Years of bad blood, violence between warring families led to Goshen massacre that killed 6

- Share via

GOSHEN — The carnage on Harvest Avenue was so terrible — six family members from four generations executed in minutes — that the sheriff who responded to the scene could not fathom the killers had come from his world.

“This was not your run of the mill, low-end gang member,” Tulare County Sheriff Mike Boudreaux told reporters who descended that morning on Goshen, a poor community of about 5,000 that straddles the 99 freeway near Visalia.

A Mexican drug cartel, he said, was behind the massacre. The implication was clear: Tulare County has its share of gangs and drug dealers, but no one so pitiless as to execute a family that included a 16-year-old girl and her infant son could live among us.

But when the authorities arrested a pair of suspects 18 days later, they were not cartel assassins, but local gang members. Their work was not a professional hit, it now appears, but the culmination of years of beefs and simmering bad blood between two families who lived and hated one another on the same desolate patch of land.

The feud between the Parraz family, six of whom were slain the morning of Jan. 16, and the Anallas, to whom one of the suspects is related, began when a Parraz shot up the Analla matriarch’s home many years ago, a member of the Analla family said.

In a twist, the two clans are entangled by romantic ties. One of the victims at the Parraz house was an Analla.

Over the years, at least three members of the Analla family were sent to prison for attacking the Parrazes. Their mutual hatred would spill over into a shooting at a trailer park, a beatdown in a dirt lot, a woman threatening a grandmother with a baseball bat, and finally, Jordan shoeprints in the mud and gunfire in the dark.

*

John Tabares was angry. Too angry, he told a Times reporter, to talk.

Then, in fits and starts, he began talking about his brother, Angel Uriarte, a member of the Analla family and one of the two men accused of committing the massacre.

He talked of how, when his brother came home from prison in 2021, he and his mother tried to get him to hold down a job, to take classes for his anger, which he’d never been able to control. He recalled how they pleaded with him to leave behind the old crowd that had sent him down the wrong path.

When he was a student at Mt. Whitney High School in Visalia, one of Uriarte’s friends joined a gang, Tabares said. The friend turned on Uriarte and began bullying him, so Uriarte started hanging around Norteños — rivals of the Sureño gang his friend had joined.

Gangs that identify as Sureño answer to the Mexican Mafia, a prison-based organization whose members are drawn from Southern California gangs. They wear blue and append the number “13” — M being the 13th letter of the alphabet — to the names of their gangs. Norteño gangs favor red and follow the Nuestra Familia, a rival prison syndicate.

For many years, the line dividing California between Sureño and Norteño, blue and red, was drawn at Bakersfield. But Mexican Mafia members have begun pushing crews into Central and Northern California, where drugs command higher prices than in Southern California markets crowded with competing dealers, according to an FBI report reviewed by The Times. Gangs in once solidly red neighborhoods are now identifying as Sureños, raising tensions on the streets.

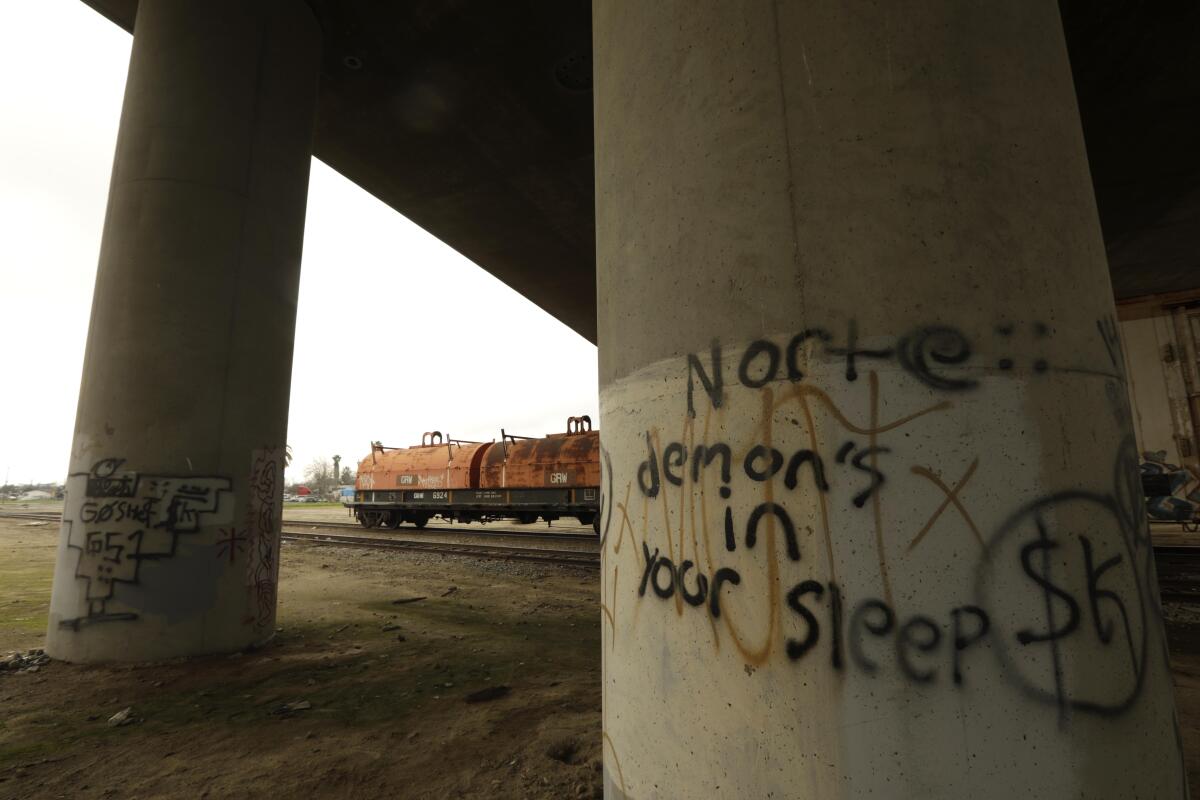

The Parrazes are Sureños, while the Anallas identify as Norteños, according to court records. Both families live in the same corner of Goshen, wedged between an industrial site and the 99 and bisected by railroad tracks.

Many of the homes — rundown stuccos and clapboards — are crowded by trailers and shacks built onto the properties. Forgotten cars, some stripped for parts, rust away in vacant lots. Dogs roam the streets and unpaved alleys.

According to Tabares, the feud began about a decade ago when Martin Parraz shot up the house of their grandmother, who lives across the railroad tracks from the Parraz home, a fenced-off compound with two trailers and a shed in the yard.

In retaliation, he said, his brother fired shots at the girlfriend of Martin’s uncle in a trailer park where the woman was staying.

A woman who drove Uriarte to the trailer park told deputies he’d said he had “funk” with the Parraz family, according to a police report. Another woman who was in the car told deputies the Parrazes “got what they deserve.”

Uriarte, then 26, was charged with assault with a gun. At the time of his arrest, he reported living a block from the Parraz house in a dilapidated, pink stucco home with his five children, fiancée and soon to be mother-in-law.

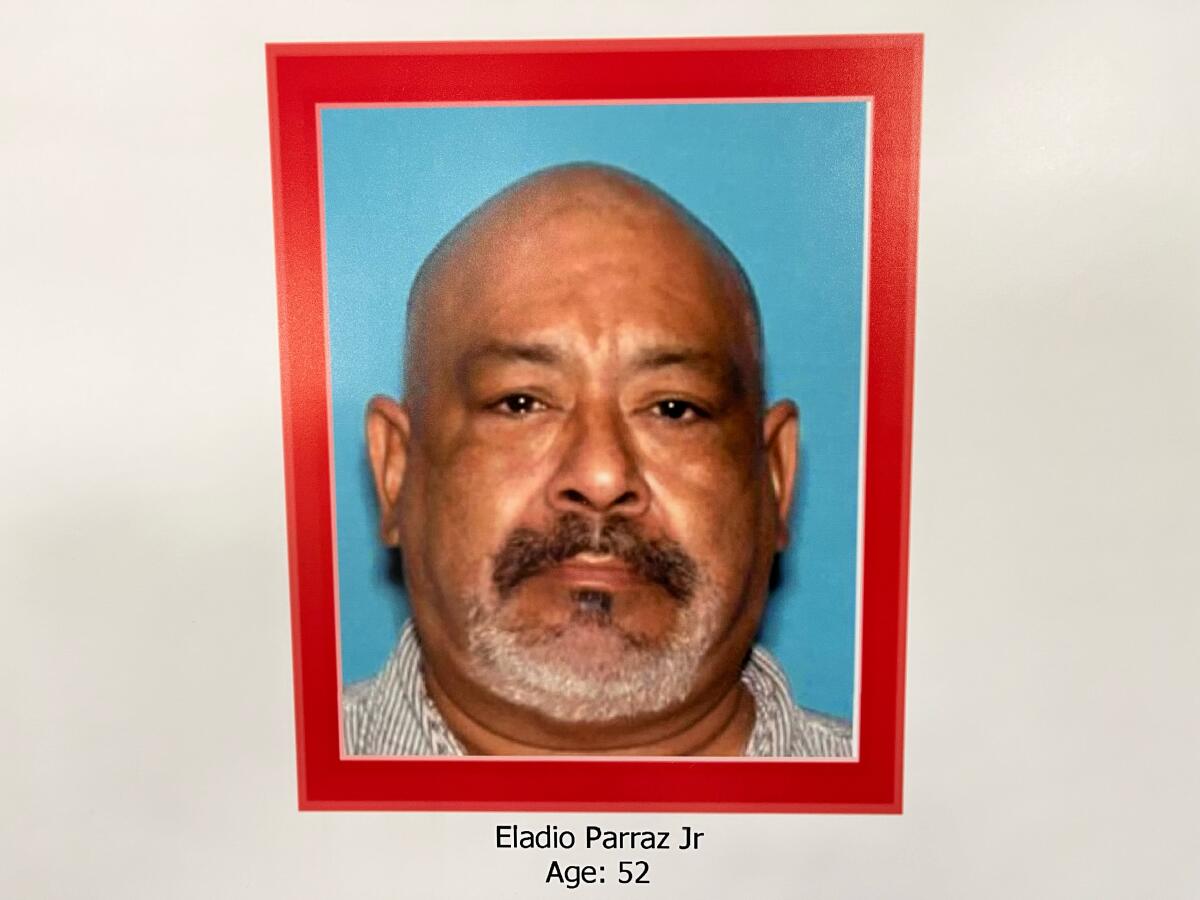

The night of the shooting, Martin Parraz’s uncle, Eladio, had told deputies about the feud between his family and Uriarte, who he immediately suspected was behind it.

But when called to testify against him a few months later, Eladio Parraz claimed not to know anything. “Something happened,” he said. “I don’t know. I wasn’t there.”

Parraz said he didn’t know anyone who went by Uriarte’s nickname — “Nano” or “Nanu” — but then relented somewhat. “I know his whole family. I know of him. I know his family.”

A Tulare County gang detective testified there was bad blood between the Parraz and Analla families, but did not elaborate.

Uriarte pleaded no contest in the case, admitted a gang enhancement and was sentenced to seven years in prison.

Tabares described his brother as erratic and prone to rage, but also impressionable — a follower who listened to people who “filled his head with lies.”

“He doesn’t understand that this doesn’t just affect him,” Tabares said. “This affects all of us.”

*

Seven months after the shooting in the trailer park, sheriff’s deputies were called to the Parraz home by a woman who said she’d been assaulted by four “Northern” gang members.

Crystal Parraz told the deputies she’d been walking with her young sons and 15-year-old cousin, Angel Castro, when some people in a silver car started harassing them. They yelled “Scraps” — a derogatory term for a Sureño — at Castro, a deputy wrote in a report.

The car stopped and four men got out. Parraz told her cousin to run.

Parraz said she recognized two of them: Andrew Analla, 21, and his cousin, Paul Romo, 19. Both lived around the corner, the deputy wrote.

Analla and Romo chased Castro across a dirt lot. They caught up to him, knocking him to the ground and kicking him in the head and the ribs, Parraz said. Castro struggled to his feet and ran toward his house.

One of the men she didn’t know drew a gun and aimed it at her cousin, Parraz said. The man, who had a dollar sign tattooed on his left cheek, didn’t pull the trigger and put the gun back in his waistband, she told deputies.

Parraz said Analla’s sister, Mona Lisa Analla, showed up to her home on Harvest Avenue, “yelling at her and trying to entice her into a fight,” the deputy wrote. Analla’s grandmother, Margie, joined in, Parraz said, challenging her to come out into the street. Parraz admitted walking out onto her driveway with a baseball bat.

Deputies found Andrew Analla standing in the frontyard of the same pink house on Avenue 306 that Uriarte had called home, according to police records.

His sister, who was there too, told deputies that Crystal Parraz had started the confrontation by “talking sh—.” Mona Lisa Analla said she heard someone say from behind the Parrazes’ security door: “Get the f— out of here before I shoot you.”

Deputies then went around the corner to Romo’s house and spoke with his mother, who said Eladio Parraz had ratcheted up tensions by cruising past the young men in his motor home.

“Both sides just looked at each other,” she said, “mean-mugging.”

Analla and Romo pleaded no contest to assaulting Castro and admitted gang affiliations, court records show. Both were sentenced to nine years in prison.

*

On Jan. 3, four sheriff’s deputies went to the Parraz compound for a parole check on Martin Parraz, who had done five years in prison for beating another inmate in the Tulare County jail.

Two trailers were on the Parraz property, a deputy wrote in a report. Eladio Parraz said he lived in one, while Martin Parraz lived in the other.

In Eladio Parraz’s trailer, deputies found methamphetamine, pipes and a bulletproof vest, the deputy wrote. Hidden beneath a mattress was an assault rifle, shotgun and handgun, the report says.

Charged with drugs and weapons violations, Eladio Parraz was released on $60,000 bail. Authorities also revoked Martin Parraz’s parole, finding he had access to ammunition found in a shed on the property, but did not take him into custody.

Thirteen days later, around 3:30 a.m., two men crept through an alley toward the Parraz home. Detectives would retrace their route using the impressions a pair of Jordan sneakers had left in the mud, Det. Jose Melendez wrote in a redacted affidavit reviewed by The Times.

The men turned left on Harvest Avenue and then continued onto Road 68, where they were captured on a surveillance system mounted to Eladio Parraz’s trailer. The pair jumped a fence onto a neighbor’s property, then walked toward the Parraz house, Melendez wrote.

Surveillance footage showed the two men walking up the driveway. One carried a short-barreled assault rifle. The other wore a trench coat and was armed with a handgun. Detectives concluded the person with the rifle was Noah Beard, 25. The man in the trench coat, they believe, was Uriarte.

Uriarte, now 35, had finished his prison term for the trailer park shooting in April 2021. Behind bars, he’d inked “GF” across his chest and a crude sketch of the Santa Muerte, its hands clasped in prayer, behind his right ear, photographs obtained by The Times show.

Eladio Parraz saw the men approaching on his surveillance system and was shot “moments after he stepped out of the trailer,” Melendez wrote.

His girlfriend, who was hiding inside the trailer, called 911.

“They shot my boyfriend. They keep shooting outside,” she told a dispatcher. “I don’t know if they are still here. I’m scared. ... Please hurry, please. I don’t know where they are now — [gasp] — they’re still shooting.”

“They’re still shooting?” the dispatcher asked.

“Yes,” she said. “Hurry please. They’re coming back. They’re coming back. They’re back.”

“Who’s coming back?”

“The guys. Do you hear them? Someone else is screaming now.”

After forcing open the front door to the Parraz home, Uriarte and Beard likely came across Marcos Parraz first, shooting the 19-year-old in the back of the head, Melendez wrote.

Jennifer Analla, 50, was killed in her sleep, Boudreaux said at a news conference. The sheriff said Analla was the girlfriend of a surviving member of the Parraz family.

Uriarte and Beard then tried to enter a bedroom whose door was locked, Melendez wrote. They tried another door and found Rosa Parraz, 72, kneeling beside her bed.

“We believe that she was getting out of her bed to check on what was happening,” Boudreaux said. “As the gunmen came in, she was on her knees and shot in the head.”

As shots and screams echoed through the home, Alissa Parraz grabbed her 10-month-old son, Nycholas, and ran down the driveway. The 16-year-old placed the baby on the other side of a fence and pulled herself over a nearby gate, surveillance footage showed.

Following the teenager down the driveway, Beard fired one or two shots at her, then climbed over the gate and shot both mother and child in the back of the head, according to Melendez’s affidavit and the sheriff’s statements.

Uriarte and Beard fled on foot, headed east across the railroad tracks, Melendez wrote.

Six days after the shooting, a Tulare County gang task force identified Uriarte as a suspect, noting he resembled the man in the trench coat captured by the Parrazes’ cameras, Melendez wrote. Uriarte “has a longtime family feud” with the victims, the detective wrote, noting his prior prison term for shooting at them in 2014.

An inmate, whose name is redacted in the affidavit, called his mother on a recorded jail phone and said “Angel” was in Goshen the night of the killings with “Ready,” whom the inmate described as mixed-race and wearing glasses, Melendez wrote.

Detectives believed “Ready” was Beard’s nickname. Beard, who has been convicted of car theft in Tulare County and robbery in Kansas, does not appear to have a connection to the Parraz family, according to a review of his court files.

Cell tower records placed Beard’s phone near the Parraz home at the time of the killings, Melendez wrote, while DNA collected from a live round left at the scene matched Uriarte’s.

Beard has pleaded not guilty to six counts of murder. Uriarte, who was shot in a gun battle with federal agents last week, is still recovering and has yet to enter a plea.

Boudreaux has said the killers were looking for someone who was not at the Parraz home that night. Melendez referenced in his affidavit a man who “occasionally stayed at the residence but hadn’t been there since Friday,” three days before the killings.

The man, whose name is redacted, “supposedly had a ‘hit’ on him when he was released from prison,” Melendez wrote.

Tabares believes his brother was looking for Martin Parraz. Four days before the killings, he said, someone shot at their grandmother’s home — the same offense that brought on the feud, all those years ago.

No one knew who fired the shots, Tabares said. But knowing his brother, Tabares said Uriarte would have assumed it was Martin Parraz, “because he’d done it before.”

“Anytime anything bad happened, he’d blame it on him,” Tabares said.

Martin Parraz, 47, has since been charged in federal court with possessing methamphetamine, heroin and a gun that a DEA agent said were found in his home and car when detectives came to interview him the day his relatives were slain.

Tabares said his mother was still grieving the loss of Jennifer Analla, who was her cousin, when she learned her son was a suspect. “When it came out on the news that he was arrested, she couldn’t get out of bed,” he said. “It destroyed her, that he would do this to family.”

Based on what he’s seen on the news, the footage of the men walking up the driveway, Tabares said he has no doubt his brother was one of the killers. He only hopes Uriarte will tell the police everything, including who else was involved. But knowing his brother, “he’ll take the rap for everything,” he said. “He’ll think that will make his friends like him more.”

“If it comes out that he killed the baby …” Tabares’ voice cracked. “That’s what everyone can’t understand. You don’t f—ing do that. You don’t do that to a baby, who’s innocent, who doesn’t have anything to do with that life. I don’t even know how he can ever start asking for forgiveness. I don’t even know.”

Times staff writer Ruben Vives contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.