Luna is running for Los Angeles County sheriff as the anti-Villanueva. Will it work?

- Share via

Robert Luna likes to point out that he’s held every rank in the Long Beach Police Department since he joined as a reserve officer in 1985.

Under his watch as the department’s first Latino chief — a seven-year stint that ended when he retired in December — property and violent crimes in the city fell, although the annual tally of homicides and rapes increased.

Luna is proud of his record in Long Beach, but there’s one problem: It’s barely known beyond the boundaries of the second-largest city in Los Angeles County.

He’s running to unseat embattled Sheriff Alex Villanueva, who commandeers local and national headlines whether he likes it or not. But a recent poll found that more than half of likely voters had no opinion of Luna. In the world of political polling, that often means they don’t know who he is.

As election day nears, getting his name and message in front of voters is key for the affable 56-year-old, who is pitching himself as the cool-headed antidote to years of Villanueva scandals and fear-mongering.

As one L.A. political observer characterized the situation, the current sheriff does better every day he dominates the headlines, positive or negative; Luna’s task is to find a way to cut through the noise.

That’s particularly true, given poll results published earlier this month showing 36% of likely voters still hadn’t decided whom they will vote for — the same percentage that planned to vote for Luna; 26% said they’re voting for Villanueva.

It’s all in keeping with a prediction Luna says he made before he entered the race for sheriff last year.

“I looked at the field of people that were running and I said, ‘I can beat this guy,’” he said. His success in the primary, Luna said, proved that “everything we did worked. Our strategy worked. Our messaging worked.”

Los Angeles County Sheriff Alex Villanueva is in a tight race to keep his job, with retired Long Beach Police Chief Robert Luna emerging as the front-runner.

At La Imperial Tortilleria & Restaurant in East Los Angeles on Sept. 29, Luna spoke for about half an hour to prospective voters in a busy dining room decorated with colorful falsa blankets and sombreros and black-and-white photographs of Frida Kahlo.

He gave the abridged version of his regular stump speech — “56 years of my life in about 10 minutes” — fine-tuned to appeal to the gathering of mostly Mexican American business owners. He expounded on his local roots and his vision for the Sheriff’s Department. (Reform the agency. Reduce violent crime. Address homelessness.) He also shared some of his many criticisms of Villanueva.

But at root Luna is posing himself as a more even-keeled alternative to the sheriff’s bluster, as a way to rebuild trust in a broken system, as a stabilizing force.

“I don’t make campaign promises, but I will promise you this: I won’t forget where I came from,” he said. “I’m a person who cares, I’m a person who wants to make a difference. … Or I’m going to die trying, giving it my all for Los Angeles County.”

Born in an East L.A. hospital, Luna grew up in the neighborhood, which is served by the Sheriff’s Department. As a young boy, he saw violence and police beatings on the streets outside the one-bedroom apartment on East 5th Street where he and his sister shared a bunk bed. He still recalls a gang fight that spilled over into their yard.

Luna was the oldest of three children, the first in his family to graduate from high school and college. His father worked as a school janitor. His mother harvested nopales from their neighborhood’s low-lying hills, painstakingly dethorned them by hand and sold them to neighbors, along with homemade tamales.

Deeply proud of his upbringing and his family’s roots in Sinaloa and Michoacán, Luna straddles a fine line.

read more coverage

Here’s who has raised the most money for Villanueva and Luna, and where it’s coming from, for the 2022 sheriff’s election

He is from a community that he recalls as predominantly anti-police when he was growing up. At age 13, he said, he was slammed face-first against the hood of a sheriff’s deputy’s car for crossing against a red light on his bicycle in Santa Fe Springs, where Luna’s family bought a house and he attended middle and high school.

Yet he has wanted to don a uniform and badge since he was very young. When a deputy talked to his class in first or second grade, Luna said, he was “mesmerized by the uniform, the star on his chest, the gun belt, the gun. And that was the first time that it was, like, that feeling inside of, ‘You know what? I want to do that.’”

Luna fulfilled that dream when he graduated from the Long Beach police academy.

“He’s had this passion since he was 5 years old. He and his sister, they used to play cops and robbers, and he was always the cop,” Luna’s wife, Celines, said outside a cavernous local taqueria called East Los Tacos before her husband’s campaign stop there late last month. “It’s what he breathes, sleeps, eats.”

Late last summer, after 36 years at the Long Beach Police Department, Luna sat his family down across from the fireplace in their living room on the city’s east side and told them he planned to retire from the department and run for sheriff.

Celines said she and their two adult children were immediately supportive. They became his first campaign workers; Celines stuffed and licked envelopes, their son handled social media, and their daughter did graphic design.

Luna quickly built support among Long Beach business owners and Mexican American residents who saw something of themselves reflected in the self-made leader from a rough part of East L.A. Barely six months later, he notched a surprisingly close second-place finish to Villanueva in the June primary.

“I’m cautiously optimistic, but I’m humbled by the support,” Luna told The Times as he stood near his blue-lighted swimming pool during a small gathering as early returns came in that evening.

Luna has since been endorsed by all seven candidates he bested in the primary. His showing was so convincing he is seen by some political watchers as the presumptive sheriff.

Still, three days after the primary, LAist ran a story asking a question on many Angelenos’ minds: “Who the Heck Is Robert Luna?”

As a first-time political candidate running against a bombastic sitting sheriff — who’s a fixture on Fox News and has been at the epicenter of a succession of prominent scandals — it’s inevitable Luna will have less name recognition.

Luna folds his tall frame into a rented car most mornings to drive to yet another meet-and-greet or community event. He has shaken thousands of hands while campaigning in every crevice of L.A. County. But many people know Luna more as the anti-Villanueva than for his specific platform and qualifications.

That relative anonymity can be a strength when he’s pitching himself to people fed up with what they see as the high-profile bullying and paranoia that have defined the Sheriff’s Department over the last four years. But some voters wonder whether Luna has the conviction and integrity to take unpopular stands. And several former Long Beach officers have voiced concerns about how he ran that department.

“I get a feeling that Luna’s going to be sheriff,” East L.A. shopkeeper Ed Garcia said after watching Luna speak at La Imperial last month. “But I don’t know if he would have the guts to stand up and do what he thinks is right even if it’s not popular, and that’s what Villanueva’s done that’s so good.”

On the street, in the dining room of a family restaurant, or mic in hand on a makeshift stage at a community meeting hall, Luna presents a calm and disciplined, if somewhat folksy, image.

A longtime Republican, he changed his registration to no party preference only in 2018 and became a Democrat two years later. Often greeted as “chief” more than nine months after he retired, Luna fills his loose-fitting navy blue suits with an air of authority and aptitude.

Long Beach Mayor Robert Garcia was in office the entire time Luna was chief. Luna, the mayor said, has the demeanor and experience needed to take the reins of a department in crisis.

“The chaos around the current sheriff needs to end, and there’s no one better suited to that than Robert Luna,” Garcia said. “He’s calm, collaborative, collected ... and his integrity and always trying to do the right thing always took center stage.”

The former chief also has a knack for quickly connecting with people and making an impression by sharing details of his life and focusing on common experiences.

Late last month, as Luna stood in the heart of an East L.A. commercial district, two longtime residents hanging out on the corner of Whittier Boulevard and McDonnell Avenue started a conversation with him about their neighborhood. One of the men held a can of beer as he discussed the gangs that have operated there for decades, including the Little Valley crew, which claimed Luna’s block as part of their turf when he was a child and once counted some of his kin among its members.

“Did you happen to know a guy named Salvador?” Luna asked the men. “He was shot and killed in Little Valley. He was my uncle.”

At Ruben Salazar Park, about a mile and a half to the west, Luna switched to Spanish as he spoke with a group of older Mexican American men and women who were gathered to share gossip and a laugh over boisterous hands of conquian. Luna asked about their families and their lives and told them about his own.

“My name is Robert Luna and I’m running for sheriff,” he told them. “I went to Rowan Elementary. … I went to the pool here in this park.”

Maria Gonzalez said she was impressed by her brief chat with the candidate that day.

“It does make a difference when you have someone who’s lived here, because you have shared experiences,” she told him in Spanish. “You’re not from Beverly Hills. You understand what families go through who live here.”

Like Villanueva in 2018, Luna pitches himself as a reformer and a man of the people. But also like Villanueva, his career has been more complicated than that.

He was criticized in 2020 after his officers were “overwhelmed” — as The Times put it at the time — by the scale of the unrest in Long Beach after George Floyd was murdered by a Minneapolis police officer.

Luna was on the executive board of the Major Cities Chiefs Assn., which advocates for law enforcement interests at the national level. In that capacity, he worked with the White House, members of Congress and Cabinet members, according to Laura Cooper, the group’s executive director, who said she was impressed by Luna’s poise in the wake of Floyd’s death.

“He was an executive board member at the height of our conversations about police reform, and he is a very pragmatic and open-minded person,” Cooper said. “And given the tenor and heat of those conversations, it was great to have him be a part of that because he was a very measured and thoughtful voice.”

In what was perhaps an inevitable occurrence in a high-profile countywide race against one of the most divisive politicians in recent local memory, Luna is now on the receiving end of a full-court press by Villanueva and his campaign staff to sully his image before November.

The Villanueva campaign has connected The Times with several former Long Beach police officers who said they were mistreated, sidelined and even fired because of alleged racial bias in the department while Luna was chief and long before he was in charge.

For years, a long list of allegations against the Police Department has been chronicled in detail by the Beachcomber, a Long Beach newspaper that has consistently called Luna to task for his missteps as chief.

In an interview last month, Mark McGuire, a Black former Long Beach police officer and homicide detective, alleged there were only “30 to 40” Black officers out of more than 700 in the Long Beach Police Department throughout much of Luna’s tenure as chief. More than 12% of Long Beach residents are Black.

Luna said in an interview that, when it came to the diversity of the department, “as the chief of police I was never happy with the numbers we had.” He said that as of Jan. 1, just 6% of the department’s officers were Black, while 43% were Latino and 11% were of Asian descent.

But, Luna said, he did promote numerous people of color to higher-level civilian and sworn positions. When he became chief, none of the department’s 12 commanders were Black, Luna noted, and when he retired in December, three were. Although he hired diverse academy classes as chief, he said, his ability to promote lower-ranking members of the department was greatly restricted by city policies that base such promotions on civil service test scores.

“The goal is to hire and promote the best talent possible. And within that you do everything you can to diversify that group,” he said. “We’ve come a long way. … But we still need to go further.”

According to Kevin Lee, a spokesman for the city, current data show that of 759 Long Beach officers, 35 — or 4.6% — are Black.

In a recent interview over iced tea in a Torrance shopping center, Quincy Miles, another Black former Long Beach officer, echoed McGuire’s concerns about diversity in the department. Both alleged that officers were systematically sidelined and fired for formally reporting discrimination.

“Every Black officer who had filed a complaint alleging racial bias has been terminated,” Miles said.

Luna denied the claim that people were fired for reporting racial bias, stating that “although we looked for it, I never saw any evidence of that, and we took those allegations very seriously. If anybody was claiming retaliation of any kind, that would be investigated.”

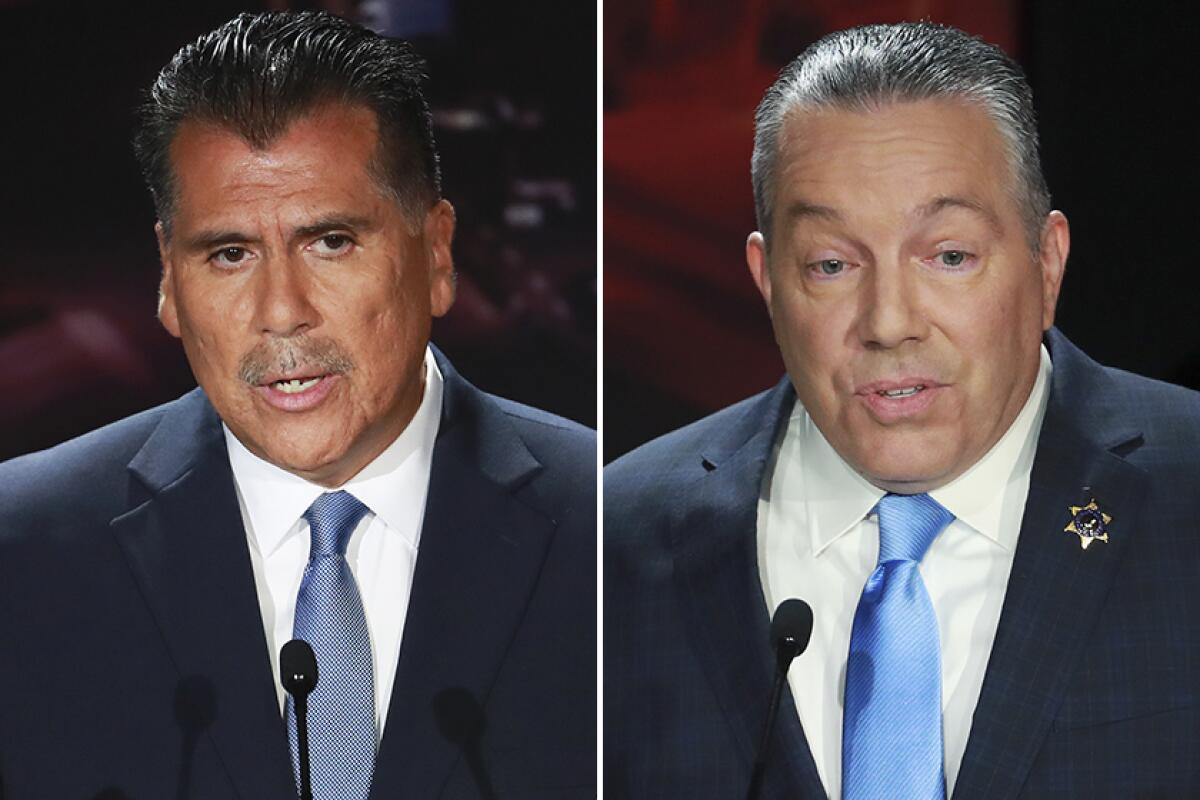

Villanueva voiced similar claims about Luna’s tenure in Long Beach during a televised debate between the two candidates last month. He also alleged Luna failed to properly respond to racially charged incidents, including the discovery of a noose drawn on a poster in the department’s homicide unit before he was chief.

“When people came to Mr. Luna as a supervisor to complain about it, they’re the one[s] that faced the retaliation,” Villanueva said. Luna said he reported the noose illustration incident, and it was investigated.

“There’s a lot of mistrust,” Luna said moments later. “For me, being elected as your sheriff, I’m going to work my tail off to do everything I can to work with all communities — specifically our Black community — [to] make our relationship better and unique.”

Times data and graphics reporter Katie Licari contributed data analysis to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.