- Share via

From many cultures of the Mideast and beyond, we get the useful saying that “The dogs bark, but the caravan moves on.”

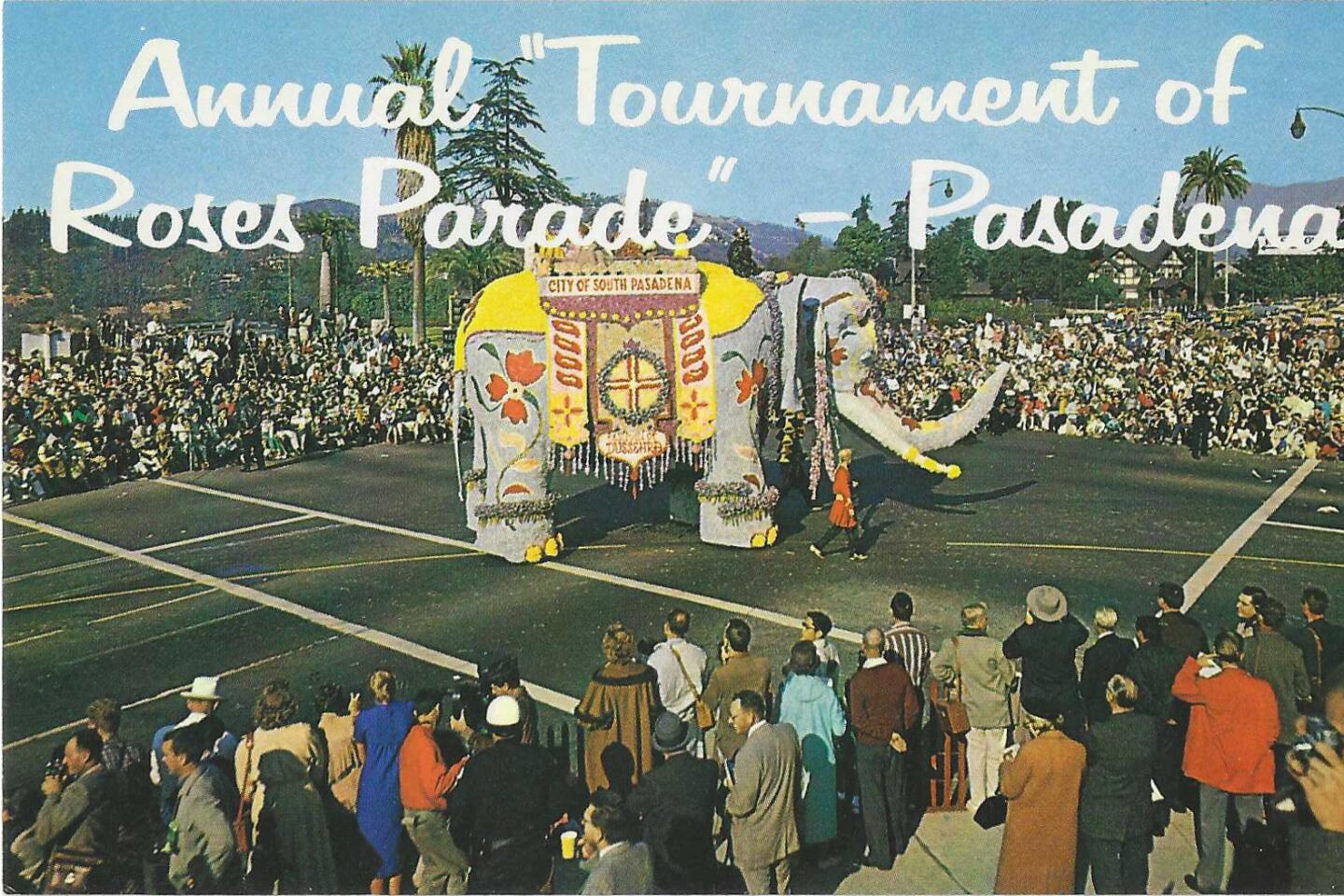

That’s the Tournament of Roses parade for you. It’s been the culture’s bull’s-eye for being too white, too male, too conservative — but still, it rolls on.

By this time next week, Pasadena will be sweeping up the blossoms and the trash dropped along the 5.5 miles of what’s officially counted as the 134th Rose Parade, even though there were four years when the dogs of war and of COVID-19 barked, and the caravan did not move at all: 1942, right after the Pearl Harbor attack, in 1943, in 1945, and again in 2021.

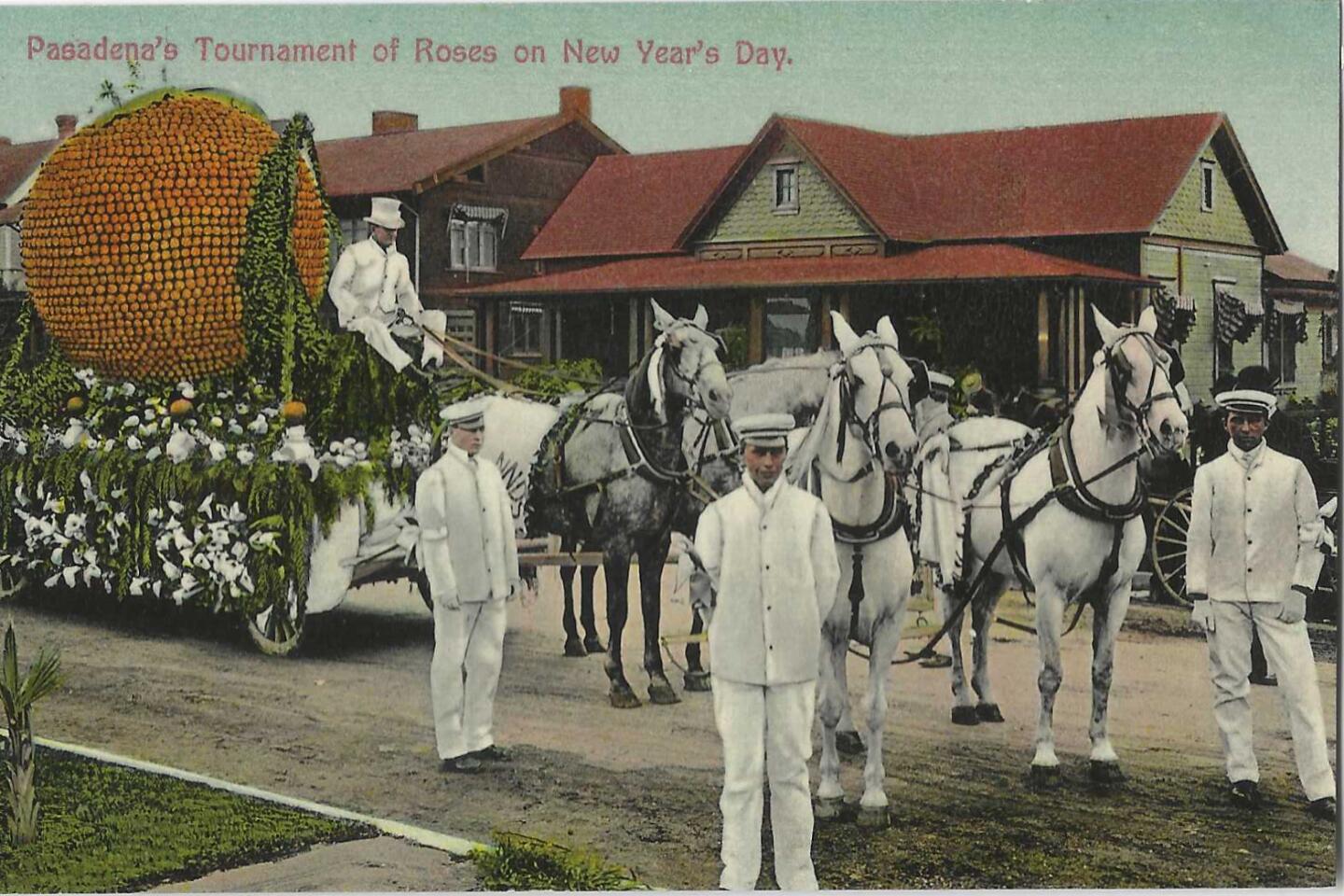

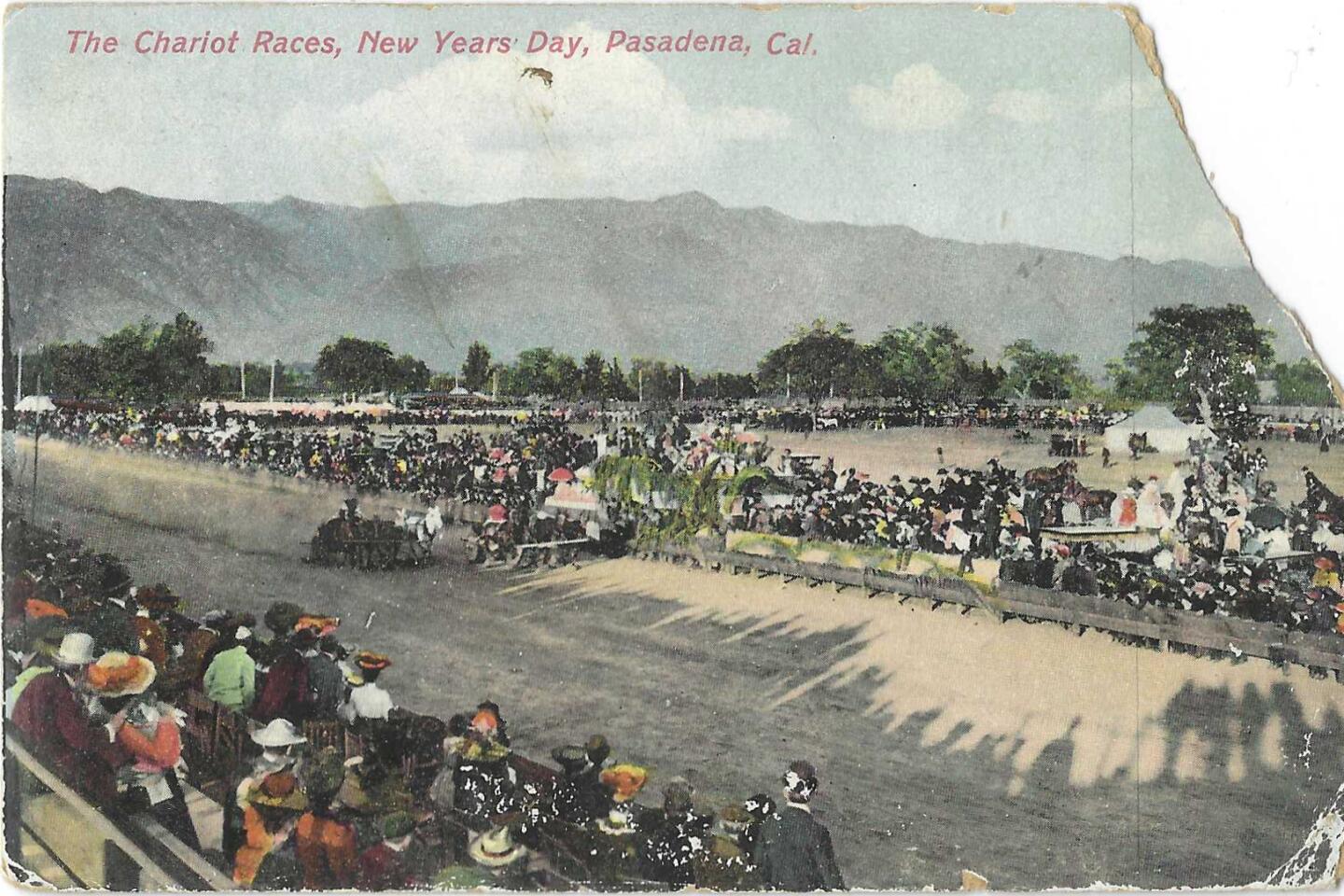

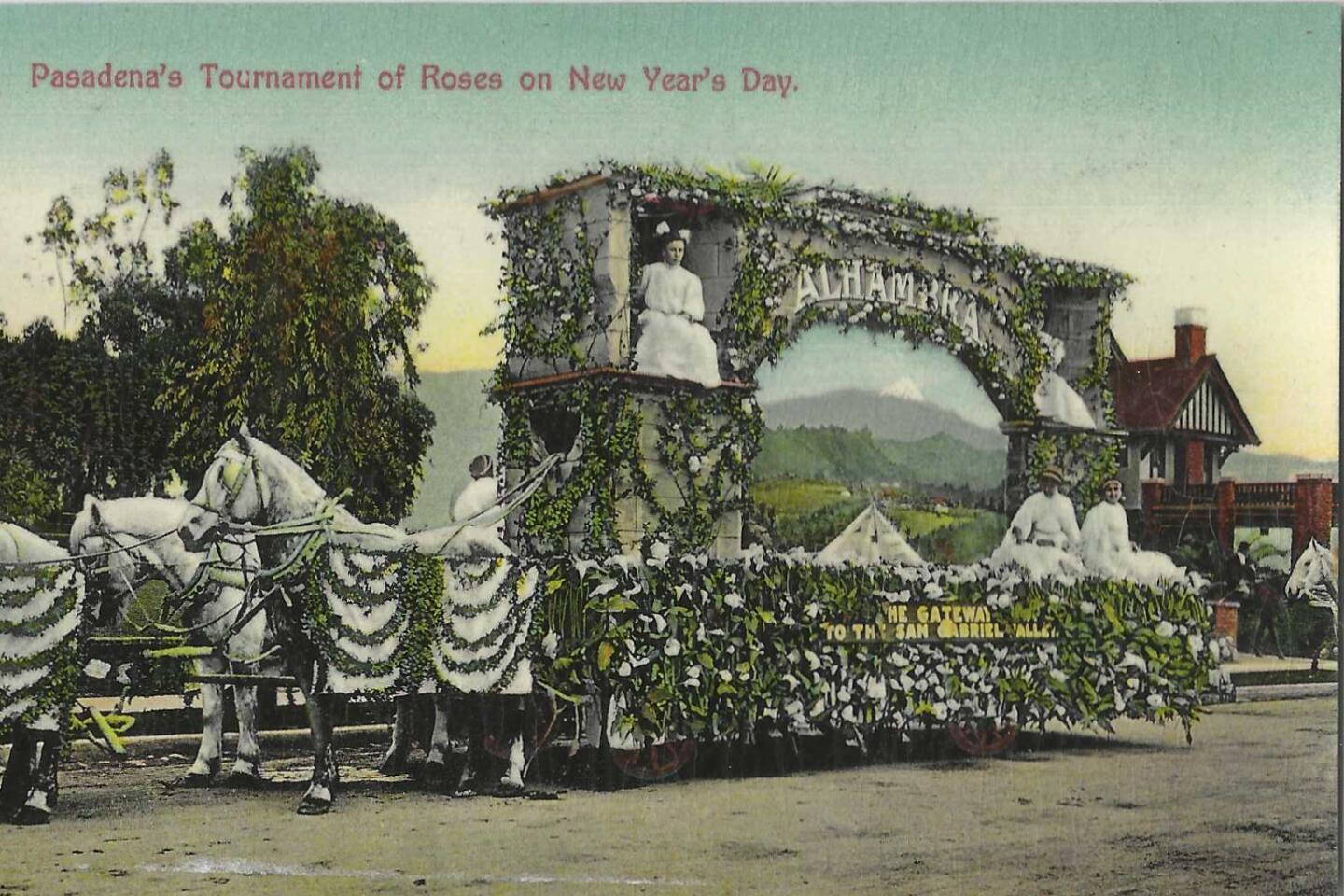

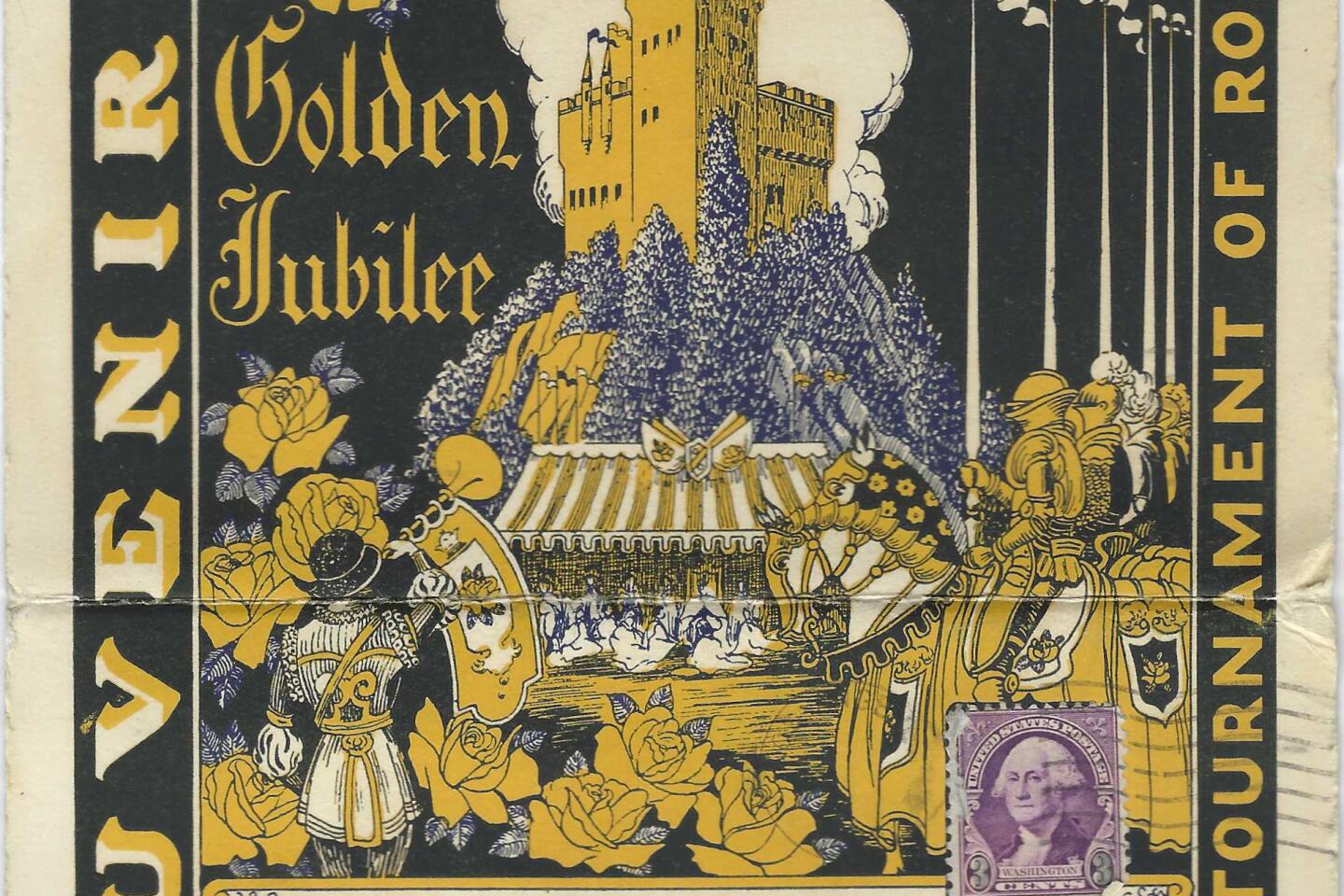

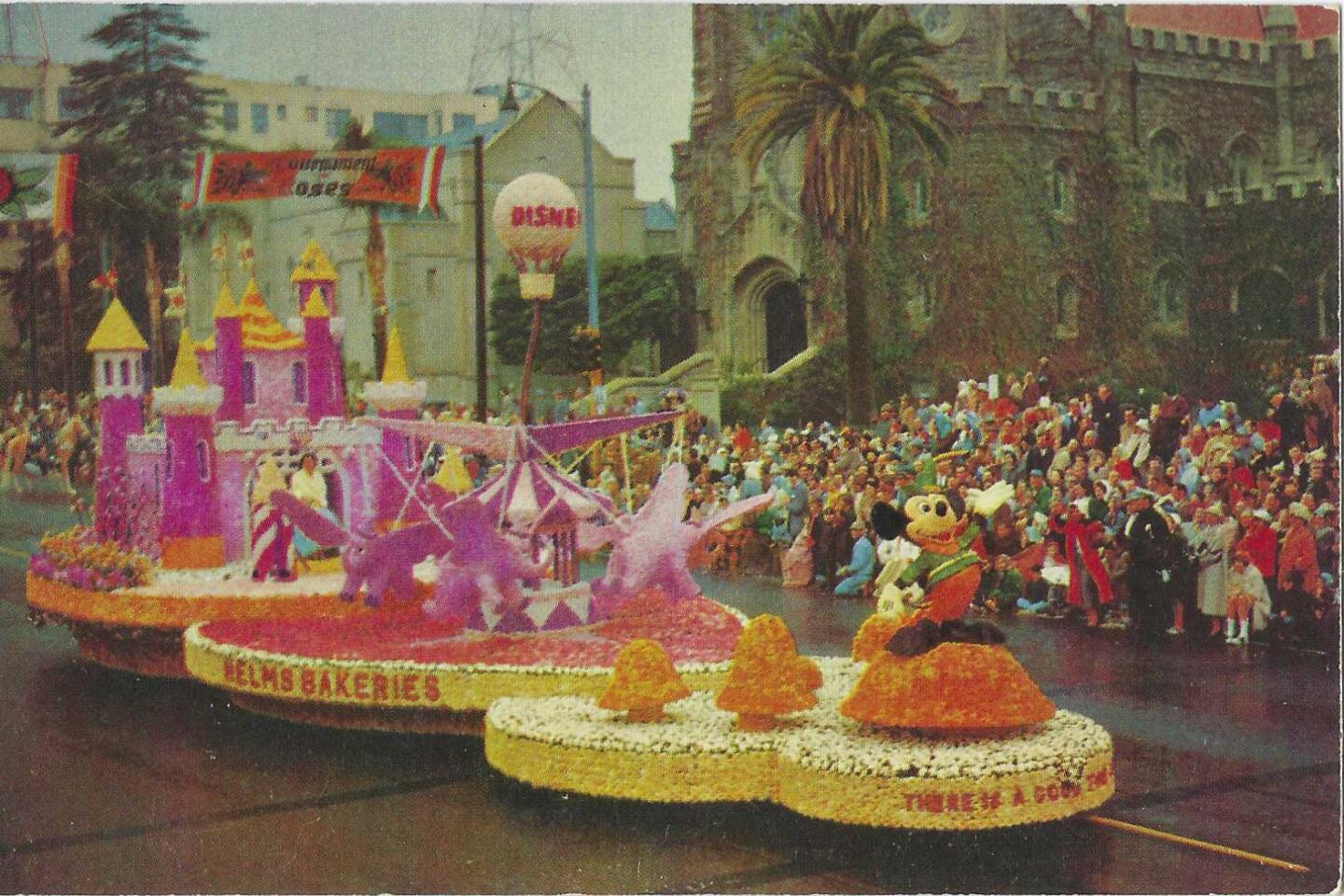

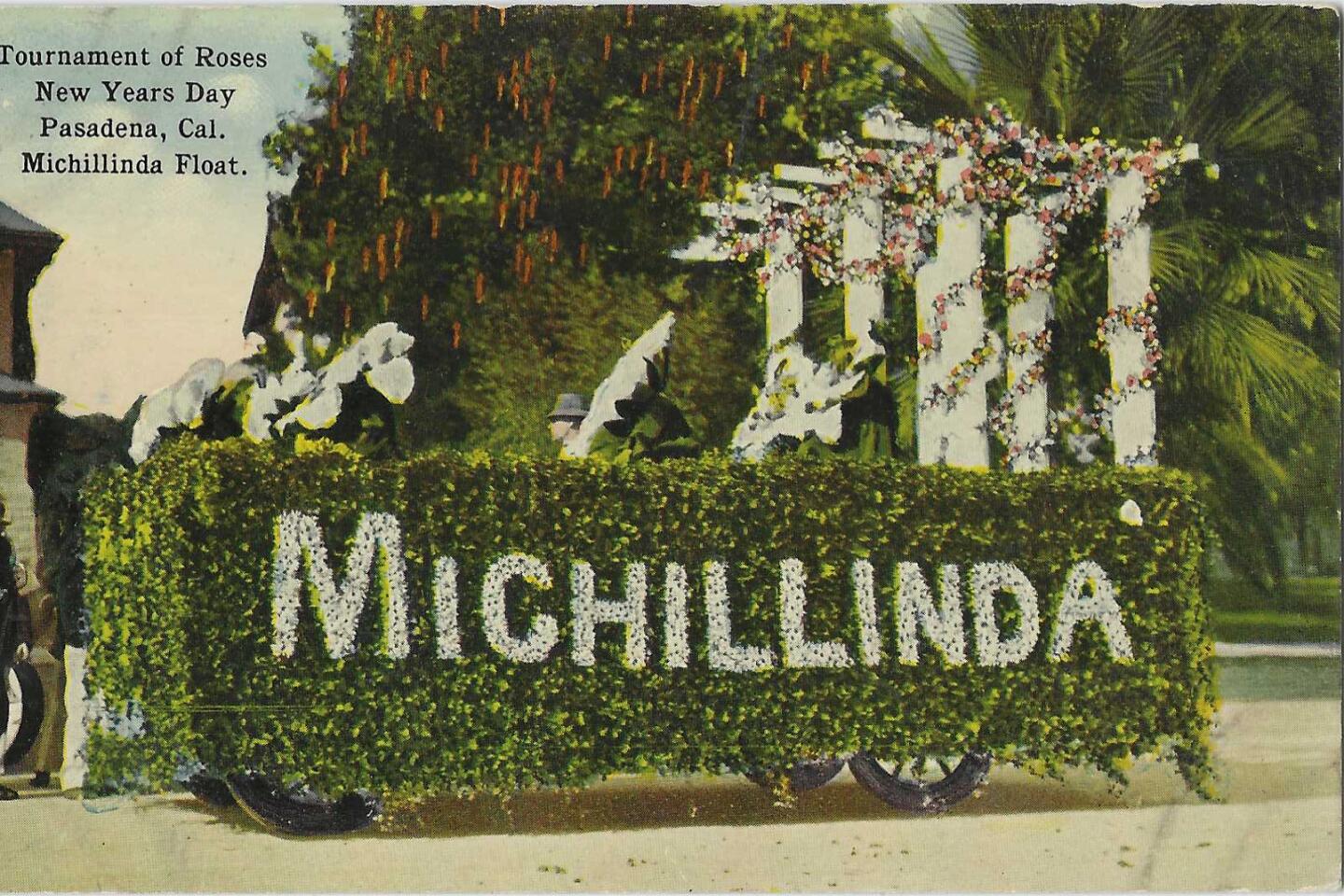

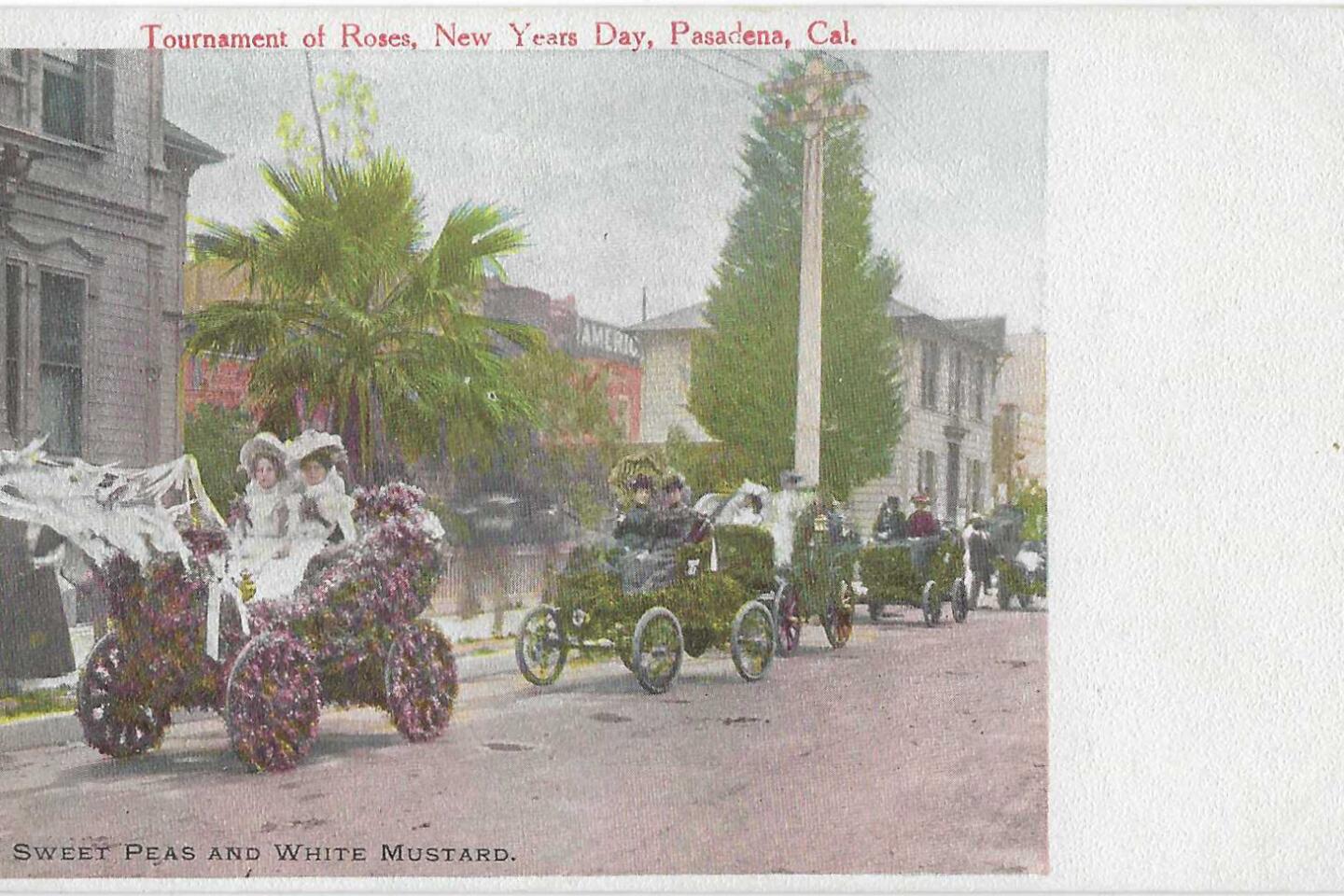

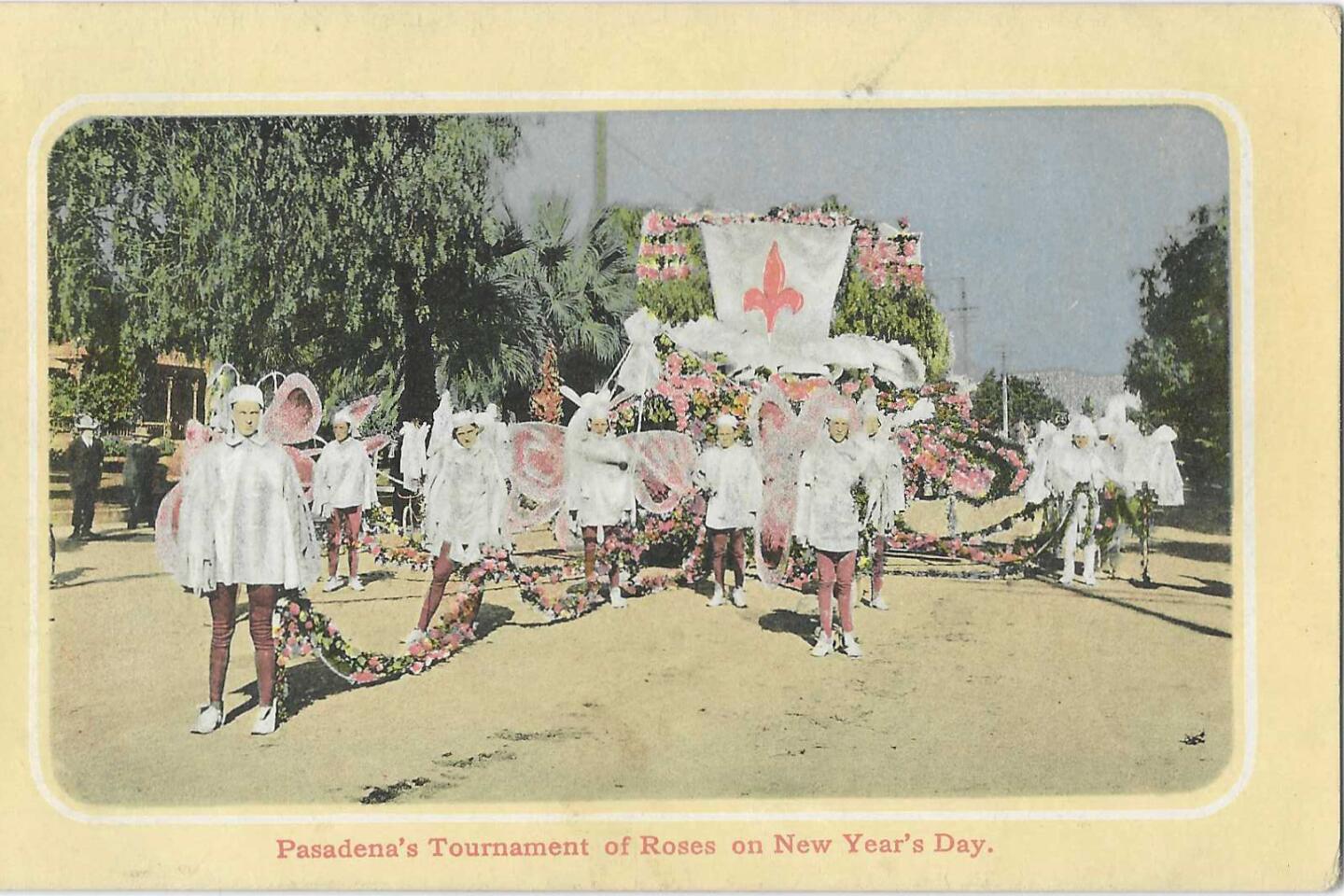

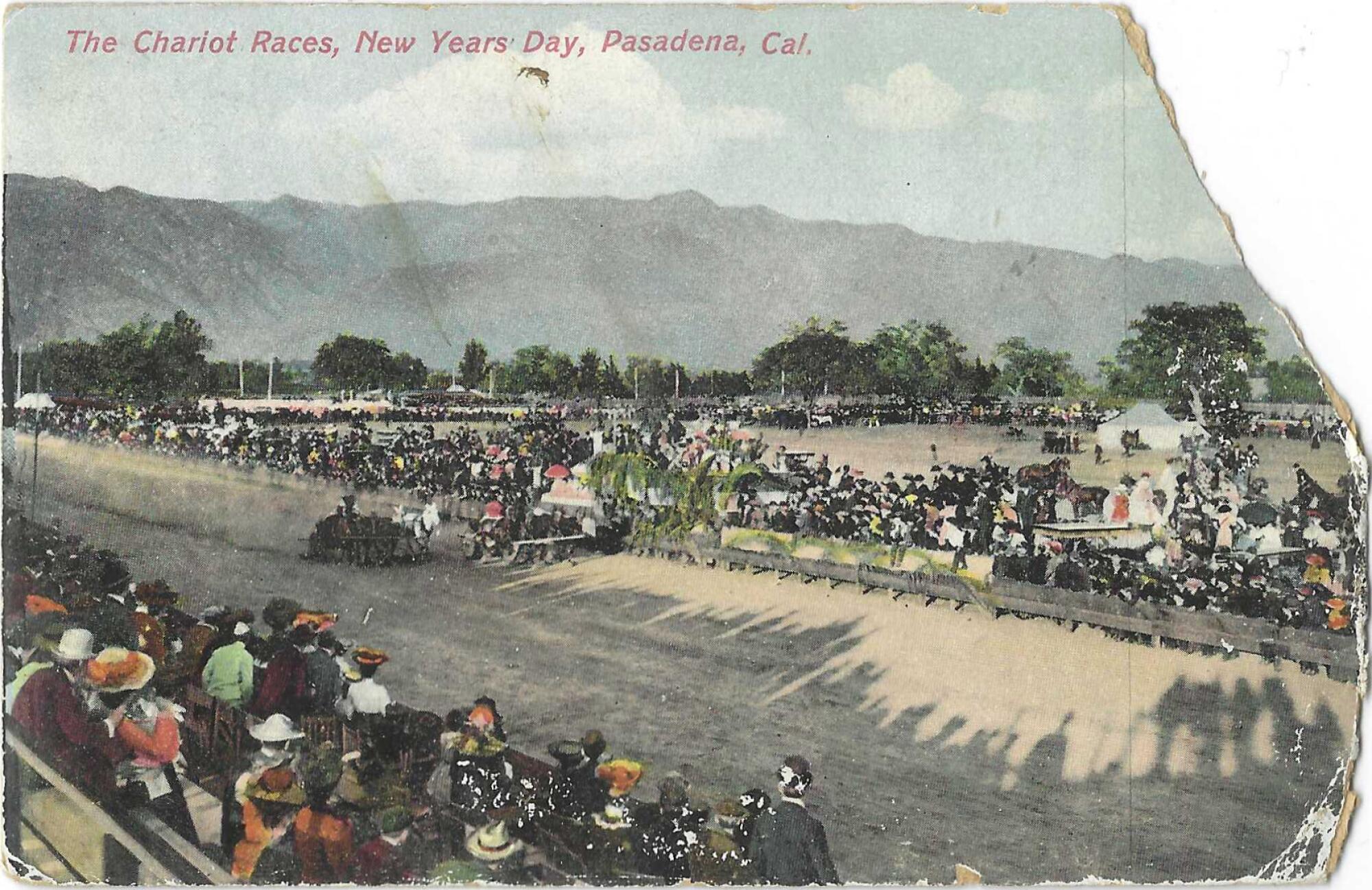

Colloquially, you are allowed to call it the Rose Parade, always capitalized. Although neither word is beyond the ordinary, together, they’ve created a Southern California PR bonanza and juggernaut since 1890, when the first decorously decorated carriages hit the midwinter streets of Pasadena.

From the few hundreds who stood curbside to watch the first parade, to those who saw it in black and white newspaper drawings, and then color photographs, and on television and now via the worldwide interwebs, it enticed uncounted hundreds of thousands to move to Southern California, and millions more glowering over their eggnog and under their thermal blankets at seeing the sun-swathed multitudes in shorts and T-shirts.

It’s not the Hollywood sign or the Eiffel Tower, but still, the thing got so visible and identifiable that it became a barometer and a template of the zeitgeist, and not always to its advantage. If this was America — even taking into account the chipper and the patriotic — then it was a pretty filtered vision of it.

Get the latest from Patt Morrison

Los Angeles is a complex place. Luckily, there's someone who can provide context, history and culture.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

During the mid-1960s, NAACP organizations threatened to picket and boycott parade events, and once, in 1967, Black people did picket the coronation of the Rose Queen with her all-white court. Miraculously, the very next year, for the 1969 parade, the all-white princessy spell was broken with the selection of Sylvia Peebles, a young Black Pasadena woman who said generously, “… it is nice to make history. It had to happen sometime.” And that same year, Janice Lowe became the first Asian American princess. “I am pleased to see the court represent America as it really is — a country made up of all people. This is particularly important since the tournament is so broadly publicized.”

Black leaders and groups sponsored the first Black float, “Freedom Bursts Forth,” for the 1964 parade, after a very public set-to over the parade’s absence of people of color. The parade chair’s rejoinder was that essentially he didn’t know what all the fuss had been about: “We’ve always had Negro participation. The majority of the bands have had Negroes in them. We’ve never had a policy on Negroes one way or the other.”

For some years, the parade had a prize category for religious organizations’ entries, and during the 1960s, the National Rifle Assn. sent out floats with names like “Land of the Free, Home of the Brave,” and “Bill of Rights.”

In 1991, the parade people stepped into a hornets’ nest of their own making when they chose a descendant of Christopher Columbus to be grand marshal for the 1992 parade, the 500th anniversary year of Columbus’ footfall in the New World. By 1991, there was already a pretty acute awareness about how catastrophic Columbus’ arrival and subsequent waves of European arrivals had been for Native populations in the Americas.

Yet the parade was taken aback by the ferocity and breadth of reaction to the choice, and in remarkably short order, there was what The Times called “an unprecedented capitulation to critics”: naming U.S. senator and Native American Ben Nighthorse Campbell as co-grand marshal. “Our goal,” explained the tournament president, “is to generate goodwill, not controversy.”

The 2023 grand marshal is former Arizona Democratic congresswoman Gabby Giffords, gravely wounded in a savage mass shooting in 2011 that also killed six people.

Forty or 50 years ago, it’s not likely she’d have been in the running for the star-seat ride in the big convertible. For many decades, a tally of the parade grand marshals shows a number of them to be Republicans or conservatives — not only the politicians but the entertainers, John Wayne, Bob Hope, Walt Disney, Jimmy Stewart, silent film pioneer Mary Pickford, and Frank Sinatra were grand marshals. Then, in the 1980s, the parade made grand marshals of liberal stars like Danny Kaye, who had once belonged to a Hollywood support group for the Hollywood 10, and the Oscar-winning actor Gregory Peck.

Four GOP presidents past, present and future were grand marshals — Richard Nixon appeared twice — as were a couple of California Republican governors, and two Republican-appointed Supreme Court jurists. As far as I can tell, the first Democratic politician to be grand marshal was senator and astronaut John Glenn.

Plenty of athletes made the cut: Amos Alonzo Stagg, Hank Aaron, Arnold Palmer, soccer legend Pele, Carl Lewis, and several Olympians. And military heroes — generals and Medal of Honor recipients — were prominent among the grand marshals.

The crowd favorites remain beyond politics: Vin Scully, Carol Burnett, Angela Lansbury, Charles Schulz, the Apollo 12 astronauts, Kermit the Frog, the heroic pilot Chesley B. “Sully” Sullenberger, and primatologist and anthropologist Jane Goodall.

Anything as old as this parade has accreted plenty of delish rumors. One, likely more truth than rumor, is why the parade never happens on Sunday. New Year’s Day in 1893 fell on a Sunday, and lest the hurly-burly frighten the horses at the churches along the route, it was put off until the next day. On the occasions that New Year’s Day falls on a Sunday, like Jan. 1. 2023, the parade rolls over by 24 hours.

Los Angeles used to hold the Fiesta de las Flores in the springtime, but the parade couldn’t stay fresh long enough to outlast Pasadena’s Rose Parade.

A sinister legend runs counter to the pious never-on-Sunday schedule: that early organizers made a deal with the devil to ensure rainless parade days. It has sometimes rained on the parade, and anyway, you have to wonder what the devil would have gotten out of it. (On the other hand ... National Weather Service forecast for Pasadena on Jan. 2, 2023, as of Dec. 27: “Mostly sunny, with a high near 60.”)

My favorite is the rumor that the choice of grand marshal, officially made by each year’s head of the Tournament of Roses, is, in fact, the preference of the chair’s spouse; either, or both, explains such wild swings as from actress Cloris Leachman one year to Sullenberger the next.

The parade’s arithmetic has been disputed by people as exalted as Caltech PhDs. Beginning in the 1930s, the party line from Pasadena police was that a million people were there watching the parade — sometimes as many as a million and a half. The Pasadena Star-News, in an act of bravura or lese majeste, challenged those angels-on-pinheads numbers, and referenced a 1960s story that three Caltech PhDs had figured the maximum number at 50,000. A 1971 transportation and engineering text bothered to calculate and came up with a max of about 891,000, and even at that would be an immobilized mass of people crammed into 1.5 square feet each.

On parade morning, it certainly must feel that way.

Explaining L.A. With Patt Morrison

Los Angeles is a complex place. In this weekly feature, Patt Morrison is explaining how it works, its history and its culture.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.