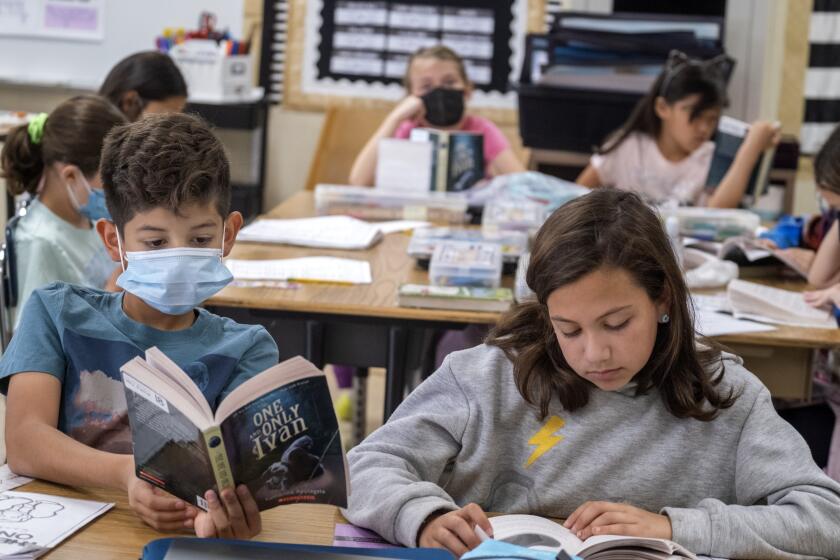

Only 1 in 9 Los Angeles students will attend extra learning days. What happened?

- Share via

A signature $123-million Los Angeles school district plan to help students struggling with pandemic-related learning setbacks by offering extra school days has failed to attract widespread participation, with about 1 in 9 students signing up.

The extra learning time — two days during winter break — was created as a back-up strategy after the teachers union pressured the school system to scrap a plan that would have made it harder for families to opt out.

A major challenge with the “acceleration days,” as the district calls them, is timing. Officials and school principals have to persuade families to come back after winter break has started — likely to an unfamiliar campus. The last day of classes is Dec. 16, a Friday. The acceleration days are the following Monday and Tuesday.

Given the small number of participants, the district extended the application deadline to Tuesday. But at Tuesday’s board meeting administrators said there would be no hard deadline and last-minute arrivals would not be turned away.

Test scores in Los Angeles Unified have shown troubling academic deficits in the wake of the pandemic and district officials have repeatedly urged parents to take advantage of the extra time with teachers, even if it falls during vacation rather than within an extended school year, as originally planned.

“We have pivoted,” Supt. Alberto Carvalho said. “This is the second-best alternative. ... Is it going to be perfect? No. Are we allowing the possibility of perfect to hinder our ability to deliver on something good? Absolutely not.”

The alarming dip in math proficiency and smaller declines in English in the last two pandemic-disrupted school years hit students who were already behind.

The endeavor is optional for students and school workers — who are paid for the extra work. Extra help still would be welcomed, said Andres Chait, chief of school operations, in response to questions from the Board of Education.

In all, more than 45,000 students had signed up by midday Tuesday — nearly 11% of the district’s 422,276 students. More than 8,000 of the district’s teachers and administrators have agreed to take part as well as more than 6,000 nonteaching employees such as bus drivers, supervision aides, cafeteria workers and custodians.

“Please send your child to school on those two days,” said newly appointed Chief Academic Officer Frances Baez. “It’s definitely a big yes — because it’s structured, it’s healthy, it’s safe. … They won’t regret it.”

But for many parents, there were too many questions and doubts.

“Parents were inundated with texts, emails and phone calls asking if their child would attend these days,” said parent Jenna Schwartz, the co-moderator of the Facebook site Parents Supporting Teachers. “However, no information was ever provided on what these days would look like, where they would take place, or who would be providing services. ... Many parents erroneously assume it will be at their school with their teacher.

“How much money was spent on the push for these days that will likely only serve 10%, at most, of the LAUSD students?”

North Hills parent Ariel Harman-Holmes said the program is a poor match for her children with special needs — she sees no benefit taking them to a new location with different instruction with no guarantee that elements of their specially approved individualized learning plan will be followed, such as her older son’s goal to master handwriting skills.

“If LAUSD thinks that this is some way to recoup learning loss, that’s not how to do it,” she said. “And it’s certainly not a way for special education kids. It’s like a hospital with people at different levels of triage just giving everyone the same Band-Aid on their finger. It doesn’t make sense.”

In central Los Angeles, Third Street Elementary parent Stephanie Hartnett said “it really came down to whether my son needed child care and if we thought he needed those extra two days of lessons.” The answer to both questions, she decided, was no. “He’s doing well in school and isn’t behind on any subjects.”

The district’s website has gradually answered more of the questions.

“There has been a lot of communication,” said school board member Nick Melvoin, “but [parents] don’t necessarily know what these days look like... This, I think, was one of the first public presentations we’ve done, but I’m hoping we’ll continue sharing that with parents.”

There’s also been some problem-solving in response to concerns. Officials decided to keep open special centers for students with disabilities. And if students have transportation on regular school days they’ll also have it on the acceleration days.

But there’s an exception. Some students ride the bus to a magnet school and many of these special academic programs will be closed. These students will have to attend a neighborhood school and get there without district transportation.

The setup will be a lot like a two-day summer school session. Not all schools will be open, but all students will have access to an assigned campus near their homes, Chait said. Students are likely to be with unfamiliar teachers and classmates, although teachers will have access to the test data of individual students on their roster and could adjust their instruction accordingly.

The day will be as long as a normal school day, although students will be assigned to one of two paths. Those behind grade level will receive small group instruction. Those doing better academically will focus more on enrichment — the district has prepared sample grade-level activities for teachers to use.

After-school programs will cover the same time span as during a regular school day at most but not all campuses.

In all, 293 schools — out of about 1,000 campuses districtwide — will be open, including all 100 “priority” schools identified because of low academic achievement or because they’re in a community with deep poverty, high crime or other issues.

At Tuesday’s presentation, administrators were not able to say whether the effort was reaching the students who most need help, although board member Jackie Goldberg estimated later that more than half of participants would fall into that category.

She noted an incentive for high school students who are failing classes: They would have an opportunity to do makeup work that could change their grade.

Districtwide, more than half of students are behind in what the state defines as grade level — and the pandemic made things worse. One-time COVID-19 relief aid is the source of funding for the estimated $123-million cost, which may come down because of low participation.

About half of the money went to pay teachers for training days before the school year started, said Carvalho. The rest was set aside for the acceleration days — the two in December and two more over the first two days of spring break. More recently, special training has been provided to more than 600 substitute teachers who will be taking part.

“We have an opportunity and a professional and moral responsibility to do all that we can to assist our students,” Carvalho said. “And this is one of many strategies that we are employing one that we cannot squander.”

Officials knew it would be a heavy lift to return students to school during vacation. Under the original plan, the extra learning days were on Wednesdays — resulting in a school year that was four days longer. The extra days were still optional for students and teachers, but set in the middle of a normal school week, it would likely be easier to attend them than avoid them.

2022 California test scores show 84% of Black students and 79% of Latino and low-income students did not meet state math standards.

But the leadership of United Teachers Los Angeles objected, saying the extension of the school year should have been brought to the bargaining table as a proposed change to working conditions. The union challenged the action with state regulators.

Rather than face a legal test and a threatened boycott by teachers, the district negotiated the current alternative plan.

Although the union accepted the compromise, its leaders also said funding would be better spent on strategies including “smaller class sizes, hiring more counselors, psychiatric social workers and school psychologists and investing in teacher development.”

The district also has invested in these strategies as well as individual and group tutoring — although these efforts were slow starting due to staffing shortages and incomplete planning.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.