- Share via

EUREKA, Calif. — Beauty drew Brieanne Mirjah D’Souza to Eureka.

In 2018, she and her husband — Michigan natives who had been living for a spell in the Bay Area — moved up to this chilly old timber town to build a life beneath the redwoods and by the sea.

But last winter, pregnant with her first child, D’Souza began reflecting on this pretty place she would bring her son into.

D’Souza, a 32-year-old digital marketer, is of Chinese and West Indian descent. And Humboldt County is very white.

As D’Souza’s belly grew and the headlines told of a dramatic surge in anti-Asian hate crimes amid the COVID-19 pandemic, D’Souza set out to find other people who looked like her.

A fledgling group started meeting over Zoom and trading emails. They learned there had once been a Chinatown in Eureka. Maybe they could commemorate it with a plaque, they figured.

But where had it gone?

::

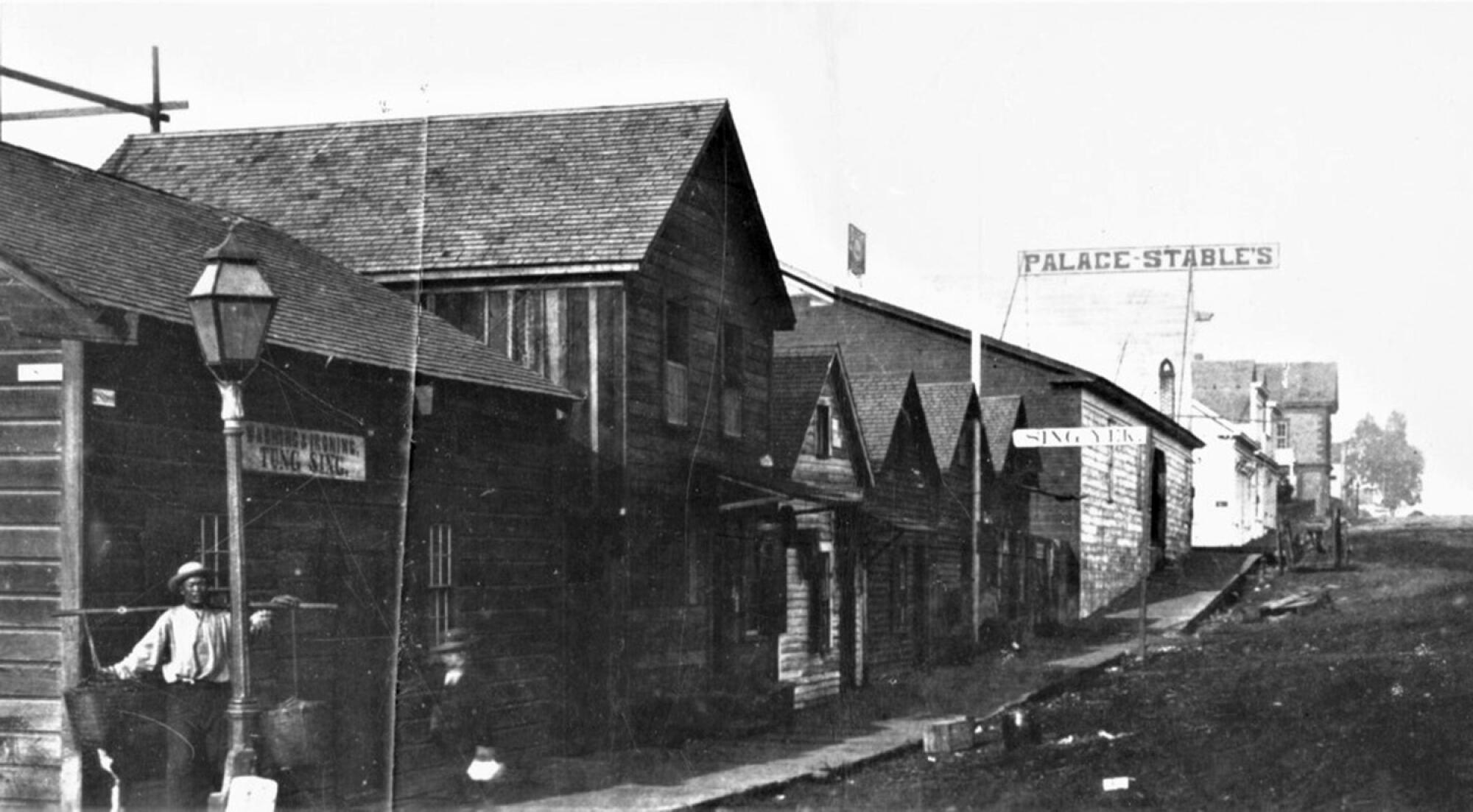

In the late 19th century, Chinatown occupied a single block in the middle of the remote, misty port town.

A few hundred Asian immigrants — mostly men — lived in Eureka after a federal law barred immigration from China in 1882.

They toiled in redwood logging camps, laundries and restaurants. They were nannies and household servants and vegetable growers. They were former gold prospectors priced out of the work because of a predatory state tax on foreign miners.

When the economy soured in the 1880s, white people blamed them, claiming they stole jobs. Newspapers whipped up anti-Chinese sentiment.

“There were a lot of stereotypes: that Chinese people were diseased, they were morally corrupt, they would not assimilate to the rest of American society at the time,” said Katie Buesch, a former director and curator at the Clarke Historical Museum in Eureka.

That sentiment was par for the course in the Golden State at the time.

Some California city officials are now acknowledging the ugly past — a counter-movement to red-state politicians pushing to ban books and limit the teaching of history that involves race.

Antioch and San Jose apologized last year for burning their Chinatowns in the late 1800s. San Francisco apologized for barring Chinese children from public schools.

Los Angeles is working on a memorial to commemorate an 1871 massacre in which at least 18 Chinese people were fatally shot or hanged. And in Pacific Grove earlier this year, organizers canceled a pageant that had long featured performers in yellowface.

In Humboldt County, Buesch, who had put together a small museum exhibit on Eureka’s Chinese community just before the pandemic, was struck by an 1885 article in the Daily Times-Telephone newspaper about Chinatown.

“The time has come when these plague spots should be removed,” the newspaper wrote.

On Feb. 5, 1885, the newspaper, which called the Chinese neighborhood a violent, drug-addled “leper’s colony,” wrote that it would probably be “goodbye to Chinatown” if an “unoffending white man” were killed there.

The very next day, a white Eureka city councilman who lived near Chinatown was walking past. Shots rang out between what is said to be two Chinese men, although details are scant. A stray bullet killed the councilman.

An angry mob of more than 600 white people — loggers, fishermen, miners and merchants — filled the streets, said Jean Pfaelzer, author of “Driven Out: The Forgotten War Against Chinese Americans.”

A gallows was erected. An effigy of a Chinese man swung from a noose.

Northern California city of Antioch apologizes to Chinese American community for how its early immigrants were treated.

Someone suggested slaughtering the Chinese, but that was deemed un-Christian, Pfaelzer said. Others said they should burn Chinatown, but its scrap wood buildings belonged to a white man, since the Chinese were not allowed to own property.

They instead appointed a committee of 15 men to go into Chinatown and order everyone to leave. The sheriff commissioned wagons to gather their belongings. Armed vigilantes roamed on horseback.

The next morning, about 300 Chinese people were marched to the wharf and eventually loaded onto two steamships: The Humboldt and The City of Chester.

They were shipped to San Francisco, where no one knew they were coming, Pfaelzer said. They disembarked and fled.

A few dozen sued the city of Eureka, but a judge tossed out their lawsuit.

The purge, which became known as the “Eureka method,” was copied in other towns across California and hailed by white people as nonviolent.

By 1890, the business directory for Humboldt County was boasting that it was “the only county in the state containing no Chinamen.” A Eureka law, in effect until the mid-20th century, banned Chinese people from working in the city.

::

In the spring of 2021, a gunman killed eight people, including six women of Asian descent, at three Atlanta-area spas.

The shootings sparked an outpouring of activism and calls to #StopAsianHate. They followed months of heightened attacks on Asian Americans amid a political climate in which then-President Trump was calling the coronavirus the “Chinese virus” and “kung flu.”

Around that time, D’Souza had set up an Instagram account she called APA Humboldt.

D’Souza quickly heard from a local group of Asian Americans who had organized a series of Japanese taiko drum performances before the pandemic.

They began meeting virtually. Their numbers grew. There was a real hunger for community in this county where only 3% of the population is Asian or Pacific Islander.

When a coveted ranch on the most pristine river in California was suddenly up for sale, a shocking history — and a massacre — bubbled to the surface.

The group delved into local history, poring through legal briefs, census data, letters, maps and journals to piece together the little-known story of Eureka’s Chinatown, which had been told mostly from a white perspective.

“We all had an awakening of sorts,” D’Souza said. “There was no awareness that there was once a thriving Chinese community here ... and they faced the same kind of discrimination and racism that we’re still facing today.”

D’Souza figured they would install a plaque before her baby came, and that would be that.

But what became known as the Eureka Chinatown Project — the work of the group now called Humboldt Asians & Pacific Islanders in Solidarity — blossomed.

With support from the city, they erected signs describing the expulsion in Historic Chinatown — which, today, is a downtown business district with banks, parking lots and no trace of the neighborhood that once stood.

There are plans for a monument.

And — with a mural and a renamed roadway — the Eureka Chinatown Project honored two local Chinese American pioneers whose legacies were too little known.

::

For seven decades, Eureka effectively kept Asians out. Until Ben Chin.

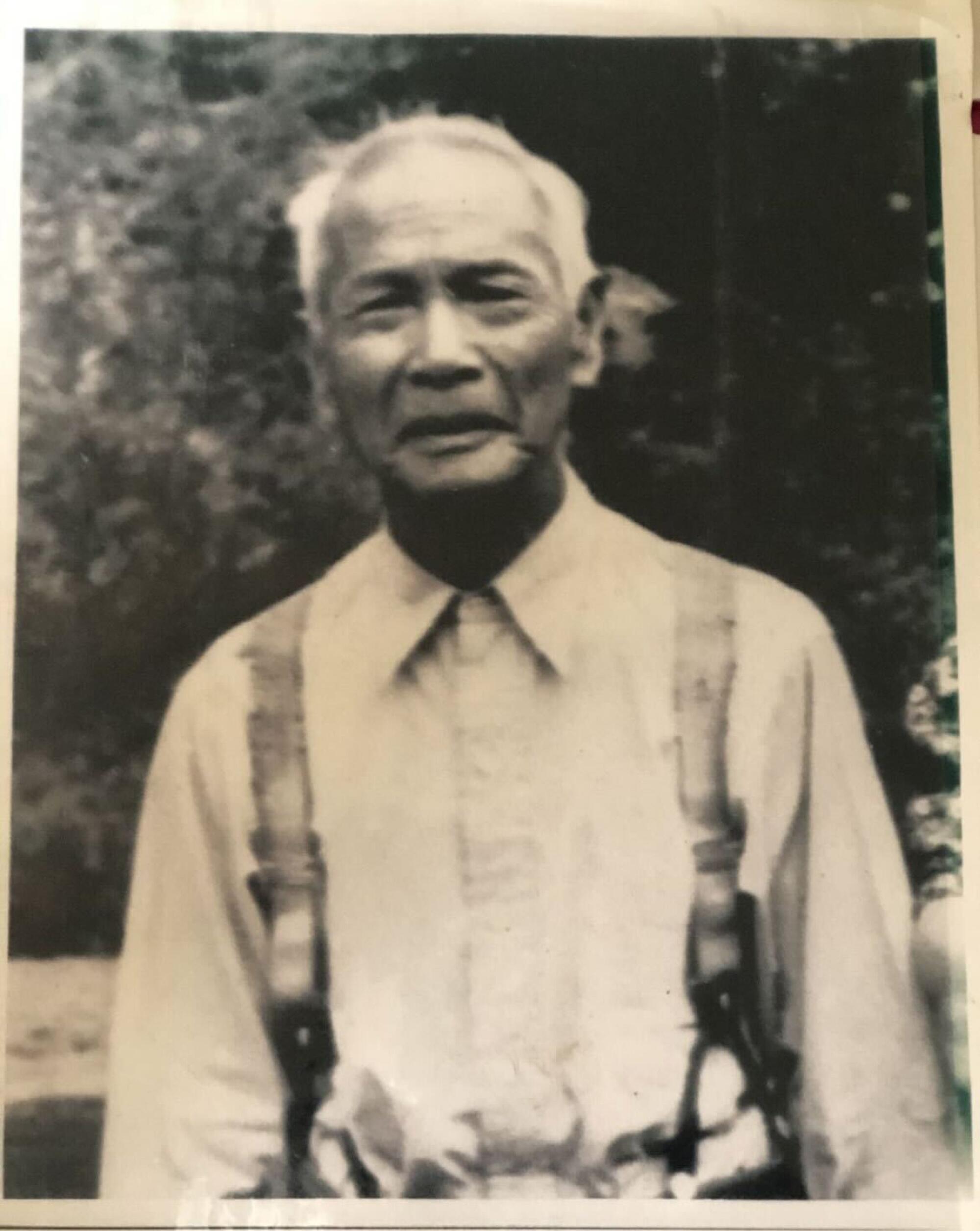

In 1954, he moved to Eureka to open the Canton Cafe. He was said to be the first Chinese person to put down roots in the city since the expulsion.

Chin was an immigrant from rural southern China who served as a U.S. military policeman during World War II in Germany, France, Italy and North Africa.

The mayor liked Chin — a generous man with a quick wit, a big laugh and a love of the San Francisco Giants — and became a regular patron. But the city did not want too many Chinese people in town. So Chin was allowed to hire only one cook at a time.

Racist callers threatened him at work: “Get out of town!” “We don’t want Chinamen here!”

Chin stood 5 feet 3, but he was military buff and could pull off an intimidating scowl when he needed to, said Mary Chin, his wife of 57 years, who still lives in Eureka.

“If you want to tell me something, come in person,” Mary, 83, recalled him telling callers. They never did.

“I don’t think you want to mess with a guy who knows how to use a meat cleaver,” his son, Don Chin, a Eureka realtor, said with a laugh.

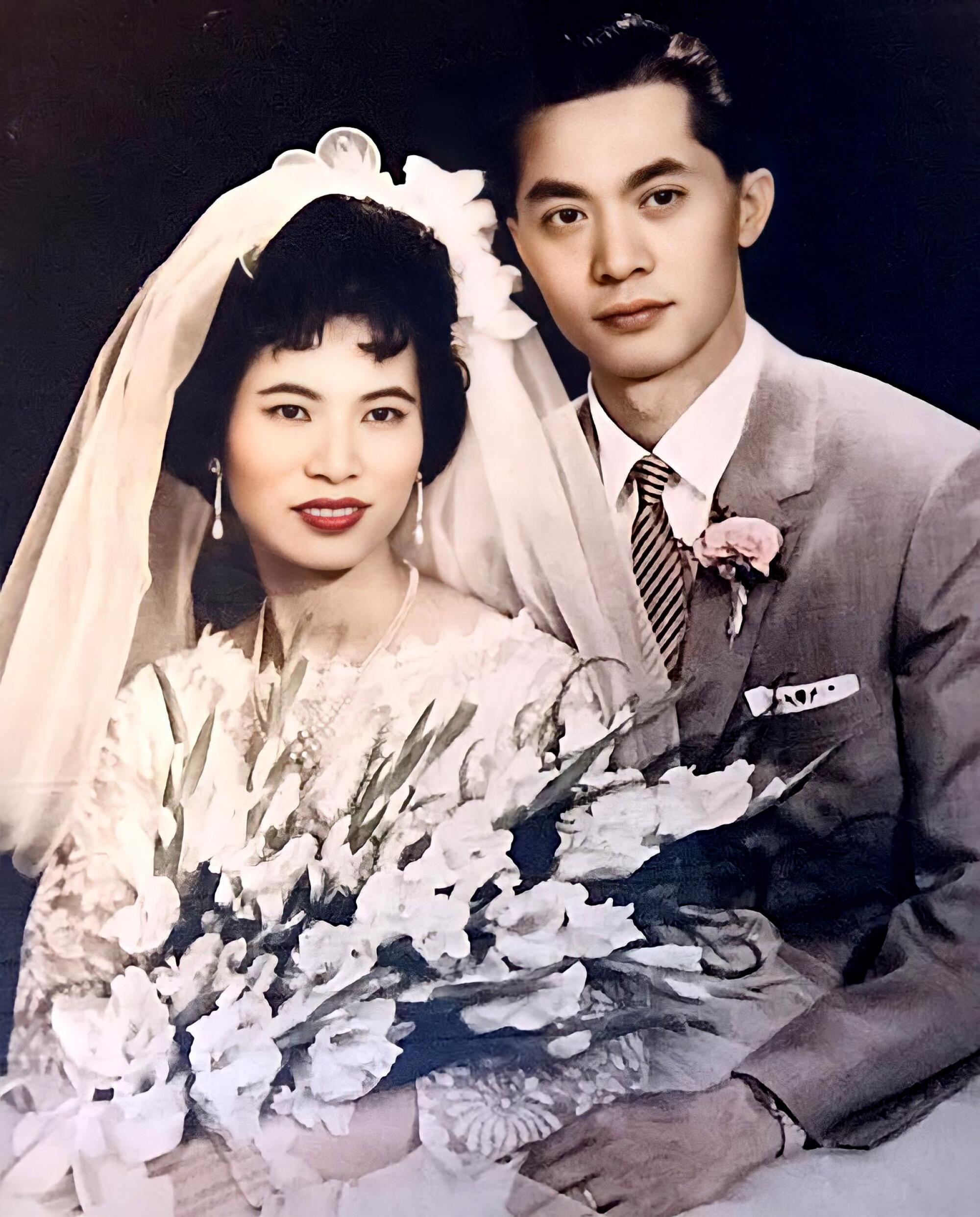

Mary met Ben, who was 17 years her senior, in 1962, when he came to Hong Kong looking for a wife.

The daughter of poor farmers, she had lived in Hong Kong for a few years after fleeing China by boat.

Her aunt introduced her to Ben, and a few weeks later they wed. She spoke no English when she moved to nearly all-white Eureka and, for years, rarely went anywhere besides the restaurant.

In an interview with her son Don and his half-brother, Ben Chin Jr., she said that even as the hateful calls came in, “I wasn’t afraid because your daddy was there.”

The Chins singlehandedly grew Eureka’s Chinese population, between their employees, the family members they brought to the U.S. and their children, who grew up washing dishes, waiting tables and cooking in their restaurants.

Ben Chin died in 2019 at age 97.

On a recent, misty afternoon, Mary stopped by the mural honoring her late husband, commissioned by the Eureka Chinatown Project last year in Historic Chinatown.

It is called “Fowl” — a play on the word “foul,” which was so often used to disparage the community — and has an image of a mandarin duck, which represents love and fidelity in China.

It includes a portrait of Ben Chin in his military uniform.

“My young man,” she said with a sad smile. “When I miss him, I come here.”

::

The mural is along an alleyway that the city, at the urging of the Eureka Chinatown Project, renamed last year: Charlie Moon Way.

At the time of the 1885 purge, Moon worked as a cook and manual laborer on a ranch on Redwood Creek. When armed men came to drive him out with the rest of the Chinese, his boss pulled out a gun and refused to surrender him.

Moon was long said to be the last Chinese person in Humboldt County — a falsehood, as a few Chinese men lived in very remote, rural parts.

Moon married a native Chilula woman, the daughter of a blind medicine man, and they had eight children. They stayed put.

“History always wants to romanticize it. But when you go back to that time and place, I don’t see anything romantic about it,” said Yolanda Latham, Moon’s great-great granddaughter, who still lives in the area. “For my family, we’ve always had a lot of trauma.”

Life was hard in this county where, 25 years before the Chinese expulsion, a group of white settlers bearing knives and hatchets rowed across Humboldt Bay to Tuluwat Island and murdered some 80 to 250 Wiyot people — mostly women, children and older men — as they slept.

The Moons were “written off as half-breeds,” despised for both sides of their heritage, she said.

The Eureka Chinatown Project inspired Latham to look more into the history of “Grandpa Charlie.” She is thrilled that future generations will know his name — and the truth about the region’s ugly, violent history.

“The mural is healing, the signs are healing,” she said. “Charlie Moon Way gives us a sense of pride and place. We were here. And that was our grandfather.”

“I think the past was so painful that no one wanted to remember,” she added.

::

Volunteers for the Eureka Chinatown Project, who represent a diversity of Asian backgrounds, including Japanese American women whose parents were incarcerated in U.S. prison camps during World War II, now give walking tours of the old Chinatown.

The tours always run long. People want to stay and process what they’ve learned.

D’Souza’s son, Silas, entered the world last summer. He was one of three “Chinatown babies” born to volunteers.

“As he walks down the street as he grows up, I want him to see his culture in the artwork that’s on the walls and the statues and monuments that are implanted on the ground,” she said.

“I want him to have that sense of belonging.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.