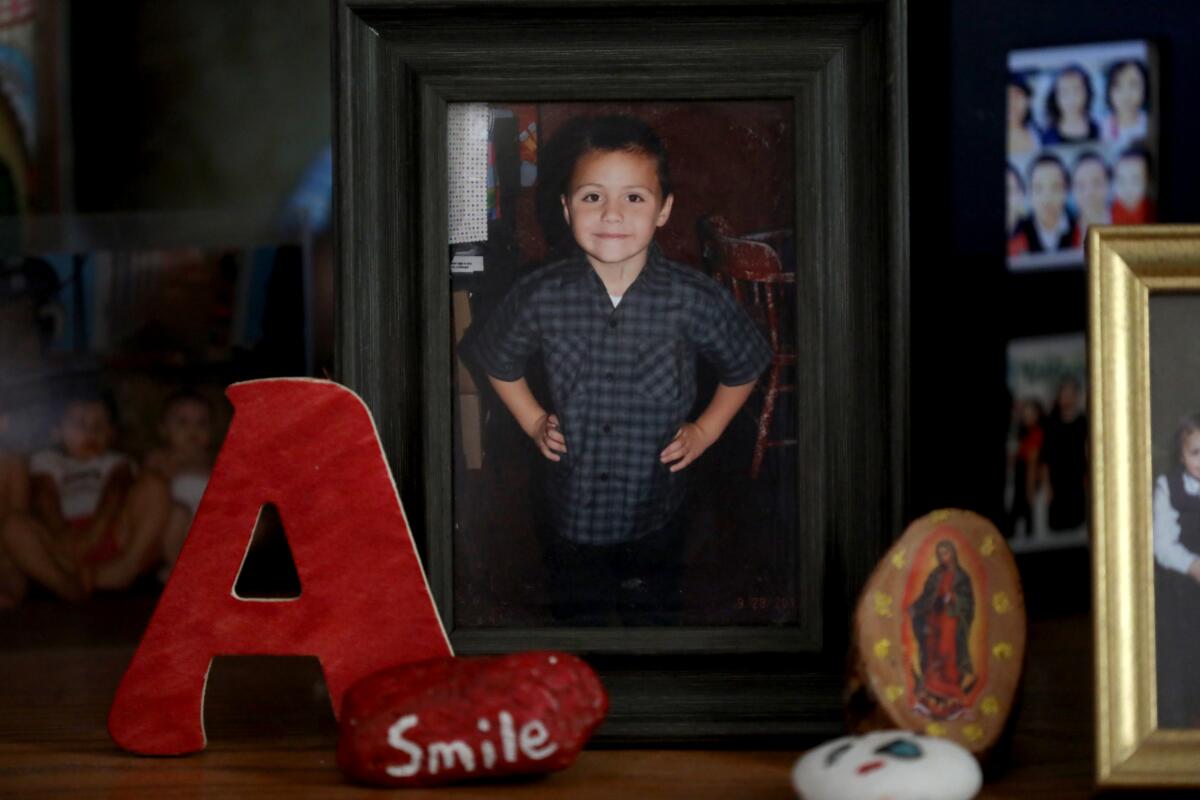

Years after abuse ended in Anthony Avalos’ death, his mother and her boyfriend go on trial

- Share via

The last four years of Anthony Avalos’ life were nearly constant torture.

The Antelope Valley boy would spend hours locked in a room with no access to food, water or a bathroom. His body was wracked with welts produced by the lashes of belts and electrical cables. Wounds on his knees would scab over and reopen after he was forced to kneel on uncooked rice and concrete. His blood dotted the room where he slept.

For the record:

9:06 p.m. Jan. 25, 2023A previous version of this article indicated the trial started Tuesday. It started Wednesday.

Anthony’s mother, Heather Barron, and her boyfriend, Kareem Leiva, sat stoically in a downtown Los Angeles courtroom Wednesday as prosecutors opened the trial against them by outlining the horrific abuse the couple is accused of inflicting on the boy, who ultimately died of head trauma in 2018. They have pleaded not guilty to torturing and murdering Anthony, and to abusing two of Barron’s other children. If convicted of all charges, they face life in prison.

At the time, Anthony’s death exposed the failure of Los Angeles County’s social services system to protect the 10-year-old and his siblings despite more than a dozen reports from relatives alleging Leiva and Barron were abusive. Now, the start of the trial four and half years later has turned the focus squarely on the tragedy of the boy’s short, pain-filled life and the people accused of ending it so violently.

“She’s been torturing her kids for a long period of time,” L.A. County Deputy Dist. Atty. Saeed Teymouri said of Barron on Wednesday. “Once defendant Leiva came into the picture, it turned deadly.”

Although Leiva admitted to severely abusing the boy in a recorded interview with Sheriff’s Department investigators that was played in court Wednesday, his attorney, Dan Chambers, argued that Leiva did not cause Anthony’s death and should be acquitted of his murder.

Barron’s attorney, Nancy Sperber, declined to give an opening statement. During the trial, Sperber is expected to try to shift blame onto Leiva. Barron has alleged in interviews with police that Leiva also abused her.

Instead of a jury trial, both defendants opted to have Los Angeles County Superior Court Judge Sam Ohta render a verdict in the case.

A 2019 Times investigation provided a timeline of Anthony’s devastating life. When he was 4 years old, his mother told relatives that her son had been sexually abused by a family member. Two years later, the boy’s aunt, Crystal Diuguid, told a therapist that Barron was beating Anthony and locking him in a room.

The reports of violence against the boy grew more severe. One day, he showed up to school with wounds believed to have been caused by BB gun pellets, according to The Times’ report. He told a vice principal that his mother’s abuse included forcing him to hold a squatted position for long periods of time with his arms outstretched, which she called “the captain’s chair.” A relative called an abuse hotline alleging that Leiva had dangled the children over a balcony and threatened to drop them, and sometimes picked Anthony up by his armpits before slamming him headfirst into the ground.

In the midst of the abuse, Anthony wrote a suicide note, according to records previously reviewed by The Times.

During his opening statement on Wednesday, Teymouri detailed a list of burns, cuts and malnutrition the boy suffered, and repeatedly displayed pictures of his battered body that were taken in the hospital before he died. Sobs escaped from the gallery every few minutes as relatives passed around a box of tissues.

Flipping between a picture of a younger, healthier and smiling Anthony and an image of the boy lying in a hospital bed with sunken, bloody eyes and a body covered in cuts and bruises, Teymouri looked at the defendants and said: “They turned this beautiful 10-year-old boy from this, to this.”

Anthony was brain-dead and had no pulse when paramedics arrived at his family’s Lancaster home in June 2018, according to Teymouri. Barron told paramedics the boy had thrown himself to the ground and hurt his head, but Teymouri said some of the other children in the house later told police he had been unconscious for nearly two days. In that time, Teymouri said, Leiva fled the home and signed over guardianship of his own five children to relatives, fearing he would be arrested.

At the trial, which is expected to last up to six weeks, multiple doctors and paramedics are expected to testify that Barron did not look bothered, and at other times appeared to be feigning tears, while her son lay unconscious and dying. Other witnesses are expected to paint Leiva as a violent gang member who starved and beat the children whenever they were out of Barron’s sight.

In addition to determining the defendants’ guilt or innocence, the trial will also serve as a referendum on the county’s Department of Children and Family Services.

Barron’s sister-in-law, Maria Barron, took the stand Wednesday and wept after prosecutors replayed a call her husband had made to a county hotline in 2015, detailing abuse Anthony and the other children allegedly suffered from Leiva. After the report was filed, Maria Barron said, the agency allowed her sister-in-law to have an unsupervised visit with the children, during which she recorded them recanting the abuse allegations. The agency’s caseworkers later returned the children to Leiva and Barron, who cut off contact with her sister-in-law.

“We weren’t allowed to see the kids anymore … we couldn’t save them,” Maria Barron said.

It was the first of many failures. The agency, which was monitoring Anthony for most of a four-year period from 2013 to 2017, received at least 13 reports about him in that time from relatives, teachers, counselors and police, yet the boy remained in Leiva and Barron’s home. No DCFS employees have been disciplined in connection with the case, the agency has said.

Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department Det. Chris Wyatt also took a report that alleged Leiva had abused another one of Barron’s children. Wyatt saw wounds on the child’s ear, but made no attempt to find Leiva or pursue an investigation, according to the detective’s grand jury testimony. Despite investigating the family for three years, DCFS workers never interviewed Leiva, according to case notes previously reviewed by The Times.

The case has often drawn comparisons to the torture and murder of 8-year-old Gabriel Fernandez, whose case also highlighted major flaws within DCFS. Prosecutors attempted to charge four social workers for failing to properly report the abuse suffered by Gabriel, but an appellate court threw the case out.

Prosecutors did not try to bring charges against DCFS employees in Anthony’s death, though counselor Barbara Dixon was placed on probation by a state board for failing to report suspected abuse of both boys before their deaths.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.