Dolores Huerta’s passion for music will be illuminated at CSUN tribute to civil rights activist

- Share via

Dolores Huerta’s personal playlist contains a medley of historic sound bites. Fiery speeches from San Joaquin vineyards. Fervent chants of “¡Si, si se puede!” Ronald Reagan ostentatiously chomping on grapes in defiance of what he deemed the “immoral” farmworkers strike that Huerta championed alongside Cesar Chavez.

But the audio archive of Huerta’s mind keeps several other tracks in heavy rotation. Stravinsky’s “Firebird” suite. Billie Holliday’s “God Bless the Child.” John Lennon’s “Imagine.” Not to mention cumbias, mariachi and flamenco. Boleros from the borderlands, civil rights gospel anthems and Dust Bowl dirges.

“I always say that art touches the heart and the mind and the soul,” Huerta said over dinner last week at a Thai restaurant in Bakersfield, minutes after delivering a pre-election rally-the-faithful speech at Cal State Bakersfield. “It gives you the consciousness that you need and the healing that you need and the energy that you need. Music and art and drama do all of those things.”

Huerta was in the city she ironically and affectionately refers to as “Bakersfield, Alabama,” to give a lecture on “How to Overcome Apathy and Find Your Power.” She’d flown in that night from campaigning in Nevada with John Legend, Elizabeth Warren and Barack Obama. The next day she’d fly to Georgia to campaign with Stacey Abrams, then on to Michigan to canvass voters ahead of last Tuesday’s elections.

This Sunday she’ll be the honoree at a musical tribute, “Concierto Para Dolores,” at CSUN’s Soraya performing arts center, hosted by actor, comedian and writer Cristela Alonzo, with musical direction by Cheche Alara and performances by La Santa Cecilia, John Doe, Gaby Moreno, Marilyn McCoo and Billy Davis Jr. and David Aguilar, among others.

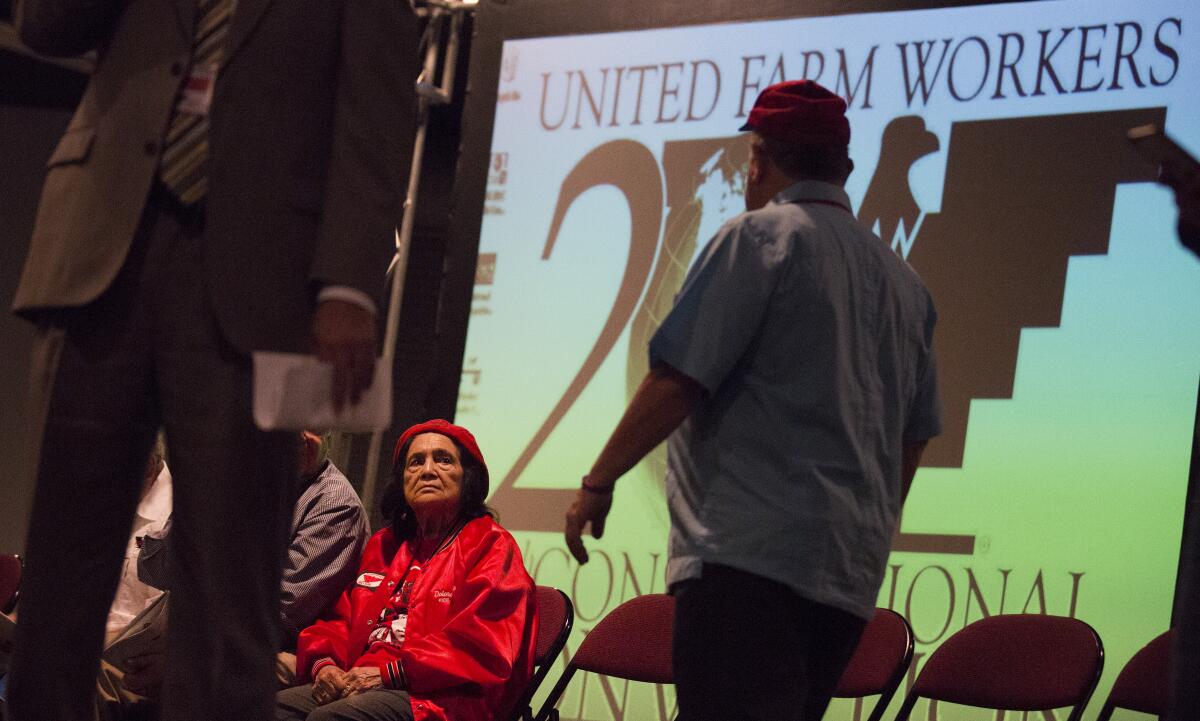

She is 92. She has raised 11 children. She has been an activist since high school. Her 5-foot-2-inch body suffered a ruptured spleen and fractured ribs when police clashed with demonstrators in San Francisco in 1988. She has had COVID twice.

“And, trust me, you cannot keep up with that woman,” said her longtime friend Dan Guerrero, who will direct Sunday’s show. “Atomic woman is what she is.”

These days Huerta’s legacy as a labor organizer is known to practically anyone with a cellphone and a social conscience. Less familiar is her reverence for the arts and their transformative capacity, an intimate side of her that the concert will seek to illuminate and animate.

Huerta’s lifelong romance with music, dance, visual art and theater began when she was a child learning violin and tap dance, and singing in two choirs at two churches. A cousin introduced her to Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie records.

And Cesar? “He was more of a Benny Goodman guy than a Charlie Parker guy,” Huerta said with a smile.

It’s tempting to think that jazz is her favorite musical form because of its affinity with political activism. You can’t riff unless you’re sure of the core melody. Improvise all you like, but stay true to the beat.

On the road, where she spends much of her time, Huerta often takes in shows and concerts, and “if there’s live music, the woman’s going to dance,” Alonzo said. “I could tell you stories of her and I dancing to A Tribe Called Quest.”

Guerrero, 82, said that Huerta and he came of age at a moment when politics and art shared a pillow. His father, Lalo Guerrero, the activist and father of Chicano music, wrote “El Corrido de Delano,” one of the first songs about the farmworkers movement. Visual artists like Barbara Carrasco and Carlos Almaraz were supporting el movimiento while revolutionizing how Latinos viewed themselves. Luis Valdez’s Teatro Campesino was turning farmworkers into accomplished actors.

Several of Sunday’s performers and presenters didn’t learn that history until later in life. But the example of Huerta and her colleagues now helps drive their own art and actions.

“Our school district was like 99% Latino, yet we weren’t learning about Latinos in history. We were learning the classic ‘Columbus came over and blah, blah, blah,’ ” said Alonzo, who grew up in south Texas. “So when I bumped into a piece about Dolores, I thought it was so cool that there was another Mexican American woman that had done enough that people were writing about her.”

Singers McCoo and Davis recalled being swept up in the tumultuous 1960s, like Huerta, as members of the 5th Dimension when they were caught in the middle of the head-cracking melee that broke out at the 1968 Chicago Democratic convention. On Sunday, Davis will sing “Blackbird,” the Beatles’ nod to the Black women of the civil rights era.

“The lyric today is as powerful as it was then. It’s talking about how we’ve got to come together,” McCoo said.

Davis will also interpret Marvin Gaye’s soul classic “What’s Going On,” which he suggests could’ve as easily been written in 2021 as in 1971.

“There’s always been problems and protests in this country, and the police brutality, and it seems like they just can’t keep their hands off the brothers,” Davis said.

Growing up in Guatemala, singer-songwriter Moreno hadn’t heard of Huerta and Chavez until she moved to Los Angeles in the early 2000s. She compares Huerta to Guatemalan feminist and human rights activists like Helen Mack Chang and Rigoberta Menchú, the latter the K’iche’ Nobel Peace Prize laureate. Those women, and socially conscious Latin American trova singers like Cuba’s Silvio Rodríguez and Violeta Parra and Víctor Jara of Chile, have colored Moreno’s burning musical entreaties on behalf of immigrants and other causes.

“There’s something that I read recently that Dolores said in an interview, that everyone needs to be an activist,” said Moreno, speaking by Zoom while touring in Germany. “I firmly believe that. Even as musicians, I feel like we have that responsibility to speak out on any subject that is affecting not just yourself but the world.”

La Marisoul, the brilliantly attired lead singer of La Santa Cecilia, said that she feels “like Cesar Chavez’s and Dolores Huerta’s names have been around my ears all my life. I don’t know if it was growing up on Olvera Street or the marches that would pass by, or people passing pamphlets, or when Cesar Chavez visited Olvera Street, maybe in the ‘80s.”

She credits Huerta’s generation of activists and artists with encouraging La Santa Cecilia to tackle subjects like the way harsh policies shadow immigrants’ lives, in the band’s 2013 punning protest tune “El Hielo (ICE).”

“What I love about her is that when you hang out with her, she’s a joyous, happy, like a true lover of life,” La Marisoul says of Huerta. “Una luz, una fuerza. I don’t know if she knows how important her light and her fire is to all of us. But I think it’s an honor to be able to celebrate her on this evening.”

Whatever music she hears every day, Huerta wants all of us to hear it too. Like the way the opening clarinet solo of “Rhapsody in Blue” sprang to mind one early morning in New York City, where she and farmworkers had gone to rally at the Hunt Point Market in the Bronx.

“The city is so quiet then, and the beginning of the ‘Rhapsody in Blue’ reminds me of that. And then when we were coming back, like at 7 o’clock in the morning, the cars were honking, like the percussion.”

Even Huerta doesn’t know the full program for Sunday. Show director Guerrero has promised some surprises.

But this much can be said with certainty: If there’s music, the woman’s going to dance.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.