.

Now, says Leber, social media influencers — like chefs and supposedly regular folks — post personal testimonials. The subtext, says Leber, is “how vital the gas stove is to an industry that otherwise doesn’t have products that Americans really care for the way they’re passionate about the gas stove.”

Four decades ago, the Consumer Product Safety Commission and the EPA were considering regulations on indoor air pollution risks and the gizmos that created them. “There was a lot of pushback,” Leber found. “The headlines at the time sounded so familiar to what we’ve seen in the last months.”

Today’s PR campaign has a more nuanced mission than selling appliances. Leber thinks that, above and beyond improvements in gas stove venting (not always available to renters and people in older buildings) a meta-message invoking a stove’s apple-pie presence in a home “can be used to drive a wedge to fight climate initiatives around the country, [where] climate-change climate activists push for cities and states to phase out gas in new buildings.” The gas industry, she is convinced, is campaigning mightily because it worries about losing new markets, and losing the market share it already has to climate-change and antipollution rules.

People generally “don’t feel that strongly about what is heating their homes or making their water hot, as long as it works. But “using the stove to trigger this emotional response, to capture the popular imagination.”

Whatever ad techniques get deployed, don’t count on a revival of anything like that 1988 hip-hop number, where dancing young people wearing Jiffy Pop chef hats assure you in song that “Natural gas is fun! Natural gas is clean!”

Los Angeles is a big, complicated place. Patt Morrison explaining how it works, its history and its culture in Explaining L.A. Tuesdays on latimes.com.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.